The US Army remains confident that it will become the first Western military service to operationally field a hypersonic weapon, potentially as early as autumn of 2023.

Through a joint service memorandum, the US Navy and the US Army are collaborating on the development of a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV). This category of weapon is launched atop a carrier rocket and transported to exoatmospheric altitude, during which it attains hypersonic speed, and then separates from the booster, transitioning to an unpowered glide mode for the remainder of its flight. In contrast to ballistic missiles, HGVs manoeuvre during their unpowered flight phase, enabling them to evade missile defence systems and denying the enemy certainty regarding the ultimate target.

Credit: Lockheed Martin

The core system being developed by the Navy and Army will be adapted to meet the services’ respective operational requirements and concepts. Lockheed Martin is acting as prime contractor and systems integrator for the Army variant, which is designated the Dark Eagle Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW). The official development agency is the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO).

Dark Eagle Profile

Despite the “long-range” designation, LRHW is a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM). According to Douglas Bush, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for acquisition, logistics and technology, the weapon system’s range is circa 2,700 km; during a portion of its flight it is expected to attain top speeds of around 6,000 km/h or Mach 5, Bush confirmed in August 2023. However, the glide vehicle’s maximum speed during the high altitude portion of its flight is expected to be significantly higher than this.

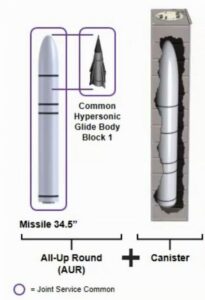

The core component is the Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB) which was developed by the Navy and is produced by Leidos subsidiary Dynetics Incorporated. In addition to the kinetic-energy warhead, the C-HGB integrates the guidance system, cabling, and thermal shielding. The glide body is carried in a nose cone mounted atop a two-stage solid-fuel rocket booster which is produced by Lockheed Martin. The assembled system is referred to as the vertical launch All-Up-Round (AUR).

An LRHW battery consists of four tractor-trailer-mounted launchers utilising modified M870A4 trailers; each transporter-erector-launcher (TEL) carries two ready-to-launch AURs in launch canisters. A mobile battery operations centre (command and control), crane-equipped logistics vehicles for reloading launchers, and additional support vehicles complete the unit. The Army plans to utilise the existing Advanced Field Artillery Tactical Data System (AFATDS) for command and control. The system can be airlifted by C-17 aircraft. The 24 m long tractor-trailer launch vehicle has limited off-road manoeuvrability. It is primarily intended to be road mobile, switching locations frequently to threaten enemy assets from varying directions while evading counterfires.

The LRHW remains one of the US Army’s main acquisition priorities. According to a 2022 Army budget document, the programme will “provide the Army with a prototype strategic attack weapon system to defeat A2/AD [anti-access/area denial] capabilities, suppress adversary long range fires, and engage other high payoff/time sensitive targets.” The ability to quickly target mobile command centres, mobile missiles, or other high-value targets with a system that is difficult to detect and intercept is considered a force multiplier, especially in a conflict against a peer- or near-peer adversary. Given the high value nature of potential targets and the limited number of available hypersonic missiles, the LRHW is being treated as a quasi-strategic asset. Operationally, US Strategic Command will identify targets and develop missions for the expeditionary batteries.

Testing Delays

The development programme goes back to a March 2019 directive by the Secretary of the Army to accelerate delivery of a “prototype ground-launched hypersonic weapon with residual combat capability” by Fiscal Year 2023 (which ends 31 September 2023). Given the head start of Russia and China in developing hypersonic weapons, the Pentagon prioritised LRHM and its Navy counterpart, pursuing both programmes using rapid prototyping authorities. Lockheed Martin was awarded the LRHW contract in August 2019.

The Navy and Army have conducted joint tests to evaluate components of the hypersonic weapon systems. The most notable of these was Flight Experiment 2 which took place in March 2020 at the Pacific Missile Range Facility in Hawaii. The C-HGB was launched atop a generic booster rocket (not representative of the AUR). After a short flight the glide body separated from the booster and set course for the designated ground target, which it precisely impacted. Significantly, the demonstration validated the glide body’s aerodynamics, stability, and control.

However, the 2021 annual report by the Pentagon’s Director of Operational Testing and Evaluation (DOT&E) found Flight Experiment 2 to have several limitations. “The flight test provided warhead performance data, but also lacked operationally representative targets. Neither programme has yet performed arena testing on the operationally representative warhead, which is fundamental to the development of the lethality model.” The report also faulted that no data was available to evaluate the Dark Eagle system’s survivability in a contested environment.

A total of three LRHW-specific flight tests – including two of the complete AUR – were planned for the 2022-2023 timeframe to progressively prepare for operational certification of the Dark Eagle. To date, not a single one of these has been successfully completed. The latest setback was announced on 6 September 2023. The scheduled validation flight test was cancelled for unspecified reasons following the pre-flight checks. This followed an earlier test cancellation in March 2023 after a battery failure was detected during the pre-launch procedure. As of September 2023 the flight testing programme is a full year behind schedule.

Fielding in Sight?

