Uncrewed capabilities have often been touted as ‘game changers’, at strategic and operational levels. The current crises and conflict across the Middle East are demonstrating how one type of uncrewed system – uncrewed air vehicles (UAVs) – can have such impact.

Western militaries have for some time been working on delivering new capability and operational outputs through using uncrewed systems, and are slowly introducing them into operations on land, at sea, and in the air. However rogue states, and now non-state actors, are introducing the capability far more quickly, including in high-intensity operations. Here, the Middle East maritime environment takes centre stage.

In July 2021, off the coast of Oman, the tanker M/V Mercer Street was attacked with an uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV). Two crew were killed. According to materials published by US Central Command (CENTCOM) following the incident, the attack “required calculated and deliberate re-targeting” of the vessel, following a failed attack using two UAVs the previous day. After analysing the attack, damage to the ship, and component debris recovered, CENTCOM stated that the attacks were conducted by Iran.

In a conclusion that pointed to emerging capability and operational trends using UAVs – a conclusion that would prove to be correct – CENTCOM said “The use of Iranian-designed and -produced one-way attack ‘kamikaze’ UAVs is a growing trend in the region. They are actively used by Iran and their proxies against coalition forces in the region, to include targets in Saudi Arabia and Iraq.”

Credit: US Navy

In fact, Iranian-made UAVs are now being used by Iran’s Yemen-based Ansar Allah (Houthi) rebel proxies further afield than Saudi Arabia (with whom the Houthis are engaged in a civil war). Following the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas conflict in Gaza in October 2023, and seemingly in an effort to stretch the crisis and US commitments, in November 2023, the Houthis began using UAVs – amongst other systems – to target commercial ships sailing in the Gulf of Aden/Bab-al-Mandeb/southern Red Sea corridor.

CENTCOM reported that, on 15 November 2023, the US Navy (USN) Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Thomas Hudner had engaged and shot down a UAV that originated from Yemen and was heading in the ship’s direction. Since then, the Houthis have continued to launch UAVs, alongside uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) and anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), against commercial and naval ships sailing in the region.

Trends

The use of such capabilities in lower-end ‘grey zone’ attacks (in the Iranian case) and higher-end combat attacks (in the Houthi case) demonstrate how rogue and non-state actors are currently able to harness new technology faster than Western armed forces. Western armed forces must go through regulation when introducing technology innovation, to reduce risk when bringing in new capability; rogue actors may see value in taking on more risk to get ahead of the game.

Nonetheless, rogue actors’ use of UAVs – especially in one-way attack operations – is a step beyond current concepts of operation (CONOPS) Western military forces have been broadly considering for using such capability. Indeed, although some Western forces have actively been developing capability to arm uncrewed systems including UAVs with offensive weapons, continuing ethical concerns over deploying kinetic capability onboard uncrewed systems have, to date at least, served to focus development on non-kinetic roles like intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR).

It is also worth pointing out that, while Western forces have been assessing what weapon system options may offer strike capability for uncrewed systems such as UAVs, rogue actors have been keeping things more simple by just using the vehicle itself, fitted with explosives, to provide the strike capability. While Western industry is no stranger to this concept, with purpose-built loitering munitions (LMs) becoming increasingly common, their adoption has nonetheless been a step behind that of rogue actors.

Credit: US Navy

CENTCOM’s use of the word ‘kamikaze’ draws the link between this capability approach and operational methods used by Japan’s armed forces in the Second World War. Beginning at Leyte Gulf in October 1944, Japan used crewed aircraft in kamikaze attacks to devastating effect against USN ships in battles across the Pacific.

Prior to Japan’s use of kamikaze tactics, Germany had, since June 1944, been launching V1 ‘Doodlebug’ flying bombs – the forerunners of contemporary cruise missiles – against targets in the UK. In the 1980s, cruise missile evolution included the use of Exocet missiles in the Falklands War and Styx missiles in the Iran-Iraq War, before Tomahawk cruised into view as the uncrewed, stand-off strike ‘game changer’. Tomahawk’s own evolution has included, at two points, development of an anti-ship capability. However, Tomahawk and other weapons like it are state-of-the-art, high-end, stand-off systems, and are priced accordingly.

What UAVs are clearly offering to rogue actors is an affordable and readily-available means of generating effect. Such affordability and availability means they can also be acquired in large numbers. Moreover, the international responses to both the Iranian attacks in the Gulf and the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea underline the strategic-level impact that such affordable capability can have when used in the right context. The fact that the Houthi threat to international shipping has prompted the United States and the United Kingdom to conduct kinetic strikes into Yemen against Houthi targets, despite the risk of this escalating tensions across the Middle East region, underscores the point.

