In a worsening missile threat environment, the need for comprehensive and technologically superior ballistic missile defence (BMD) is more important for western allies now, than at any other time in world history.

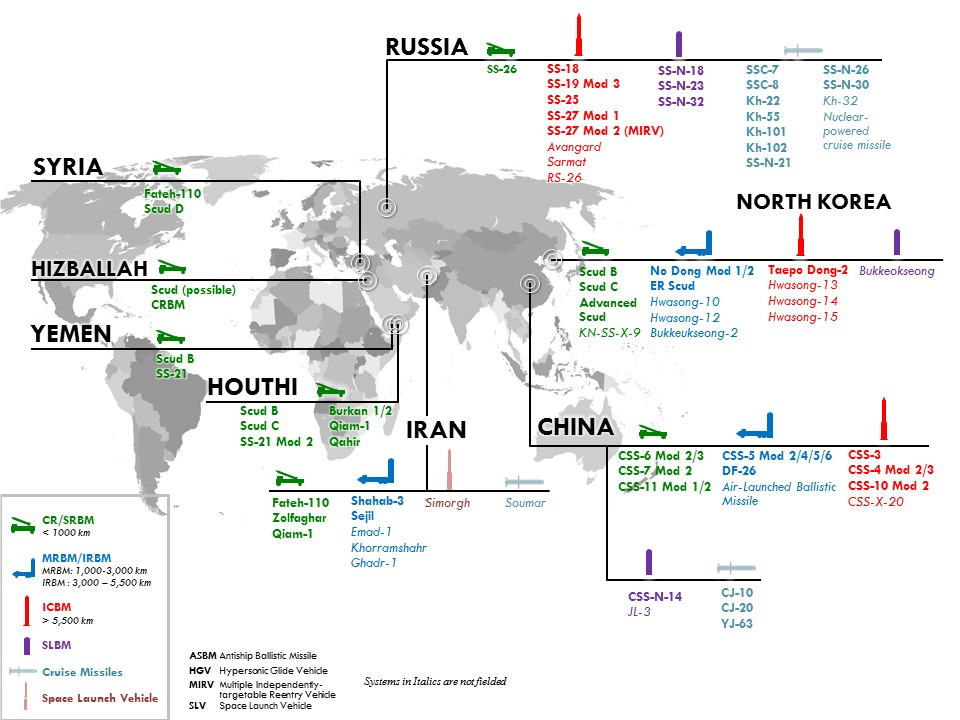

The US and its NATO allies have a great responsibility to protect their respective populations in what are, probably, the most dangerous geopolitical era of our lives. Missiles abound and are a means to project power both regionally and strategically. With burgeoning ballistic missile inventories, many state actors now have the ability to reach out across any distance, short or long, to target almost any nation they deem the enemy, with conventional, as well as nuclear weapons. Not only are ballistic missiles increasing in number, but also in range, sophistication and complexity by incorporating such tech as countermeasures to BMD systems. As a result, they’ve become more survivable, reliable and accurate, thereby threatening to reducing military options for allied commanders in the field, and potentially decreasing the survivability of their regional military land and sea assets.

Credit: US DoD MDR

It’s imperative, therefore, to defend against these clear and present dangers, and that requires collective strategy, forward planning, co-operation, interoperability, great resolve and, most importantly, technologically superior, multi-layered/tiered ballistic missile defences using the very latest technological advances to ensure success in their defensive aims against some of the most advanced weapons of their kind ever pointed in our collective directions. This article takes a look at the current alliance BMD framework and thinking, and then at latest upper-tier developments.

NATO’s Current and Evolving BMD

For NATO, the proliferation of ballistic missiles is an increasing threat to member populations, territories and forces, particularly with the proximity of several countries to alliance states that either have ballistic missiles or are attempting to develop and/or acquire them. As such, one of the alliance’s permanent missions is that of NATO Ballistic Missile Defence (NATO BMD), which forms a wholly defensive, deterrent component of the alliance’s Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) framework. As part of a strategic mix of conventional, space, cyber and nuclear forces, BMD plays a key role in protecting the alliance’s European populations, territories and forces as ballistic missile threats increase, particularly along the alliance’s southeast borders.

More than a decade ago, an expanded BMD capability was agreed as a core element of NATO’s defensive and deterrent raison d’être, and just over six years ago the Initial Operational Capability of NATO BMD was reached. Ongoing commitments by leaders of NATO member states were made at the 2022 Madrid Summit to continue implementing NATO BMD fully, requiring commonly funded assets, as well as voluntary contributions provided by several allies. The US European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA), for example, covers the US contribution designed to protect Europe against short, medium, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles launched from Iran, though without compromising protection from Russian threats. Indeed, prior to the invasion of Ukraine, NATO BMD was purportedly intended to largely counter the increasing threat posed by ballistic missile proliferation on the south-eastern borders of the alliance. This was in response to increasing concerns about Iran’s increasing numbers of missile tests, as well as the range and precision of its ballistic missiles.

