It is one of the most famous capabilities to make a difference in Ukraine’s ongoing war, but how applicable is SpaceX’s Starlink satellite communications system to future military operations?

On 28th February 2022, four days after Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, mercurial billionaire Elon Musk, sent Starlink Satellite Communications (SATCOM) terminals to Ukraine. Starlink is SpaceX’s satellite broadband internet service. Musk is the company’s chief executive officer and founder. Ukraine experienced significant telecommunications problems as Russian attacks pounded their critical national infrastructure. As well as affecting traditional landline communications, Russia’s aggression also disrupted internet services. Maintaining internet coverage and access became an understandable top priority for Ukraine’s government.

Credit: Kyiv City Hall

Since these first deliveries, an estimated 23,000 terminals have been delivered to Ukraine, according to local media reports. These have been donated by SpaceX, financed by the US Agency for International Development, donated by foreign governments and purchased privately. Starlink has made its presence felt as hostilities have continued. The New York Times reported the terminals helped besieged Ukrainian troops maintain contact during Russia’s siege of Mariupol. The city on the south-eastern Ukrainian coast held out against Russian aggression for almost three months until its occupation on 20 May. Starlink terminals let troops stay in contact with their commanders, journalists to send their stories and relatives to keep in touch. The role of the SATCOM service in the siege earned Russian ire. It was sufficient for the then head of Russia’s Roscosmos space agency Dmitry Rogozin to publicly warn Musk he would “be tried as an adult” for his actions, though it is doubtful this warning will have caused its recipient much concern.

Starlink has not been perfect. In October 2022, the Financial Times reported that the service had experienced connection failures and outages. The reason for these failures was not clear, and the report said SpaceX had refused to provide any information to this effect. Such issues notwithstanding, it still appears that Starlink has made a valuable contribution in Ukraine.

Performance

Starlink terminals provide broadband internet access in a small, easily portable, package. The package includes the antenna and its base, a router and cabling. The whole lot can be fitted in a 2.3 m2 (24.9 square ft) box weighing 10.5 kg (23.2 lb). The dish is a relatively small 1.5 m2 (16.1 square ft), making it easy to conceal. SpaceX has stated the terminals provide between 20 and 220 mbps depending on the user’s tariff. Individual customers get between 20 and 100 mbps, while business customers get between 40 and 220 mbps. Household internet users typically get download speeds of circa 100 mbps and upload speeds of around 10 mbps. Thus, Starlink is already matching the data rates one might find in their own home, although latency may be slightly higher. The company says the terminals cost around USD 1,000 each.

Credit: SpaceX

The link between the satellites and terminals are providing via Ku-band frequencies of 12 to 18 GHz and Ka-band frequencies of 26 GHz to 40 GHz. The terminals use an electrically-scanned antenna steering the beam automatically ensuring continued connection with at least one satellite overhead. The space.com website said that, as of November 2022, 3,236 operational Starlink satellites are in orbit. The satellitemap.space website details the coverage these provide, which includes the United States, most of Europe (sans Scandinavia), and parts of the North African coast.

These satellites are in a Low Earth Orbit (LEO) around 550 km (297 NM) above Earth. This is typically much closer than standard military communications satellites. The United Kingdom’s Skynet-5 military communications satellite constellation has a mean altitude of 35,794 km (19,327 NM) during its orbits. Nonetheless, this still means the Starlink signal can be comparatively weak by the time it reaches a terminal on Earth. Open sources say that the signal leaves a satellite with 4.89 mW (66.89 dBW) of power. However, the terminal can receive a signal as weak as between 1.5 μW (-58.23 dBw) and 15 nW (-78.23dBW). Potentially, this can place the terminal at risk of jamming. A Ka/Ku-band jamming signal eclipsing these latter power levels could risk drowning out the satellite signal.

Nonetheless, the terminals have some safeguards. Ku-band and Ka-band signals have exceptionally narrow beams, hence the Starlink antennas are physically small. Anyone aiming a jamming signal at them would need a very precise aim to direct the signal into the antenna. The attacker would need to have the terminal in visual range to do this, which is not the easiest thing to do in wartime when it might require the attacker to be quite close to their adversaries using the terminal. Data carried over the network will be encrypted. Software in the terminal could be programmed to block off and ignore any signal without this encryption. As the antenna beam is electronically steered it could point away from the jamming source and towards another Starlink satellite in view.

It is noteworthy that Russian forces did try to attack Starlink. In October, space.com reported that the terminals were subjected to cyberattacks. These were quickly remedied using a software fix. The good news is this illustrates that Russian forces may not having jamming systems suited to attack the terminals. The author’s analysis is that the Russian Army does not currently have the capabilities to jam the frequencies Starlink uses. The fact that a cyberattack was able to succeed, no matter how quickly it was remedied, does illustrate vulnerabilities. As Starlink is sending and receiving IP data the injection of malicious code into the terminals will always be a risk.

