The US Air Force (USAF) is continuing to modernise its Falconer command and control (C2) architecture, but does the system have a long-term future as the Pentagon embraces new warfighting doctrines?

In August 2022, the USAF awarded a USD 319 million contract to SAIC, for sustainment and modernisation of the AN/USQ-163 Falconer C2 system, which the USAF uses to manage air operations. SAIC is part of ongoing efforts to revamp the overall Falconer architecture. The USAF’s own literature describes Falconer as “a system-of-systems that incorporates numerous third-party software applications and commercial off-the-shelf products.” Falconer assists theatre air and missile defence, “pre-planned dynamic and time sensitive multi-domain target engagement operations,”, plus intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) resources management.

The AN/USQ-163 provides a vital, operational C2 capability to support air, and wider joint, operations. Political direction flows from the US President, as commander-in-chief, and the administration, notably with the Secretary of Defense. US geographical combatant commands are responsible for the C2 of any conflict or contingency and are assigned this responsibility depending on where the situation is occurring. To this end, a geographical combatant command may take responsibility. Alternatively, Cyber Command, Space Command, Special Operations Command, Strategic Command and/or Transportation Command could take responsibility should the situation demand. The air dimension of any contingency will be the responsibility of the Joint Force Air Component Commander (JFACC), who will exercise command from the Combined Air Operations Centre (CAOC), which is where the AN/USQ-163 system resides.

A key role of the CAOC and Falconer is to draft the Air Tasking Order (ATO). In a nutshell, the ATO provides the ‘sheet music’ for all air operations and will cover the following 24 hour period. The author has seen ATOs in the past and can attest to them running to hundreds of printed pages. The ATO details a myriad of missions from combat air patrol and tanker orbits to close air support provision and battlefield interdiction. Put simply, if it flies, it is detailed in the ATO. The ATO translates the intent of the strategic political leadership and the operational commanders into a series of air actions to support this.

Credit: USAF

Software upgrades

Efforts to modernise Falconer began just after the turn of the century. In 2003, the USAF launched its Air Operations Centre-Weapon System (AOC-WS) enhancement for the AN/USQ-163. At that time, the AOC-WS project was limited in scope, with limited funding available; improvements to the existing architecture tended to be small but were urgently needed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the strategic exigencies of the time, these improvements tended to be restricted to the Falconer system equipping US Central Command. As it does today, Central Command (CENTCOM), was responsible for combat operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Falconer is currently being enhanced with the AOC-WS Block-20 software package. The USAF had planned to upgrade the AOC-WS via the Block-10.2 software modernisation, but this was cancelled. As a result, Block-20 is the first major AOC-WS software upgrade since the earlier Block-10.1 modernisation. Block-10.1 remains the current software standard for Falconer pending the full Block-20 rollout. The modernisation path for Falconer calls for Block-20 software and capabilities to be added incrementally to the current architecture. Falconer will thus have a ‘hybrid’ configuration combining some of the legacy Block-10.1 capabilities with selected Block-20 features before fully migrating to the latter status. Block-20 features will be added to the AOC-WS via what the Air Force calls Agile Release Events (AREs). Adornments added via Block-10.1 included mechanisms to swap legacy hardware out of Falconer, allowing their replacement with new systems relatively easily. Other enhancements included improving overall joint interoperability between Falconer and other operational/strategic level C2 systems.

Work on the Block-20 standard began in 2017, according to the Air Force. The service’s official documents state that the effort is being led by the USAF’s Kessel Run Experimentation Laboratory (KREL), opened in 2018, to “carry out the development of next-generation combat software” in the USAF’s own words. Star Wars fans will know the Kessel Run as a smuggling route mentioned in the original 1977 Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope film. KREL is managed by the Air Force Life Cycle Management Centre’s (AFLCMC) Battle Management Directorate. The directorate’s home is Hanscom Air Force Base in Massachusetts, while KREL is in nearby Boston. The AFLCMC’s Detachment-12, also located at Hanscom, has developed and is sustaining the AOC-WS Block-20 software. Detachment-12 has a satellite facility at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, which coordinates the delivery of the Block-20 software and provides associated sustainment and helpdesk facilities.

Alongside SAIC, the Air Force says that Raytheon is involved in the Block-20 update provision. SAIC was approached regarding its responsibilities in the Block-20 effort but the company declined to comment. What has been disclosed in the public domain is that SAIC is working as the systems integrator for the Block-20 initiative. The Air Force took a similar stance, saying that it had nothing more to add to information already available in the public domain regarding Block-20.

