The US Army Futures Command (AFC) celebrates its fifth anniversary in August 2023. The Pentagon created this dedicated command in the hope of avoiding the kinds of mistakes that had plagued numerous development and procurement programmes in recent decades and delayed much-needed replacement of legacy systems. Many observers see 2023 as a pivotal year for the Army’s ambitious modernisation efforts.

The bottom-line goal of these efforts is straightforward. The Army needs to enhance lethality, mobility and survivability in order to compete and win on the future multi-domain battlefield. A major factor will be retaining – and in some cases regaining – technological and operational superiority over peer/near-peer opponents. While US and other Western military equipment is generally considered superior to those of adversary states, some rivals – taking advantage of the Pentagon’s two-decade long focus on counterinsurgency – are making considerable headway in such areas as long-range artillery, air defence, and cyber operations. The most dramatic area may be hypersonic weapons, which both China and Russia managed to introduce before the United States did.

While the US Army is planning to introduce a large number of individual weapon and support systems, a major element of the future combat capability enhancement lies with multiplier technologies which are intended to fuse the various elements into an operational system which is much more than the sum of the individual components. This will require transitioning to a more data-centric force in which individual vehicles, aircraft, robots, and even infantry soldiers and their weapons can be wirelessly connected on the digital battlefield.

Other favoured innovations will include: enhanced (longer range, greater precision) firepower for combat systems; increased reliance on automation, autonomy and artificial intelligence (AI); reduced logistical footprint and improved sustainability in the field. Technologies designed to facilitate these developments include modular open-system architectures (MOSA) to enable the seamless addition or replacement of hardware and software components; this will ensure that all platforms and systems can be kept at state-of-the art performance throughout their service lives.