The Pentagon

What is Starlink’s military potential beyond Ukraine? Dr. Bleddyn Bowen is an associate professor of international relations at the University of Leicester, in England’s East Midlands. He is an expert on the militarisation of space. Dr. Bowen says the military market has always been a key part of Starlink’s business model. He says that private sector SATCOM providers always have military and government clients at the forefront of their mind “to make ends meet.” To date, the civilian SATCOM market has been arguably niche, largely confined to users needing SATCOM in locations where conventional communications are unavailable: “Very few parts of the space economy are viable without military and governmental involvement,” he continued.

Towards the end of 2022, SpaceX revealed plans to formalise its offerings to the military and government via its Starshield service. Details of Starshield’s exact specification are sparse. Repeated enquiries to SpaceX by the author went unanswered. Media reports have said that the system will gather satellite imagery, provide communications and have additional space for unspecified government payloads. This seems to indicate that a new constellation of spacecraft will be launched to provide these services. Alternatively, future Starlink satellites may be designed from the outset with these payloads. The reports continued that the crucial ‘military/governmental’ part of the constellation is the encryption it will use to secure the communications. This will almost certainly be more robust than levels of encryption for the civilian Starlink service. In 2022 CNBC revealed US Air Force tests to evaluate networking aircraft, vehicles and fixed sites with Starlink.

Credit: SpaceX

The US military has an insatiable appetite for satellite communications. The Department of Defence possesses circa 33 individual satellites reserved for military communications. Despite this, it still leases epic levels of bandwidth from the private sector. DoD use of commercial SATCOM en masse commenced in the mid-1990s with the Commercial Satellite Communications Initiative (CSCI). Mandated by the US Congress the CSCI launched studies to determine the role private sector SATCOM provision could have within the DOD.

Nonetheless, the DoD’s uptake of commercial space services precedes this, notes space historian Dwayne Day: “The US military has been using commercial SATCOM services since the 1960s and was using them extensively by the 1970s and 80s. They have used commercial satellites in geostationary orbit for things like telephone and television transmissions to military bases around the world, and the relay of data from military weather satellites and even ballistic missile warning radars.”

Fast forward to today and the DoD is looking to take the plunge in funding a LEO broadband constellation as part of the Pentagon’s 2023 to 2027 spending plan, spacenews.com reported in June 2022. This seems to dovetail with precisely the type of service SpaceX is offering through Starshield. A SATCOM system using a similar architecture to Starlink is necessary if such a concept is to be militarily useful, cautions Day. “Starlink was not designed for military use, it has been adapted for that use … There are a lot of things that are usually requirements for mobile or transportable military systems, like encryption, anti-jam capabilities, ruggedness, and so on, and Starlink doesn’t have them.”

Contracts for the provision of commercial SATCOM to the DoD are handled through the US Space Force’s Commercial Satellite Communications Office (CSCO). In late December 2022, Space Force announced it had assumed responsibility for all military SATCOM systems possessed by the DoD. The CSCO plans to award commercial SATCOM contracts worth almost USD 2.3 Bn in 2023 and 2024. The spacenews.com report added that the contract to provide LEO broadband services is worth up to USD 875 M over ten years. The force has a strategy behind its employment of private sector SATCOM. The rationale is for existing and future Space Force-owned satellites to carry traffic, or provide capabilities, that SATCOM companies cannot. Voice or data traffic needing high degrees of protection and security could be carried over military constellations. Less sensitive or unclassified traffic could move across commercial SATCOM links: “For those frequency bands, coverage areas or specialised capabilities not offered by the commercial SATCOM industry, purpose-built constellations and payloads will be acquired.” As Dr. Bowen notes, “Secure traffic takes the priority on the government-owned constellations, everything else will go across the commercial networks.”

In some ways, the US has little choice but to rely on the commercial SATCOM sector. In turn, as Dr. Bowen argues, the commercial sector largely depends on US DoD SATCOM bandwidth leasing contracts. This symbiosis will only deepen in the future. A 2012 analysis written by David Furstenburg, then chairperson at NovelSat, said a single US Air Force Northrop Grumman RQ-4B Global Hawk uninhabited aerial vehicle needs around 500 mbps of SATCOM bandwidth to fly. This is five times the entire SATCOM bandwidth used by the US military during the 1991 Operation Desert Storm to liberate Kuwait. Back in 2010, estimates predicted the DOD would need 16 gbps of SATCOM bandwidth to support a large deployed joint force in a major war. In the twelve years between 1991 and the US-led Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, US military SATCOM demands rose from 100 mbps to 4 gbps.