Credit: USAF

The AOC-WS improvements for Falconer are being realised through the use of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software and hardware, according the Air Force. While COTS software and components are supporting the system’s digital voice and data communications infrastructure, the US government is furnishing some proprietary software for air, space and cyberoperations planning, direction and monitoring. Government and COTS software and hardware are being fused with additional capabilities from unspecified third parties. These capabilities will fuse C2 data coming from other sources with Falconer’s, with improvements also allowing these data to be shared across several communications links. Links used by Falconer include the US Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Secure Internet Protocol Router Network (SIPRNET) and Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communication System (JWICS). SIPRNET is essentially a secure equivalent of the internet, carrying Classified and Secret data. JWICS, meanwhile, is a secure intranet system carrying Top Secret information – the highest level of DOD security clearance.

Block-20 software

The Block-20 enhancements discussed above are being rolled out across the USAF’s regional Air Operations Centers (AOCs). The US Air Force maintains several regional AOCs, including the 601st AOC at Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida. The 601st AOC forms part of US Northern Command, as does the 611th AOC at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Alaska. US Southern Command is supported by the 612th AOC at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona. Outside the US, the 603rd AOC at Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany supports the US African and European regional commands. US Indo-Pacific Command has two regionals AOCs: The 607th located at Osan Air Force Base in the Republic of Korea and the 613th AOC at Joint Base Pearl Harbour-Hickam in Hawaii. The 609th AOC at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar supports CENTCOM.

Block-20 software releases began being fielded across these various Falconer systems from September 2022, according to the Air Force with initial upgrades made to the 609th AOC’s system at Al Udeid Air Base. Similar releases are being installed on the AOCs discussed above, with initial installations are expected to be finished by the end of 2024. Software releases have been accompanied by an exhaustive test and evaluation regime which has identified and fixed problems experienced with these releases. The scope of the Falconer Block-20 modernisation is impressive, with US government documents stating that the system already contains over 40 C2 applications, even before the modernisation is fully rolled out.

Credit: USAF

The exact status of the Block-20 enhancement is unclear. As noted above, the USAF and SAIC declined to provide any information to this effect. Does this mean that the programme is experiencing difficulties? Without definitive information from either organisation, it is impossible to say for certain, although a reticence to discuss the programme does raise questions. For example, an analysis published by the USAF highlighted concerns regarding its test and evaluation strategy for Block-20. The analysis noted that the Block-10.1 enhancement was fielded in 2022; that same year, the analysis stated that a “required test strategy [for Block-20]” had not yet been approved. More worryingly, it claimed that the Block-20 software “released to date lacks sufficient capabilities to support major combat scenarios and the sustainment, maintenance, and training processes would not adequately support a meaningful operational evaluation.” Although the Air Force had submitted a test strategy for Block-20, “critical comments have not been resolved.” Part of the problem might have been that the Air Force was moving Block-10.1 and Block-20 forward at the same time.

Unsurprisingly, for a software-based C2 system, cybersecurity is paramount, all the more so given that Falconer must be deeply networked to perform its tasks. According to the DoD’s own analysis, the Air Force had “conducted a cooperative vulnerability and penetration assessment” at an undisclosed AOC site concerning the Block-10 software release. The service also overhauled its Test and Evaluation Master Plan (TEMP) for Block-10.1 which the DOD approved in 2011. The report continued that, as of 2022, no TEMP plan for Block-20 existed. Block-10.1 was further reinforced via regular capability and maintenance ARE software upgrades. These AREs were drafted on the basis of Falconer testing and evaluation performed at the Ryan Centre located at Joint Base Langley-Eustice in Virginia. Similar development work has also been carried out by the 612th AOC at Davis-Monthan Air Base.

Multi-domain operations

Where does Falconer go beyond the Block-20 upgrade? With the Air Force staying taciturn on the Block-20 initiative to date, it is hard to say for certain. There is every possibility that a further, similar, large-scale upgrade may occur over the next 20 years beyond this most recent initiative. Unlike a traditional platform, the AN/USQ-163 is a computerised system largely composed of hardware and software. Some of these components are bespoke and some are sourced as COTS elements. Within reason, it may be possible to continually improve Falconer by performing periodic software and hardware refreshes; such an approach could incorporate the ‘best and brightest’ software and hardware available into Falconer. On paper, this would appear to give the architecture a near-limitless lifespan. The continual improvement approach may also be significantly less expensive than acquiring a completely new system. Even if an AN/USQ-163 replacement is procured, this too would need to be continually refreshed throughout its life.

