Naval warfare in the 21st Century is marked by potent new categories of offensive weapons and tactics, as well as upgrades to traditional weapon types. Fleet protection technologies must adapt to meet these new and enhanced threats.

The current threat picture

Conventional maritime threats posed by warships, submarines and aircraft abide. Technological enhancements – including stealth attributes, faster weapon systems and improved sensors – make these maritime attack platforms even more potent. Moreover, asymmetric threats have become well-established. These include suicide attacks using explosives-laden boats, and swarm attacks by missile-armed fast craft. High-end threats include so-called ‘carrier killer’ ballistic missiles such as the Chinese DF-26B and hypersonic anti-ship missiles (ASMs) such as the DF-27. While the accuracy and effectiveness of such weapon systems are the subject of debate, their potential to target high value large vessels such as aircraft carriers or amphibious warships must be taken seriously. The same holds for more conventional ASMs such as air, surface and shore launched cruise missiles. The range, accuracy and stealth attributes of such missiles are being enhanced in arsenals across the globe. Their potential was demonstrated in April 2022 through the sinking of the Russian cruiser RFS Moskva by Ukrainian-produced R-360 Neptun ASMs.

Credit: Airbus

Unmanned aerial, surface and underwater vehicles (UAVs, USVs and UUVs) have emerged as a newer threat. While originally considered as reconnaissance or surveillance tools, they are now capable of carrying automatic weapons, short-range missiles, and torpedoes. Artificial intelligence (AI) is endowing them with autonomous attack capabilities and the ability to carry out swarming missions, potentially overwhelming and penetrating even major warships’ defences. Here, too, the Ukraine war serves as a wake-up call.

Another bellwether is the current standoff in the Red Sea. Here Houthi forces are tying down two international naval forces comprised of around a dozen major warships, including a US Navy aircraft carrier. During one attack on 30 January, 2024, a cruise missile launched from Yemen came within two kilometres of USS Gravely (DDG-107) before the destroyer shot it down with a close-in weapon system or CIWS. The capability of comparatively unsophisticated forces to pose a credible threat to the most advanced western fleets underscores the potential threat from the navies of major or even regional powers. A multi-tier approach to countering such threats is required.

Credit: US Navy

ISTAR as the first step in fleet protection

The first step in achieving fleet protection is detecting and identifying threats. This begins with surveillance satellites. After these, long-range maritime reconnaissance aircraft – both manned and unmanned – form the next tier of an effective Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance (ISTAR) capability. The Boeing P-8 Poseidon is arguably the most modern and capable large maritime patrol aircraft. It has an unrefuelled range of up to 1,200 nautical miles and can linger over a surveillance area for four hours on a typical mission (these parameters can be expanded through aerial refuelling). With a maximum altitude of 12,500 metres and a standard cruising altitude of 10,000 metres it observes large swaths of territory at a time. The sensor suite encompasses synthetic and inverted synthetic radar (SAR/ISAR), electronic support measures (ESM), electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors, and 129 sonobuoys carried in a rotary dispenser. This enables detection of the full spectrum of surface and submerged maritime targets down to the size of a deployed periscope. Five internal and four external weapon mounts permit direct engagement of surface and submarine targets by Harpoon ASMs, AGM-88 anti-radiation precision guided bombs, Mk 54 torpedoes, and mines. Alternately, targeting data can be relayed to friendly ships or aircraft.

