Although the COVID-19 pandemic and economic difficulties have limited funds available for technical modernisation, Southeast Asian states are striving to meet their priorities, among which Naval modernisation remains a key goal.

Development and security of all states in Southeast Asia depend on their unhindered access to seas. No wonder that they most of them consider a maritime security as a priority. Their naval forces have to tackle with numerous threats, such as terrorism, smuggling, human and drug trafficking as well as piracy. Vital problems also include the rise of armed robberies and kidnappings. Another factor increasing the demand for naval procurement is the age and obsolescence of much of the equipment in service.

The modern maritime environment poses a wide range of challenges, many of them non-conventional threats, however this does not mean that traditional threats have gone away. Regional naval forces must be ready to protect natural resources from other state actors. In this vein, all leading navies in the region have decided to hedge against risks posed by China’s rise and expansionist policy. Even states with otherwise warm relations with China, such as Malaysia, have decided to boost their naval deterrence. Due to a myriad of possible challenges, Southeast Asian fleets have to develop and maintain a wide array of capabilities for various peacetime and potential conflict scenarios.

Indonesia

Indonesia has an ambition to establish a fleet, mainly for green water operations, composed of 274 ships, divided into three categories: 110 combat/strike warships, 66 patrol vessels and 98 auxiliary units. Such numbers are required if Jakarta wants to be capable of protecting its EEZ and thousands of islets, especially given Chinese territorial claims run through Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea. It is also crucial to materialise Jakarta’s growing ambition within Indo-Pacific.

Jakarta wants to spend USD 125 billion on modernisation of all military branches until 2044, which will require borrowing. When it comes to the Indonesian Navy, the pace of modernisation is insufficient – 50 warships of various classes and types were expected by 2024, but in approximately the last couple of decades Jakarta has introduced only three submarines, two frigates, and seven corvettes into service. As noted by Ristian Atriandi Supriyanto (CSIS’s Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative), “If it has taken Indonesia more than a decade to realize this posture, then it is even less likely to bridge the shortfall within the next 24 months”.

Indonesia’s ambitions were underscored when Jakarta recently requested additional three 1,270 tonne CHANG BOGO class/NAGAPASA class (Type 209/1400) submarines from South Korea. Thanks to that deal, the Indonesian Navy would have 7 submarines (including one Type 209/1300/Cakra class). However, this deal has been facing serious problems – Jakarta refused to make a down payment (10% of the total contract value) and is reportedly considering cancelling the deal. According to the Asia Times newspaper, “Indonesia is reportedly not satisfied with the capabilities of the vessels, citing power supply problems connected to batteries among other issues”. As such, other options are being considered.

Jakarta wants to have at least 10 operational submarines, and the Navy would like to increase that number to 12. To meet these goals, Indonesia wants to buy two SCORPENE class submarines from France (already in service in India and Malaysia). Reportedly four vessels of that class might be procured over the longer term, most likely replacing the CAKRA class submarines. For now, Indonesia has only three modern submarines, their NAGAPASA class vessels. In support of their submarines, last year, Indonesia started the construction of a submarine support station on Natuna Island in the South China Sea.

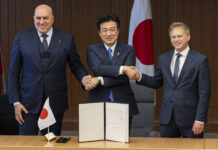

In terms of surface vessels, Japan is to deliver up to eight MOGAMI class frigates, four of which would be built locally by PT PAL. The same Indonesian company will be involved in providing local modifications for two ARROWHEAD 140 frigates on order, which are to be built by Babcock following a contract award in April 2020. Jakarta has also ordered six Italian BERGAMINI class (FREMM) frigates and two refurbished MAESTRALE class corvettes, the latter of which will be modernised by Fincantieri.

The latest order was made in January 2022, when the Indonesian Navy announced that South Korea would donate a retired corvette, most likely a POHANG class, given that three were retired in December 2021. The transfer of additional two corvettes is under consideration, and is also considered likely as, despite some disagreements, Seoul maintains strong ties with Jakarta and additional deliveries would strengthen them further. These ships would be useful in securing Indonesian waters, including the Natuna Regency, the northernmost islands in the Riau Archipelago.

In September 2021 PT Daya Radar Utama Shipyards launched the construction of two Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs), with one being 60 m long, and the other being 90 m long and armed with up to eight anti-ship missiles. In early 2022 Indonesia commissioned the DR WAHIDIN SUDIROHUSODO (991) hospital ship and the GOLOK (688) trimaran-shaped KLEWANG class fast attack craft. The first of the class, KLEWANG, was destroyed by fire soon after its launch in 2012.

The Philippines

At present, the Philippines cannot rule out the possibility of conflict with China. Radio Free Asia reported that “in 2021, the Philippines faced blowback from China as Manila repeatedly protested against the presence of hundreds of fishing boats believed to be manned by Chinese militias within Manila’s exclusive economic zone”. This country initiated a major upgrade of its aging navy more than a decade ago, but financial constraints, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, forced Manila to limit its ambitions. Nevertheless, the Philippines successfully acquired new frigates from Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), which were based on a modified INCHEON class design with an eight-cell Vertical Launch System (VLS). The first ship, JOSE RIZAL (150), was commissioned two years ago, while the second ship, ANTONIO LUNA (151), entered service with the Philippine Navy last year.

