The war in Ukraine has clearly shown the value of anti-ship missiles. Both Bulgaria and Greece are NATO member states that, due to significant threats and a risk of war, must strengthen their capabilities in this regard.

One of the lessons learned from the Russian full-scale aggression against Ukraine initiated in 2022 relates to the naval domain, including the threat that enemy warships can pose. Despite its limited potential, the Russian fleet effectively cut off Ukraine from the Black Sea, entirely closing its ports. Russian naval dominance in the Black Sea has also constrained the operational freedom of Ukrainians on land. In the initial year of the war, Ukrainians were frequently alarmed by a possibility of a Russian naval invasion. This threat compelled Ukraine to maintain credible forces in proximity to its coast, such as near Odessa.

In this regard, the war in Ukraine has highlighted a fundamental importance of anti-ship systems, especially coastal-based ones, which complement sea-based launchers excellently and sometimes, as in the case of Ukraine, have to replace them. As soon as Ukraine deployed its relatively modest anti-ship systems, warships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet became a vulnerable target. Russia suddenly lost its full operational freedom. In addition to sinking the “Moskva” 186-m guided missile cruiser with just two Ukrainian R-360 NEPTUNE anti-ship missiles, Ukraine also damaged a Russian shipyard in the Crimean port of Kerch and facilities in Sevastopol. Several ships, including a submarine, were reportedly damaged.

Bulgaria

One of the NATO member states that is still building its anti-ship capabilities and, at the same time, faces significant delays in this area is Bulgaria. Currently, its vulnerable coastal-based defense relies on the ex-Soviet 4K51 RUBEZH system with the P-15 TERMIT missiles (still in the inventory but with limited operational value). The only modern and highly advanced anti-ship system that is yet to be deployed is Saab’s long-range (200 km) RBS15 Mk3. It is expected to be integrated with two new 90-m multirole modular patrol vessels manufactured locally by MTG Dolphin JSC in cooperation with NVL Group (formerly known as Lürssen). They are to be delivered between 2025-2026. The Bulgarian Navy will be the eighth user of the RBS15 family, joining Sweden, Germany, Poland, Finland, Algeria, Thailand, and Croatia.

In the face of financial constraints and numerous needs, as is the case in Bulgaria, a legitimate question arose about priorities. A procurement of sixteen F-16 Block 70 aircraft undoubtedly places a modernization of an outdated radar network even higher among the priorities. However, at the same time Bulgaria needs to upgrade its anti-ship capabilities. Despite the above-mentioned procurements of new patrol vessels, Bulgaria will be able to deploy only a modest number of RBS15s. Certainly not enough to create a credible deterrence and to meet all threats. A purchase of additional systems, including coastal-based ones, is more a political than financial decision, as Bulgaria is expected to reach 2% of GDP on defense expenditure in 2024.

Although Bulgaria, seeking to acquire two used submarines to bolster its naval deterrence, is situated among friendly states, it does not imply an absence of challenges to contend with. A substantial threat emanates from the Black Sea, where the ports of Varna and Burgas are located. Not without reason, Prime Minister Nikolai Denkov recalled that in 1915 the Russian warships bombed Varna, causing human casualties. There are now apprehensions that Russian aggression may extend beyond Ukraine and that the Kremlin’s actions could heighten tensions in the upcoming years.

The most vulnerable NATO member states could fall prey to such actions. Alongside Romania, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, Bulgaria stands as a likely target for a Russian operation involving armed intimidation. Bulgarian Defence Minister Todor Tagarev was correct in concluding that military hostilities in the Black Sea cannot be ruled out. For a country like Bulgaria, which is still grappling with the modernization of its land forces, stopping a potential aggressor as far as possible from its own borders and shores holds vital significance. To enhance its capabilities, Denkov hinted in September 2023 that Bulgaria would acquire additional anti-ship missiles for its vessels. While Denkov’s announcement is logical and understandable, Bulgaria should take further steps to fortify its defense by considering dual use of the already chosen anti-ship capability, namely as coastal-based anti-ship battery. This notion has received endorsement from the Bulgarian Ministry of Defense on multiple occasions, but as of now, no specific details, including timelines, have been provided.

Greece

Despite having a larger defense budget than Bulgaria and possessing more modern and better-equipped armed forces, Greece, Bulgaria’s neighbor, faces a considerably more demanding situation. Their challenge arises from extremely sensitive relations with Turkey, which periodically escalate into armed confrontations. Tensions over sovereignty and rights to explore underwater resources have been steadily increasing in recent years. According to Greek data, in 2022 alone, Turkey committed over 2 thousand violations of Greek territorial waters. As a response, Greece does not hesitate to allocate significant spending to armaments, accounting for 2.3% of its GDP. The naval domain, including anti-ship capabilities, stands among the top priorities for the government in Athens.

From an operational standpoint, Greece’s security environment poses greater challenges, primarily because the Aegean Sea is more geographically diverse, with nearly 1.5 thousand islands and islets, making anti-ship operations more demanding. Additionally, Turkey maintains a qualitative advantage over Greece, thanks to its ambitious shipbuilding program. Athens, on the other hand, still contends with relatively weak deterrence and counter-strike capabilities, while its area of responsibility is wide ranging, extending to the Eastern Mediterranean between Crete and Cyprus.

At the same time, Turkey has been modernizing not just its fleet but also its missile capabilities. This includes the ATMACA all-weather anti-ship missiles designed for use by various Turkish warships and adaptable for deployment in a coastal-based configuration. In essence, the Hellenic Navy urgently requires an upgrade in its anti-ship capabilities to bolster deterrence and establish a much-needed balance of power. Consequently, this would diminish the risk of armed conflict, fostering greater stability and security in this fragile sub-region.