Credit: US Navy

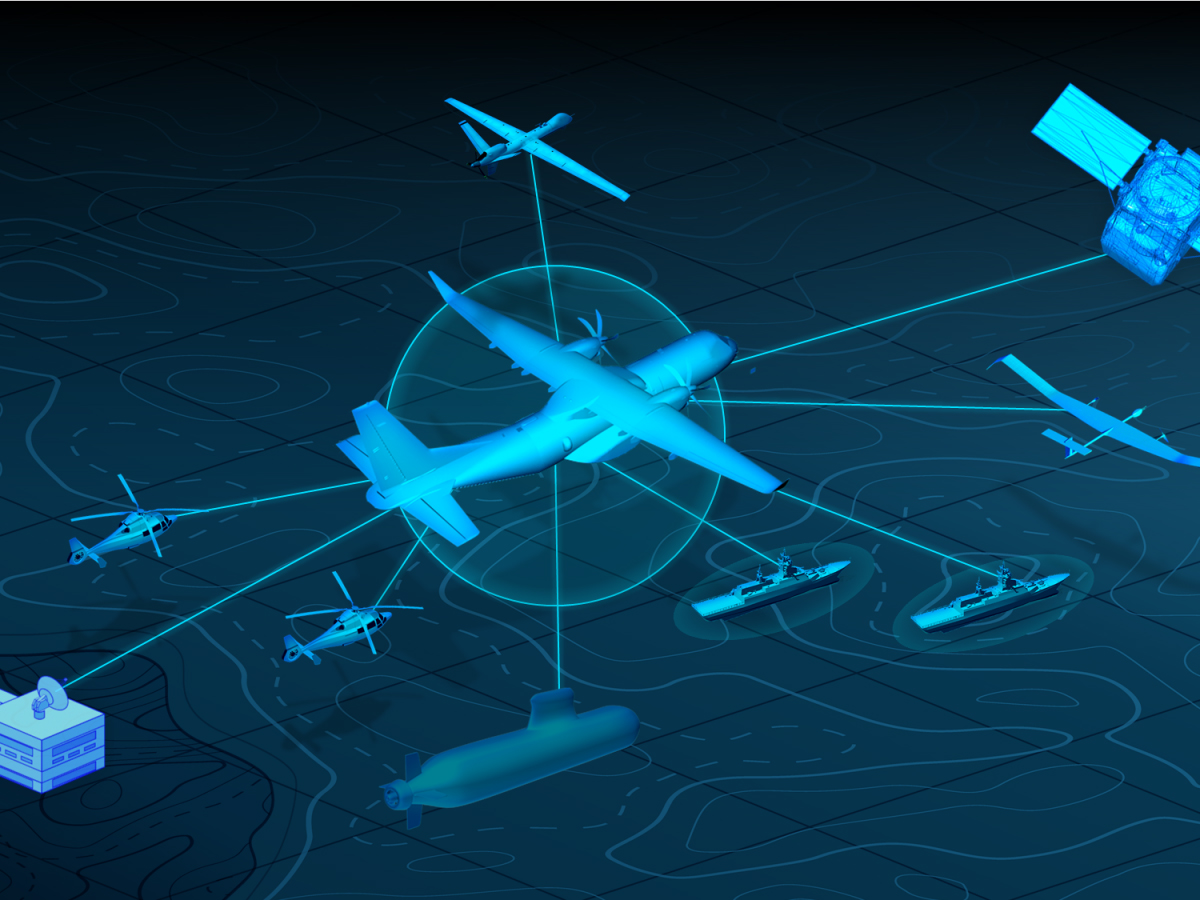

Medium sized aircraft are also potent ISTAR platforms. The Airbus C295 can be configured for unarmed maritime surveillance, armed maritime patrol or anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare (ASW/ASuW) missions. Its mission bay is equipped with the Fully Integrated Tactical System (FITS), which fuses data from the aircraft’s various sensors with input from external sources such as satellites, manned and unmanned aircraft, surface vessels and submarines. The resulting tactical operating picture can be shared across the network of friendly forces, and supports the aircraft’s deployment of torpedoes, ASMs, mines and depth charges. The unarmed C295 MSA (Maritime Surveillance Aircraft) variant achieves the highest mission endurance in its class, with up to 11 hours on station.

Credit: L3Harris

Unmanned systems integrate with and augment manned aircraft. The current state of the art is represented by the MQ-4C Triton UAV developed by Northrop Grumman. With a service ceiling of 15,400 metres and a 24-hour mission endurance, the aircraft has a mission range of 8,200 nautical miles; it is configured for global operations including the Arctic. During a single mission its high-fidelity radar, EO/IR and ESM sensors can sweep four million nautical square miles of ocean surface to locate and identify surface and subsurface threats to friendly forces, all while remaining undetected by hostile vessels.

