The Western arms industry is overstretched. With replenishment times for arms shipped to Ukraine alarmingly high, it is not enough for European armies to have quality suppliers. It is now also a question of being well-positioned in the delivery priorities of defence companies.

Over the past decades, European countries have allowed their weapon arsenals and ammunition stocks to run low. Instead of maintaining the knowledge base and lessons learned from major wars, governments and their militaries have cashed in on the peace dividend and adapted to the less demanding scenarios of expeditionary low-intensity warfare. In order to meet the materiel challenges Europe faces, only healthy supply chains can guarantee access to the materials, elements and components needed to manufacture at a rate not seen in decades.

To make matters worse, China has recently imposed sanctions on two American defence manufacturers over arms sales to Taiwan, Lockheed Martin Corporation and Raytheon Missiles & Defence, a subsidiary of Raytheon Technologies Corp. These sanctions came immediately after Beijing pledged to take countermeasures in response to Washington’s downing of a suspected Chinese surveillance balloon that entered US airspace at the end of January. Now these two entities will be added to China’s sanctions list[1] meaning they are banned from importing, exporting, and investing in China. The key word this time is ‘importing’, as that means a ban from importing all critical materials, mostly rare earth metals (also known as ‘rare earths’), refined and processed in the Asiatic giant. Without rare earths, there are no modern weapon systems. As such, now is a good time to revisit history.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

In past conflicts, securing the means to produce and keep weapon systems operational has proven decisive. Germany, a traditionally resource-poor country outside of coal and iron, learned this the hard way during WWI. Allies cut off maritime access to critical natural rubber and oil resources, compelling the IG Farben consortium to develop synthetic substitutes in the interwar years.[2] Likewise, the WWII Allied powers successfully restricted German access to Tungsten (known as ‘Wolfram’ in German). The metal was in a sense equivalent to today’s rare earths, due to its novel applications and importance in munitions and armour production. The Allied bloc pressured an ostensibly neutral Spain to stop providing Tungsten from the Galician region in Spain to Nazi Germany, in order to weaken its capabilities. The US instead became the main buyer of Spain’s Tungsten, and the Allied maritime blockade prevented overseas access to the precious metal. Even prior to the war, Great Britain expropriated German-owned Tungsten mines in England. As a result, Germany was forced to resort to sifting through tailings from zinc mining, where the precious metal was heretofore considered a useless by-product; such was Germany’s hunger and desperation for this critical raw material.[3]

Credit: Royal Navy, via Wikimedia Commons

After WW2, the US Government began a comprehensive study regarding access to critical materials needed in wartime.[4] Likewise, the US enacted the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to help ensure the US retained the industrial base and raw materials for all government programmes, including defence-specific applications. However, even as the US passed supplements specifically regarding rare earth metals in 1973, the growing neoliberal ideology meant that the world’s greatest military power would soon forget hard-learned lessons. Once the champion of globalisation, the US is now forced to create a Supply Chain Task Force[5] to reassess the security of its supply chains. The task force’s results highlight the precarious nature of US supply chains, with rare earth metals playing an especially critical role.[6]

Despite procurement rules stipulated in both the FAR and the Berry Amendment, the US Department of Defense (DoD) and its army of contractors routinely waive sourcing requirements, particularly regarding rare earths. In this regard, several defence companies have supplied weaponry containing Chinese rare earths to the US Government. Sub-contracting outsourcing was identified as the source of the violations, but the US Government was forced to issue an exemption to keep building weapon systems such as the F-35[7], also in the service of several European militaries.

Credit: Pixabay

It therefore seems that we are forgetting a key lesson gained from the two world wars of the 20th century. Mastery of the periodic table makes it possible to produce the best weapon systems, while secure, vertically integrated logistics supply chains are key to victory in any protracted conflict.

