Malaysia’s regional defence environment is characterised by a complex and dynamic security landscape, with a range of security threats, including border disputes, piracy, and terrorism. The country’s strategic location in Southeast Asia has also made it an important partner in regional security cooperation efforts.

For the European defence industry Malaysia was once one of their favourite foreign defence markets, it offered good programmes to try and win. Equally as important was the fact that Malaysia was politically stable, therefore it was possible to build long-term relationships with key decision makers. This political stability also provided the basis for long-term defence acquisition planning, potentially allowing customers and suppliers to work together to generate satisfactory procurement outcomes.

Over time though, this ‘idealised’ defence procurement structure changed. The relatively benign system that had been so satisfactory in the past became much more competitive. The political stability that had been so highly prized in Malaysia started to unravel, with political factionalism becoming more and more visible. It should be noted that Malaysia’s economy continued to develop, reflecting the better financial performance and higher sophistication of many of the national economies of Southeast Asia. Economic growth meant that political leaders could set ambitious development goals, geared towards further developing the national economy and improving the economic outcomes and social opportunities available to Malaysia’s population.

It is clear that Malaysia’s political and economic leaders have transformed the country over the past few decades, and efforts to diversify the economy from reliance on oil, raw materials and agriculture have also delivered benefits. However, once the national political environment became more combative, this tended to overshadow economic and social development. To this one must also add the economic impact of COVID and the ongoing costs of dealing with that crisis.

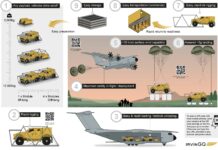

Credit: USAF

Strategic Environment

Key to understanding the broader Malaysian defence environment comes from an analysis of the main strategic, economic and socio-political factors in Malaysia. Malaysia is located in a critical position in Southeast Asia, to the west of the Malay peninsula you have the Strait of Malacca, this is of major importance in that it has been described as the second-largest oil supply choke point in the world, after the Strait of Hormuz at the base of the Gulf. The Strait of Malacca is one of the major global trade arteries, if free passage of shipping could not be assured there would be significant global economic impact. Equally, Malaysia would accrue significant economic damage in these circumstances. Piracy remains an issue in the Strait of Malacca, albeit a manageable issue at this point.

Malaysia has a number of regional maritime border disputes with neighbouring states, but these are subject to negotiation and do not have a strategic impact. What does though are the competing maritime claims to the Spratly Islands area in the South China Sea. Here Malaysian territorial and adjacent Extended Economic Zone (EEZ) claims, as well as those of Brunei, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam come into conflict with those of China. Moreover, China has made it clear that it regards the Spratly Islands as a key strategic area, and it continues to expand its presence in this area.

The Spratly Islands area is another major maritime artery, the ability to block or interdict this artery would be strategically beneficial in a regional context. There are also strong economic motives to control the area, there are rich fishing grounds and potentially large offshore oil resources that are extractable. The disputed nature of the Spratly Islands area has long been seen as having the potential to trigger a regional conflict.

Another area of concern for Malaysian security planners is along the northern border with Thailand. The three southern Thai provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat are the primary location of an ethnic Malay nationalist insurgency, which in its current incarnation has continued for some 18 years. To counter the insurgency, Thailand has deployed substantial numbers of military, paramilitary and police personnel in the three provinces. The Thai government has opened ongoing negotiations with various insurgent groups, but no end to the insurgency has resulted thus far.

From a Malaysian perspective, the primary mission is to avoid any overspill of violence from southern Thailand into northern Malaysia. Obviously there is sympathy for an ethnic Malay insurgency, although the preference would be for a negotiated end to the insurgency and a long-term political solution acceptable to all parties to the conflict.

Political Change

In terms of Malaysia’s political stability, central to this was the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), effectively ‘the’ political party of the majority Malay population and thus the dominant political force in the country. It would then form a coalition with ethnic Chinese and Indian parties as junior partners, to provide a representative government across the major ethnic groups in Malaysia. Initially, the coalition was called the Alliance, later it become the Barisan Nasional (BN). The UMNO + BN would provide the Malaysian government from 1957 through to May 2018, in that time there would be six different Prime Ministers. Since May 2018 there have been four different Prime Ministers, representing four different political coalitions.