Timelines

In the wake of the M/V Mercer Street attack, US experts concluded that debris retrieved from the ship demonstrated that the UAV was Iranian-designed and produced, with CENTCOM concluding that “Iran was actively involved in this attack.” It is worth noting that the United States deployed a UAV to the ship’s position to support the international community’s incident response. This response included forensic assessment confirming, according to CENTCOM, that the UAV was carrying explosives.

Iran had presaged development of this capability. Back in October 2018, the US Naval Institute reported that USN warships in the Gulf were being regularly overflown by Iranian UAVs. In September 2020, a UAV overflew the USN aircraft carrier USS Nimitz as the ship transited the Straits of Hormuz. In these earlier instances, surveillance appeared to be the name of Iran’s game. However, Iran’s capability and intent has clearly evolved.

Following the M/V Mercer Street attack, in November 2022 the oil tanker M/V Pacific Zircon was struck and damaged by an Iranian Shahed-136 one-way UAV. According to a March 2023 report by the Middle East Institute, Shahed-136 has a range of up to 2,500 km.

Credit: US Navy

In June 2023, a US official said Iran had tested a UAV in a kamikaze-type role in the Gulf, against a barge located several miles offshore, and had launched another missile or UAV without issuing notice to mariners in the area, media reported. The official was quoted as saying the UAV test was “essentially practicing hitting merchant vessels”.

These incidents foreshadowed the spike in attacks observed during late 2023 and continuing into 2024:

- In late November 2023, aircraft from the USN’s Nimitz class aircraft carrier USS Dwight D Eisenhower intercepted an Iranian UAV that was, according to CENTCOM, “operating in an unsafe and unprofessional manner” close to the carrier while the ship was conducting flight operations in the Gulf. The UAV got within 1.37 km (1,500 yards) of the carrier, with repeated warnings ignored, US Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) said in a statement.

- On 23 November, across the region in the Red Sea, the USS Thomas Hudner was back in action. A CENTCOM statement said the ship “shot down multiple one-way attack drones launched from Houthi controlled areas in Yemen”.

- On 29 November, Arleigh Burke sister ship USS Carney – also sailing in the Red Sea – shot down a UAV that was launched from Yemen and was heading towards the ship. CENTCOM identified the UAV as an Iran-produced KAS-04 system.

- On 3 December the USS Carney was back in action, shooting down three single UAVs in three separate incidents. The UAV attacks were interspersed with ASBM launches.

- On 10 December, the French Navy FREMM frigate FS Languedoc shot down two UAVs.

- On 14 December, another Arleigh Burke destroyer became involved. USS Mason shot down a UAV, launched from Houthi-controlled territory, which was heading directly for the destroyer, which had gone to help a tanker that was being harassed by Houthi forces in skiffs. In the incident, the Houthis also launched ASBMs at the destroyer.

- On 15 December, a UAV conducted a successful attack in the Red Sea, striking the container ship M/V Al Jasrah. The ship’s crew put out a resultant fire, and the ship was able to continue its transit.

- On 16 December, USS Carney was back in action again, this time successfully engaging 14 UAVs in what CENTCOM referred to as a “drone wave”. “The UAVs were assessed to be one-way attack drones,” CENTCOM added.

- On 18 December, the tanker M/V Swan Atlantic was attacked by a one-way UAV and an ASBM, and was hit.

- On 23 December, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Laboon got involved, shooting down four incoming UAVs. On the same day, two tankers were attacked by a UAV each, with one hit and one miss.

- On 26 December, USS Laboon teamed up with F/A-18E/F Super Hornet strike aircraft from USS Eisenhower to shoot down 12 one-way UAVs, three ASBMs, and two ASCMs. These attacks took place over a 10-hour period, CENTCOM said.

- On 29 December, USS Mason shot down a UAV and an ASBM.

- On 6 January, USS Laboon was the first USN shooter back in action in 2024, bringing down an inbound UAV on 6 Jan.

- On 9 January, perhaps the biggest attack to date took place, with 18 UAVs, two ASCMs, and one ASBM shot down in what CENTCOM referred to as a “combined effort” involving USS Laboon, USS Mason, sister ship USS Gravely, the UK Royal Navy Type 45 destroyer HMS Diamond, and F/A-18s from the USS Eisenhower.

- On 17 January, a UAV struck the bulk carrier M/V Genco Picardy in the Gulf of Aden. CENTCOM noted that some damage was reported, but that the ship remained seaworthy and underway.

