As the EU remains under continued migratory pressure and the scope and budget of Frontex are significantly expanding, the Agency’s efficiency in the management of EU external borders is under scrutiny.

Since 2019, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, better known as Frontex, has been undergoing an important build-up to better fulfil its new role as guarantor of the European integrated border management and internal security. To this end, the number of border guards will ramp up from the current figure of 2,000 to 10,000 by 2027, with €5.6Bn allocated annually to the Agency in the same timeframe. With a possible reform of the Schengen area expected under the ongoing French Presidency of the European Council and the continued migratory pressure on the EU, Frontex might become more crucial in the future. However, the fact that the redeployment of its assets and border guards must be requested by Member States makes the Agency somehow unexploited. Worst still, criticism continues to mount, especially concerning the management of illegal migration at the EU’s external borders, with NGOs and EU institutions closely looking at Frontex’s methods and governance. Per these considerations, this article will focus on this matter.

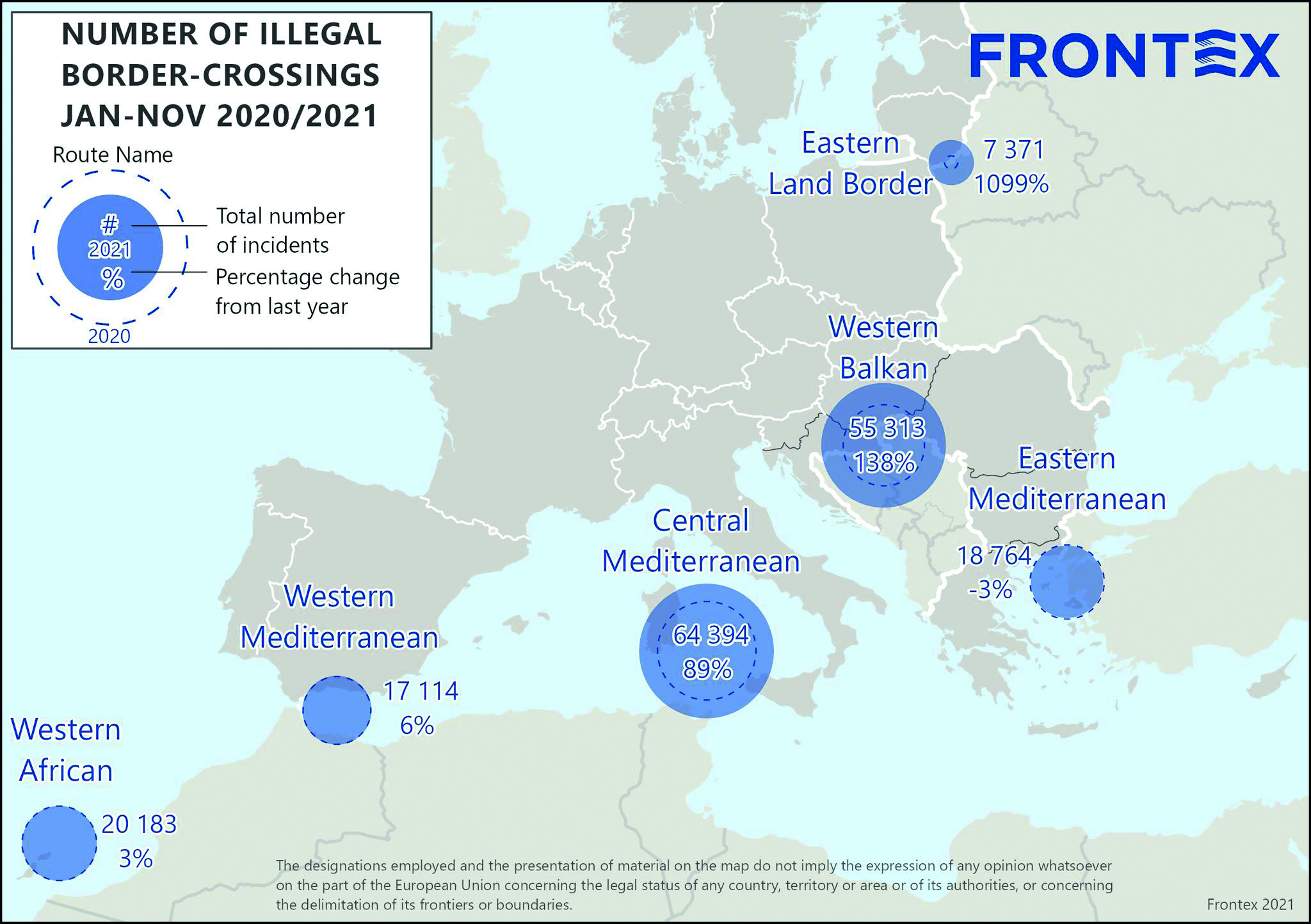

The Most Relevant External Border Protection Missions in 2021

In 2021, Frontex was involved in four main operations. Poseidon (Greece) and Themis (Italy) represented the main border surveillance operations in the Eastern and Central Mediterranean, respectively. These joint missions, mainly devoted to monitoring the illegal flux of migrants and save lives at sea, have been ongoing for several years now. Intelligence gathering and information sharing on human smugglers are a crucial part of both operations, with Themis also having a focus on terrorist groups and foreign fighters.

