Navies need connectivity to enable communications (including data transfer) between maritime uncrewed systems (including uncrewed underwater vehicles). Such a communications structure itself needs capability and design standards to enable it to work.

Maritime uncrewed systems (MUS) are being developed and procured as assets intended to assist NATO navies in adding capability and capacity in the current naval operating environment, including towards the higher end of the operational spectrum. In capability terms at this end of the spectrum, MUS can offer sensing, they can offer strike, and a range of outputs in between. In capacity terms at this end of the spectrum, they can offer mass. Even with this mass, though, a navy’s human operators and its uncrewed systems need communications with each other and with others to generate effect. Whatever capability or capacity a navy has, its effect will be limited if systems (crewed or uncrewed), operators, and operations are not connected. In other words, connectivity ‘talks’.

The challenge for naval operators is that different navies operate different platforms, weapons, and systems, equipment that is largely designed and built differently because it is developed for different – and national – customer requirements by different – and often national – industry suppliers. While there is habitually significant overlap between such equipment in capability and output terms, the connectivity that should enable them to operate and integrate effectively can be different enough to the point that such effect connectivity, integration, and operation is a challenge.

In other words, there is a need for standardisation in connectivity to enable platforms, weapons, systems, and even people to ‘talk’.

This is not a challenge that is new with the arrival and use of MUS. Capability design standards are something NATO has been developing for some time. The alliance has a long-standing process of developing what are known as standardisation agreements, or STANAGs. In terms of communications STANAGs, key examples demonstrate the importance of communications connectivity and the role of a STANAG in enabling this.

“A STANAG is a NATO document that specifies the agreement of member countries to implement a standard,” according to NATO. These standards encompass “rules or guidelines that ensure mutual understanding and practical functionality”, it added.

Specifically, NATO defines a standard as a document, established by consensus and approved by a recognised body, that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines, or characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context. Within such a document, the standard may define the development and implementation of concepts, doctrines, and procedures to achieve and maintain the required levels of compatibility, interchangeability, or commonality needed to achieve interoperability.

Credit: US Navy

“Standards enable people from a wide variety of countries and backgrounds to have compatible equipment, to understand each other’s methods and procedures, and to operate smoothly even if they have just started working together,” according to NATO. “This is … interoperability, which is the ultimate goal of standardization.”

The alliance’s STANAG development is led by the NATO Standardization Office (NSO), “which initiates, co-ordinates, supports, and administers NATO standardization activities”, NATO stated. As part of this process, the NSO – which, since 2014, has been an integrated NATO Headquarters staff element, reporting to NATO’s Military Committee and the Committee on Standardization – works with the Military Committee on developing the broad concept of and process for developing military operational standards.

This fits within NATO’s broader Defence Planning Process, which is the alliance’s primary means for identifying required capabilities and promoting their timely, coherent development and acquisition by allies; within this context, the NSO encourages STANAG implementation through defence planning. Overall, according to NATO, “These activities foster NATO standardization with the goal of enhancing the interoperability and operational effectiveness of alliance military forces.”

Currently, more than 1,200 STANAGs are promulgated within NATO. STANAGs cover the full range of military capabilities, including ammunition sizes, air-to-air re-fuelling capability, rail gauges, common markings on ships or aircraft supporting the same operation, formats for information sharing, procedures for moving logistics, the words that troops use to communicate with each other, and compatibility in communications equipment.

In certain capability areas – particularly communications technology – the STANAGs are complex, relating to the technological design, capability, and integration of a communications system.

Linking capability

One of the most important NATO STANAGs developed and implemented to date is the process that underpinned the alliance-wide introduction of the Link tactical data system. The three most prominent Link networks NATO has established are Link 11, Link 16, and Link 22.

The Link tactical communications network enables data exchange across a secure radio system that connects air, surface, sub-surface, and ground-based data systems. Link 22 is the latest iteration, and is designed to replace and upgrade the capability provided in Link 11 and Link 16.

In tactical operations-level terms, the Link network is a standardized communications system designed to transmit and exchange real-time tactical information between network participants.