Credit: Army Futures Command

Priority Programmes

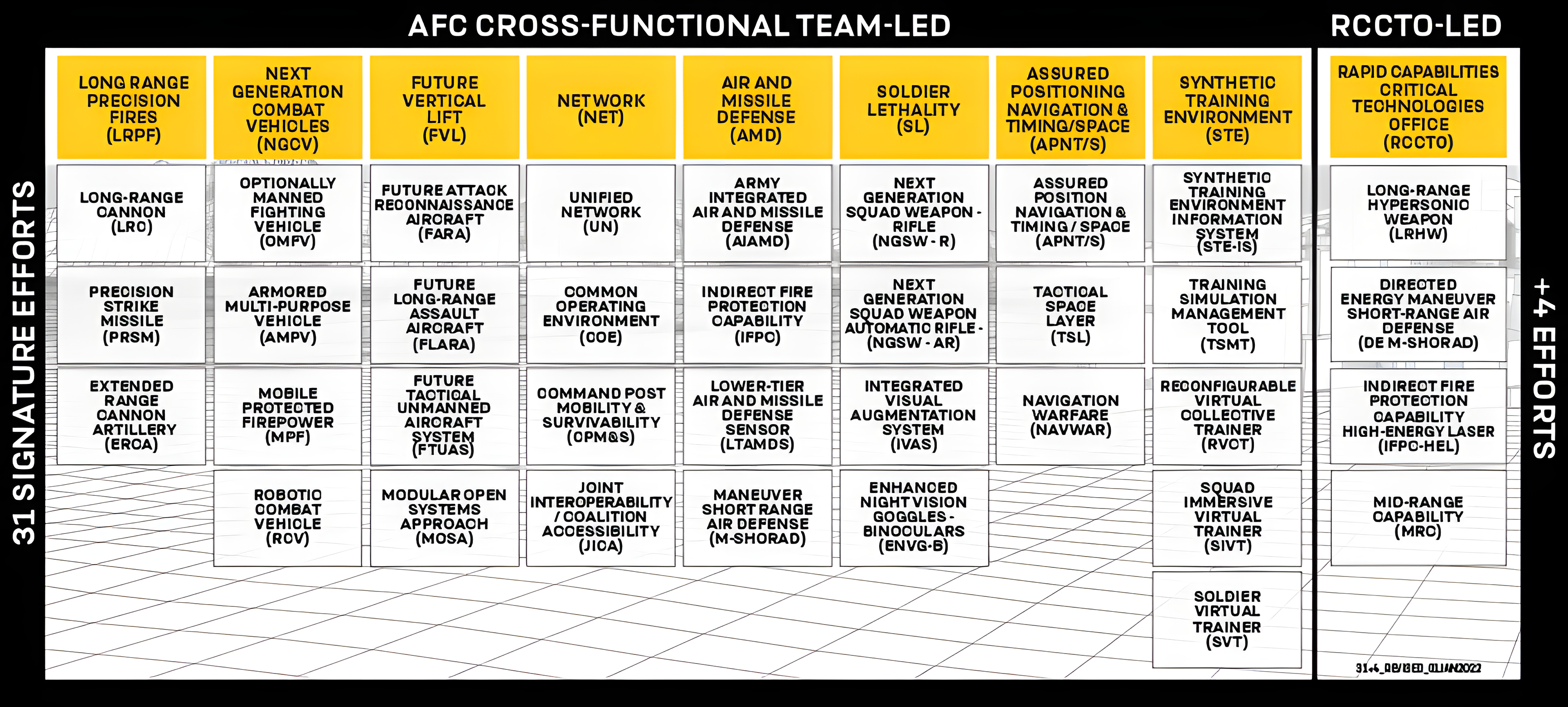

While the ongoing US Army modernisation programme encompasses more than 500 development, acquisition or upgrade efforts, the core rests with 35 new “future force” systems, which are supposed to be fielded by 2030. Army Futures Command is overseeing 31 of these programmes, which it refers to as “signature efforts”; the remaining four are under the aegis of the Pentagon’s Rapid Capabilities Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO). The 2023 budget document foresees operational fielding or operational testing of two dozen of these 35 systems by the end of Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23). Some of the programmes are utilising advanced prototyping and experimentation to fast-track development. The introduction of digital design and virtual experimentation processes is also shortening development programmes, sometimes significantly.

The Army has grouped its prioritised development and acquisition programmes into six capability portfolios. These are: Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF); Next-Generation Combat Vehicles (NGCV); Future Vertical Lift (FVL); Network, Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD); and Soldier Lethality.

Long-Range Precision Fires

Long-Range Precision Fires is designated as the foremost priority among the modernisation portfolios, largely as a reaction to Russian and Chinese progress in long-range tube and rocket artillery. The LRPF portfolio is scheduled to move forward across the board during FY23. Both the 155 mm Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) designed to deliver enhanced rocket-propelled shells onto targets 70 km distant, and the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) with an initial 2,800 km capability, are scheduled to equip their respective first batteries this year.

Credit: US Army

During 2023, the Army also expects to receive the first of 54 Precision Strike Missiles (PrSM, 500+ km range) which were ordered in December 2021; operational testing is scheduled for 2024, with an initial operational capability (IOC) expected in FY25. The PrSM is intended to engage high-value tactical targets, and will be fired from existing M270A1 MLRS and M142 HIMARS launchers.

The Strategic Mid-Range Fires (SMRF) system, also known as the Typhon, will be fielded in FY23, only two years after development began. The first prototype battery was delivered to the Army in November 2022, with one additional battery to be delivered in each of the following three years. The concept modifies US Navy SM-6 and UGM-109 Tomahawk missiles for deployment from ground-based launchers. The 500-1,500 km operational range falls between the PrSM and the LRHW.

Next-Generation Combat Vehicles

Tangible progress is being made within the tactical ground vehicle portfolio. In 2022, the Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) light tank transitioned to Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP), with a goal of equipping the first light infantry unit in 2025. The Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), intended as replacement for the Vietnam-era M113 armoured personnel carrier, overcame numerous technical issues and passed operational testing in 2022; a full-rate production decision is slated for FY 2023. Downselect for prototyping the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) is scheduled for 2023; the Army still expects to equip the first combat unit with the OMFV in FY28, initiating the long-term transition from the Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV).

