The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has a clear roadmap to revitalise its Suppression of Enemy Air Defence capabilities.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO’s) Suppression of Enemy Air Defence (SEAD) and Destruction of Enemy Air Defence (DEAD) posture arguably took a back seat during alliance Counter-Insurgency (COIN) operations in Afghanistan. NATO SEAD/DEAD came to the fore once again during the alliance’s Operation Unified Protector (OUP) in 2011. OUP was waged to protect Libyan civilians against forces loyal to the country’s erstwhile dictator Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. The operation Unified Protector was performed on the high seas in and around Libya’s Mediterranean coastline. Meanwhile, NATO special forces were deployed on the ground. However, much of the effort was taken up by NATO air forces which mounted a seven-month air campaign.

Unlike Afghanistan, Libya boasted relatively capable albeit dated radar-equipped Ground-Based Air Defences (GBAD). According to the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), a London-based thinktank, these included medium-range, medium-altitude Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) systems like the S-125 Neva/Pechora (NATO reporting name SA-3 Goa) and the medium-long range S-75 Dvina (SA-2 Guideline). Complementing these was the S-200 (SA-5 Gammon) high-altitude, long-range system. Lower altitudes were protected by SHORAD (Short-Range Air Defence) assets including the French-supplied Rockwell International/Thomson Crotale SAM system. Soviet-supplied SHORAD systems included the 9K33 Osa (SA-8 Gecko) and PK35 Strela-10 (SA-13 Gopher). SAM batteries had organic radar providing initial target detection and tracking, and missile fire control. Alternatively, batteries would use data provided by radars elsewhere. Libya’s GBAD and the Libyan Air Force fighter fleet were networked into an Integrated Air Defence System (IADS) protecting the country’s airspace and air approaches. Nonetheless, it had vulnerabilities and was approaching obsolescence by 2011. As the air defence expert Dr. Carlo Kopp observed, “Libya operated one of the few remaining unadulterated 1980s Soviet air defence systems worldwide” at the time of OUP.