Long-range ISTAR platforms can provide early warning but cannot replace shipboard sensors for detecting incoming threats at closer range (and guiding countermeasures to defeat these threats). All modern warships are equipped with multiple and overlapping sensors, including air and surface search radars, sonars and ESM. The US Navy is currently introducing the AN/SPY-6 Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR) on its Arleigh Burke Flight III destroyers. Details of the AMDR are largely classified, although Raytheon has previously stated that the new radar, when compared to the legacy AN/SPY-1, can detect objects “half the size at twice the distance.” The AMDR is scalable; variants could be fitted onto vessels ranging from large USVs to aircraft carriers. Other naval services are also updating radar capabilities. One example is the German Navy, which is replacing the SMART-L radars of its Sachsen class frigates with the TRS-4D/LR ROT long-range rotating radar. Hensoldt and IAI/ELTA have partnered to provide the air and surface surveillance radars, which are also suitable for the maritime Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) mission.

At the lower end of the shipboard sensor spectrum are high-power, night-vision capable EO/IR systems (including mounted binoculars) for detecting speedboats, divers, UAVs and other close proximity objects. An integrated laser rangefinder can provide guidance to close-in defence weapon systems. In America, the Shipboard Panoramic Electro-Optic/Infrared (SPEIR) programme will introduce the next generation of visual sensors to the US Navy fleet. L3Harris was selected as lead contractor for the programme in April 2022, with entry into service expected to begin in 2027. As expressed by L3Harris, SPEIR will elevate EO/IR sensors “from a dedicated weapons support sensor to a full passive mission solution capability.” The sensors will be mounted on the superstructure of surface combatants ranging from frigates to aircraft carriers and could potentially also serve on larger USVs. The system will support missions including ASM defence, counter-unmanned aerial systems (CUAS), counter-fast attack craft, and anti-terrorism/force protection at sea and in port. The firm’s SPATIAL sensor system will form the basis for SPEIR. Multiple sensors will be mounted on each ship, providing both narrow-field and 360° field of view.

Credit: Royal Navy

Systems such as the US Navy’s Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC) facilitate the use of shipboard weapons to achieve their full capability. CEC permits aircraft and ships to share sensor data and hand off targets to the unit best positioned for intercept, even if it does not have the target on its own radar. The European Union is currently developing the basis for an equivalent system under the EU Naval Collaborative Surveillance Operational Standard (E-NACSOS) project. This project aims to develop protocols, interfaces and targeting architecture to collaboratively identify, classify, track and defend against new and asymmetric air and missile threats. Naval Group is leading a consortium of 20 firms from 12 nations tasked with delivering the new capability. Prototyping and testing are expected to conclude by late 2027.

Defensive weapon systems

Defensive weapons options include interceptor missiles, deck-mounted projectile weapons, embarked helicopters, and – as a future addition to the arsenal – directed energy weapons. These weapon categories are constantly being upgraded and expanded.

Credit: EU

Interceptor missiles: While interceptor missiles are currently being used against UAVs, they are primarily designed to engage sophisticated, high speed, manoeuvring threats (aircraft, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles) at some distance from the ship. The Standard Missile (SM) family developed by Raytheon Missile Systems is a prime example of this weapon type. The SM-2 (RIM-66/67) is optimised for medium-range fleet area air defence and ship self-defence, but also has an extended area air defence projection capability. Depending on variant, the SM-2 has an operational range between 90 and 200 nautical miles. The latest variant, the SM-2 Block IIIC (RIM-67D), was approved for Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) in 2023. It features a dual-mode (active/semi-active) radar seeker for enhanced target discrimination and interception performance, especially against advanced, highly manoeuvrable threats. The extended range of the Block IIIC variants will also provide ships with a greater intercept envelope, especially when faced with saturation attacks. In 2027 the Navy hopes to field the Block IIICU upgrade. This will have similar performance to the IIIC but will be equipped with a new Guidance Section Electronics Unit (GS EU) to address pending obsolescence issues.

The SM-6 (RIM-174) missiles, also conceived to counter ASMs and combat aircraft, can additionally perform terminal stage intercept of short and medium range ballistic missiles. With a service ceiling of 33,000 metres, a speed of Mach 3.5, and an official range of 130 nautical miles, they can therefore defeat incoming threats ranging from those at very high altitudes to sea-skimming cruise missiles. The SM-6 Block IB variant will feature a significantly greater range than earlier variants and is expected to achieve Mach 5 or greater speed. With deliveries slated to begin in 2027, the enhanced variant will improve the US Navy’s capability to counter enemy hypersonic ASMs.