Frontex vessels, aircraft and personnel are also present off the Spanish coast with Operations Minerva and Indalo, aimed at combatting human trafficking and organised crime in the area stemming from Morocco. The Agency also operates in the Western Balkans, where it assists Member States in addressing the migratory pressure at the external land border and fighting against cross-border organised crime. From 6 December, a Danish patrol aircraft arrived in Lille (France) to enhance surveillance operations carried out by the French, Belgian, and Dutch to fight against illegal migration in the Channel. This is a mission that French Interior Minister Darmanin defined as a “great victory”, following repeated French calls for support for the management of illegal crossings from France to the UK. The number of migrants who have tried to reach the British coast on small boats has tripled in 2021 compared to 2020, and 30 people died last November in the worst migrant mass drowning ever recorded in the area. The incident revived tensions between the UK and France, and might end in a revision of the Le Touquet treaty on migration control, signed in 2003 to establish border management rules between the two parties, as the UK is not part of the Schengen Area. The reform of this Treaty and of the Schengen area are expected to gain momentum under the French Presidency of the EU Council, to last until June 2022.

Efforts to Increase Accountability and Transparency

However, the ongoing in-depth investigations launched by different EU institutions and agencies in response to numerous complaints about Frontex’s internal and external activities (see ESD 06/2021) might negatively affect the Agency’s activities and undermine any further expansion of its mandate.

At the end of 2020, the European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, opened an inquiry upon her own initiative into the Agency’s Complaints Mechanism and the role of Fundamental Rights Officers for alleged breaches. Findings released in June 2021 confirm the need to improve the accountability of Frontex activities. To this end, the Ombudsman proposed a revision of procedures, including the possibility to accept anonymous complaints, and the amelioration of their transparency, within and outside the Agency. The European Parliament has also pursued investigations into the Agency’s management. The 14 MEPs of the Frontex Scrutiny Working Group (FSWG), established within the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, carried out their first fact-finding mission between February and June 2021. In their final conclusions, MEPs were not able to prove any “direct performance of pushbacks and/or collective expulsions by Frontex” in the serious incidents they examined.

However, they found that the Agency did not prevent them despite existing reports on allegations, and failed to respond to internal cases of probable human rights violations. The FSWG expressed its concern about the lack of cooperation by the Executive Director and found deficiencies in the monitoring, reporting, and assessing mechanisms on fundamental rights situations and developments. In October, during discussions on the next EU budget in plenary session, MEPs asked the European Council to freeze 12 per cent of Frontex’s budget for 2022 (€90M) and to make it available once the Agency had fulfilled specific conditions. This is not the first time that the Parliament makes such a request, which has been systematically rejected by the EU Council so far. The European Court of Auditors enquired about Frontex activities as well. According to the final report released in June 2021, the Agency failed to effectively implement the mandate received in 2016, supporting Member States in tackling illegal immigration and cross-border crime. In more detail, the Court found gaps and inconsistencies in the information exchange framework, with a consequent negative impact on external border monitoring capabilities for both the Agency and Member States. Moreover, vulnerability assessments and risk analyses are not always supported with the complete and good-quality data needed. Auditors also accused Frontex of a lack of transparency in detailing the real costs of operations, which remain underdeveloped in the Agency’s daily activities. Consequently, the Auditors cast doubt on the capacity to carry out additional missions despite an increased budget and equipment. “At a time when Frontex is being given added responsibilities”, the situation is particularly worrying, commented Leo Brincat, the Auditor in charge of the report.

In a first response to critics, the Agency appointed numerous Fundamental Rights Officers, with the delay in the appointment being one of the main criticisms received in recent years. The first annual report of the Fundamental Rights Office released last summer and concerning 2020 activities, described how the Agency was evolving in taking on its new role. The document mainly blamed the pandemic and the related travel restrictions for limiting the extent of officers’ monitoring activities, especially those on-site. It also recalled the Office’s proactive engagement in monitoring and assessing fundamental rights risks, and its collaboration in the different investigations on alleged malpractices. It concluded that the Office would continue its efforts for developing and improving Frontex tools for fundamental rights protection and policy thanks to an expansion of its mandate and the establishment of a Fundamental Rights Due Diligence Policy, an internal tool for impact assessment.