While those aims of NATO BMD remain, the changing level of threat means its framework needs to adapt accordingly. In general, the alliance sees effective BMD as able to complicate hostile planning by potential aggressors, as well as providing valuable decision-making time for both military and civil command in response to imminent/ongoing missile attacks; BMD even contributes as a partial deterrent to nuclear missile threats, complementing, though not replacing, allied nuclear capabilities, in that regard.

Credit: IAI/MDA

Interestingly, alliance posture on BMD prior to 24 February 2022, stated that: “NATO BMD is intended to defend against potential threats emanating from outside the Euro-Atlantic area” and that: “NATO BMD is not directed against Russia and will not undermine Russia’s strategic deterrence.” This posture is, of course, now urgently being reviewed as of the Madrid event; it’s worth noting that at the Madrid Summit, allied leaders adopted the NATO 2022 Strategic Concept policy document that guides all alliance activities, including BMD, and which encompasses and considers the rapidly evolving strategic environment, which notes: “…authoritarian actors challenge our interests, values and democratic way of life.

They are investing in sophisticated conventional, nuclear and missile capabilities, with little transparency or regard for international norms and commitments”. In response to these authoritarian challenges the concept document states that: “NATO’s deterrence and defence posture is based on an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities, complemented by space and cyber capabilities. It is defensive, proportionate and fully in line with our international commitments”.

EPAA Moves

As for the EPAA, mentioned above, implementing this is core to the alliance’s IAMD and follows four-phased deployments, including that in which the US will provide upper-tier ballistic missile defence of Europe. Two of the four phases of EPAA are operational today, with an increasing number of allies already having provided assets, or having set development or acquisitions in motion for additional BMD assets, including upgraded ships with BMD-capable radars, ground-based air and missile defence systems, or advanced detection capabilities.

Ukraine notwithstanding, NATO BMD is based on voluntary national contributions, including nationally funded interceptors and sensors and hosting arrangements. It is also based on the command and control systems backbone delivered through the NATO BMD programme, which is commonly funded by all allies. In a nutshell at this time, Germany hosts the NATO BMD command centre at Ramstein Air Base, the US contributes through its EPAA, Turkey hosts a US BMD radar at Kürecik, Romania hosts a US Aegis Ashore site at Deveselu Air Base and Poland also now hosts an Aegis Ashore site, the construction of which was completed in October 2022 at the Redzikowo Military Base, with the US Missile Defense Agency (MDA) expected to confirm the site safe and technically capable later in 2023, at which point it will be taken under US Navy control before some operational control is expected to be transferred to alliance partners. In addition, Spain hosts four multi-mission, BMD-capable Aegis vessels at its naval base in Rota, as part of the EPAA and for use as part of NATO BMD, if required. Aegis is a capable system when it comes to BMD – in late 2020, the US Navy demonstrated the successful interception of an ICBM in mid-course flight, using an SM-3 Block IIA missile launched from the USS John Finn.

The above is by no means an exhaustive list, as several allies also offer additional integrated air and missile defence systems, such as PATRIOT or SAMP/T, or suitably capable naval ships, while others are developing and/or acquiring assets, which may, eventually, be suited for integration with NATO BMD.

Credit: US DoD MDR

Ukraine and BMD Rethink

As the IAMD framework was put together without a crystal ball to hand, it was aimed, as stated above, at countering ballistic missile threats emanating from outside the Euro-Atlantic area and not designed to defend against massive strategic retaliation from Russia. Therefore, as a direct result of the invasion of Ukraine, the core US EPAA document is under scrutiny to include BMD capabilities against such a Russian threat. It’s clear to see why; looking back to the start of the war waged against Ukraine, in the first month alone, around 1,000 ballistic and cruise missiles were launched from Russia, Belarus, and the Black Sea at critical infrastructure and civilian targets inside the country. Of those missiles, the 3M14 Kalibr, the 9M728 Iskander-K cruise missiles, and other Iskander-M and Tochka short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) were fired from Russian land and air-based platforms, with the Ukrainians having some limited air defence capabilities to stop them at that time. On its borders, US and NATO Allied PATRIOT missile batteries were then deployed/re-deployed into NATO member countries, US PATRIOTs to Poland and German and Dutch PATRIOTs to Slovakia. While massive missile strikes on Ukraine have, of course, continued throughout the war and been well documented, at time of writing, the dynamics have totally changed from those early days and the Ukrainians now have effective air defence assets in the form of approximately two PATRIOT batteries (both estimated to be under-strength), given the green light by the US in October 2022, and seemingly even proving effective against Russia’s Kh-47M2 Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missiles. Furthermore, according to Ukrainian defence intelligence sources, Russian theatre ballistic missile stocks are running critically low.