Credit: USAF

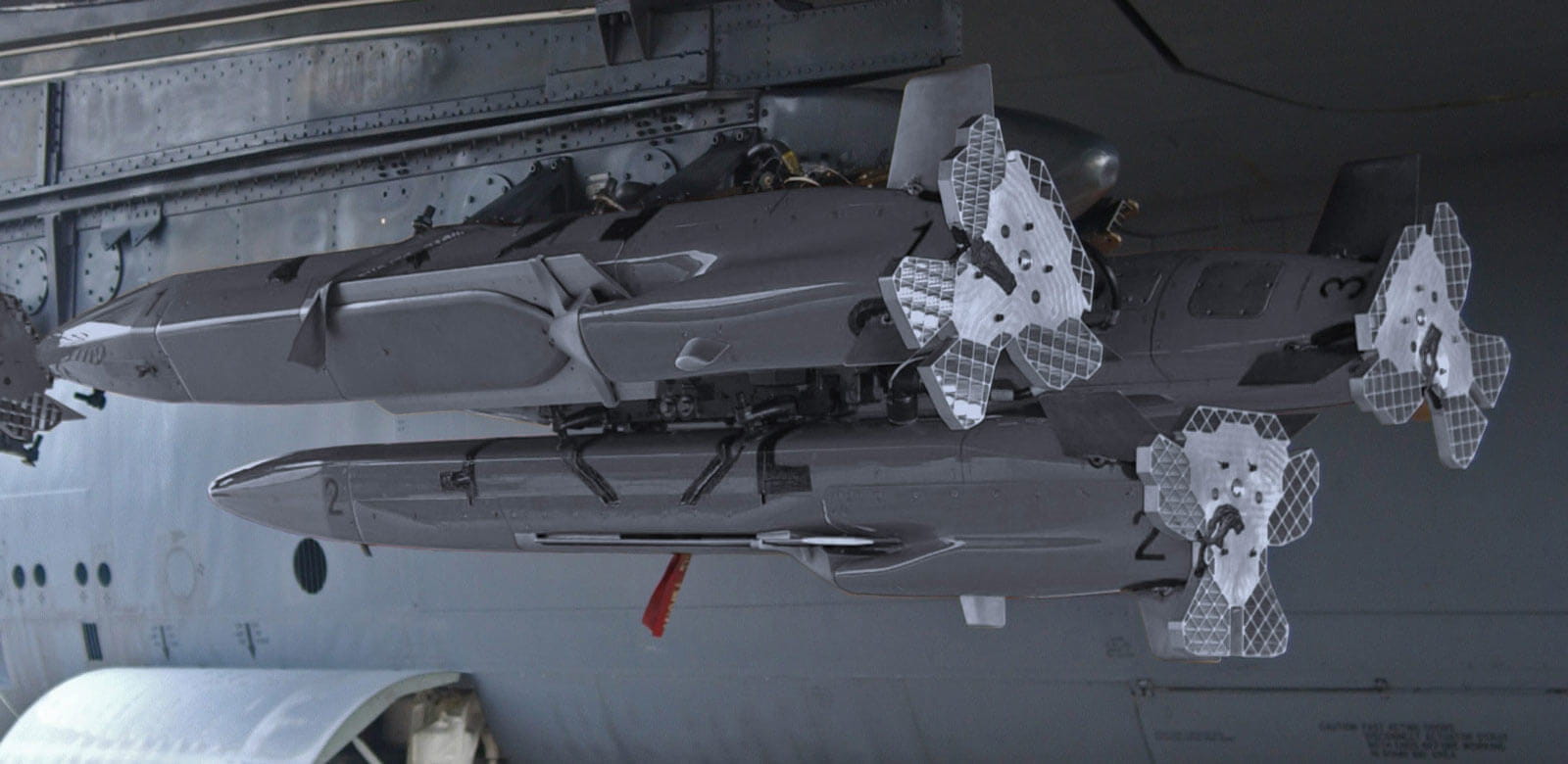

The antiquated nature of Libya’s IADS was rightly not taken on trust by NATO and the alliance deployed a formidable array of SEAD assets to protect its aircraft. The Aeronautica Militare (Italian Air Force) dispatched four of its Panavia Tornado-ECR dedicated SEAD jets. These aircraft deployed Texas Instruments/Raytheon AGM-88B/C High Speed Anti-Radiation Missiles (HARMs). HARMs were also deployed by US Navy Boeing E/A-18G Growler electronic warfare jets supporting the operation. While not dedicated SEAD assets per se, Royal Air Force (RAF) Panavia Tornado GR4A combat aircraft deployed the last RAF stocks of British Aerospace/MBDA ALARMs (Air-Launched Anti-Radiation Missiles) against Libyan radars. ALARM was finally retired from British use in 2013.

Electronic attack was provided by US Air Force (USAF) Lockheed Martin EC-130H Compass Call jamming aircraft. Compass Call attacked the radio communications networking the Libyan IADS and the Libyan armed forces in general. Additional electronic attack and HARM support against Libyan radars was provided by US Marine Corps’ Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowler jets.

The need to detect and locate Libyan ground-based air defence and Fire Control/Ground Controlled Interception (FC/GCI) radars necessitated a significant Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) collection effort. This effort collected data on Libyan radars and the radio communications networking the IADS and Libyan military. Italian Air Force Aeritalia/Alenia Aeronautica G222VS SIGINT aircraft supported this. They were joined by US Navy Lockheed Martin EP-3E Aries, USAF Boeing RC-135V/W Rivet Joint, Armée de l’Air (French Air Force) TransportAllianz C-160G Gabriel and Svenska flygvapnet (Royal Swedish Air Force) Gulfstream S-102B SIGINT platforms. NATO’s SEAD/DEAD effort paid off. The alliance experienced a single aircraft loss during the operation, comprising a US Navy Northrop Grumman MQ-8B Fire Scout Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) shot down by Gaddaffi loyalist forces on 21 June 2011.

Several NATO nations subsequently found themselves involved in Syria’s civil war which erupted three days before the alliance’s involvement in Libya began. The Syrian Air Defence Force (SADF) possessed a similar vintage of Soviet GBAD to Libya which formed the bulk of its IADS. Since 2014 the US has led a coalition of partners against the Islamic State (IS) insurgent organisation founded in 1999. IS’ operations in Syria and Iraq came to global attention as the movement gained control of parts of northwest Iraq. Operation Inherent Resolve was mounted by the US to drive IS out of areas it controlled and to curtail the group’s activities in Syria. Although Inherent Resolve can arguably be seen through the lens of post-9/11 counter-insurgency operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, it contained one important difference.

Putin’s Temper Tantrum

In September 2015, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin deployed his country’s forces to Syria ostensibly to help his ally President Bashir al-Assad against the forces seeking to depose him. Moscow was also no doubt mindful of the Russian Navy’s access to Tartus naval base on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. Tartus is Russia’s only permanent naval facility on this stretch of water. While the war in Libya featured antiquated air defences, and those of Syria were not much better, Russia’s deployment to the troubled country changed this dynamic. Her armed forces brought with them some of the country’s most advanced ground-based air defence systems. These threats included the S-400 (SA-21 Growler) high-altitude, long-range SAM system and Pantsir-S (SA-20 Greyhound) SHORAD platform.