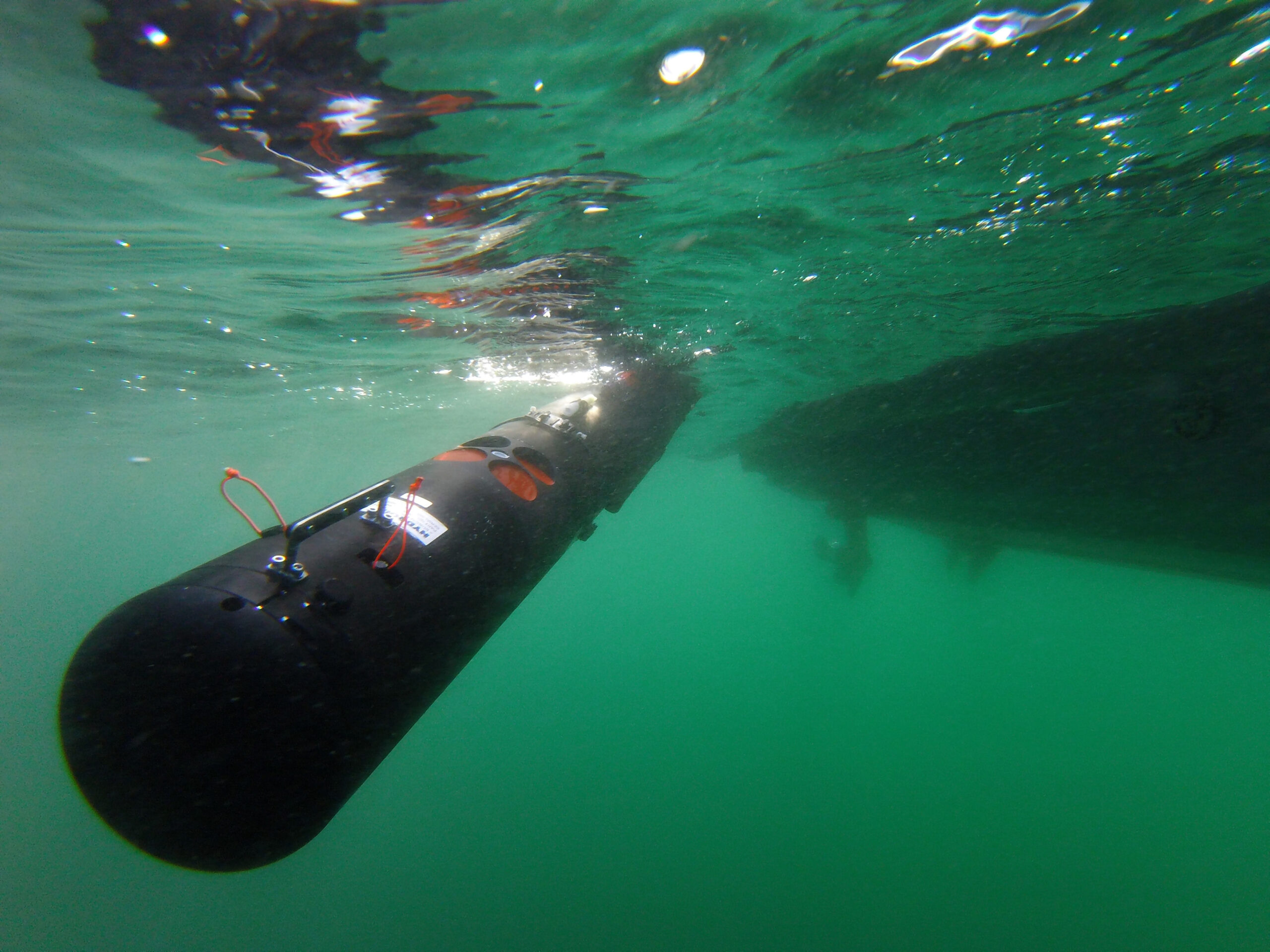

While the Link network is a multi-domain structure, what is new today is the need to integrate MUS, and especially uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs) – the latter operating, of course, in the underwater domain, which still presents basic, physical communications challenges from a technology perspective. To meet this new communications requirement, a bespoke STANAG is being developed – what is arguably one of NATO’s most critical current and recent STANAGs.