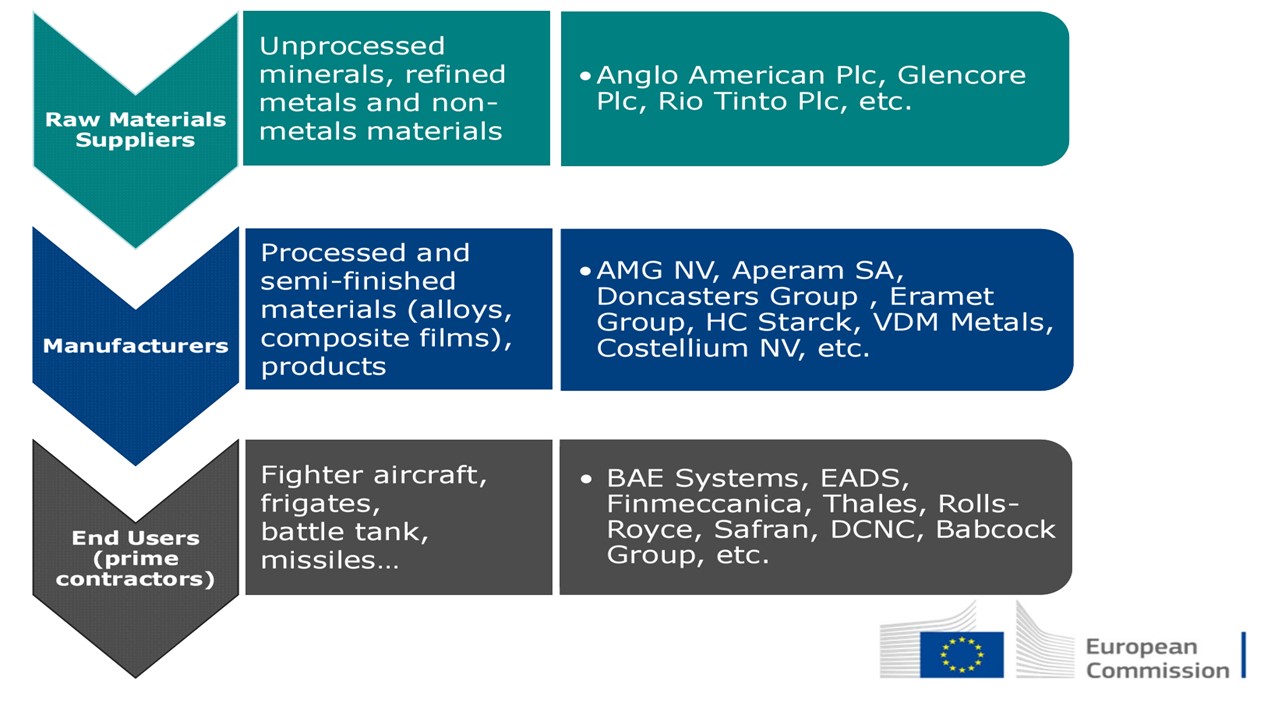

Subcontracting and ‘Just-In-Time’ Culture

The US has identified these issues rather early, but in the EU, whose Common Security and Defence Policy is still in its adolescence, members have not yet come to grips with the problem they are and will continue to face. Economies of scale these past few decades have led to the emergence of large European companies such as EADS (now Airbus), Rheinmetall, Leonardo, Thales, Safran, and Indra, loosely bound together through agencies and agreements such as OCCAR. These armament companies have followed the same trends as their civilian corporate counterparts, of including heavy adoption of sub-contracting to obtain components and raw materials needed to manufacture weapon systems. Neoliberal globalisation has changed supply chains globally, and defence companies are no exception. These companies adopted a ‘just-in-time’ production culture,[8] reducing or eliminating material and parts stockpiles to reduce overheads costs for the final product. Strategic independence, once fundamental for our military supply, has been degraded in favour of maximising business competitiveness in a globalised world. Put plainly, maximising profits has taken precedence over securing indigenous supply chains in support of national defence.

To the EU’s credit, in recent years it has been working to develop a joint industrial policy.[9] Recently, the European Defence Agency (EDA) examined these overarching concerns and published the Code of Conduct on Procurement, Offsets and Good Practices in the Supply Chain. Such policies are needed, as many EU countries cannot aspire to unilaterally establish independent indigenous military supply chains, in the same way as the US is attempting to do. Individually, their size, available natural resources, and industrial capacity prevent such autonomy, but the EU as a whole can achieve such an objective, thus enhancing the robustness and independence of its Common Security and Defence Policy.