Credit: Russian MoD

Ostensibly, these were not aimed at US and allied aircraft. After all, the US, her allies and Russia shared some of the same foes in Syria, notably IS. Nonetheless, the deployment occurred against a backdrop of worsening NATO–Russian relations. Mr. Putin’s distrust of the alliance had continued to grow since 2007. That year, he gave a hawkish speech to the Munich Security Conference held in the southern German city: “I think it is obvious that NATO expansion does not have any relation with the modernisation of the alliance itself or with ensuring security in Europe. On the contrary, it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust … We have the right to ask: against whom is this expansion intended?” A host of former Warsaw Pact countries, and three former Soviet republics namely Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, joined NATO in 2009. Mr. Putin believes NATO expansion into what he perceives as Russia’s sphere of influence is a danger to his regime. He felt a similar way about perceived Western support for so-called ‘colour coded’ revolutions in Georgia (2003) and Ukraine (2004) which he deemed contrary to Russia’s interests. This paranoia crystalised in Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. This action saw Russia’s occupation of Ukraine’s southern Crimea region and parts of her south-eastern Donbass area. In February 2022, Russia’s strategic muscles flexed once more, albeit in what seems to have been a major geopolitical blunder, with her second invasion of Ukraine. As of May 2023, Mr. Putin’s attempts to occupy the country and depose the government in Kyiv have been unsuccessful.

How do these geopolitical machinations affect NATO’s SEAD posture? The enmity existing between the alliance and Moscow has consequences. At the tactical, operational and strategic levels it means sophisticated air defences like the S-400 and Pantsir-S could be used against NATO aircraft should the alliance and Russia come to blows. This existential threat means that NATO must double down on its SEAD capabilities and posture.

The good news is that work is forging ahead in this regard. Delegates at the 2023 Association of Old Crows’ Electronic Warfare Europe conference and exhibition held in the western German city of Bonn from 15-17 May were updated on NATO’s efforts thus far. Momentum gathered following NATO’s summit in September 2014 held in Newport, South Wales. The event yielded a Defence Planning Package which committed the alliance “to further enhancing our capabilities,” according to the declaration issued by the heads of government attending. The purpose of the package was to inform the direction of national defence investments by members and “improve the capabilities that allies have in national inventories.” Chiefly NATO airpower needed to be capable of meeting and surpassing a near-peer threat. Air operations was one of the package’s work strands, specifically NATO’s joint airpower capabilities. Two areas requiring attention were flagged as AEA and SEAD, both of which are in the midst of being overhauled.

Credit: Thomas Withington

NATO’s SEAD capacity has arguably been left to atrophy since the Cold War. The decline of superpower rivalry and lack of major GBAD threat during NATO’s COIN operations being two contributing factors. NATO did face contested airspace during operations in the Balkans in the 1990s and in Libya last decade. These GBAD threats were prosecuted using similar SEAD capabilities to those fielded by the US and her allies during Operation Desert Storm in 1991 when Iraq was evicted from Kuwait. A decade of Russian military modernisation launched after the 2008 Russo-Georgian war shows that today’s GBAD threats faced by NATO are more sophisticated.

Visions for the Medium-Term

The first step in revitalising NATO SEAD involved drafting a vision paper establishing current alliance SEAD baselines and shortfalls. In a nutshell, this paper asked: what SEAD capabilities will be needed by 2030? Efforts to revitalise NATO’s SEAD posture are being led by its Aerospace Capability Group, Sub-Group 2. Collectively known as ACG3/SG2 this supports “the development of a joint NATO SEAD, and associated Airborne Electronic Attack (AEA) capability,” according to the alliance. ACG3/SG2 is focusing on SEAD capabilities that can be delivered from circa 2030.

A capability audit follows the vision paper. This looks at the SEAD capabilities NATO currently possesses and where capability shortfalls exist. Capabilities in NATO’s possession include stand-off and escort jamming support in the form of the E/A-18G. As well as deploying the AGM-88 HARM, this aircraft is receiving the Next Generation Jammer (NGJ) ensemble. The NGJ detects and electronically (and possibly cybernetically) attacks hostile radars and radio communications on frequencies of 500 megahertz to at least 18 GHz. Communications jamming capabilities include the EC-130H and the USAF’s new Gulfstream EC-37B Compass Call platforms which will assume this mission in the future.