Greek anti-ship capabilities rely primarily on 13 frigates, all of which are aging. The Hydra-class (MEKO-200HN), launched in the early 1990s, and the nine ships of the Elli-class (ex-Dutch Kortenaer-class), launched in the 1970s and 1980s, make up this fleet. Both classes are equipped with HARPOON missiles, considered obsolete and scheduled for withdrawal in certain NATO countries, such as the United Kingdom and Spain. Only four new FDI frigates (Belharra-class) will be armed with MBDA’s MM40 EXOCET Block 3C missiles (the Hellenic Air Force is equipped with the AM39 EXOCETs). While these recently ordered ships from France will significantly enhance capabilities of the Hellenic Navy, it remains insufficient in light of Turkish modernization efforts, challenges in the maritime domain, and Greece’s vast area of naval responsibility.

Looking for a solution

While Bulgaria and Greece differ strategically, economically, and militarily, they share a common concern about potential threats. Both countries are actively preparing for a possibility of conflict with larger and stronger adversaries. They face relatively similar challenges, dealing with limited resources and an urgent need to modernize their fleets while significantly expanding anti-access capabilities in their maritime zones.

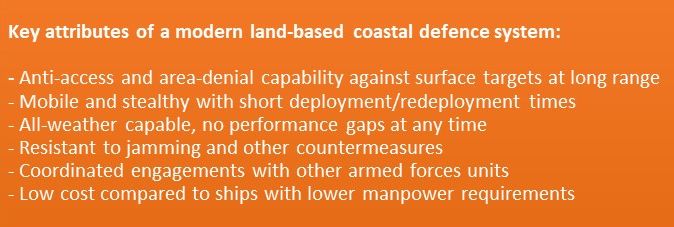

In both cases, investing in modular coastal-based battery systems equipped with long-range, and low sea-skimming, missiles capable of resisting enemy electronic warfare defenses and repelling even relatively large invading forces, appears to be a logical and strategic move. The modern defense market offers a diverse array of highly effective, versatile, NATO-compatible, and missiles with a long-term development roadmap that promises additional capabilities in the future.

This is particularly relevant to missiles designed for both ship and truck platforms. Such a solution not only significantly reduces logistical costs and minimizes maintenance issues, but also enhances coordination across various platforms. Moreover, a versatility of modern anti-ship missiles derives not just from their adaptability and ability to be deployed at sea or on land, but also from their effectiveness against a variety of targets. In other words, the future belongs to long-range anti-ship missiles that possess deep-strike attack capabilities, can be deployed on various platforms, and employed in diverse weather conditions, even without support from a third party (which means that although these missiles typically utilize GPS-transmitted data, they can also rely solely on inertial navigation if needed).

Coastal-based batteries unquestionably cannot replace ship-based launchers; however, that is not their intended role. Instead, they are designed to serve as a complement and reinforcement to naval assets. While warships undoubtedly offer greater operational flexibility, they are limited by the fact that they cannot be everywhere at once. They are also significantly more expensive and demand greater manpower compared to mobile land-based anti-ship systems. The manpower challenge has already been recognized by several NATO countries, and Bulgaria, as officially stated by Deputy Defence Minister Atanas Zapryanov in late October 2023, is among them.

These land-based systems can be dispersed and concealed over a relatively wide area. Their final configuration, including a number of launchers, radars, auxiliary sensors, and other sub-systems (such as various C2 and communication solutions), depends on customer’s requirements, including operational needs and financial resources. Through integration with external sensors like drones, radar stations (including mobile radars), and aircraft, anti-ship launchers can remain lethal without being easily detected. Furthermore, unlike ships, they can continue to operate in a highly hostile environment even without air superiority. The situation in Ukraine serves as a prime example – Ukraine is unable to utilize its fleet, but coastal-based missiles have remained operational, posing a constant threat to the Russians.

It’s not surprising that additional NATO member states are opting to acquire land-based anti-ship solutions, either by developing such capabilities from the ground up or by augmenting their existing arsenals. Among states currently procuring such solutions are Poland, Latvia, Norway, Germany, Romania, Spain, Estonia, the Netherlands, and Turkey. Outside of NATO, investments in this area are being made by countries such as Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

Would these systems strengthen Bulgaria and Greece, effectively enhancing their deterrence capabilities? Undoubtedly, Bulgaria lacks financial resources to establish a large and effective fleet of ships, especially considering additional investments required by other branches of its military. Similarly, Greece, while possessing superior naval and strike/anti-strike capabilities compared to Bulgaria, also faces economic challenges following its bankruptcy in 2010. Now, Greece must find financial resources to modernize its aging fleet. The prompt acquisition of modern land-based anti-ship systems will allow both nations to meet their operational needs, as driven by an escalating threat landscape, in a cost-effective way.

Dr Robert Czulda, Professor, University of Łodz, Poland

![Dual-use offensive/defensive interceptors: Panacea or chimera? An SM-6 missile is launched from the USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during Flight Test Standard Missile-27 Event 2 (FTM-27 E2) on 29 August 2017. [MDA/Latonja Martin]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/SM-6-Launch_MDALatonja-Martin-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Ukraine and the Western Balkans – from parallel pasts to a shared future Participants at the fourth Ukraine-Southeast Europe summit gathered in Odesa on 11 June 2025. [Office of the President of Ukraine]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Odesa-summit-2025_Office-of-the-President-of-Ukraine-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Ripples in the air, rupture in the ether Pictured: 1L269 Krasukha-2 jamming system. Since 2008, Russia has greatly expanded its EW capabilities, and since 2022 it has gained valuable direct experience contesting the EMS in Ukraine, where continuous innovation occurs over very short timescales. [RecoMonkey]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1L269-Krasukha-2_RecoMonkey-Kopie-218x150.jpg)