Unfortunately, the Code of Conduct merely provides guidelines for the member states; there is no obligation to comply, and it thus fails to implement a true EU-wide industrial policy. To exacerbate matters, member states use Article 346 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU),[10] to exempt themselves from complying with existing procurement rules. This leaves the security of their supply chains in the hands of contracting companies, with no corresponding national legislation in most cases obliging these companies to assume legal responsibilities for military procurement.

US and European Companies in China’s Hands

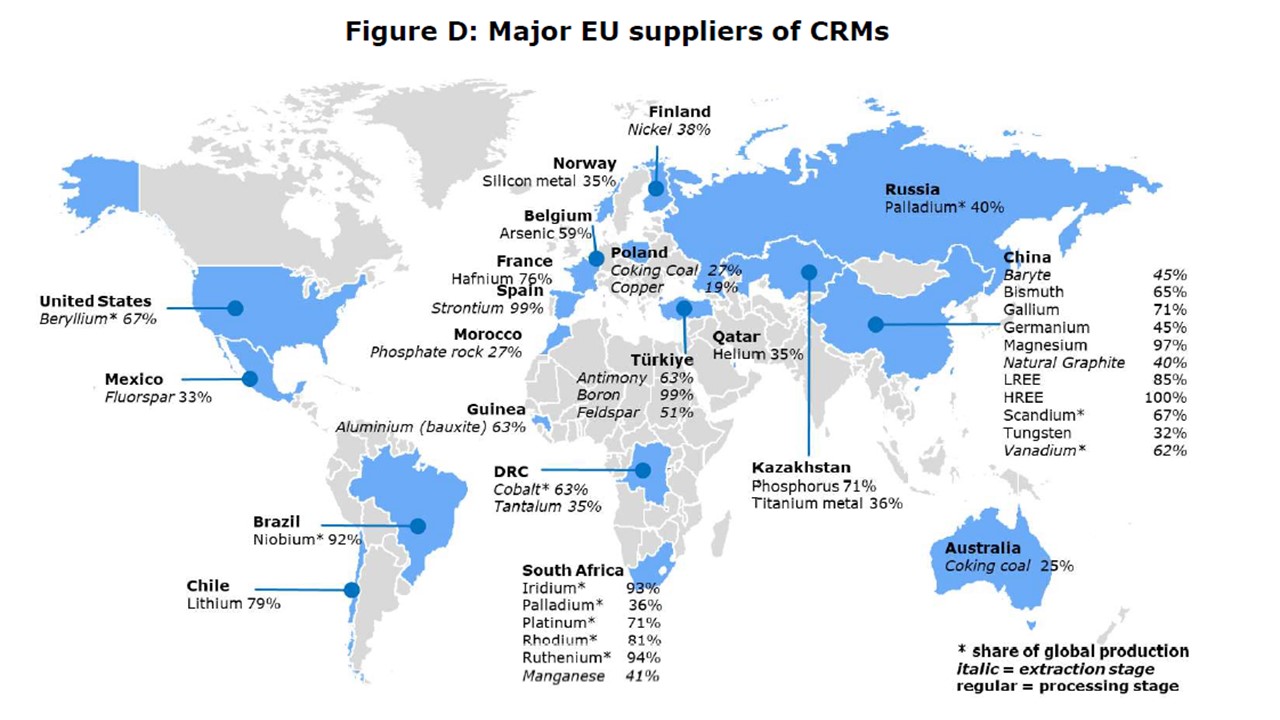

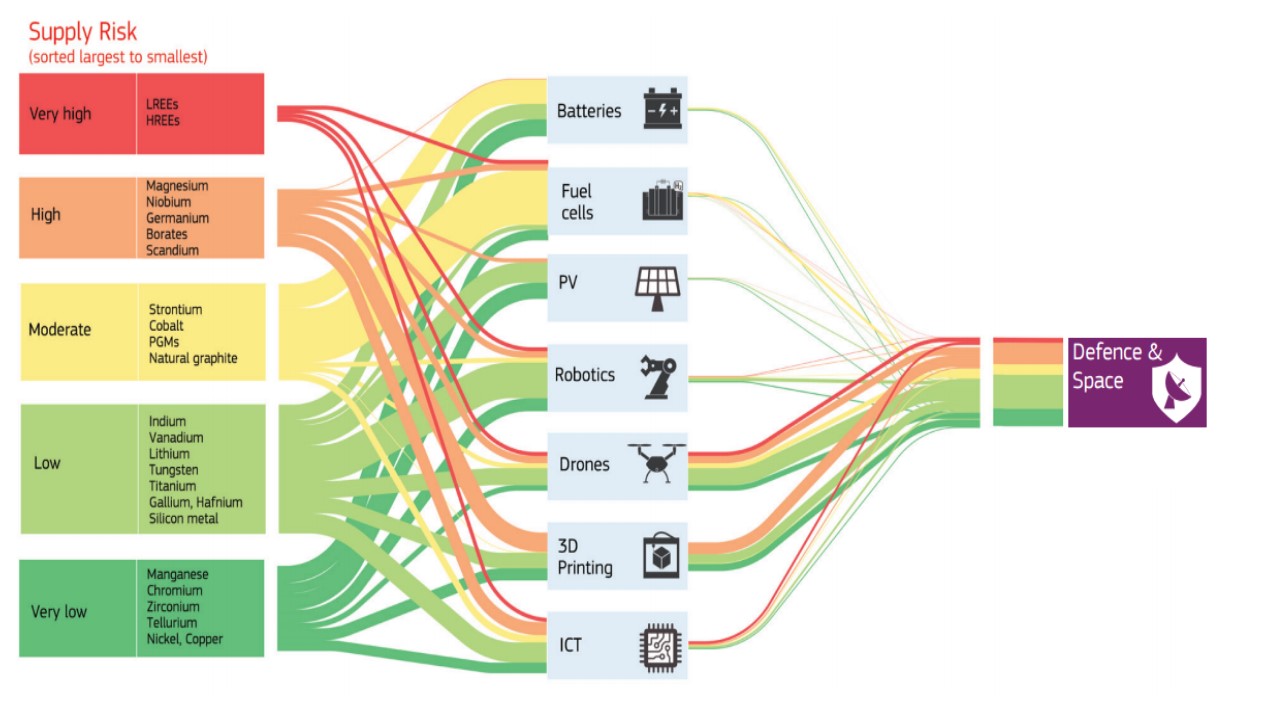

The current supply chain situation within the EU, where no mandatory laws exist, either at interstate or national levels regarding critical materials needed for national defence, creates a significant vulnerability for its members’ militaries. Even more worrisome, the European Commission itself forecasts a high risk of critical material shortages, and a very high risk of a rare earth shortages by 2025[11]. But the situation goes from worrying to alarming when one notes that many of these materials are in the hands of China. It is no coincidence that today the elements cobalt, lithium, manganese, tungsten, antimony, bismuth, graphite, fluorspar and germanium are under a Chinese monopoly, in either the amount extracted or processed, with China providing more than 50% of the global total. Concerning the EU, China is its largest supplier with a 90% share[12] and if we refer to heavy rare earths that are present in many of our most technologically-advanced weapon systems, this monopoly reaches almost 100% of the metals. China is well aware that Western strategic autonomy is in its hands.

The Chinese sanctions imposed on Lockheed Martin and Raytheon could represent just the tip of the iceberg. A hypothetical future projection of China’s past threats or diplomatic uses of rare earths suggests that it will sanction any other defence companies that could directly or indirectly jeopardise its security. These would be, for example, any other companies selling arms to any country with which China is in conflict. Imagine the implications that this ‘weapon’ would have in the Ukraine conflict if China decided to clearly take Russia’s side. Specific companies or countries as a whole could face limitations, interruptions or bans on their supply of rare earths and other rare metals. Finally, it is the Chinese Government which dictates the threshold of sensitivity that triggers a rare earth blockade.

On the US side, in a recent edition of China’s Modern Defence Technology journal, Chinese researchers denounced the enormous military potential of SpaceX’s Starlink and called for the development of capabilities to monitor, deactivate, or destroy this constellation of low-Earth orbit satellites. Among other concerns, scientists pointed out the ability of such satellite networks to detect their hypersonic missiles, and exponentially increase the data transmission of their aircraft such as the F-35 and their drones. They also argued that this network had already put their satellites in danger of collision in July and October 2021, a fact that was denounced by the Chinese Government before the UN.