The current Prime Minister of Malaysia is Anwar Ibrahim, who won the November 2022 election at the head of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) or Alliance of Hope coalition. By contrast, in that same election UMNO/BN had their worst ever result. Ironically Anwar had once been a leading member of UMNO, but his fall from grace in that organisation would see him imprisoned twice after politically-inspired prosecutions. The fate of Anwar would be the point where politics in Malaysia went from stability to something far more combative.

In 2020 former Prime Minister Najib Razak (Prime Minister from 2009 to 2018) was sentenced to 12 years in jail for corruption, with appeals against this verdict being lost in August 2022. In March of 2023, former Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin (in office March 2020 to August 2021) was arrested on charges of bribery and money laundering related to COVID spending. Muhyiddin has been a political rival of Anwar’s for years and there is known to be considerable animosity between the two, meaning that any corruption charges must be clearly provable otherwise this will be seen as a political prosecution.

Credit: US Navy

The Economy

If the Anwar government is to survive in office it must deliver on completing the recovery from COVID and improving the economy. Although it is politically more progressive than previous governments, it needs to get the economy right or it will fail. Any hopes of significant defence procurement in Malaysia also depend on an improvement in the economic situation, although the government does not appear well disposed towards defence and there are problems to confront regarding current defence programmes.

The first test as to how the Anwar government is viewed by the electorate will come in the state-level elections in July 2023. There are 13 states in Malaysia, and these local elections have no real impact on the government as such, but they will act as a virtual referendum on the performance of the government. Remember that the government is based on a coalition and should the state election results reflect major dissatisfaction with the government, some of their parliamentary support could evaporate and that might set the scene for the government to fall.

The national budget, released by the government in late February this year, really needs to deliver. Key elements were an increase in taxes on the wealthy and an increase in subsidies to help the lower paid. The government has admitted that it must reduce the national debt, officially this is running at USD 270.6 Bn currently, equivalent to 62% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), up from 60.4% last year. However, if other government liabilities are included, the national debt stands at USD 338.2 Bn or 81% of GDP. Currently 16% of government revenue goes on paying debt interest. The aim is to get the official national debt down to 55% of GDP, essentially where it was prior to Covid.

Subsidies on petrol, diesel, Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG), cooking oil, flour and electricity, saw the government spend USD 18 Bn in 2022. Reductions in commodity prices are expected to see the subsidy financial burden reduced to USD 14.4 Bn this year. Unfortunately, reductions in commodity prices also hurt the revenue situation of the Malaysian government. The main non-taxation source of revenue for the government are dividends from the state oil company Petronas, in 2022 they received of USD 11.2 Bn from this source. Reduced oil prices mean a reduced Petronas payment in 2023, expected to reach only USD 9 Bn.

The Anwar government needs strong GDP growth in the second quarter of this year, it needs the subsidy regime to satisfy the majority of the electorate and it needs to pay down the national debt, to reduce the interest payment burden on the national budget. If they can achieve economic stabilisation, without losing popularity, the government is likely to remain in office. A stable economy also means that more public spending is possible, and this could potentially see more money for defence procurement.

Defence Programmes and Possibilities

For all of the negativity surrounding defence procurement in Malaysia, there was a positive development on 24 February 2023, when Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) announced that it had won a USD 920 M contract covering the supply of 18 FA-50 aircraft, with deliveries to begin in 2026. This acquisition will go some way to meeting the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) requirement, 36 aircraft were due to be acquired in total and will eventually replace the BAE Systems Hawk in RMAF service. Aircraft evaluated for the LCA requirement included the Tejas from India and the JF-17 from Pakistan. There are also reports that the RMAF will receive a new long-range air defence radar this year.

Credit: KAI

Deliveries of three new Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) for the RMAF commenced in August 2022 with the arrival of the first CN-235. This capability was acquired via the US Navy Building Partner Capacity programme. Other outstanding RMAF requirements included a multirole combat aircraft, with Rafale, Eurofighter and Gripen amongst others being considered. This is clearly an expensive programme and potentially controversial in the current environment, hence no decision is expected in the short-term. The RMAF is also looking to acquire an AEW&C capability, new helicopters and an enhanced UAV capability.