Apart from these two frigates, the Philippines relies mostly on smaller ships, such as corvettes and patrol vessels. Regarding the former, in December 2021 the Philippines ordered two HHI corvettes for EUR 571 million. These ships, to be delivered by 2026, will enhance Manila’s anti-ship and anti-submarine capabilities. They will join another ship to be delivered from South Korea, the ROKS ANDONG (771) POHANG class corvette, which was built in 1987 and retired in 2020. One ship of this class, the BRP CONRADO YAP (PS-39), is already in service with the Philippine Navy. Unlike Indonesia, which requested to partially move production to local companies, all ships for the Philippines will be constructed in South Korea.

In January 2022, Manila requested the BRAHMOS coastal-based anti-ship missiles for EUR 340 million. The acquisition will significantly boost the anti-access capabilities of the Philippines and thus its conventional naval deterrence vis-à-vis China. For now, such capabilities in South-East Asia are limited to Vietnam and Indonesia, both of whom have P-800 YAKHONT anti-ship cruise missiles, the former possessing the missile as part of its K-300P BASTION systems, and the latter in frigate-mounted form.

The Philippines has an ambition to acquire at least two submarines, with some sources mentioning a total requirement of six. The country sent personnel to abroad to train in submarine operation back in 2018, with the intent to procure submarines by 2027. However, due to significant financial constraints this goal is unlikely to be met. Navy chief Vice Adm. Adeluis Bordado stated: “Hopefully, we will have submarines in the future when the economic situation improves”, explaining that “if not for the pandemic, we would have pushed through with the submarine acquisition”.

Malaysia

Malaysia appears less exposed to Chinese regional ambitions than Indonesia and in particular the Philippines. However, the relationship is not entirely trouble-free. Chinese vessels have previously entered the Malaysian-claimed James Shoal and Luconia Shoal, and have reportedly interfered with Malaysian energy exploration activities. Nevertheless, these emerging issues have not changed Kuala Lumpur’s naval plans, at least for the time being.

The Royal Malaysian Navy has adopted a reduction plan known as 15-5. Its intention is to reduce costs, simplify supply chains and maintenance, and improve readiness. Instead of 15 ship classes, Malaysia wants to have only five classes, comprising: 18 patrol vessels, 12 littoral combat ships, 18 littoral mission ships (LMSs), three multirole supply ships and four submarines. Although Malaysia already possesses two SCORPENE class submarines, under the plan it will need to procure two further submarines, with one between 2031-2035 and another one between 2036-2040.

Malaysian modernisation is rather slow. Due to delays and cost overruns, one of Malaysia’s flagship projects, the construction of six littoral combat ships built by Boustead Naval Shipyard, will not be delivered on time. The first ship was launched in 2017 and scheduled for delivery in 2019, but by August 2022 Defence Minister Hishammuddin Hussein admitted that the first ship would be completed in “at least a year or two”. Moreover, there are some controversies surrounding onboard systems. The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) warned in August 2022 that “The SETIS system chosen by the minister is not only more expensive, it has yet to be fully developed, and is also at risk of becoming obsolete in five to 10 years”. It is worth adding that the Royal Malaysian Navy had originally wanted to use the TACTICOS system and SIGMA class ships from the Netherlands.

Four LMSs were procured from China, the final KERIS class ship was delivered by China’s Wuchang Shipbuilding Industry Group in December 2021. Under initial plans, the last two vessels were intended to be manufactured by Boustead Naval Shipyard in cooperation with China Shipbuilding & Offshore International, but later all works were moved to China. More orders from China are unlikely, with Malaysia recently looking for a different partner to complete the LMS programme.

Vietnam

Vietnam has already accomplished much of its naval modernisation. Relatively massive procurements after the 2000s were a result of China’s military build-up and more assertive policy in the South China Sea. Between 2014-2017 Vietnam successfully acquired an impressive number of submarines. Six HANOI class (Project 636.1) joined the service, which is a big boost to Vietnam’s naval capabilities vis-à-vis its neighbours, including China. Additionally, Vietnam procured four GEPARD class (Project 11661E) frigates and two ex-South Korean POHANG class corvettes. Vietnam has also worked to deepen its ties with both with the United States and Japan.

Those accomplishments do not mean that modernisation efforts have been completed. In March 2021 the Song Thu Corporation’s shipyard in Da Nang launched a fourth and a final Damen RoRo 5612 multipurpose vessel. This was the first ship of that class ordered by Vietnam, three vessels were previously ordered by Venezuela but were never delivered. Vietnam was also recently provided with an ex-US Coast Guard patrol boats, including the former USCGC JOHN MIDGETT in 2020 and the former USCGC Morgenthau in 2017. The US has also donated 24 Metal Shark high-speed patrol boats to Vietnam, with the final six delivered in May 2020. In July 2021 Vietnam’s Z189 shipyard in Haiphong supplied the Vietnamese Navy with the MSSARS 9316 (Yet Kieu 927) multi-purpose submarine search and rescue vessel.

