In the decades following the end of the Cold War, most US investment in integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) had been on large, non-mobile systems. Manoeuvre formation IAMD was reduced and units removed from the order of battle. Other NATO members made similar decisions. Elsewhere, countries that continued to field new ground-based air defence (GBAD), including Russia and Israel, were concerned with defending the homeland against missile or rocket threats.

Today, for the US, NATO and countries throughout the world, manoeuvre formations’ IAMD capabilities, have become near-term priorities, reflecting the wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Nagorno-Karabakh, Yemen, Syria and Iraq. New technologies and systems are being developed to enable future enhanced capabilities.

Manoeuvre formations’ IAMD remains largely service-specific, rather than being fielded through joint or coalition efforts. Looking at examples of programmes by the US Army and Marine Corps and some by European/other NATO countries, near-term capabilities have already been added to their force structures while at the same time, creating infrastructure – including sensors and network connectivity – that can be used with emerging technologies. The war in Ukraine cannot be ignored, showing manoeuvre formation IAMD’s capabilities and limitations.

A changed environment

Mobile, network-connected, survivable and interoperable systems are objective capabilities for manoeuvre formation IAMD. Today, there are fewer brigades and divisions than during the Cold War, with fewer opportunities for mutual support, and these operate dispersed over wider areas. Operational tempos have increased, and decision times reduced.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have demonstrated an ability to transform current battlefields. The counter-UAV (C-UAV) mission overlaps with IAMD. For example, the US Army has made air defence units responsible for defeating Group 3 and larger UAVs, include loitering, attack drones and swarming UAVs. The need for indirect fire protection capacity (IFPC) underlines that IAMD requires a self-defence capability as well as defending other units.

Credit: US Army/Georgios Moumoulidis

Technologies such as low-cost interceptors, high energy laser (HEL) and high-power microwave (HPM) are currently operational for C-UAV and IFPC missions. The deployment of mobile HEL weapons in the 300 kW power class, currently being developed in prototype form, will provide a cruise missile defence capability. High-level automation, in operational use for decades with GBAD and IFPC systems, will likely see capability expansion and wider application through the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI).

Prioritising IAMD – the US Army

“We’re going to need organic air defence with our fires, our manoeuvre units”, US Secretary of the Army Christine Wurmuth said at a talk in Washington on 19 September 2023. The US Army ranks IAMD as number four of its six top force modernisation priorities, with four major lines of effort: Manoeuvre-Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD), Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC), Army Integrated Air and Missile Defense Networked IAMD (AIAMD) command and control (C2), and Lower Tier AMD Sensors (LTAMDS). Elements of all of these were delivered to operators before the end of 2023.

Linking IAMD systems together with the US military’s Joint All Domain C2 (JADC2) architecture, AIAMD C2 capabilities include the Northrop Grumman Integrated IAMD Battle Command System (IBCS), which started initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E) in 2022. In 2023, it was approved for full rate production (FRP) and, using low-rate initial production (LRIP) systems, achieved initial operational capability (IOC). While IBCS is currently operational in conjunction with the Army’s larger Raytheon MIM-104 PATRIOT-equipped units, the integrated fire control networks (IFCNs) that it enables can, in the future, include manoeuvre formation IAMD. “IBCS transforms the battlespace by fusing data from any sensor to create a picture allowing commanders to see the battlespace,” Rebecca Torzone, vice president and general manager, combat readiness for Northrop Grumman, said on 13 April 2023.

Intended as the primary IAMD sensor for Army manoeuvre formations, deliveries of the Lockheed Martin AN/MPQ-61A4 Sentinel active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars started in 2022, and is scheduled to achieve IOC in 2025. Providing 360° coverage, it will equip Army M-SHORAD and IFPC battalions. Raytheon AN/MPQ-64A3 Sentinel radars are being upgraded and will serve into the 2030s. These are capable of IFPC missions and are also used in conjunction with the Kongsberg Defence/Raytheon NASAMS, currently being used in combat by Ukraine.