STANAG 4817 is being designed to provide seamless, multi-domain command and control (C2) of MUS. Such C2 is the critical enabler for MUS operations, particularly in the underwater domain. Here, this C2 will enable the transportation and sharing of increasingly important data and the information that is processed from it.

Credit: NATO

Operational context

Such information harvested from the underwater domain includes habitual task areas such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and indicators and warnings (INW), which remain integral to building wider maritime domain awareness (MDA).

In the modern naval operational environment, some traditional underwater sensing tasks – for which UUVs are ideally suited, with the information they glean and the actions they take being operationally crucial – are increasingly important. While connecting uncrewed systems for mine counter-measures (MCM) operations is an established concept, and represented the first regular use of UUVs in order to remove crewed platforms from harm’s way, MCM operations are today an area of greater focus for underwater C2 of MUS capability due to the wider use of mining for operational effect, for example to close off access points. This is being demonstrated in the Russo-Ukraine war, with both sides mining littoral waters in the Black Sea. The new mine threat that has emerged in the war – that of drifting mines, which are flowing freely across the Black Sea – underlines the blue-water MCM threat, too. In the absence of a naval force structure, following its fleet largely being destroyed during not only the current conflict but also during Russia’s invasion and subsequent annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine is using UUVs to conduct MCM operations.

For anti-submarine warfare (ASW), increasing Russian activity and capability across wide areas of the Euro-Atlantic theatre’s underwater domain is creating the challenge for NATO of geography and mass. The alliance’s relatively limited collective submarine capacity (relatively limited, in terms of boat numbers compared to areas and tasks to cover) means there is an increasing focus amongst NATO navies on developing MUS capabilities – and especially UUVs – to provide the more routine presence and sensing capability. Sustained, and sometimes forward-deployed, sensing capability is something NATO navies have often done with submarines. However, what is new today is the use of UUV capabilities to provide this routine sensing presence, especially through the establishment of ASW barriers.

What is also new in the underwater domain in terms of building connected capability is the use of MUS across all domains to deter and defend against the growing threat to critical undersea infrastructure (CUI) situated on the seabed. Recent years have seen several high-profile incidents occur, most notably the Nordstream gas pipeline explosions and the BalticConnector pipeline and cable ruptures (both incidents occurring in the Baltic Sea, in September 2022 and October 2023 respectively). The importance of deterring and defending against CUI threats is significant enough for NATO at national and alliance levels that member states are investing in bespoke equipment and are testing its connectivity at one of NATO’s most prominent exercises – the Portuguese Navy/NATO Maritime Command (MARCOM)-hosted ‘REPMUS’/‘Dynamic Messenger’ combined MUS exercise, which takes place off Troia, southern Portugal in September each year.

At the 2023 iteration of the exercise, uncrewed air vehicles (UAVs), uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), and UUVs were employed in integrated layers to locate a seabed cable, secure it, and deter and defend against a direct threat to it.

Barriers to progress

Concepts for building barriers consisting of integrated, connected UUVs (either autonomous underwater vehicles or underwater gliders) to secure CUI or to provide ASW barriers across maritime choke points are designed to provide potential obstacles to the operational progress of adversary submarines, which might be seeking to threaten such CUI or slip through such choke points.

Credit: US Navy

NATO’s Smart Defence Initiative ASW Barrier is a key concept the alliance is developing to build capacity to establish sensing networks in key places at key times, for example around CUI sites or at choke points. The concept is based around delivering integrated, connected webs of UUVs, plus other crewed and uncrewed platforms. One potential obstacle to capability development progress here that NATO is tackling, in the process of delivering this capability, is establishing the standards required to enable the build and operation of this network, plus several other MUS communications architectures that enable and support this and other MUS operational constructs.