Some SEAD shortfalls could be answered by technologies like support jamming to provide tactical and/or operational level electronic attack against hostile radars. Deception decoys are considered another ‘must have’ item. These can be used to deceive radars by transmitting false radar signatures. Current capabilities include Raytheon’s ADM-160C Miniature Air-Launched Decoy (MALD) used by the USAF. The earlier Raytheon ADM-160B version is believed to have been deployed in Ukraine by that country’s military. MALD could be joined by systems like MBDA’s Selected Precision Effects at Range – Electronic Warfare (SPEAR-EW). SPEAR-EW is an air-launched decoy under development and expected to enter service with the RAF in the coming five years.

Credit: Raytheon

The alliance is also looking at what kinetic options could be germane to the SEAD fight. As noted above, NATO already has dedicated SEAD weapons at its disposal like the legacy AGM-88B/C HARM missile. This weapon is being replaced by the extensively modified Northrop Grumman/Raytheon AGM-88E/F. We may see additional anti-radiation weapons in the future. It is noteworthy that some years ago MBDA proposed an anti-radiation variant of its Meteor radar-guided air-to-air missile.

Nonetheless, these efforts do not rest solely on materiel. The alliance will update its doctrine to reflect the findings of the vision papers and capability audit. NATO’s SEAD doctrine is enshrined in its Allied Joint Doctrine for Air and Space Operations. Future editions will not only fold in lessons learned for the alliance from Ukraine, but also reflect technological evolutions in the SEAD mission. A guiding principle of the doctrine will focus on the SEAD mantra of diversity and synchronisation of effects (kinetic, electronic and cyber), survivable delivery systems, connectivity, and coordinated information capture and distribution.

From an effects perspective, it is imperative that kinetic, electronic and cyber weapons can degrade, disrupt, deceive, destroy and/or deny red force GBAD capabilities at all levels of war. SEAD is not only about hitting the hostile radars – it needs to be seen holistically. Today’s IADS depend on sophisticated communications for command and control. They use a host of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets from satellites collecting transponder information from aircraft to global navigation satellite systems providing position, navigation and timing information. All IADS elements must be held at risk if SEAD efforts are to succeed. This requires capabilities beyond dedicated aircraft and weapons. For example, cyber effects could implant malicious code into the battle management systems an IADS depends upon. The USAF is already believed to possess such tools in the form of BAE Systems’ ‘Suter’ computer programme.

NATO’s Industrial Advisory Group (NIAG) will play a key role in helping address these capability gaps and the technologies and materiel relevant to supporting the SEAD mission. One of the NAIG’s study groups will provide a list of relevant capabilities that should be available to allies between now and 2030.

Use LUWES

As previous operations underscore, the US has provided the bulk of dedicated SEAD capabilities in previous operations. This dependence may diminish in the future. The Luftwaffe (German Air Force) is embarking on its ambitious LUWES (Luftgestützte Wirkung im Elektromagnetischen Spektrum; ENG: Airborne Effects in the Electromagnetic Spectrum) initiative. LUWES is procuring an array of new capabilities for the force. These include Eurofighter Typhoon-EW electronic warfare and SEAD/DEAD jets. Using kinetic, electronic and possibly cyber effects, these will perform the escort jamming role for strike packages of aircraft in contested airspace. A new airborne stand-off jamming platform will provide electronic and cyber effects beyond these lethal ranges. Airborne decoys and UAVs will provide these effects in the so-called ‘no escape’ zone. These are the ranges at which SAM batteries are at their most dangerous. All these capabilities will be networked together to receive timely intelligence and share data at the speed of light.

Credit: Thomas Withington

Germany provides Europe’s dedicated SEAD support and LUWES represents an important shot-in-the-arm to this end. Strongly contested airspace is back on the agenda as a hallmark of contemporary warfare as exemplified by Russia’s actions in Ukraine. NATO is not only addressing this threat but is seeking to overtake it as shown by the alliance’s evolving SEAD posture giving Mr. Putin and his cronies something else to worry about.

Thomas Withington

![Dual-use offensive/defensive interceptors: Panacea or chimera? An SM-6 missile is launched from the USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during Flight Test Standard Missile-27 Event 2 (FTM-27 E2) on 29 August 2017. [MDA/Latonja Martin]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/SM-6-Launch_MDALatonja-Martin-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Ripples in the air, rupture in the ether Pictured: 1L269 Krasukha-2 jamming system. Since 2008, Russia has greatly expanded its EW capabilities, and since 2022 it has gained valuable direct experience contesting the EMS in Ukraine, where continuous innovation occurs over very short timescales. [RecoMonkey]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1L269-Krasukha-2_RecoMonkey-Kopie-218x150.jpg)