The ban on the export and use of rare earths could be the perfect weapon to disable the Starlink satellite network or similar European networks, whose military utility has already been established as a result of the war in Ukraine. Given that sanctions constitute a low-cost, low-threat alternative to physically destroying satellites, as well as obviating the hazard from debris posed by destroyed hostile satellites to friendly satellites, they offer China the ability to curtail or even effectively negate Western satellite capabilities in the medium term. It would be an action within the so-called grey zone since it does not imply the use of force and as such would avoid an escalation towards a conventional military confrontation.

Another theoretical example, in this case European, would be the French company Dassault Aviation[13] and the European company Airbus[14], which have sold both Rafale fighter and transport aircraft (A400M and C295) to India and Indonesia, respectively. In some cases, these agreements involve not only the sale but also a certain transfer of technology, since in the final stages of the procurement programmes the aircraft are produced in the buyer country. A rare earth ban against these countries would prevent them from producing sufficient quantities of avionics and mechanical parts needed to complete construction.

These theoretical examples are not at all far-fetched if we look at the retaliation provoked by simple balloon destruction and growing geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific region. We should also recall that China has had a border dispute with India for years. It also actively claims, through its fishing militia, part of Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Natuna Sea, and in late 2019 there was even an incident that resulted in military action[15]. Furthermore, the tensions generated by Chinese aspirations to reconquer Taiwan have led to the February 2022 announcement of initial sanctions by Beijing against American companies Lockheed Martin and Raytheon for the sale of weapons to Taipei. Following the same argument, China could also issue sanctions against Dassault, and thus against France for selling armaments to other countries that threaten its security or national interests.

This example could be extended to other European weapon system manufacturers, such as frigate manufacturers, which have a growing presence in the Indo-Pacific, and which is set to grow even further. This is envisaged in the ‘EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific’[16] document published in April 2021. It states the EU’s intention to “…cooperate with the navies of its partners, and develop their capabilities where appropriate, to establish global vigilance in the interests of maritime security and freedom of navigation, in accordance with international law…”. Many modern frigates incorporate more than 1.5 tonnes of rare earths, but the case of the Rafale fighter aircraft is particularly significant, as it can carry nuclear weapons. The Rafale constitutes, along with strategic nuclear submarines, a key vector in power projection and a cornerstone of the French national defence strategy, based on nuclear deterrence that depends on various critical materials, including rare earths.

Strategic Insolvency in the Terrible Twenties

The impacts of sanctions are not limited to a potential future conflict in the Indo-Pacific. Another potential scenario is a shift in China’s policy of support for Russia in its ongoing war against Ukraine. Western countries imposing sanctions on China[17] could end up facing retaliatory measures such as a ban on exports of rare earths by the Chinese Government.

As geopolitical tensions increase, the EU, Japan and Australia appear to be ratifying their alignment with US foreign and security policy. As a result, the hitherto limited exchanges of sanctions between these countries and China could expand and affect other areas, such as critical materials needed for the defence sector. The Western defence sector’s dependence on Chinese rare earths throughout its supply chain represents a bitter enemy to its strategic autonomy both at the national level and within the framework of its Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and NATO alliance. It limits the West’s technological sovereignty and may in the future be a limiting factor in its ability to respond to crises and sustain military operations.

This current period offers a window of opportunity for those enemies of Western countries who, aware of their weaknesses, could take advantage of them to challenge the West and achieve their objectives. Taiwan, the Senkaku Islands and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the South China Sea, and the Spratly Islands (claimed from the Philippines) are all at stake, but so too is the Arctic Circle, the ocean floor, or even outer space, in a critical period characterised by Western strategic insolvency.

Not without reason, this decade has already been dubbed by many defence analysts as ‘the terrible twenties’ due to manufacturing and supply chain problems.[18] National-scale logistics have always constituted the life force of national defence, without which, international security vanishes as well. For better or worse, modern militaries are dependent on private companies for procurement and outfitting, and no Western defence company will voluntarily operate at a loss to secure either our independence from China, or the required war reserves for our militaries. This means Western governments bear the responsibility for overhauling industrial bases and supply systems in record time, starting with the most critical components and materials, especially rare earths.