STANAG 4817 was conceived to determine the MUS connectivity and communications architecture design standards required to enable the establishment of an integrated MUS network, including its operational C2. Such networks are the glue that binds the operational capability and effect together.

“You cannot have a UUV if you cannot operate it,” Rear Admiral James Parkin – the UK Royal Navy’s (RN’s) Director Develop – told the Undersea Defence Technology (UDT) exposition, held at London’s ExCel exhibition centre in early April.

Operators need to be able to offboard the data from the UUV, he continued. This is done using connectivity networks. Alongside offboarding data, such networks need to provide the required MUS C2, and must be underpinned by a resilient, secure, and seamless infrastructure.

The RN’s StrikeNet communications architecture – the navy’s digital backbone for supporting dispersed operations and distributed C2, and which evolved from its MAPLE NSN (Maritime Autonomous Platform Exploitation naval strike network) construct – is an overarching C2 framework under which STANAG 4817 has been developed. Rear Adm Parkin told the UDT conference that STANAG 4817 sits at the heart of the StrikeNet construct, and steps allied interoperability forward into interchangeability.

“We will buy nothing or use nothing unless it is compatible,” said Rear Adm Parkin. “STANAG 4817 is how we will win the next war.”

REPMUS development

The ‘REPMUS’/‘Dynamic Messenger’ exercise construct is a driving force for development in terms of building MUS capability and the requisite STANAGs, and integrating and testing them including in operational experimentation using active NATO task groups. The effectiveness of integrating MUS systems with each other and into operations, along with the underpinning C2 infrastructure and architecture, is already being demonstrated in the ‘REPMUS’ outputs.

Credit: Portuguese Navy

For example, in an MCM serial conducted at ‘REPMUS 2023’, a US UUV autonomously located a mine contact and tasked two other UUVs (one British, and one Dutch) to investigate the contact and complete the rest of the mine clearance task, a senior NATO official told a media briefing at the exercise. “The UUV level of autonomy has increased probably two- or three-fold this year,” the official said, adding that the collaborative autonomy demonstrated in the MCM serial was achieved with no human intervention.

“The UUVs were assuring the commander that the area of sea was clear of mines,” the official continued. “To put it into metrics, if you were to use a single national system to clear the same seaspace, it would have taken about 18 hours. With three systems from three different countries working collaboratively, it took two-and-a-half hours.”

In terms of delivering usable capability, this example underlined the importance of collaborative autonomy as a principal, but also the impact of a common C2 architecture, as being defined and developed under STANAG 4817.

Mines present a covert sea denial challenge to NATO navies operating in a particular seaspace, particularly as any reported mine contact will require investigation. Thus, the ability to work collaboratively to clear an area more rapidly offers distinct operational advantage.

The drifting mine challenge was also used in serials at ‘REPMUS 23’. The ‘REPMUS’ environment provides a particularly useful construct within which to develop and test a STANAG like 4817. STANAG 4817 is the standard that NATO will be using to develop the capacity required to tackle the threats that MUS capability is applicable to. The exercise brings the operational experimentation and military operator communities together with the scientific operational research community – with key research stakeholders like the NATO Science and Technology Organization’s La Spezia, Italy-based Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) playing a central role in planning and conducting the exercise. This enables the two communities to combine the expertise they bring and the data they generate in order to develop an operational construct such as STANAG 4817. Combining the range of expertise and data developed across the exercise’s operational experimentation, and then feeding lessons learned into NATO operational tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), was a central aim of STANAG 4817’s ongoing development process in ‘REPMUS 23’.

In this context, STANAG 4817 is a key step in developing the alliance’s capability to use MUS to deliver a common operational picture. Simply put, STANAG 4817 will pre-define what NATO needs in terms of compatibility from MUS systems developed to support NATO exercises and operations, with a particular emphasis on being able to contribute to the development and sharing of that picture. STANAG 4817’s role in how NATO maritime systems, including MUS, develop and distribute data is crucial.