BMD as Part of IAMD

To round off this brief look at current NATO BMD thinking, this crucial missile defence capability is a key component of the alliance’s overall IAMD framework to protect against air or missile threat or attack. This is a vital element of NATO’s deterrence, defence and ability to provide a strategic response to any event, so the alliance maintains a desired level of control in the skies, so as full a range of alliance missions can be carried out on the ground and at sea. IAMD is designed to provide 360° cover enabling it to detect, identify and engage any threat from any direction. While in peacetime, NATO BMD remains one of the two major ongoing IAMD activities alongside air policing, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO IAMD is adapting to address all air and missile threats, including Russia’s hypersonic weapon and drone threats. Measures taken by the allies to enhance NATO IAMD in response to the invasion of Ukraine, for instance through the movement of the Patriot batteries mentioned earlier, are a demonstration of how allied cooperation under IAMD works.

Credit: Lockheed Martin

It is also worth noting that in May 2023, it’s worth noting that a PAC-3 MSE interceptor was successfully test launched from a German-modified M903 Patriot launcher at White Sands, under simulated tactical/operational test conditions conducted by the German Air Force against a virtual tactical ballistic missile target to prove compatibility between PAC-3 MSE and the German-modified Patriot M903 launching station. MBDA Deutschland partnered with Lockheed Martin to perform the necessary modifications of the launcher to enable the integration of the PAC-3 MSE missile, with the test being a critical final step before delivery of the first PAC-3 MSE shipment to Germany and follows the 2019 agreement between US and German Governments for German PAC-3 MSE procurement.

Upper-Tier Interception Developments

Moving away from alliance thinking to some recent BMD system developments, (though just a couple of the many that could be discussed), let’s now look at some recent upper-tier/mid-course interception developments with the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) from Lockheed Martin and the joint US/Israeli IAI Arrow 3.

Scene setting: mid-course is the phase of flight between the boost phase after a ballistic missile is launched and the terminal phase of its flight, once it has re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. The mid-course phase in space can last from a few/several minutes for shorter and medium-range missiles, to as long as 20 minutes for an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which offers the longest potential timeframe in which a defensive system can be used against an incoming missile, giving the defender time for both decision-making and an interception. This also means that an anti-ballistic missile (ABM) rising to meet the threat has a large exo-atmospheric area in which to conduct its interception. That said, these factors, in turn, require such an ABM to be large and supported by powerful ground-based radar systems, space-based sensors, and capable of evading space-based decoys.

THAAD Moves

Built to defend against short, medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles, THAAD is the only US system designed to intercept targets at upper-endoatmospheric to lower-exoatmospheric altitudes. The system uses a hit-to-kill defeat mechanism to destroy threats with kinetic energy from a direct impact, which is also intended to neutralise lethal payloads before they reach the ground. THAAD continues incremental capability improvements within the weapon system to continually improve performance against current and emerging threats. The first THAAD battery was activated in May 2008 and the seventh in December 2016.

Credit: Lockheed Martin

According to the manufacturer, THAAD’s continued incremental capability improvements within the weapon system have led to its integration with the Patriot Advanced Capability (PAC)-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE), demonstrated in March 2022 when the US Missile Defence Agency (MDA) in partnership with the US Army Programme Executive Office Missiles and Space, US Army Space and Missile Defence Command, and Ballistic Missile Defence System Operational Test Agency (BMDS OTA), tested the integration of THAAD with the Patriot missile defence system. The test, designated Flight Test THAAD Weapon System (FTT)-21, was conducted at the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico and achieved its objective, with the THAAD weapon system launching two PAC-3 MSE interceptors, which successfully took out a Black Dagger target. MDA Director Vice Admiral Jon Hill said that the test marked a milestone for the integration of the two weapon systems, enabling commanders on the ground the ability to “use the right missile for the right threat at the right time”.