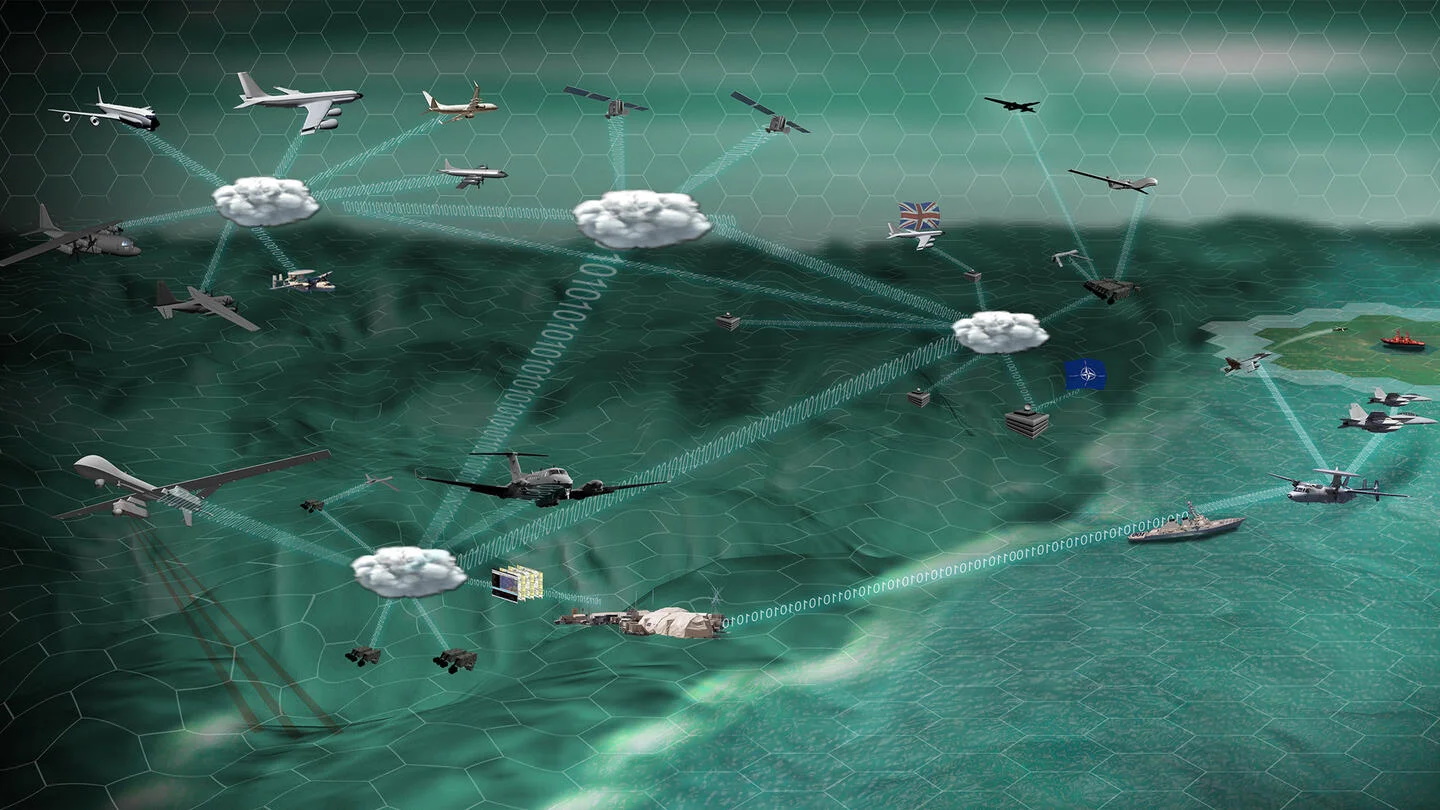

Increased US military SATCOM demands will be driven by two factors: The Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) concept and the Internet of Military Things (IOMT). JADC2 was launched in 2018 via the US National Defence Strategy. It federates stove-piped C2 systems used by the navy, air force, army and Marine Corps to ease information sharing within and between services. This will trigger an exponential increase in communications traffic. Moreover, these links will need to be intercontinental to support US expeditionary operations. Starshield could be well placed to provide the wide bandwidth, long range communications JADC2 will surely demand.

Credit: L3Harris

The physical size of the terminal could make it easy to deploy in space-constrained environments: “Starlink provides internet capability using a small terminal,” says Day: “Existing military and government systems can only provide some of that capability, but with bigger equipment.” Survivability is another big attraction. SpaceX could eventually field between 12,000 and 42,000 communications satellites, according to plans articulated by the company. This gives enviable survivability: “Taking out a few satellites, or even many of them, will not severely damage the network.” This is an important concern.