Credit: US Army

The fourth element of the NGCV portfolio is the Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV) programme, which is subdivided into light, medium and heavy-vehicle development programmes (RCV-L, RCV-M and RCV-H, respectively). The RCVs are intended to support and operate with manned fighting vehicles, with roles ranging from reconnaissance to combat. The RCV-H has currently been de-prioritised. Intensive evaluation of RCV-L and RCV-M surrogates began in 2022.The Army intends to award engineering manufacturing and development (EMD) contracts for the RCV-L in late FY23, with a production decision expected no later than FY27. The decision whether to pursue an EMD for the RCV-M is expected during FY24.

Future Vertical Lift

The Future Vertical Lift (FVL) programme currently encompasses the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) and the Future Attack and Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA). Bell Textron Inc. was selected in December 2022 to build the FLRAA, which is destined to ultimately replace the UH-60 Blackhawk. Bell’s competitor Sikorsky contested the contract award in late December. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) is required to rule on the protest by the first week of April 2023. While challenges only rarely succeed, an overturn of the contract award remains possible. The Pentagon generally factors contract-related delays into its timelines. In that light, Sikorsky’s challenge is not expected to significantly impede the Army’s goal of fielding the new aircraft in 2030.

Credit: US Army

FARA is the intended replacement for the AH-64 Apache in the attack- and scout-helicopter role. The Army has acknowledged that its stated goal of fielding FARA by 2030 is ambitious, but continues to stand by that schedule. Government flight testing of the two competing prototypes (again being offered by Bell and Sikorsky) is expected to begin by late FY23, with a production award slated for 2028.

FVL also encompasses the Future Tactical Unmanned Aerial System (FTUAS) component, which is being procured in two increments. In August 2022, the Army awarded AeroVironment Inc. the Increment 1 contract, which will introduce the Arcturus Jump 20 UAS as replacement for the RQ-7B Shadow UAS in FY23. The service is currently reviewing competing submissions for the Increment 2 procurement, which will introduce a second type of tactical UAS.

Network

While hardware might be the most visible modernisation aspect, the digital element could well be the most crucial. Networking the many vehicles, platforms and hardware systems is considered the key to maximising their tactical performance. The establishment of a “tactical cloud” to connect disparate weapon and sensor systems remains a core aspect of US Army modernisation. This will ensure interoperability and a common operating picture for the joint force and coalition partners.

The Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) will connect multiple offensive and defensive platforms, weapons and sensors to significantly enhance the chance to quickly and effectively engage enemy targets of all kinds. The IBCS underwent initial operational testing and evaluation in 2022 and into 2023, with a full-rate-production decision to be made later in FY23.

Other elements of the Network portfolio include the Unified Network and the Common Operating Environment. The former will encompass an integrated tactical network and an integrated enterprise network, and will facilitate networking of individual communications and data systems. The latter will integrate databases and provide mission commanders with a unified set of command applications. Finally, the Network portfolio aims to enhance mobility and reduce signature emissions of mobile command posts.

Integrated Air and Missile Defence

The Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) portfolio aims to develop a tiered, multi-layered system to defend fixed sites and manoeuvre forces against the full spectrum of short- to long-range low-altitude threats. Some programmes are under the aegis of Army Futures Command, with the remainder being pursued by the joint service RCCTO. The Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense System (LTAMDS) will serve as the IAMD’s primary radar, although it will not replace all other air defence radar systems. It will be platform-independent, feeding warning and targeting data to various interceptor systems. The Army plans to field the first LTAMDS battalion, consisting of four sensors, by the end of FY23.