In a press briefing on 4 January 2024, Vice Admiral Brad Cooper – the USN’s Bahrain-based, triple-hatted commander of US NAVCENT, US Fifth Fleet, and the USN-led Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) maritime security partnership – said that the regularity of the attacks and numbers of missiles involved presented a complex threat for the naval ships gathered, under the multinational Operation ‘Prosperity Guardian’ (established on 18 December 2023), to defend against the Houthi strikes, but that the response had been effective. “It’s a very active defensive role,” he said.

Credit: Crown Copyright 2024

However, some of the operational evidence may indicate that Iran (or perhaps the Houthis) have not yet fully optimised the ‘game-changing’ capability that uncrewed systems such as UAVs are perceived to offer. Few of the UAVs launched across Red Sea waters appear to have reached their apparent targets; those that have done so appear to have inflicted only limited damage, at least in that the ships do not appear to have been stopped from continuing on. While perhaps Iran may have decided to take more risk with the capability to create a threat through fear of potential attack – and to some extent this has been successful, given that some shipping companies have opted to re-route their ships southward around the African continent – the military effectiveness of the Iranian/Houthi UAV capability does not yet appear to be as potent as it could be.

This is demonstrated too in the tactical employment of the systems, when launched in numbers. Iranian fast-attack surface craft operating in the Gulf routinely harass naval and commercial shipping by swarming around them in an apparently co-ordinated manner. Swarm tactics are a central element of Western discussion regarding harnessing the potential benefits of the mass that uncrewed systems can bring. Yet, despite launching weapons in large numbers towards the Red Sea shipping lanes, there is no public evidence to date that such weapons have been operating in an integrated, co-ordinated manner. US officials have been clear in using the word ‘waves’, as opposed to ‘swarms’, when characterising the nature of the larger-scale strikes.

A lack of integrated ISR and command, control, and communications (C3) capabilities could be a primary explanation for why swarm tactics have not yet been used, and could also explain the apparently limited targeting effectiveness. Despite these limitations, the Houthi attacks have endured, and still constitute a threat in being. In his press briefing, Vice Adm Cooper said “We are certainly mindful of the continued threat, and expect the Houthi attacks may continue.”

The threat has also expanded. The Red Sea crisis has seen the use of USVs. While the Houthis have modified rigid-hull inflatable boats – either crewed or uncrewed – with explosives to attack naval ships in port and commercial and naval ships at sea before, the current crisis saw the first use of a bespoke USV in the region. “I’d characterize the USV incident as the use of a new capability,” said Vice Adm Cooper, noting, “The introduction of a one-way attack USV is of concern.”

Wider demonstration

Iran has also found other routes by which to test, develop, and demonstrate its UAV capability. Writing for the Gulf International Forum in November 2023, Giorgio Cafiero – a US-based analyst and expert covering Gulf security matters – noted that, through its supply of UAVs to Russia that Moscow has used to some effect in its war with Ukraine, Iran’s capacity to develop and deliver such capability has been tested and demonstrated. Indeed, the Russo-Ukraine war is acting as a testing ground for Iran’s UAV capability, Cafiero continued. Citing a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report on Iran’s UAV developments, Cafiero wrote “As Iran’s role as an exporter of unmanned technology becomes more robust, it may well acquire ‘future clients’.”

Credit: US Navy

Moreover, provision of such capability has made Iran “increasingly useful” to Russia, Cafiero explained, giving Iran greater leverage in its relationship with Russia while also providing revenue for Tehran at a time when the country is under US-led international sanctions.

Iran’s technology development also has wider implications for Gulf regional security: Cafiero said that Bahrain, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) “have long perceived Iran’s drone and missile programmes as an enormous danger to their security”: moreover, he added, the transfer of such capabilities to non-state actors across the region confers plausible deniability for Tehran. Iranian-produced UAVs have been used in various attacks across the region, including in Saudi Arabia in September 2019 and the UAE in September 2022.

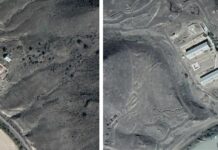

Reports also note Iran’s development of two naval ‘drone carriers’, designed as host platforms for its UAV capability. According to the Middle East Institute report, a sea-launched UAV capability would give Iran “strategic depth, greater strike options, and the means to threaten adversaries from the Gulf of Aden to the Gulf of Oman [and] may influence shipping patterns across the Arabian Sea and into the Indian Ocean”.

Iran’s UAV capability, alongside a selection of other weapons, enables Tehran – for example, when distributing these capabilities to the Houthis in Yemen – to cast a shadow over shipping and shape events in both the Gulf and the Gulf of Aden/Bab-al-Mandeb/Red Sea corridor, two of the world’s most important maritime choke points.

Dr Lee Willett