Over the years the Malaysian government has looked to develop the Malaysian economy by moving into more sophisticated areas, it believed that defence procurement could aid that economic development, via the transfer of technology and offset programmes. It also believed that the local production of defence equipment could create employment and provide for the sustainment of said equipment throughout its service life. In consequence, defence procurement shifted from in principle finding the best and most affordable solution for the Malaysian military, to political and economic development factors becoming a key part of the procurement process. As such, procurement became vastly more difficult.

A good example of this is the fate of a number of programmes for the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN). As previously discussed, the strategic situation of Malaysia demands that it has an effective maritime capability. To meet this requirement in the 1990s the RMN started the New Generation Patrol Vessel (NGPV) programme, this was won in 1997 by Blohm + Voss with the MEKO 100 design. At that time the RMN objective was to acquire 27 NGPV, but the first order for the NGPV covered only six units, to be known as the Kedah class, four of which were to be built in Malaysia by PSC-Naval Dockyard (PSC-ND).

There were management and financial problems at PSC-ND that delayed the NGPV programme, as a result Boustead Heavy Industries (BHIC) were invited by the government to take control of PSC-ND and resolve the situation, which they eventually did. As a result BHIC and their subsidiary Boustead Naval Shipyard (BNS), were in the leading position as regards the provision of shipbuilding and dockyard services to the RMN. However, with the commissioning of KD Selangor, the sixth and last unit in December 2010, the NGPV programme came to an end.

The RMN then developed a transformation plan, commonly known as 15-to-5, under the plan the 15 ship classes in RMN service would be reduced to five, the five being: submarines, Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), Littoral Mission Ship (LMS), Multi-Role Support Ship (MSS) and NGPV. The RMN already had two Scorpene class submarines, now the plan was to add two more. As regards the NGPV, the plan was to acquire 12 more units potentially built to an improved Kedah class (MEKO 100) design. The MRSS is an LPD-like capability, for disaster relief and other missions, with up to three units to be acquired. For the LMS requirement, effectively an OPV/corvette hybrid, 18 units would be required. At the top end of the performance spectrum comes the LCS, effectively a frigate-type capability, with 12 units being required.

Progress has been made on implementing this transformation plan, in 2016 a contract was signed for four LMS, two of which would be built in China and two to be built in Malaysia at BNS. Then in 2019 it was decided that all four units would be built in China and the resulting Keris class were commissioned into the RMN between January 2020 and January 2022. This was the first time Malaysia awarded a major defence programme to China.

However, a second batch of three LMS planned by the RMN will likely be built to a European design. As regards the MRSS programme, the RMN hopes to progress this in 2024 after receiving a funding allocation.

Credit: US Navy

The most significant and currently the most problematic RMN programme is the LCS. Here the Naval Group Gowind 2500 design was chosen as the basis for the LCS and by 2014 the programme had evolved to the point where six LCS would be built by BNS in Malaysia.

These units would be known as the Maharaja Lela class, the lead ship was to have been delivered to the RMN in April 2019, with the last unit to be delivered to the RMN in June 2023.

There have been major problems at BNS, KD Maharaja Lela was launched in August 2017, and expected delivery to the RMN is now due in the third-quarter of 2024, though there are suggestions that 2025 is more likely. The programme is now due to be complete with the delivery of the final unit in 2028. On top of these delays, the programme has been reduced in scope to cover only five instead of six LCS vessels. Despite the programme being in crisis, cancellation was never considered due to the implications for the workforce at BNS. The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of the Malaysian Parliament issued a highly critical report on the LCS programme in August 2022.

What happens next with the LCS programme depends on the Anwar government, at best they can blame previous administrations and BNS with incompetence, at worst with malfeasance. In the meantime the RMN finds itself with an incomplete force structure plan and no firm guarantee when it will receive all five LCSs. Beyond that, it is clear that the Malaysian procurement system needs reform.

David Saw