FTT-21 was the first live intercept flight test of software upgrades that now provide THAAD with the capability to compute PAC-3 MSE firing solutions, communicate with an M903 Patriot Launching Station, and simultaneously control multiple PAC-3 MSE interceptors in flight. The integration of the PAC-3 MSE interceptor into THAAD allows it to be launched earlier, enabling a longer fly-out time, which, in turn, potentially increasing the defended area, and offers an integrated layered defence. A month after the FTT-21, the MDA awarded Lockheed Martin a USD74-million contract to produce an eighth THAAD battery for delivery to the US Army in 2025. VP of Upper Tier Integrated Air and Missile Defence at Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control, Don Nimblett, said at the time that continued confidence in the THAAD system and its “unique endo- and exo-atmospheric defence capability” were behind the award, adding that, “With 16 of 16 successful flight test intercepts and recent combat success clearly documenting the effectiveness of THAAD, adding an eighth battery will further enhance readiness against existing and evolving ballistic missile threats.”

Credit: Lockheed Martin

In October 2022, the company delivered the 700th THAAD interceptor to the MDA as part of a USD 1.4 Bn award in March 2022 for additional interceptors, for both the US Army and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This milestone was met just 14 months after Lockheed Martin delivered the 600th THAAD interceptor to the US in August of 2021. Despite March 2022, contract, the MDA also exercised a USD 304.9 M option for further interceptors in April 2022.

AWS and Arrow 3

Another upper tier/mid-course BMD system gaining traction at the moment is the Arrow 3 interceptor, which is part of the Arrow Weapon System (AWS), jointly developed by Israel Missile Defence Organisation (IMDO) and the MDA. It forms a central part of Israel’s multi-layered defence array based on four layers: Iron Dome, PATRIOT, David’s Sling, and the Arrow-2 and Arrow-3 systems. Whereas the Arrow 2 interceptors are designed for endo and exo-atmospheric interception capabilities, the Arrow 3 interceptors are upper tier, mid-course, exo-atmospheric interceptors for longer-range threat engagement. The missiles are two-stage, solid propellant designs, comprising booster and sustainer sections as well as a hit-to-kill defeat kinetic kill vehicle. The Arrow system (also known as the Arrow Weapon System; AWS) provides radar detection, tracking, intercept data to both Arrow 2 and 3 interceptors on any incoming TBMs over a large footprint, thereby protecting strategic assets and population centres with a multi-layered system. For its part, Arrow 3 is designed to intercept and destroy the latest, longer-range threats, especially those, including ICBMs, carrying weapons of mass destruction; a fire-control system guides the interceptor to its target, but Arrow 3’s kill vehicle is equipped with advanced, high-resolution optoelectronic sensors imparting long-range acquisition capabilities, enabling it to home in precisely on its prey over a very large defended area. Even though its overall manoeuvre envelope is large, its time-of-flight is short, thereby enabling a large number of interception opportunities within the mid-course environ. By integrating into the overall Arrow system and complementing current and future blocks of Arrow 2 interceptors, Arrow 3 completes the upper-tier engagement capability of this now multi-tier BMD system.

Credit: IAI/MDA

In January 2022, the IMDO of the Directorate of the Defence Research and Development (DDR&D) at Israel’s Ministry of Defence, together with the US MDA and participating Israeli Defence Forces, conducted a successful flight test of the AWS and the Arrow 3 interceptor at a test site in central Israel. AWS radars detected the target and transferred data to the battle management control (BMC) system, which analysed the information and established a defence plan, resulting in the launch of two Arrow 3 interceptors toward the target for a successful mission completion. Once again commenting for the MDA, Vice Admiral Jon Hill said that the test had been designed to challenge every element of the AWS and that data from the whole event would help guide future system development, adding, “MDA remains committed to assisting the Government of Israel in upgrading its missile defence capability against current and emerging threats.”

IMDO director, Mr Moshe Patel, said at the time that since a successful series of tests in Alaska in 2019, the Arrow system’s capabilities had been significantly extended and that this latest successful test had been a ‘complicated flight’ involving the complete AWS and the Arrow 3 interceptor and would help the Israeli Ministry of Defence to continue in its efforts to enhance and upgrade Israeli multi-tier missile defence capabilities to meet any and all emerging threats in the region. The IMDO, MDA and the US Government have collaborated on Israel’s current missile defence developments for more than 30 years.

For some months now, Germany has been in discussions with Israel about acquiring Arrow 3 to strengthen its air defence capabilities, effectively creating a new multi-layered, BMD shield that would also include and be integrated with the German IRIS-T and the US Patriot system. Towards the end of April, it was reported that these talks had reached an advanced stage. This major development is part of Germany’s new approach to defence and military spending, as a direct result of the war in Ukraine. The purchase was reported to have been approved in principle by US President Biden in March 2023.

Tim Guest