This article explores regional naval shipyard and construction trends and developments across three regions in Europe. It concludes with a brief consideration of longer term trends and implications for naval industry in Europe as the continent’s security situation continues to change. We draw our data from AMI International’s proprietary content used in their naval market forecasting products.

The dramatic changes in Europe’s security environment due to the war in Ukraine continue to reshape all aspects of military planning and expenditure in the region. While much attention has been focused on the impact of the Ukraine conflict in the ground and air domains, it has also affected naval programmes and infrastructure in Europe.

Our regional review of current and forecast ship construction programmes starts in the Baltic region (Poland, Finland, Sweden and Denmark). It specifically identifies local shipyards engaged in or capable of naval construction in those countries. Next, we review similar information for Western Europe (Germany, France and the United Kingdom), followed by Mediterranean Europe (Spain, Italy Greece and Turkey). We also include some general observations on prospects for European naval shipbuilding in the coming decade.

Overview

AMI’s 20 year forecasts (Table 1A and Table 1B) below presents a ‘pre-war’ snapshot of European naval shipbuilding. Taken together, these two European regions contribute about 30% of global forecasted new ship acquisitions worldwide over the next two decades, as measured by acquisition value. These regional forecasts have remained steady over the past decade, despite the deterioration of the security environment in Europe, accelerated by Russia’s 2014 annexation of the Crimea and, now, other parts of Ukraine.

| Table 1A: NATO (less United States) | ||||

| Total No. of Projects | In Progress | Planned | Total Value | Total Build (2022-41) |

| 153 | 66 | 72 | USD 287,562.12 M | 798 |

| Table 1B: Non-NATO Europe (led by Sweden and Finland) | ||||

| Total No. of Projects | In Progress | Planned | Total Value | Total Build (2022-41) |

| 22 | 11 | 7 | USD 10,429.00 M | 104 |

Table 2 below shows the five countries in Europe with the highest total forecasted new construction naval spending, representing just over 50% of the entire forecast for NATO (excluding the United States) Non-European NATO member Canada, driven by its new frigate programme, accounts for another 25% of total NATO forecasted expenditures, all measured in USD M.

| Table 2: Five European Countries with Highest Total Forecast Naval Expenditure 2022-2042 | |

| Country | Expenditure |

| United Kingdom | USD 61,396 M |

| France | USD 29,080 M |

| Germany | USD 24,296 M |

| Italy | USD 23,676 M |

| Turkey | USD 19,764 M |

| Total | USD 158,212 M |

The war in Ukraine has permanently altered the continent’s security landscape – notably with the prospective accession of Sweden and Finland into NATO – and prompted many country-level re-evaluations of planned defence spending. However, prospects for marked increases in European naval shipbuilding currently remain aspirational. Any substantive increase in new ship acquisitions from Europe’s naval builders would have long lead times and programme durations. Accordingly, any uplift in new ship acquisitions driven by the Russo-Ukraine war are not expected to result in changes to existing forecasts for at least another one to two years. Moreover, any such increases will be complicated by the inflationary and recessionary forces at work on the region’s economies, further clouding the prospects for higher naval acquisition budgets.

Hence our review of the impact of the Ukraine conflict on naval shipbuilding to date shows more in the way of continuity with historical patterns than change. Underinvestment in naval capability continues: a factor consistent with overall declines in naval ship purchases – and increasing costs of ships and systems – that have marked the post-Cold War period. European shipbuilding programmes continue to suffer delays and postponements, due in part to continued constraints on European defence spending, as well as the competing pressures to prioritise the air, missile and ground capabilities that have been more visible in the Ukraine conflict. On the plus side of the naval shipbuilding ledger, selective progress on programmes such as the Netherland’s future submarine acquisition and increased naval spending by Eastern European countries (corvettes for Ukraine and Romania, frigates for Poland) offer some encouragement for future business growth among Europe’s naval shipyards.

We note other recent signals of future shifts away from current patterns of (low) naval budgeting and building in Europe. These include:

- Denmark committing to revised defence policy and shipbuilding infrastructure plans, with new investments (a total of over USD 5 Bn has been mentioned) for shipbuilding and new ships.