Several high-performance European and Asian interceptor missiles are also in development or in the early stages of operational use. One example is MBDA’s Sea Ceptor, the naval variant of the Common Anti-Air Modular Missile (CAMM). It was originally developed for use aboard British Royal Navy frigates but can be deployed on vessels as small as offshore patrol vessels. In service with the Royal Navy since 2018, Sea Ceptor is compatible with various vertical launch systems and is being expanded with extended range (ER) and medium range (MR) variants for service with various fleets.

Credit: Northrop Grumman

Guns: One major drawback of missile interceptors is their high cost. Pitting missiles costing several hundred thousand dollars or more against drones costing only thousands is not viable in the long term. Accordingly, guns firing airburst munitions with proximity fuses have recently found new applications in the force protection role against attack drones and small surface threats, both manned and unmanned. Leonardo’s OTO Melara 76/62 Super Rapid gun variant has a maximum firing rate of 120 rounds per minute and an effective range of 16,000 metres when firing High Explosive – Pre-Formed Fragment ammunition; The firm’s new Vulcano 76 munitions extend the gun’s range to 40,000 metres, and can utilise optional proximity fuses to combat incoming aerial or surface targets. Smaller calibre weapons such as 57mm guns are also effective against UAVs and manned or unmanned boats. For example, Northrop Grumman is developing a new 57mm high explosive guided munition for the US Navy’s Mk 110 gun mount. It is designed to defend against fast moving surface craft, drones and swarming threats. According to the firm, the new projectile has an on-board seeker to acquire moving targets and can manoeuvre in flight to achieve an intercept course. The fuse can autonomously select either proximity or point-detonation mode to maximise its kill probability.

Credit: AtlasElektronik

Railguns: The US Navy pursued an electromagnetic railgun capability for 15 years before suspending the programme in 2021 in favour of hypersonic missile research. In the meantime, both Europe and Japan have intensified their pursuit of the technology, which holds out the promise of the low-cost, high-speed interception of manned and unmanned aircraft, missiles, and fast surface vessels. The European Union’s TecHnology for ElectroMagnetic Artillery (THEMA) project aims to mature critical system components, including the pulsed power supply, the electromagnetic railgun itself, and s hypervelocity projectile. The EU envisages the weapon as a hypersonic interceptor with enhanced precision and lethality, complementing other defensive weapons such as missiles and guns. Tokyo is seemingly considerably further along. In October 2023 Japan became the first nation to fire a railgun prototype from a maritime platform. The weapon fires 40mm steel projectiles weighing 320 grams and has a muzzle velocity of Mach 6.5. The prototype uses five megajoules of charge energy. The Japanese MoD hopes to increase this to 20 MJ for an operational system with greater range and muzzle velocity. The weapon is designed to intercept aerial targets, with an emphasis on hypersonic cruise missiles.

Manned Aircraft: Embarked helicopters remain a solid option for defeating approaching air and surface threats at close to intermediate distance from a vessel. Naval helicopter armaments can include crew-served machine guns, air-to-surface missiles, and anti-submarine torpedoes. Defensive ASW – including detection and direct attack operations – is an established mission for shipboard rotary aircraft. During the ongoing operations in the Red Sea, coalition helicopters have repeatedly destroyed both explosive-laden USVs and aerial attack drones with their crew-served weapons.

Directed Energy Weapons: Electronic warfare (EW) capabilities have proven partially effective against unmanned systems – especially UAVs – in the Russo-Ukrainian war and are likely to prove a major defensive option against maritime drone swarm attacks as well. Tools such as frequency hopping and redundant navigation and targeting systems for unmanned systems will, however, limit the effectiveness of EW as a standalone weapon against drones, as well as against precision guided ordnance. Alternative types of energy weapons are therefore being tested for their suitability in these roles. Major advantages attributed to directed energy (DE) weapons include ‘deep magazines’ (unlike projectile weapons, DE systems can hypothetically fire as long as their energy supply is assured) and a favourable cost exchange ratio (a two-second burst from a 20mm Phalanx CIWS costs approximately USD 7,000, compared to an estimated USD 1 to USD 10 per laser shot).