New air and missile defence interceptor systems are being prepared. These include the Directed Energy Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (DE-M-SHORAD) system, which is based on a Stryker vehicle armed with a 50 kW laser. The primary mission will be defending tactical army units from UAS and manned helicopters, as well as incorporating a counter rocket, artillery and mortar (C-RAM) capability. The first four-vehicle prototype platoon is slated for operational testing in early 2023. The Maneuver SHORAD (M-SHORAD) system, also based on a Stryker vehicle, became operational in October 2021 with a permanent overseas presence in Germany. Instead of a laser, this system employs kinetic weapons including Longbow Hellfire missiles, Stinger missiles, and a turret-mounted 30 mm gun. Targets include UAVs, cruise missiles, helicopters and low-flying fixed-wing aircraft.

Beginning in May 2019, the Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC) programme (managed by the RCCTO) initially tested the truck-mounted High Energy Laser Tactical Vehicle Demonstrator (HEL TVD) developed by Dynetics, with the goal of fielding a 300 kW system to intercept UAS and other airborne threats. In January 2022, the RCCTO issued a Request for White Papers (RFPW) from potential prime contractors for the IFPC Increment 1 procurement track, officially designated the IFPC-HEL. The RFPW’s stated goal was delivery of up to four complete high-energy laser weapon systems to be delivered no later than the fourth quarter of FY24 in preparation of live range testing against operationally relevant targets.

Meanwhile, in September 2021, the Army selected Dynetics’ Enduring Shield system for the IFPC Increment 2 after a shoot-off against Rafael’s Iron Dome. The palletised launcher accommodates multiple modified AIM-9X interceptor missiles capable of shooting down manoeuvrable airborne threats including subsonic cruise missiles and UAS; by 2026, the system is supposed to add a C-RAM capability. Citing supply-chain issues, Dynetics is currently behind schedule delivering the first four prototype launchers for operational testing, but the Army expresses confidence that system testing will still begin during FY23.

The contract calls for 16 prototype launchers and 80 “fieldable” AIM-9X prototypes to be delivered through 2024, with an option to procure 400 operational launchers following testing. Transition to a programme of record is planned for FY25. In January 2023, the Army issued a contracting notice requesting information regarding the feasibility of augmenting the AIM-9X with a second interceptor type, this one capable of defeating supersonic cruise missiles and large calibre rockets.

Credit: Dynetics

Soldier Lethality

Ten-year procurement contracts for the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) programme were awarded to Sig Sauer in early 2022. The first infantry unit is expected to be equipped by the fourth quarter of FY23. NGSW replaces the M4 carbine, the M249 light machine gun, and the M240 machine gun with the M7 rifle and the M250 automatic rifle (machine gun), both chambered for newly developed 6.8 × 51 mm ammunition. Vortex Optics will build the Picatinny rail mounted firing computer (FC) for the new infantry weapons. The FC sights will provide the option of 1x to 8x magnification; more importantly, the active reticle fire control system will calculate variables such as wind and bullet drop, and automatically adjust the sight’s point of aim. Overall, the NGSW is attributed with a significant improvement in range, accuracy, lethality and portability when compared to current arms and ammunition.

Credit: US Army

The Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) is also classified as a Soldier Lethality tool as it provides enhanced situational awareness. The Army plans to begin fielding the augmented reality goggles to training and recruiting units in September 2023, followed by infantry units in 2024. In early January 2023, the service announced that it was already tasking Microsoft with developing a new variant dubbed IVAS 1.2, primarily to address soldier complaints regarding discomfort, fatigue and injury experienced when testing the cumbersome device.

Enhanced training capabilities designed to prepare soldiers for top battlefield performance constitute another major element of this portfolio. These training systems are collectively designated as the Robust Training Environment. Component systems to be delivered to the Army during FY23 include: the Reconfigurable Virtual Collective Trainer (RVCT), designed to enable unit collective and combined arms training for ground units and for non-rated aircrew; and the IVAS Squad Immersive Virtual Trainer. The Soldier Virtual Trainer (SVT) will round out the training systems when it achieves full operational capability in 2025; it will support individual weapon skills development, joint fires operations training, and escalation of force training at the individual and unit level. All of these systems will utilise a Synthetic Training Environment (STE), which will portray a common three-dimensional scenario for all participants.