- German company TKMS acquiring new facilities to improve capacity.

- Finland reportedly raising its 2023 defence budget by 20%, potentially supporting the realisation of agreed naval programmes.

- Italy continuing a major fleet renewal that will benefit Fincantieri’s Italian yards.

- Turkey building ‘Milgem’ corvettes for export to Pakistan and the United Kingdom, as well as promoting other naval vessels and equipment for overseas sale. Domestically, the new amphibious assault ship TCG Anadolu is slated for commissioning into Turkish service sometime in the first half of 2023.

- The United Kingdom gaining renewed naval export momentum, as evidenced by Babcock’s sale of the Arrowhead 140 design to Indonesia and its selection for the Polish frigate programme. This follows on from BAE Systems’ success with the Global Combat Ship in Australia and Canada.

- Continued European collaboration on new naval programmes, including the engagement of Fincantieri, Naval Group and Navantia in the European Patrol Corvette (EPC) and the cooperation between Germany and Norway in procuring new submarines.

The Baltic Region

Baltic countries generally have small but capable naval ship construction infrastructure. Most have a single primary builder, and other secondary yards for niche construction, as well as repair and modernisation work. Governments in these countries generally award contracts that ensure local yards are primary builders or otherwise have significant workshare in new naval construction. One exception is Denmark, where there is currently no local facility capable of specialised naval ship construction following the 2009 closure of Odense Steel Shipyard. The smaller Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania also have significant capacity to build and repair larger commercial ships, but are not currently engaged in naval construction. One major exception is Baltic Workboats Estonia, which is a builder and exporter of patrol boats.

Poland

AMI forecasts five new construction ship and submarine programmes. The two shipyards that engage in naval ship construction are involved in the current MCMV building programme building and the recently awarded frigate programme, as summarised in Table 3.

| Table 3: Poland | ||

| Project | Status | Local Yards Involved |

| ‘Kormoran II’ Class MCMV | Building | Remontowa Shipbuilding & PGZ Naval Shipyard |

| Maritime Border Guard 70 M OPV | Building | None (built by Socarenam, France) |

| ‘Miecznik’ Class Frigate | Awarded | PGZ Naval Shipyard & Remontowa Shipbuilding [1] |

| Hydrographic Survey Ship (AGS) | Planned | PGZ Naval Shipyard & Remontowa Shipbuilding [2] |

| Future Submarine (‘Orka’ Project) | Planned | To be determined |

| 1. With design assistance from Babcock International | ||

| 2. With design assistance from a foreign supplier |

Finland

AMI forecasts three new construction ship programmes set out in Table 4. The country’s Rauma shipyard is its primary facility for construction of more complex naval ships. Finland does not currently operate submarines. Three other shipyards – Marine Alutech Oy Abare, Meyer Turku Oy, and Helsinki Shipyard – are capable of building smaller vessels, as well as commercial platforms.

| Table 4: Finland | ||

| Project | Status | Local Yards Involved |

| Turva Class OPV (Batch 2) | Awarded | Meyer Turku Oy |

| Pohjanmaa Class Corvette | Awarded | Rauma Marine Constructions |

| Inshore Minesweeper (MSI) | Planned | TBD (will be a local shipyard) |

Sweden

AMI forecasts seven new construction ship and submarine programmes set out in Table 5. The county’s primary naval shipyard is Saab Kockums, while a second yard, Swede Ship Marine AB, can perform work on smaller patrol craft and amphibious vessels.

| Table 5: Sweden | ||

| Project | Status | Local Yards Involved |

| Artemis SIGINT Vessel | Building | Saab Kockums (final outfitting) |

| Blekinge (A26) Class Submarine | Building | Saab Kockums |

| Coast Guard KBV 230 PV | Awarded | None, contracted to Damen [1] |

| Future Surface Combatant (Visby II) | Planned | Saab Kockums |

| Future MCMV | Planned | Saab Kockums |

| Future Logistics Ship | Planned | TBD (likely Saab Kockums) |

| Next Generation Submarine (UB30) | Planned | Saab Kockums |

| 1. Maintenance will be carried out by Damen Oskarshamnsvarvet |

Denmark:

AMI forecasts three new construction ship and craft programmes. The country’s planned 800 tonne environmental protection vessel and future 3,000 tonne OPV are expected to be designed and built in Denmark at one of the country’s existing commercial shipyards, perhaps with investments to enable the selected yard to meet naval-related construction standards. Smaller patrol boats are also expected to be allocated to a local yard, such as Søby Vaerft.