The US Navy has been experimenting with high energy lasers (HEL) on ships since 2014, with each subsequent prototype exhibiting improved capabilities against UAVs and boats, including fast inshore attack craft. The US Navy Laser Family of Systems (NLFoS) currently consists of: the Solid State Laser Technology Maturation (SSL-TM) effort; the Optical Dazzling Interdictor, Navy (ODIN); and the High-Energy Laser with Integrated Optical dazzler and Surveillance (HELIOS).

The 150 kW Mk 2 Mod 0 laser weapon system demonstrator, which emerged from the SSL-TM program, began evaluation aboard USS Portland (LPD-27) in 2019. It defeated its first UAV in 2020. Meanwhile, eight Arleigh Burke class destroyers are using the ODIN to counter surveillance sensors in hostile UAVs. HELIOS is the most recent system and was installed aboard USS Preble (DDG-88) for testing in 2022. Initially delivered as a 60 kW class prototype, the US Navy hopes to increase its power potential to 150 kW. In the future, the navy hopes to deploy 300+ kW SSLs capable of countering anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM). In this respect, the High Energy Laser Counter-ASCM Program (HELCAP) programme will be tested in 2025 on land against air launched cruise missile surrogates. There will be no sea-based prototype of HELCAP; rather, the technology will flow into follow-up increments of HELIOS.

To date, maritime HEL applications range from blinding hostile sensors to downing drones or setting boats on fire. In January 2024 scientists with the Chinese Academy of Aerospace Aerodynamics published a paper discussing laser’s potential for combatting hypersonic missiles. In wind tunnel experiments simulating Mach 6 flight, the team used a HEL to ablate the missile’s protective coating, thereby changing airflow and destabilising the missile’s flight. Whether such an application would be practical for maritime defence remains to be seen. A major question is whether a laser could bring down a hypersonic weapon at sufficient range to prevent impact on the ship.

Overall, optimism regarding laser’s potential is increasingly muted. In contrast to initial hopes for long or medium range missile defence applications, the US Navy is now considering HELs a short-range weapon to engage threats with one (or at most a few) miles from a vessel. Concerns remain regarding lasers’ effective range, their beam cohesion in maritime environments, their energy requirements and the ability to defeat individual targets quickly enough to deal with swarm attacks. Additionally, some theorise that adversaries could shield their ASCMs from laser effects through reflective coatings. There is currently no visible timeline for transitioning developmental programmes to mainstream acquisitions.

High Power Microwave (HPM) weapons have performed well during land-based testing and are also being considered for shipboard applications. They can be directed against a broader area, so that a single microwave pulse could simultaneously disable the electronics on dozens of aerial or surface targets (including ASCMs and anti-ship ballistic missiles), making them more suitable than lasers for defeating swarm attacks. In January 2024 Raytheon was awarded a contract to develop and test two HPM prototypes; one each for the US Navy and Air Force. The navy prototype is to be delivered during 2024 and integrated into the land-based High Power Microwave Test Bed in 2025; following successful sub-component testing, the Navy plans to mount the prototype onto a ship for testing as early as 2026. Here, too, however, there is no established timeline for fielding an operational system with the fleet.

Credit: HII

Anti-Torpedo Torpedoes: Torpedoes launched from stealthy hunter-killer submarines remain a major threat to surface ships, as well as to other submarines. Modern torpedoes’ increasingly sophisticated seekers and guidance systems are diminishing the effectiveness of current decoy technology meant to divert torpedoes from their target. Consequently, anti-torpedo torpedo (ATT) concepts are attracting increasing interest. For example, AtlasElektronik presented its ‘SeaSpider’ solution at Euronaval 2022. The ATT is suitable for smaller vessels such as OPVs and Corvettes, as well as for larger warships. It is designed for all-up-round carriage in fixed launchers. The ATT launches within seconds of incoming torpedo detection. Equipped with a solid-propellant rocket motor, the agile, high-speed SeaSpider actively hunts torpedoes utilising a high frequency multi-mode sonar effective in both shallow and deep waters, destroying them by direct impact at relatively close proximity to the ship. Multiple ATTs can be launched simultaneously to combat swarm attacks. The firm aims to begin manufacturing in 2025; initial production would be configured for surface vessels, with a submarine variant to follow.