The Journey is the Destination

General James McConville, Army Chief of Staff, has stressed that initial fielding of a weapon does not constitute the end of the modernisation programme. “What is really important is getting to the Alpha model,” McConville said in late 2022. “If you get the capability, get it in the hands of soldiers, then we’ll incrementally improve it.” In this light, the full impact of the new systems might not be felt until well into the 2030s. By that time, the Army will be pursuing yet more new vehicles, weapons and sensors to exploit the latest technological developments and operational concepts. “Military modernisation” is in fact a constant effort, not a finite goal to be accomplished.

And while the 35 signature technologies currently being discussed are considered critical, all of the many lower profile acquisition or upgrade programmes are expected to contribute to the future force. Additionally, some projects not included among the 35 signature programmes are high profile and high impact. The Abrams M1A2 SEPv4 Main Battle Tank (MBT) upgrade is a prime example. According to the Army, the combination of new sensors and targeting systems, improved power system, the new Advanced Multi-Purpose Round ordnance, the Trophy Active Protection System and upgraded onboard diagnostics will make the SEPv4 the most lethal Abrams of all time. The Army plans to begin fielding the upgraded variant during the first quarter of FY25. In the meantime, the M1’s developer, General Dynamics Land Systems, presented the AbramsX technology demonstrator in 2022. That design, incorporating new technologies such as hybrid propulsion, increased use of AI, and the capability to control unmanned vehicles, could bridge the gap until introduction of a completely next-generation MBT, or could simply serve to test various technologies which might ultimately flow into the next generation MBT.

Credit: GDLS

Maintaining Momentum

Force modernisation is resource intensive, as is sustainment of current readiness. The Army’s 2023 budget request included USD 35 Bn for acquisitions and research, development, test and evaluation (RDT&E). This constitutes 19.7% of the total Army budget request of USD 177.5 Bn. In late 2022, the coming year’s defence budget largely appeared to be a done deal. Following the 2022 Congressional election, a vocal – and potentially influential – minority in the House of Representatives has begun pressing for defence spending cuts which could cap budgets at 2022 levels. While such an extreme scenario is considered unlikely, it cannot be excluded that the Army may need to choose between deferring one or more developmental programme, or accepting increased risk to current readiness.

The impact of the war in Ukraine on the US Army’s modernisation programme is another source of uncertainty. “It’s a little early to translate lessons learned from Ukraine into all of our requirements process for our major weapon systems,” Army Under Secretary Gabe Camarillo told reporters on 7 December 2022. Overall, Pentagon planners postulate a need to maintain the general force structure construct, which is centred around MBTs, IFVs and artillery. Within this context, there remains room for change. As US Army Brig. Gen. Geoffrey Norman, Director of the Next Generation Combat Vehicles Cross Functional Team, asserted in late 2022, the service is monitoring which weapon systems are destroying MBTs in the current fighting. “Is it tank-on-tank direct fire engagements or is it top attack from anti-tank guided missiles [or] artillery sensor fuzed munitions,” Norman commented in October 2022. “We’re taking a hard look at that. […] How are we protected against that? What, if anything, do we need to do differently, both from the material standpoint, but also from a tactics and a doctrine standpoint.” The same holds for tactical helicopter systems, where the Russian Armed Forces seem to have suffered significant losses and operational restrictions. The performance of current Western weapon systems and the tactical capabilities of western and Russian systems by type will certainly flow into US force structure modernisation.

Overall, Army leadership is attempting to balance confidence in the modernisation process while projecting realism. “Progress generally is going very well,” said Army Secretary Christine Wormuth in October 2022. “Given that we have 24 systems in one year that we’re either trying to start fielding or we’re trying to get prototypes in the hands of soldiers, we may hit some bumps in the road along the way. I think that is to be expected.”

Sidney E. Dean