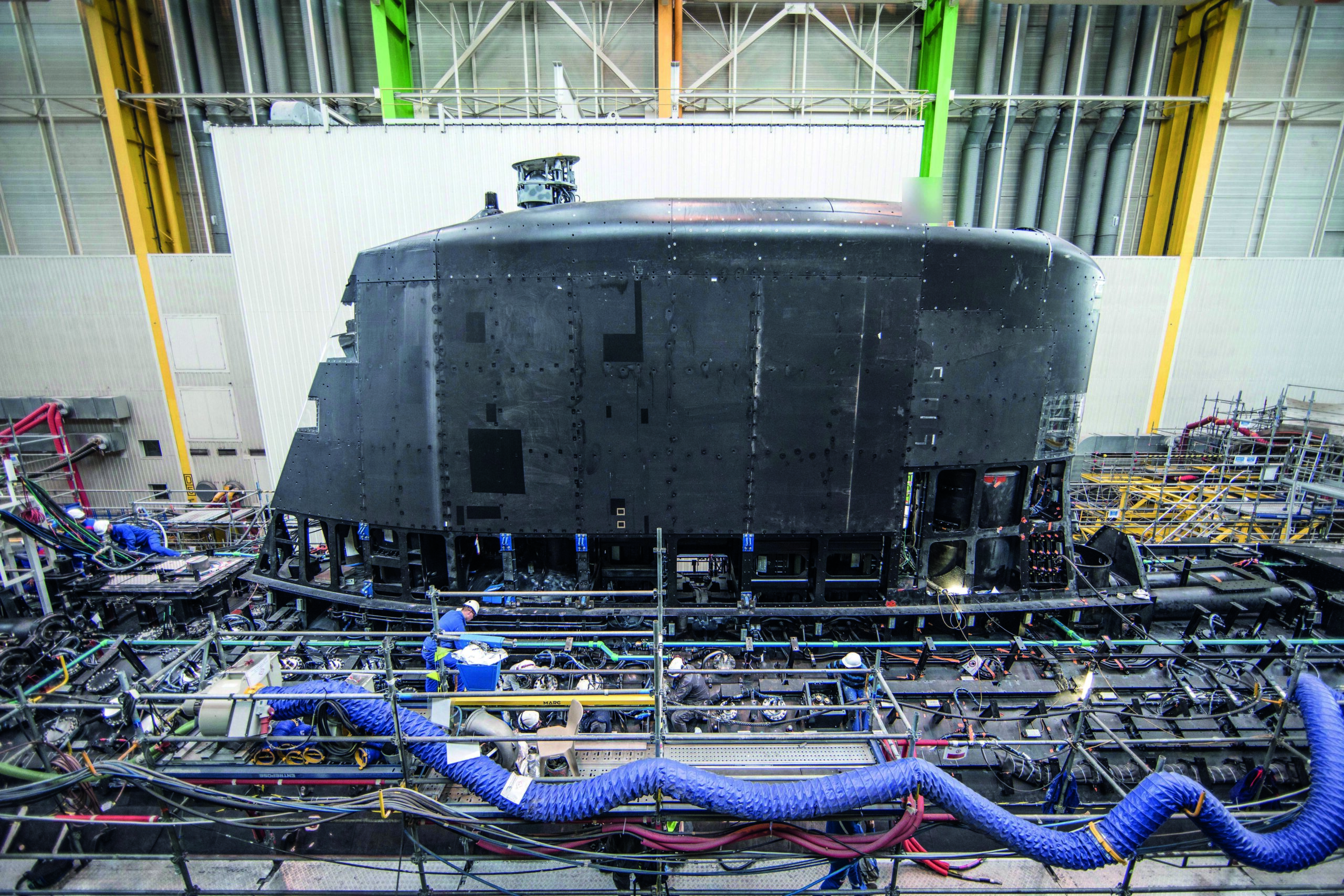

Credit: Naval Group

Western Europe

The UK, France and Germany are Europe’s leading naval shipbuilding countries, with industry supporting a steady domestic demand driven by the region’s largest and most capable navies, as well as serving export markets around the world. Each country fields a layered naval shipbuilding infrastructure, led by large, multi-purpose builders of a variety of surface ship types, robust mid-tier yards, and specialised builders of vessels such as submarines, mine warfare ships, and smaller fast combatants. The UK and France also maintain robust nuclear submarine construction facilities. Each of the three countries benefit from strong naval combat systems, sensors and weapon companies, which supports ship-system integration across a number of major ship programmes.

AMI’s 20-year forecasts of future naval ship acquisitions for each of these countries are shown in Table 6 below. This data highlights that all three nations are acquiring new ships to maintain a balanced portfolio of capability across mission types, although Germany is significantly more weighted to replacing surface combatant and auxiliary types compared to the UK and France. The UK’s replacement strategic submarine (SSBN) programme skews that country’s spending on submarines and is moving dramatically upward; without that expenditure, British future naval acquisition by ship type, distribution and cost would be closer to its French peer.

The shipbuilding infrastructures that will delivery these new ships are scaled for domestic markets that have slowly but steadily declined over the past three decades, making growth in export opportunities and diversification into other markets increasingly vital to sustaining their businesses to local shipyards. Scaled to this market structure and demand, the region’s builder yards, operating as publicly traded business entities, would require some lead time to scale up (in physical plant and human resources) in response to increasing demand for naval ships. In other words, there is limited spare capacity to significantly increase naval building, even if financial resources were already available.

| Table 6: Western Europe (2022-42) | |||||||

| Country | Surface | Submarines | Patrol | MCMV | Amphibious | Aux | Total |