Credit: RTX

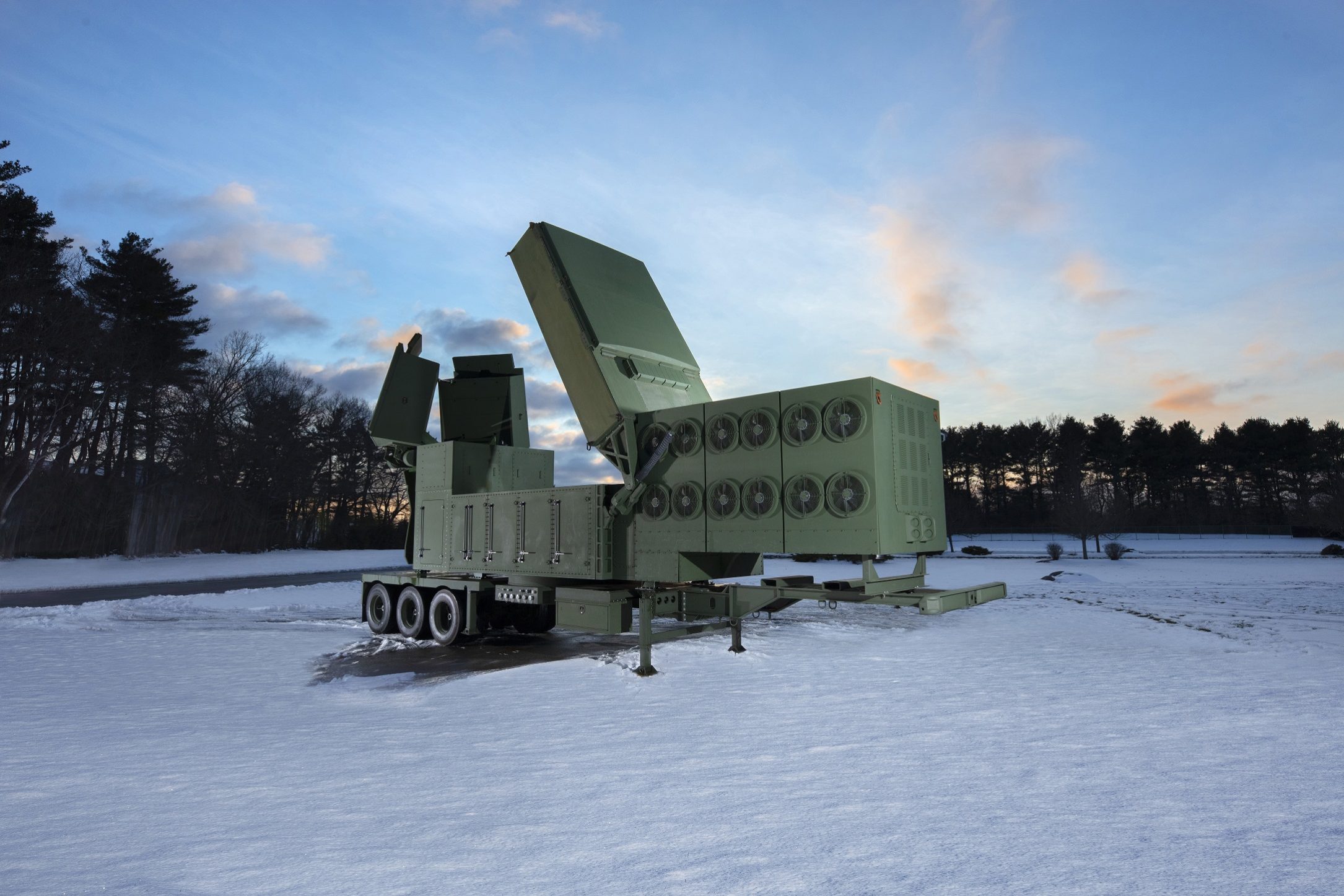

Systems – such as PATRIOT – normally do not manoeuvre with troops. Through being networked, their sensors are able to contribute to overall situational awareness, not limited by being ‘stovepiped’ with a specific battery. The Raytheon LTAMDS ‘GhostEye’ family of AESA radars is undergoing developmental testing, which will run through 2024. LTAMDS is the same size as the older AN/MPQ-53 radar used by PATRIOT, but with over twice the power. The medium-range variant of the Ghost Eye family, known as Ghosteye MR, has been integrated with NASAMS.

M-SHORAD

The M-SHORAD program is central to upgrading US Army manoeuvre formation IAMD, using an incremental approach using existing systems while investing in new armament options.

Replacing part of the US Army’s current force of Boeing AN/TWQ-1 Avenger self-propelled surface-to-air missiles (SAM) systems, the M-SHORAD Increment 1 design was developed as a rapid response programme that started in February 2018 and delivered prototypes for testing 19 months later. It uses the General Dynamics Land Systems Stryker A1 8×8 wheeled AFV platform, armed with Lockheed Martin AGM-114L Hellfire Longbow missiles and Raytheon FIM-92K Stinger SAMs. Its Northrop Grumman XM914 30mm cannon will fire the currently under development XM1223 Multi-Mode Proximity Airburst (MMPA) proximity round for C-UAV purposes. Its Leonardo DRS mission equipment package includes the RADA USA Multi-mission Hemispheric Radar (MHR) and networked connectivity.