Many EU hopes were pinned on the Critical Raw Materials Act published on 16 March 2023. However, the lack of strong measures in this new regulation fails to meet the needs of domestic production and self-supply of critical materials for EU defence industries. It seems that unless there is a diplomatic disagreement with China, the EU prefers not to clearly take interventionist and forceful measures against its economies. The problem is that if it has just taken China 10–15 years to take over the rare earth supply chain, the EU will need the same time to take it back. The EU’s reaction time is out of step with the pace of de-globalisation and the current geopolitical landscape. Catching up will require a significant shift in gear by its member states.

Juan M. Chomón Pérez and Craig Hymel

[1] Chang W. and McCarthy S., ¨China sanctions Lockheed, Raytheon after vowing to retaliate against US restrictions¨ Feb. 2023 https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/16/business/china-sanctions-lockheed-raytheon-hnk-intl/index.html

[2] Borken, J., “The Crimes and Punishment of I.G. Farben,” Barnes and Noble, 1997. 2nd Edition.

5 Caruana, L., & Rockoff, H., ¨A Wolfram in Sheep’s Clothing: Economic Warfare in Spain, 1940-1944¨,2003, The Journal of Economic History, 63(1), 100-126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3132496

[4] United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, ¨Stockpile and Accessibility of Strategic and Critical Materials to the United States in Time of War¨, 1953, https://books.google.de/books?id=t6gqTKrMEq4C&dq=stockpile+and+accessibility+of+strategic+and+critical+materials+to+the+united+States+in+time+of+war&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

[5] The White House, ¨FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force to Address Short-Term Supply Chain Discontinuities¨, Jun. 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/08/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-supply-chain-disruptions-task-force-to-address-short-term-supply-chain-discontinuities/.

[6] Bailey Grasso, V. “The Berry Amendment: Requiring Defence Procurement to Come from Domestic Sources,” Congressional Research Service, 24 February 2014.

[7] Shiffman J., Shalal-Esa A., ¨Exclusive: U.S. waived laws to keep F-35 on track with China-made parts¨, Jun 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lockheed-f35-idUSBREA020VA20140103

[8] Government of Canada, ¨The Trouble with JIT in Military Operations: a Review¨, Jan. 2022¨, https://www.canada.ca/en/army/services/line-sight/articles/2022/01/the-trouble-with-jit-in-military-operations-a-review.html.

[9] Evidenced by Directive 2009/81/EC on defence procurement and Directive 2009/43/EC on transfers of products related to the European defence market. In addition, the European Defence Agency subsequently published the Code of Conduct on Procurement and the Code of Best Practice in the Supply Chain, as well as the Code of Conduct on Offsets.

[10] Randazzo V., ¨Article 346 and the qualified application of EU law to defence¨, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Jul. 2014, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief_22_Article_346.pdf

[11] KU Leuven University, echoing earlier publications by the International Energy Association, quantifies between 7 and 26 times the increase in current rare earth consumption needed by 2050 to reach the EU’s climate targets. ¨Study quantifies metal supplies needed to reach EU’s climate neutrality goal¨, Apr. 2022, https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/949848

[12] European Raw Materials Alliance, ¨Ensuring access to the raw materials for the European Green Deal: A European Call for Action¨, Sep. 2021, https://erma.eu/european-call-for-action/.

[13] ¨Dassault welcomes India’s purchase of 36 Rafale¨ and ¨Indonesia buys Rafale¨, https://www.dassault-aviation.com/, accessed April 25, 2022.

[14] ¨India formalizes purchase of 56 Airbus C295 aircraft¨ and ¨Indonesian Defence Ministry orders two Airbus A400Ms¨, 2021, https://www.airbus.com/, accessed 25 April 2022.

[15] Laksmana E., ¨Indonesia’s response to China’s incursions in North Natuna Sea unsatisfactory: Indonesian¨, Dec. 2021, academichttps://www.thinkchina.sg/indonesias-response-chinas-incursions-north-natuna-sea-unsatisfactory-indonesian-academic.

[16] European External Action Service, ¨EU Strategy for Cooperation in The Indo-Pacific¨, Feb. 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-indo-pacific_factsheet_2022-02_0.pdf.

[17] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/31/eu-leaders-urged-to-be-tough-on-china-if-it-supports-russia-war-in-ukraine

[18] Mackenzie Eaglen with Hallie Coyne, The 2020s Tri-Service Modernization Crunch (Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, March 2021), p. 1, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-2020s-Tri-Service-Modernization-Crunch-1.pdf?x91208.