| UK | |||||||

| Programmes | 4 (DDG/FFG) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| New Hulls | 14 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 28 |

| Acquisition Cost | 27,095 | 31,2 | 0 | 0 | 700 | 2,401 | 61,396 |

| France | |||||||

| Programmes | 3 (CV/FFG) | 2 | 3 (OPV/PV) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| New Hulls | 15 | 7 | 24 | 11 | 12 | 4 | 72 |

| Acquisition Cost | 13,7 | 10,9 | 1,45 | 950 | 480 | 1,6 | 29,08 |

| Germany | |||||||

| Programmes | 3 (DDG/FFL) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| New Hulls | 17 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 34 |

| Acquisition Cost | 17,72 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3,576 | 24,296 |

| Note: Costs in USD M |

Additionally, the experience level of naval shipbuilders in all three countries is reducing, as the generation that built and sustained the larger number of Cold War-era naval platforms has retired, or will do so over the coming decade. Their replacements are fewer in number, due to reduced domestic demand and fluctuating export orders (many of which are increasingly built in the country ordering the new ships rather than in European yards). This structural, human resource constraint could also make it difficult for Northern European shipyards to increase production beyond current levels.

Navies in the Northern Europe region are recognising some of the potential risks of their current ‘peacetime’ naval industry configuration. In November, Germany was among six countries entering a ‘Northern Naval Shipbuilding Cooperation (NNSC) Initiative’. Other countries participating in the initiative were Denmark, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. The initiative creates a venue that brings together naval and industry leadership to address naval shipbuilding limitations by innovation in areas like modularity, interoperability, and a less rigid and country-specific system of certification and standards. Advancing the state of naval ship propulsion is also within the scope of the initiative. Although France and the UK were not included in these discussions, similar measures to better connect naval and industry perspectives are ongoing in those countries as well.