Leading up to the September 2023 aborted validation flight test, Army leaders had publicly displayed great confidence in the system’s progress. Speaking at the 8th Annual Army Summit organised by the Potomac Officers Club (a private organisation) on 7 August 2023, Assistant Secretary Bush expressed optimism that LRHM would be operational by autumn 2023. “The Army’s been in this business before – we used to have a lot of MRBMs. We’re coming back. Once we get through some – hopefully they go well – flight tests this summer, we will be actually fielding that system to a unit that could go to war this fall.” Bush specifically said that the (now cancelled) event was to be the “most important one” of two as it constituted an “end-to-end evaluation” of the system.

On 10 August 2023, the RCCTO’s director, Lt. General Robert Rasch confirmed the service’s optimism regarding the road to certification. “We’re birthing [LRHW] in RCCTO but for the long-term, for the second battery and the third battery, the sustainment, and the design improvements over time, those will happen” at the Program Executive Office (PEO) Missile and Space, Rasch said during a space and missile defence symposium at Huntsville, Alabama. However, Rasch did not commit to a specific timetable. “Once we [complete] end-to-end testing, and we have confidence in the design, there are missiles lined up in various stages of production ready to finish buttoning up and get those out to the field.”

First Operational Unit Standing By

The first operational unit to field the LRHW will be Bravo Battery of the 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment (5-3 FA) at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington state. The battalion is the strategic long-range fires unit of the 1st Multi-Domain Task Force (1st MDTF), which was formed in 2017 to test new technologies and operational concepts with a focus on defeating enemy A2/AD networks.

The battalion received the full LRHW panoply – minus the still developmental AURs – in 2021 in order to develop and practice operating procedures. The results of this New Equipment Training (NET) programme were tested in four three-week increments culminating with a field exercise in February 2022. According to the accompanying Army press release, “Bravo Battery’s primary objectives included air transportation drills, security procedures, canister reload operations, operational emplacement of equipment and performing fire missions […] enabling strategic objectives across echelons.”

In February 2023 the unit deployed the system from its home base over 5,000 km to Florida (as part of Exercise Thunderbolt Strike) in a full rehearsal of expeditionary hypersonic launch operations. According to the Army, the deployment exercised critical command and control linkages between the joint US Indo-Pacific Command and US Strategic Command, as well as the US Army Pacific command, the RCCTO, and the 1st MDTF. The validation of the recently developed and refined procedures should enable the unit to be operational with the hypersonic missiles soon after receiving the AURs, and will form a baseline concept of operations for future LRHW batteries.

(Credit: US Army)

At this point it must be noted that the Army has always intended for the planned 2023 operational capability to be a provisional capability which could be deployed in a contingency. Among other things this reflects the fact that the initial set of AURs which are to be provided to the 3-5 FA will still be classified as prototypes which are to serve as a baseline for the subsequent acquisition programme of record. In many ways the eventual outfitting of the first battalion with the provisionally certified weapon system will still constitute part of the Army’s learning curve. Under the extant timeline (which to date has not been officially adjusted) the second Dark Eagle battery is expected to be fielded in Germany in 2025. The weapon system’s Initial Operational Capability (IOC) is to be declared at that point.

Programme Going Forward

Despite budget cutting in some other sectors, the Army continues to prioritise long range fires. According to Army budget director Major General Mark Bennett, an additional USD 1 Bn are being specifically sought “to support the further development and demonstration of the prototype battery that will provide the Army a strategic attack weapon system to defeat anti-access, area denial capabilities,” which is the 3-5 FA’s Bravo Battery. Bennett made this statement on 13 March 2023 during a budget briefing for the press.

Despite the testing delays, the service remains determined to field LRHM as soon as operational certification can be achieved. Referencing the 6 September 2023 cancellation, Army Under Secretary Gabe Camarillo stressed that he remains “very confident in the programme.” Following the weapon system’s ultimate certification, the RCCTO will transfer LRHM to the PEO Missiles and Space, where it will transition from a developmental and evaluation project to an acquisition programme of record.

Up until now, this transition has been planned for the 4th Quarter of FY 2024. Army officials themselves have repeatedly termed this schedule as “aggressive” and conceded that the ambitious timeline carried inherent risks. Given the fact that the testing schedule is a year behind the original plan, and that no date for the next attempt at a test flight has been announced, it seems likely that the transition to a programme of record will have to be pushed up. The alternative would be to proceed to an operational capability with fewer or no full-fledged flight tests, consciously accepting the greater risk inherent in such an approach.

Regardless of when the system becomes operational, future technology upgrades have been pre-programmed into the procurement cycle, with each new battalion set expected to be incrementally improved over the previous missiles. One planned technology insertion would provide the ability to remotely reprogramme or update targeting data after launch, in order to enable engagement of moving or relocated targets.

To date a total of five batteries are planned, one for each of the Army’s Multi-Domain Task Forces. The headquarters and cadre elements of the 2nd and 3rd MDTFs have been established in Germany and on Hawaii, respectively, in line with the stated intent to dedicate two such formations to the Indo-Pacific region and one to Europe. The fourth and fifth MDTF are yet to stand up. The fourth could be oriented either to the Arctic or form a third Indo-Pacific MDTF (in June 2023 Japanese media reported that negotiations with Tokyo were in progress), while the fifth and final is expected to be oriented towards global deployments. The allocation of a LRHW battery to each of these formations will guarantee a limited but formidable expeditionary strike capability, with a special focus on conflicts with China or Russia.

Sidney E. Dean