The current US Army requirement is for 162 M-SHORAD Increment 1s, 144 of which will equip four division and corps-level air defence artillery (ADA) battalions. The first unit, 5th Battalion of the 4th (5/4th) Air Defense Artillery Regiment (ADA), stationed in Germany, received its initial platoon of M-SHORAD Increment 1 vehicles in 2021. A second battalion, the 4/60th ADA, was activated at Fort Sill, Oklahoma in April 2022, as the organic ADA battalion of the 1st Armored Division. The third and fourth M-SHORAD battalions will also be part of US-based divisions.

The M-SHORAD Increment 2 Multi Mission High Energy Laser (MMHEL) Guardian system has been developed by the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Organization (RCCTO). It retains the Increment 1’s vehicle and mission equipment but is armed with a Raytheon 50 kW laser, intended primarily for the C-UAV and IFPC missions. A prototype system participated in the Army’s 2015 Manoeuvre and Fires Integrated Experiment (MFIX). The first Increment 2 vehicle was delivered in 2022, the first four-vehicle platoon of prototype vehicles was delivered to the 4/60th ADA in September 2023. In live-fire testing at Fort Sill and the Yuma Proving Ground Arizona in 2023, Increment 2 systems destroyed Group 1 and Group 3 UAVs. Increment 2 is scheduled to achieve IOC in fiscal year (FY) 2025.

Credit: RTX

M-SHORAD Increment 3 is due to replace Stinger with the proposed Next Generation Short Range Interceptor (NGSRI). In 2023, the US Army issued contracts to Raytheon and Lockheed Martin for a competitive prototype fly-off for NGSRI. A production decision will be made in FY 2027, followed by procurement of up to 10,000 missiles. Congress has indicated a willingness to reprogramme funds to accelerate this program.

Until Increment 3 is available, Stinger production, which had halted, was restarted in 2020-21 and is to increase to 60 per month in FY 2025, some 50% greater than current levels. Stingers remaining in the US stockpile may be upgraded, along with many of which those used by NATO forces, especially Germany.

IFPC Increment 2-Intercept Block 1

The US Army plans to deploy eight IFPC battalions as division and corps-level assets, replacing the current Avenger and Raytheon Land-based Phalanx Weapons System (LPWS). The IFPC Increment 2 – Intercept Block 1 system was developed in response to limitations in the IFPC Increment 1, which was the Rafael Iron Dome interceptor system, as operated by Israel. Two Iron Dome battery sets were delivered to the US Army. In 2021, during an exercise, an Iron Dome battery deployed as part of the air and missile defence of Guam. The Iron Dome equipment, including 200 Israeli-produced Tamir missiles, was then leased to Israel for 11 months (with an option for subsequent purchase), when the Israel-Hamas War started in October 2023.

The Army decided, in September 2021, instead of procuring the Iron Dome system, to test the IFPC Increment 2—Intercept Block 1 system. This configuration will use the IBCS and include the Sentinel A4 radar, 16 Dynetics Enduring Shield Multi-Mission Launchers (MMLs) and 80 Raytheon AIM-9XB2 Sidewinder SAMs. Deliveries started in 2023 for developmental testing starting in early 2024, which may lead to production, following an operational assessment in FY 2024. The total requirement may include some 400 MMLs.

Credit: Dynetics

The Increment 2 system is intended have an IAMD capability, primarily against subsonic cruise missiles. The kinematics of the Sidewinder enables engaging a wide range of threats. In 2023, the Army asked industry for an interceptor capable of enabling the system to defeat supersonic cruise missiles. Increment 2’s integration with LTAMDS was tested in exercises in December 2023.

US Marine Corps MRIC

The establishment of the Marines’ 3rd Littoral Anti Air Battalion (LAAB) in 2022 provided the first of several new units that will provide overlapping IAMD, IFPC and C-UAS capabilities, planned to operate the Marines’ Medium Range Intercept Capability (MRIC). “MRIC is a middle-tier acquisition rapid prototyping effort, serving as a short-to-medium range air defence system [Editor’s note: despite being characterised here as short-to-medium range, Iron Dome’s Tamir missile in fact operates at VSHORAD ranges] that fills a crucial capability gap in the Indo-Pacific,” Lt. Col. Matthew Beck, the program manager, said at Quantico on 29 August 2023.