Credit: NATO

“We are in an operating environment where we are using data like never before. We’re going in the direction of data-centric warfare,” Commander Antonio Mourinha – a Portuguese Navy officer posted as Director of the navy’s Troia-based centre for operational experimentation (CEOM), and ‘deployed’ on ‘REPMUS’ as Chief of Staff – told the exercise media briefing. “The use of MUS and their payloads, and the ability to connect all of them together and to use this data extensively is key to the success of operations. This is real here [in ‘REPMUS’], is real in Ukraine, and is real in any place.”

“An uncrewed system doesn’t have value unless it can carry something that is useful,” said Cdr Mourinha. Such things of use that add value, he explained, are payloads that provide a sensor, an effector, or data-gathering/data-using capacity in some way. “It is really important that we have the ability to assess, [in the location] where we are, the data that is being collected by the MUS. This is what is useful for the commander in the operation.”

For ‘REPMUS 23’, testing and experimentation with MUS (especially UUVs) using multi-domain C2, integrated through STANAG 4817, was one of the major objectives, said Cdr Mourinha. “This is going to become a NATO standard, under STANAG 4817,” he continued. “STANAG 4817 is going to be a NATO standard for high-level, multi-domain C2 of unmanned systems. This will allow you to have a system that communicates with other systems, and that can give orders to other systems. It is a ‘system of systems’.”

In sum, the use of STANAG 4817 to build a ‘system of systems’ is intended to allow data to flow between assets and C2 nodes to build the common operational picture. “We are really shaping the future of these data flows,” said Cdr Mourinha. “We look to use not only MUS but [other] systems to collect data, to fuse data, and to process data, and to provide the operators with the best advice in terms of how to proceed.”

While STANAG 4817 continues to develop, ‘REPMUS 23’ used two main C2 networks: the CMRE-developed Collaborative Autonomy Tasking Layer (CATL) protocol, which focuses on passing information – including commands – between different MUS; and the UK/US-developed I2I (Interoperability to Interchangeability) network, which focuses on connecting up different C2 nodes as well as different national networks (for example, the UK’s MAPLE NSN).

Credit: NATO

CATL and I2I send different messages using different ‘languages’. STANAG 4817 will provide a common set of technical and operational standards within a common C2 architecture standard in the longer term, including capacity to blend different communications ‘languages’, Cdr Mourinha explained. A standard is like using a common language, he added.

The importance of STANAG 4817 is such that NATO navies are continuing to prepare to send platforms and systems to ‘REPMUS 2024’ for C2 evaluation and integration. For example, at the SAE Media Group’s Maritime Reconnaissance and Surveillance Technology conference in London in January, the discussions noted that the Italian Navy is planning to send a frigate to the exercise in 2024 with a combat management system that is STANAG 4817-compliant.

Back at the ‘REPMUS 23’ media brief, Cdr Mourinha reinforced the simple importance of constructs like STANAG 4817 for NATO. “The war of the future will rely very much on connectivity,” he said.

Dr Lee Willett

![Hybrid navies: Integrating uncrewed capability into carrier strike The US Navy (USN) carrier USS John C Stennis (left), the French Navy carrier FS Charles de Gaulle, and elements of their strike groups are pictured sailing together in US Fifth Fleet’s area of operations. The US, French, and UK navies are all developing ‘hybrid’ crewed/uncrewed mixes for their carrier airwing capability. [US Navy]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/2-HST-CdG-USN-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Strategic shift: UK CSG deployment demonstrates switch in UK strategic focus The UK aircraft carrier HMS Prince of Wales (foreground) sails alongside the US carrier USS George Washington during Australia’s ‘Talisman Sabre’ exercise in July 2025. The two carrier strike groups (CSGs), plus Australian Navy assets, conducted CSG integration activities. [Crown copyright 2025]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/1-PWLS-GW-TSabre-CC-UK-MoD-25-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Ripples in the air, rupture in the ether Pictured: 1L269 Krasukha-2 jamming system. Since 2008, Russia has greatly expanded its EW capabilities, and since 2022 it has gained valuable direct experience contesting the EMS in Ukraine, where continuous innovation occurs over very short timescales. [RecoMonkey]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1L269-Krasukha-2_RecoMonkey-Kopie-218x150.jpg)