Under a EUR 103 million credit line, India built five high-speed patrol boats for Vietnam, with the first delivered in December 2020, and an additional seven boats are under construction at the Hong Ha Shipyard in Haiphong, under the supervision of India’s Chennai-based Larsen & Toubro shipyard. All 12 boats are due to be delivered to the Vietnamese Coast Guard. Indian-Vietnamese defence ties are the result of growing political and military cooperation, for instance, in February 2022 Vietnam’s QUANG TRUNG frigate (HQ-016) and a delegation of the Vietnam People’s Navy attended the MILAN 2022 multilateral naval exercise in India. This was the first Vietnamese deployment to these drills.

Other states

Both Singapore and Thailand have been pursuing new submarines, with different levels of success. Singapore ordered four Type 218SG submarines as a replacement for its CHALLENGER class and ARCHER class submarines. Three boats are under construction, with the first of class, RSS INVINCIBLE, expected to be commissioned later in 2022.

The Royal Thai Navy’s path has been less easy – in 2017 Bangkok signed a contract with China’s Shipbuilding & Offshore International to buy up to three S-26T submarines (039A YUAN class). Doubts as to whether these were needed gained traction as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic recession. Finally, in August 2020 Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha announced that all down payments for the second and third submarines would be frozen. Moreover, Germany refused to supply MTU396 engines for the submarines due to export rules. It means that delivery of the first ship, originally scheduled for 2023, will not be possible. Bangkok rejected China’s proposal to transfer two used SONG class submarines as a stop-gap measure. Thailand’s other option is to use Chinese engines. Thailand does not rule out cancelling their deal with the Chinese, who in 2019 were also contracted by Bangkok to deliver one YUZHAO class (Type 071E) amphibious transport dock for roughly EUR 206 million.

Following the upgrading of two BANG RACHAN class minehunters by Thales, Thailand now wants to modernise two PATTANI class OPVs. So far Bangkok introduced two OPVs of the KRABI class (in 2013 and 2019) and has a plan to procure additional four OPVs. In terms of frigates, it is likely that Bangkok will decide to procure one additional frigate from South Korea, with discussions carried out between the respective defence ministers last December. Thailand commissioned the “Bhumibol Adulyadej” (471) frigate (DW3000F design) from Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering in 2019. According to long-erm modernisation plans, Thailand is expected to procure two modern frigates.

Internationally isolated Myanmar could overtake Thailand on the way to acquire a new frigate. As put by “Asia Times”, this country has “a steady but little noticed build-up of naval power that has hinged on a growing fleet of surface combatants, notably frigates and missile corvettes that are mostly the product of an ambitious program of home-grown military ship-building”. The government in Naypyidaw, which in 2017 received first two out of four Israeli SUPER-DVORA Mk III gunboats, has already successfully procured two ex-Indian KILO class submarines and is now reportedly in talks with Moscow to buy one Project 636 submarine.

In December 2021 Myanmar commissioned an ex-Chinese MING class submarine and their second INCLAY class OPV, while one year earlier the “Yan Nyein Aung” (443) and “Yan Ye Aung” (446) submarine chasers entered the service, with a total of 10 planned. Additionally, Myanmar also has their ongoing indigenous FF-135 frigate programme, each of which will most likely be armed with eight C-802 anti-ship missiles.

Conclusions

Recent years have not brought any radical changes, and the main trends either continued or even strengthened. No changes in the region should be expected in the near future. The naval domain was prioritised by all Southeast Asian states, even Myanmar, where traditionally the navy had a low priority. With Beijing’s more assertive approach and its self-proclaimed “nine-dash line” in the South China Sea, Southeast Asian states have no realistic choice but to upgrade their fleets to enforce their own claims.

Regarding modernisation priorities in Southeast Asia, submarines have become a must-have. Almost all states have either already acquired them or are planning to procure submarines in the near future. Nevertheless, modernisation efforts include also other types of ships, including frigates, corvettes and patrol ships. It is worth noting that nowadays even smaller ships are armed with anti-ship missiles. As noted by Felix Chang, Asia Program at Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) in Philadelphia, regional thinking about naval modernisation programs “revolves around how to take advantage of (and defend against) the vulnerability of warships to modern guided missiles and the growing prevalence and sophistication of sensor technologies. Hence, all four of Southeast Asia’s largest maritime countries have prioritized the acquisition of warships that can not only launch long-range guided missiles, but also avoid easy detection”.

It is worth noting that leading states have been trying to establish national defence industries and bring some production home, although those attempts are not always successful. When it comes to suppliers, Europe is still an important industrial partner, but South Korea has finally found its place too – Seoul had some noteworthy successes and has become a serious market competitor to more traditional suppliers. In the near future it is likely that South Korea will improve its position further.

Robert Czulda