The Marines procured an Israeli-produced Iron Dome IFPC battery set, which provided the basis for the MRIC, successfully integrating it with their sensors and command and control (C2). The MRIC started live-fire testing in May 2022. Its capability in the IAMD role was demonstrated in June 2023 testing against cruise missile targets at White Sands Missile Range New Mexico, leading up to a planned September 2024 quick-reaction assessment that could put the program on course to start procurement in FY 2025.

Credit: David Isby

While MRIC testing has used Israeli-produced Rafael/Raytheon Tamir SAMs (as used by Iron Dome), operational versions will be equipped with the Raytheon SkyHunter, (a version of the Tamir that will be interoperable with it), a US-designed trailer-mounted 20-round launcher, the Marine’s Common Aviation Command Control system and the Northrop Grumman AN/TPS-80 Ground/Air Task Oriented Radar (G/ATOR) AESA radar. MRIC deliveries are planned to start in June 2025. Three batteries – one for each Low Altitude Air Defence battalion – could be delivered by FY 2028, with a potential total procurement of up to 44 launchers and 1,840 missiles.

“A striking example of successful acquisition support to Force Design 2030 execution can be seen in our Ground-Based Air Defence system,” Stephen Bowdren, the Marines’ Program Executive Officer for Land Systems, said at Quantico on 29 August 2023. “In a very short period of time, we’ve established a comprehensive suite of capabilities designed to counter the full range of aerial threats to Marines.”

NATO

The meeting of NATO defence ministers on 21 October 2021 took action on a range of IAMD-related capabilities. Modular GBAD aims to integrate medium and short range IAMD using C2 modules with a plug-and-play capability; Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, The Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, UK, Norway, Poland, Portugal and US are members. The GBAD C2 Layer (Denmark, Italy, Portugal, Spain, UK and US) provides interoperable IAMD fire distribution centers (FDCs) at the battalion and brigade level, directly enhancing manoeuvre formation capabilities. Rapidly Deployable C-RAM, developing interoperable IFPC, includes Norway, Poland, US, Germany, Greece, Hungary, and the UK.

The 2022 NATO ministerial meeting saw 15 nations (with a further two to follow) sign up to the German-led European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI). Primarily focused on a framework for a multinational missile defence capability, it included provisions for integrating mobile SAM systems, notably the German-built Diehl IRIS-T family. Looking towards ESSI implementation, at the October 2023 NATO ministerial meeting, ten countries agreed to a framework for joint air defence system procurements (Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania and the Netherlands). Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia’s joint NASAMS and IRIS-T family procurements were announced in 2023.

CAMM

The MBDA UK Common Antiair Modular Missile (CAMM) family of SAMs, developed by the United Kingdom, shares features and components with the MBDA UK Advanced Short Range air-to-air missile (ASRAAM). The British Army had a long-standing requirement for a replacement for the Rapier SAM system, in service since the 1970s, and has procured the Sky Sabre system to provide the medium range air defence (MRAD) component of its Land GBAD program. It is the UK variant of the MBDA EMADS system; it is armed with the CAMM missile, uses the HX77 8×8 truck platform as the basis for mobile system components, and is provided with the Saab Giraffe Agile Multi-Beam (G-AMB) 3D multifunctional radar, and a Rafael Advanced Defense Systems Modular, Integrated C4I Air & Missile Defence System (MIC4AD) fire control centre, along with Link 16 and other tactical datalinks. Officially in service since December 2021, a Sky Sabre battery set is stationed in the Falkland Islands. Sky Sabre provides IAMD for 1 (UK) Division as part of 7th Air Defence Group, which has made rotational deployments to Poland.

Credit: MBDA

Poland has also been a major customer for the Land Ceptor, which has been integrated, by a partnership of MDBA and Poland’s PGZ-NAREW consortium, into the Mała Narew MRAD system. This includes Polish domestically-produced components, such as the Jelcz 8×8 truck platform as the basis for mobile system components, and the Zenit C2 system produced by PIT-RADWAR. Production in Poland is planned to include some 100 launchers and over 1,000 missiles. First deliveries took place in 2021. The first battery was equipped in September 2022, accelerated from the scheduled date of 2027 in response to the war in Ukraine. Batteries have been delivered to air defence units of the 16th and 19th Mechanised Divisions. A programme of ongoing Anglo-Polish cooperation on Sky Sabre was announced in March 2022.

Ukraine

The war in Ukraine has shown how both sides’ GBAD defend front-line units. The Ukraine Defence Contact Group, meeting at NATO headquarters in Brussels on 11 October 2023, pledged that “Zelensky can protect his cities and also protect his troops”, US defence secretary Lloyd Austin told journalists.