Unmanned Defensive Systems

Unmanned surface and underwater vessels are emerging not only as a threat to ships, but also as a defensive resource. US Navy budget documents underscore their utility as force multipliers in face of numerically superior enemies: “Large numbers of small, low signature, attritable unmanned missile launching vessels have the potential to improve surface force magazine depth and reduce risk to force in denied areas.” Being highly manoeuvrable, they are also well suited to counter asymmetric threats such as swarm boat attacks. Small enough to be carried aboard most warship classes, they can be deployed as advance scouts or as ‘guard dogs’ capable of intercepting threats within a 360° radius of the ship or task force. USVs can achieve speeds of 80 knots, and be armed with a variety of weapons including surface to air interceptors, surface-to-surface ordnance such as the AGM-114 Hellfire or Spike missile, machine guns and light autocannon, or light ASW torpedoes. Some USVs can also serve as motherships for UAVs and UUVs, further extending the manned ship’s effective sensor range.

The navies and industry of the United States, Europe, and Israel have all pioneered in this field. As just one example, the US Navy’s 2024 budget proposal included funding for the Multi-domain Area Denial from Small-USV (MADS) programme. The proposed platform for MADS is the MAPCorp Greenough Advanced Rescue Craft (GARC). This has a 400 nautical mile operating radius and has already been equipped with the remote-controlled Kongsberg Mk50 Sea Protector (which mounts EO/IR cameras, a laser rangefinder, and a selection of weapons), the GAU-19 rotary barrel machine gun, or AGM-176 Griffin or AGM-114 Hellfire missiles. The MADS proposal would equip the boat with FIM-92 Stinger missile launchers to “provide a low-cost, persistent anti-air and anti-surface maritime defense capability,” according to budget documents. The currently conceived primary mission would be armed escort for logistics ships. MADs could also potentially provide seaside security for amphibious forces in littoral zones.