Pursuing the Build-up Despite the “Crisis”

In the meantime, the Agency continues its activities, and plans to spend more than €150M in the next two years for surveillance in the Southern Mediterranean. The figure is far higher than the €27M (which eventually rose to €40M) spent in 2019 for leasing contracts with the Franco-Luxemburgish CAE Aviation, the British DEA Aviation and the Dutch EASP Air. The three companies provided coastal surveillance flights and medium to long-range sea missions. In parallel, Frontex activated new contracts concerning the use of UAVs, namely the Airbus Defence and Space HERON and Elbit Systems’ HERMES for patrolling missions in the same area. The Agency’s presence in Africa, especially in the West, might increase in the next years thanks to bilateral working arrangements. Two are already in place with Nigeria and Cape Verde, but more might come on line with the 2021-2023 international strategy, which seeks an expansion of Frontex activities abroad to better manage the influx of migrants wanting to reach the EU. Moreover, the Agency participates in different Horizon projects dedicated to border security funded under the EU Framework Programmes for research and innovation.

In addition to the build-up of its own capabilities through increased funding, Frontex promotes the pooling and sharing among Member States to make their border control capabilities more efficient. A significant part of Member States’ equipment pledged to Frontex for its operations is procured thanks to ad hoc European funds, namely the Internal Security Fund (ISF). Launched under the 2014-2020 EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), the ISF was established to enhance EU security through better law enforcement cooperation and external border management. Based on national operational requirements, the ISF might cover 75, 90 or 100 per cent of each project. In its 2014-2020 configuration, the ISF was split into a Police component and a Border and Visa component. The first focused on the fight against organised crime and the management of security-related risks, while the second specifically supported an effective common visa policy and processing within the Schengen area and the protection of the external borders. Effective information sharing among Member States and also between these States and Frontex were part of this second instrument. The division into two different tools has been abolished for the 2021-2027 period. A share of the €1.9Bn-worth fund (four times less than in the previous MFF) is devoted to the so-called Thematic facility, which implements and replaces the

2014-2020 IFS-Police instrument, to be used for “emerging or unforeseen needs”. This includes, among others, a “Common Operational Partnership to prevent and fight against migrant smuggling with competent authorities of third countries”, aimed at expanding cooperation to third countries with the involvement of EU agencies (Frontex included) when possible. Thanks to this fund, several Member States have been able to expand or modernise their existing fleets with significant EU financial support. In 2019, Greece bought four state-of-the-art patrol vessels, built by the Italian Cantiere Navale Vittoria, co-funded at a rate of 90 per cent by the ISF for its Coast Guard. This year, Romania received €26M for the purchase of two maritime patrol vessels for its Border Police. The two ships, due to be built in the Dutch Damen’s local construction sites, were specifically procured as a “means of naval mobility necessary for Frontex”, according to the contract notice. As a consequence, the need for better managing migration justifies Member States’ procurement for dual-use assets, and allows them to receive EU funds for this. In the meantime, Frontex can rely on national assets, as it would be difficult for States to not to pledge units purchased thanks to EU funds.

A Future Perspective

The 2015 migration crisis had already demonstrated the existing capability gaps in the protection of the EU’s external borders, which had not been sufficiently filled when internal borders were abolished in 1992. As Frontex Executive Director Leggeri reaffirmed in recent interviews, the illegal migratory pressure on the EU will likely increase further in the coming years due to mounting instability at the bloc’s gates. The situation occurred some months ago along the Belarus-Polish border, which the European Commission defined as a form of hybrid warfare, representing the most recent example.

In any case, the future of the Agency will heavily rely on Member States’ willingness to effectively speak with one voice on migration. As they perceive border management as a national power prerogative, they struggle to find a balance between effectively protecting borders and asking for help to do so. The operation launched in France in December is a notable example. Frontex has been offering help for more than a year, but Paris refused the use of a British plane for the mission for political reasons. Moreover, the appointment of Fundamental Rights Officers to monitor each operation and ensure the respect of human rights on the terrain has not always been perceived as good news by all Members States. Indeed, they will be considered as being responsible for the violations perpetrated by their border guards. In response to more than 500 incidents reported, Lithuania has reduced its personnel seconded to Frontex from 120 to 40 service members.

Furthermore, Member States have not settled their divergences concerning the bloc’s migration policy. The approval of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, proposed by the European Commission in September 2020 and aimed at redefining the EU’s approach towards illegal migration, is far from being approved. This complex political scenario has an important impact on Frontex’s activities. On the one hand, the Agency has probably never been so important, as its planned build-up demonstrates. On the other, the lack of a common EU approach on migration undermines its efficient and effective use, as well as the mismanagement accusations.