Several nations are exploring Anti-Satellite (ASAT) weapons using modified Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAMs). India, Russia, the People’s Republic of China and the United States have all performed kinetic tests of ASAT weapons. These weapons could participate in tomorrow’s wars, particularly given military reliance on SATCOM. Day believes one strength of networks like Starlink is their survivability: “Taking out a few satellites, or even many of them, will not severely damage the network” given the thousands of satellites equipping the constellation.

Erratic Actor

There is a catch. What is stopping a private sector provider pulling the plug if they decide that they are not being paid enough for their service? What happens if their management or owners disagree with the political aims of a war? At best, Musk seems eccentric, at worst erratic. The same Financial Times report said that Starlink provision was expected to cost SpaceX over USD 100 M by the end of 2022. In October 2022 the Washington Post reported that Musk had threatened to stop funding Starlink provision to Ukraine. SpaceX had asked the DoD to contribute to funding the service, and Musk warned the company “cannot fund the existing system indefinitely and send several thousand more terminals that have data usage up to 100 times greater than typical households. This is unreasonable.” He appeared to make the threat after Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany rebuked Musk’s proposal to end the war on terms seen as favourable to Russia.

Perhaps more concerningly, in early February 2023, SpaceX decided to impose restrictions on Ukraine’s Starlink access to prevent the system being used to control drones. In a statement during a during an 8 February conference in Washington D.C., Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s President and COO, stated that the service was “never meant to be weaponised” and that “Ukrainians have leveraged it in ways that were unintentional and not part of any agreement.” Such actions raise the question of how the DoD would avoid SpaceX, or any private sector SATCOM provider, switching off the service if they no longer agreed with a particular conflict, or if they believed they should be paid more?

Beyond the US

Will services like Starshield or Starlink have military appeal outside the United States? Possibly. The US is not the only country which is pledged to significantly deepen its level of military connectivity. In January 2022 the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) launched its Multi-Domain Integration (MDI) initiative. MDI is focused on “ensuring that every part of defence can work seamlessly together, and with other government departments and the UK’s allies, to deliver a desired outcome.” The MoD foresees deepening levels of integration within and between the UK’s armed forces. In addition, this level of connection will be replicated vis-à-vis other government departments contributing to the UK’s defence posture. These include the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), and the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). Likewise, robust links with external actors like the United Nations and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) will ensure information can be easily shared. The MoD does not specify exactly what capabilities will be delivered to ensure MDI becomes a reality. Nonetheless, improving communications links between these actors will be imperative. Although the UK already possesses the Skynet-5 SATCOM constellation, is there a role for the private sector to provide additional wideband links to carry less sensitive traffic?

Credit: ESA

Dr. Bowen does not believe that Starlink will necessarily find ready customers for Starshield-style services in NATO and allied nations, even if there is a strong demand. Space is becoming democratised. The miniaturisation of electronics and reusable rockets is reducing the costs of getting communications satellites into orbit. SpaceX plans a total of at least 12,000 LEO satellites in orbit, possibly increasing this to 42,000. In 2018, SpaceX estimated the entire programme will cost $10 billion. This gives each satellite a potential unit cost of between USD 238,095 and USD 833,333 depending on how many are eventually launched. The actual unit costs will probably be lower as the USD 10 Bn includes all costs associated with the programme. Nevertheless, a price tag of under USD 1 M for a communications satellite makes the technology attractive even for nations which do not have such capabilities. Furthermore, launch costs are reducing. The US Space Shuttle had launch costs of USD 54,500 per kg (2.2 pounds). SpaceX’s Falcon-9 and Falcon Heavy rockets reduce this to USD 2,720 per kg and $1,400 per kg respectively. This means that countries that previously refrained from developing military communications satellites on cost grounds could now develop this capacity. Having the global coverage of Starlink would require a lot more outlay. Nonetheless, if the country in question only wants a small constellation covering a specific area this would not be as expensive as in the past.

Paradoxically, this creates a challenge for SpaceX and other companies involved in private sector military SATCOM provision. As Dr. Bowen observes, some nations maybe keen to develop their space sectors and champion their own scientific endeavour and expertise by developing sovereign systems. This may now be noticeably more affordable than in the past. It could also help avoid potential pitfalls discussed regarding a private company providing, owning and operating a military SATCOM system on a nation’s behalf.

Starlink has made a difference in Ukraine and continues to do so. The US military is understandably interested in what Musk has to offer. Innovations like JADC2 will rely on greater SATCOM capacity than currently available. This will be mirrored in MDI initiatives around the world. “Starlink provides new capabilities, but is really only an evolution of previous options for military SATCOM,” says Day. The future will reveal the extent to which SpaceX can capture this market, as well as how far the DoD and others can rely on its services.

Thomas Withington