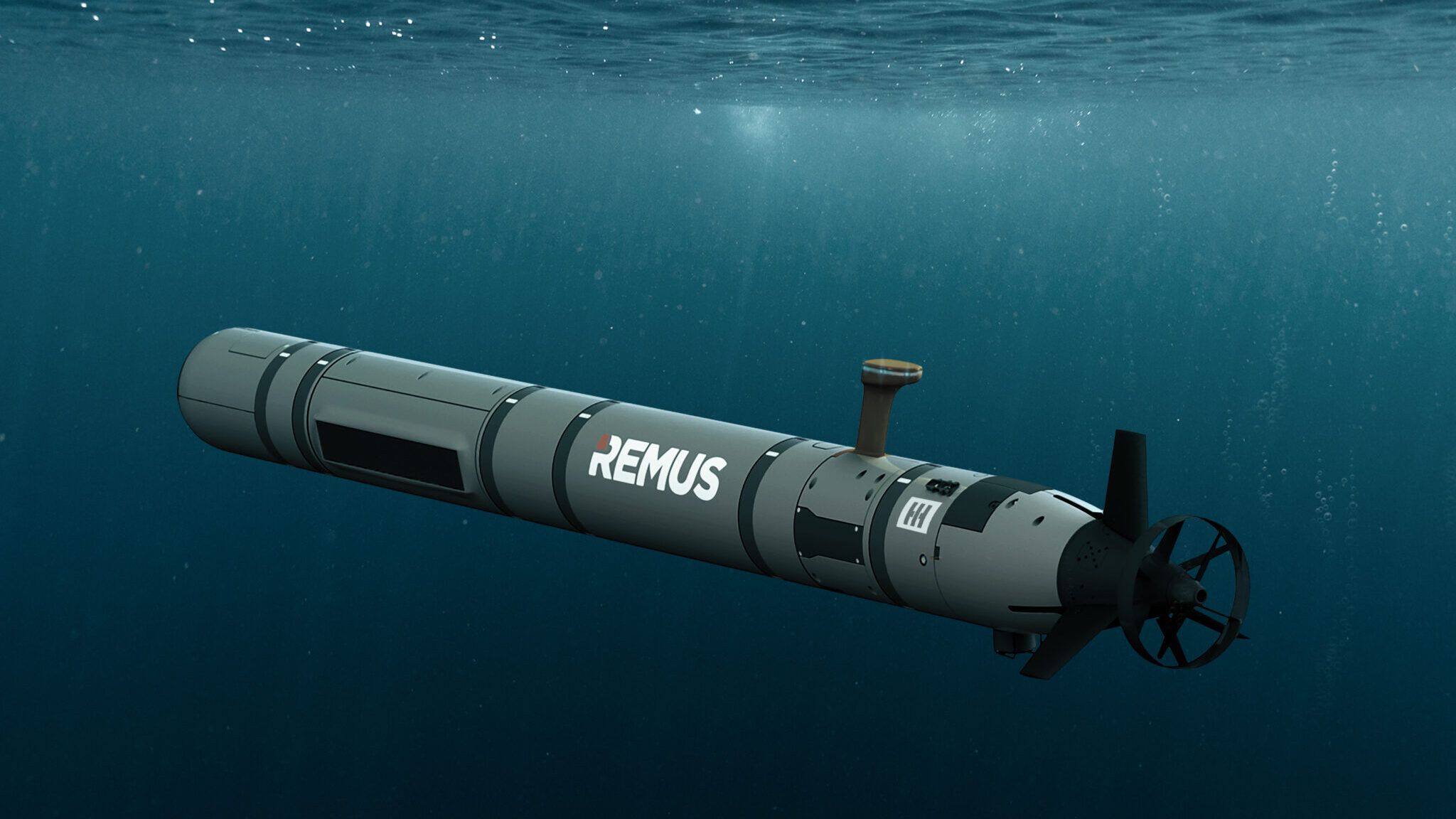

UUVs come in a wide range of sizes, from small to extra-large. Their mission potential is equally broad. Small and medium systems can be deployed from surface ships. Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Remus 620 medium-class UUV is a case in point. First presented publicly in 2022, the multi-mission UUV can perform EW, cyber operations, ISR, hydrographic surveys, and MCM, delivering effects both above and below the waterline. It can also carry and deploy smaller unmanned vehicles and payloads from underwater. Its 110 hour battery life and 275 nautical mile range permit the vessel to scout ahead or screen manned ships from surface or subsurface threats including attack submarines. Multiple units can be deployed by a submarine, boat or warship, and operate collaboratively.

UUVs’ potential is arguably best utilised in coordination with USVs, as well as with manned vessels. The SWarming And Teaming Shoal (SWAT-SHOAL) program is one of six naval projects selected in 2023 for development under the EU’s 2022 European Defence Fund. The EU’s stated goal is a system-of-systems concept to integrate various types of manned and unmanned naval assets collaborating as a team across a broad spectrum of underwater missions (including collaborative engagement) against moving subsurface threats. The focus is placed on technologies to enable innovative capabilities such as swarming, underwater communications, and autonomous operation to enhance naval forces’ versatility and capabilities in the underwater domain. Navantia is acting as project coordinator.

Leveraging AI to Enhance Fleet Defence

The latest US Navy/Marine Corps/Coast Guard Tri-Service Maritime Strategy was released in December 2020. The document finds that “new and converging technologies will have profound impacts on the security environment. Artificial intelligence, autonomy, additive manufacturing, quantum computing, and new communications and energy technologies could each, individually, generate enormous disruptive change. In combination, the effects of these technologies, and others, will be multiplicative and unpredictable. Militaries that effectively integrate them will undoubtedly gain significant warfighting advantages.”

Perhaps no single element will be more momentous than AI. Offensive weapon systems are increasingly being equipped with highly sophisticated AI supported guidance, targeting and control systems. While western nations continue to stress the ‘man-in-the-loop’ requirement before lethal force is applied, some adversaries are less concerned with collateral damage or rules of engagement; countering machine-controlled offensive systems will require defensive systems with comparable or superior capabilities. Viewing only the defensive aspect, it will be artificial intelligence which enables combat systems to process the vast amount of sensor data flowing in from dispersed platforms and collate the information into a usable form. Advances in AI will enable true autonomous operations by unmanned platforms and permit these platforms to coordinate operations with one another. Intercept of ultra-high-speed missiles will require computers capable of micro-second decision-making to prioritise targets and calculate vectors. The list goes on. While the horror-scenario of purely machine-driven warfare is not imminent, no single party can afford to fall behind in the AI race and hope to prevail.

Sidney E. Dean