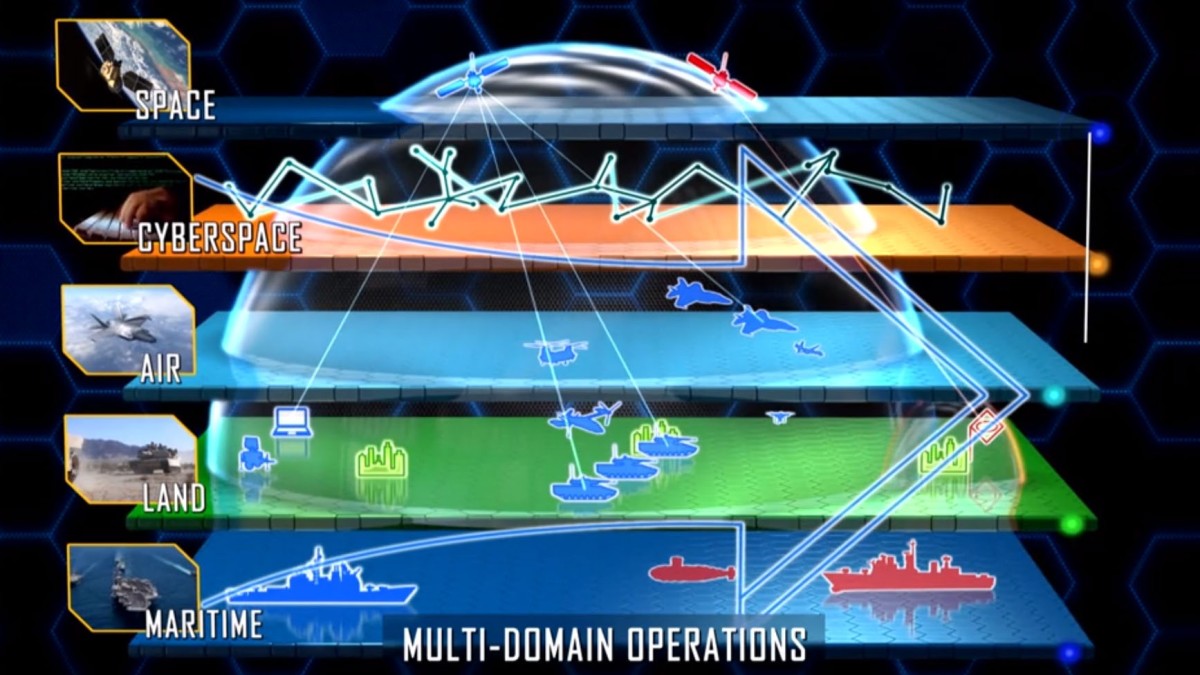

Over the longer term, Falconer will face distinct technological challenges that it must accommodate, hence no doubt necessitating further upgrades beyond Block-20. Perhaps the most vexing is the US Air Force embracing the multi-domain operations (MDO) approach heralded by the DoD. MDO is the Pentagon’s overarching doctrine to defeat peer- and near-peer adversaries. The rationale behind MDO is to ensure that one’s own forces take better quality and more timely decisions than one’s adversary. The MDO concept stresses navigating the famed observe, orient, decide and act (OODA) loop faster than their opponents, by making better decisions. MDO manifests itself in the DoD’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) system.

Credit: US Army Training Support Center

JADC2 is a collective term for a raft of DOD efforts across all the US armed services to realise the inter- and intra-force connectivity of all assets supporting any operation. Assets include all personnel, platforms, weapons, sensors, installations, bases and capabilities. JADC2 also places a premium on cloud computing. So-called ‘Combat Clouds’ will be the repository where tactically, operationally and strategically relevant data reside. These clouds will be rapidly accessed by those who need it. Each of the US armed services are configuring their C2 systems to ensure they are JADC2-compartible. The US Army is working towards this via Project Convergence. The US Navy’s effort is known as Project Overmatch, while the Air Force is forging ahead with the Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS).

How does Falconer fit into the Air Force’s ABMS architecture and the DOD’s overall JADC2 vision? It may not, according to a 2022 publication entitled Advanced Battle Management System: Needs, Progress, Challenges and Opportunities Facing the Department of the Air Force. The report was edited by Ellen Y. Chou, board director of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Input was received from the Air Force’s ABMS committee and the USAF Studies Board, among others. The study paints a worrying picture. Referring to the Block-20 initiative, the report warns that “(w)hile progress is being made, notable challenges remain with the current AOC design and construct”.

One area of concern is that the system’s underlying C2 architecture is not fit “to meet current operational and technological threats or support an accelerated pace of planning”. These alleged shortcomings are present despite the Block-20 initiative, the report argues. An additional cause of concern was the extent to which Falconer can work with the MDO doctrine and its JADC2 manifestations: “It was clear that the AOC system of systems architecture … would not support a transformation over time, because the inherently outdated technology and architecture utilised by the current system is unable to be restructured.”

In short, it appears that the AN/USQ-163 in its current guise may simply not be fit for purpose over the long term. “It is moreover evident, even without a JADC2 … that the Air Force requires an innovative and revamped AOC to interoperate with the new US Space Command and US Space Force operating systems and to meet broad operational challenges from adversaries seeking to counter US military advantages.” With these shortcomings highlighted, the USAF clearly has important decisions to make on the future of Falconer. Can additional life be wrung out of the AN/USQ-163? Or will a new architecture be needed to provide the Air Force with the C2 tools it needs for future battles? Only time will tell.

Thomas Withington