Credit: National Guard of Ukraine

In 2022, Ukraine’s manoeuvre formation IAMD relied on Soviet-era systems including the Osa (SA-8 Gecko), Buk (SA-11 Gadfly – which was apparently the most effective) and Tor (SA-15 Gauntlet) SAM-equipped units. Both Ukraine and Russia used MANPADS and gun systems for manoeuvre formation defence, with 19 Russian and 11 Ukraine jet aircraft reportedly lost to these weapons in 2022. Ukraine has continued to rely on MANPADS – with Soviet-era types reinforced by systems such as the Stinger, Piorun, Starstreak HVM, Mistral, and various cannon-based systems for manoeuvre formation IAMD, especially in the 2022 fighting in Mariupol and Donetsk sectors, outside of the cover of longer-ranged SAMs.

In December 2023, it was reported that Ukraine had moved Patriot fire units forward, allowing them to shoot down Russian fighters in the Kherson sector. Russian air attacks on Ukraine’s front-line units relied increasingly on attack helicopters, which suffered substantial losses through 2023 despite using air-to-surface missiles such as the 9M127 Vikhr, which enables helicopters to engage targets from outside MANPADS range.

By 2023, international support provided Ukraine an unprecedented range of IAMD systems that, despite limitations in training, lack of standardisation and challenges to sustainment, have deterred Russia’s numerically and qualitatively superior airpower. Ukraine’s forces have demonstrated remarkable adaptability, as the numbers of aircraft and missiles destroyed indicate. By 2023, the C-UAV and IFPC missions – the latter including self-defence by IAMD systems – have been seen as forward area priorities.

Most of Ukraine’s IAMD systems are used to defend cities and infrastructure throughout the country. Their effectiveness has led the Russians, starting as early as March 2022, to increase their reliance on missiles. Air Force spokesperson Yurii Ihnat was quoted in the Kyiv Independent on 21 December 2023 that Russia had launched some 7,400 missiles at various targets in Ukraine, reducing Ukraine’s SAM stockpiles to a critical level.

Credit: Ukrainian Army

Ukraine’s forward area IAMD has been attacked by jammers, long-range artillery cued by UAVs, and loitering munitions – including first-person view (FPV) drones. Loitering munitions, along with larger strike UAVs had previously proven effective against Armenia’s relatively old SAM systems during the 2020 Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. While Soviet-era suppression of enemy air defences (SEAD) weapons including air-launched Kh-31P (AS-17 ‘Krypton’) and Kh-58 (AS-11’Kilter’) anti-radiation missiles (ARMs) and the surface-to-surface Tochka (SS-21 ‘Scarab’) ballistic missiles have been used in combat, their damage appears to have been concentrated on fixed targets such as static air defence radars; IAMD assets able to displace and operate from dispersed camouflaged locations were often able to survive.

The future

The importance of interoperability for joint and coalition operations has been emphasised through the ongoing multinational deployments to NATO’s eastern members, in exercises such as NATO’s Formidable Shield and experiments such as the US Army’s Project Convergence. Manoeuvre formation IAMD is, of necessity, multinational; sensor and fire control networks must be able to reflect this.

Threats, such as attack drones, are cheap and plentiful while current SAMs are expensive, and SAM launchers are vulnerable to direct attack. The introduction of specialised C-UAV and IFPC systems will not remove IAMD’s need to defeat these threats. Looking beyond the near-term future, technologies such as HELs are being ‘scaled up’ to enable them to supplement SAMs in carrying out the IAMD mission.

Ukraine has demonstrated that IAMD needs to be able to upgraded quickly, integrating new missiles, launchers, sensors. In this regard, Ukraine has adapted ASRAAM as a SAM, and integrated the IRIS-T missile with the NASAMS launcher. While the initial NASAMS deployment in Ukraine was for the defence of Kyiv, they have also been used to defend forward area troops. The Raytheon RIM-7 NATO Sea Sparrow Missile (NSSM) and AIM-9M Sidewinder were integrated with the Buk system already in Ukraine’s inventory to create the ‘FrankenSAM’ launch vehicle which went into action in January 2024. The need to upgrade software will only increase; AI and cyber warfare will become increasingly important.

Credit: NATO

Outside NATO, other countries are investing in IAMD capabilities, including Austria, Taiwan and Australia, where the army identified air and missile defence as a priority mission in their 2023 Defence Strategic Review. Armenia, which in 2020 lost many of its SAM systems in combat, announced in October 2023 it would replace them by acquiring French-built Mistral VSHORAD missiles.

David Isby