| Table 7: Mediterranean/Southern Europe (2022-42) | ||||

| Country | Surface | Submarines | Patrol | MCMV |

| Italy | ||||

| Programmes | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| New Hulls | 15 | 4 | 10 | 12 |

| Acquisition Cost | 9,384 | 2,4 | 3,241 | 2,2 |

| Spain | ||||

| Programmes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| New Hulls | 9 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Acquisition Cost | 6,5 | 1,36 | 180 | 0 |

| Turkey/Greece | ||||

| Programmes | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| New Hulls | 28 | 14 | 136 | 6 |

| Acquisition Cost | 12,33 | 7,1 | 2,308 | 720 |

| Note: Costs in USD M |

Mediterranean/Southern Europe

The major countries covered by this region continue to support a combination of government-owned and/or privately held shipbuilding infrastructure. Spain’s industrial strategy has focused on making the shipbuilding industry more self-reliant. Spanish naval platforms are locally built by Navantia at their four major shipbuilding and repair facilities located at Ferrol, Cadiz, San Fernando, and Cartagena. Italy also relies on a single company – Fincantieri – for most new naval ship construction. Turkey’s shipbuilding infrastructure is less concentrated, with several commercial yards as well as the navy’s shipyards – at Gölcük and Istanbul – involved in building various sized naval and coast guard vessels up to and including large combatants, amphibious vessels and auxiliary vessels.

Italy and Turkey, with forecasted new platform spending over the next two decades in the range of USD 20-23 Bn, are making future naval investments at levels comparable to Germany (USD 24 Bn) and France (USD 29 Bn). Both countries are also investing to maintain, or even grow, capability in multiple mission areas, with programmes under construction encompassing high-end surface combatants, large offshore patrol vessels, and advanced conventionally-powered submarines. Large multi-purpose amphibious ships provide operational flexibility, whilst projects for auxiliary support ships ensure the ability to project and sustain naval forces for extended periods. Spain, at USD 8 Bn in forecasted spending, and especially Greece (USD 4.8 Bn), continue to struggle to halt steady declines in their naval force structures. Moreover, both navies show large gaps in projected MCMV, amphibious and auxiliary ship acquisitions, suggesting they are prioritising keeping at least some surface combatant and submarine warfare capability in place under current spending constraints.

In sum, shipbuilding capacity is southern Europe continues to be sized for current demand. Overall, this has remained steady but limited over the past decade. The region has yet to see any marked increases in naval building driven by the conflict in Ukraine. Turkey’s naval expansion, while still ambitious, has been curbed of late by the country’s economic issues, although somewhat offset by recent successes in export markets that have helped buffer pressures on the domestic naval budget.

Conclusion

The picture of Europe’s naval shipbuilding appears to have changed little one year after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The NATO alliance has demonstrated robust abilities to coordinate policies and military aid deliveries, while reinforcing mechanisms for cooperation in response to the Ukraine conflict. The pending ascension of Sweden and Finland, both with highly professional naval forces, strengthens NATO maritime capability significantly. Moreover, the conflict has demonstrated the continuing relevance of maritime capabilities (offensive and defensive), ranging from sea-based anti-ship and land attack strike, mine warfare, air and missile defence and especially non-conventional and special operations. Yet the lessons being learned among Europe’s navies from the Ukraine conflict have not – so far – translated into reversing the decline in Europe’s naval shipbuilding spending. Europe’s current naval shipyard infrastructure is capable of meeting today’s market demand. Should the Ukraine conflict support keeping European new naval ship acquisition budgets at current levels, that in itself would be a positive outcome from the perspective of Europe’s naval shipbuilders, large and small.

Bob Nugent

![The role of logistics in the Bundeswehr: A foundation for the planning and conduct of operations [Bundeswehr]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Bundeswehr-1-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Integrated logistics support data: Operational availability and lessons learned Fig 1: General data structure for a complex system of systems. [Guy Langenaeken]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/General-Data-Structure-for-CSoS_Guy-Langenaeken-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![System life cycle management: The next step to ensuring performance : A presentation from the NATO LCM 2025 conference in Brussels. [MRV/Javier Bernal Revert]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/1-NATO-LCM-2025_MRVJavier-Bernal-Revert-218x150.jpg)