Supply pre-positioning: considerations for today’s European context

Manuela Tudosia

Security of supply and strategic stockpiling are topping today’s agenda in civilian and military settings. Less debated but no less important, is the strategic pre-positioning of war reserve materiel near the points of need.

According to DoDD 3110.07, Prepositioned War Reserve Materiel (PWRM) is “war reserve materiel and equipment strategically located to facilitate a timely response in support of Combatant Commander requirements during the initial phases of an operation”. Pre-positioning reduces the demand for strategic airlift and sealift assets, and it includes starter stock, materiel situated in or near a theatre of operations calculated to sustain actions until resupply at wartime rates are established, and swing stock, materiel ashore or afloat available for planning purposes to augment war reserve requirements.

Credit: NATO

Though the US Department of Defense (DoD) PWRM definition does not include defence equipment stockpiled for foreign countries, the definition itself can be used to illustrate the concept of supply pre-positioning more generally. In terms of coverage, this can vary according to estimated needs, and it can include materiel from the five NATO Supply Classes highlighted by Jean Auran in Combat Supply Operations (ESD, 8 March 2024).

In Europe today, discussion about supply pre-positioning can be sensitive and complex:

- In terms of public opinion, the topic can trigger assumptions of possible imminent war, creating concern and even panic among the population.

- Sovereignty-wise, a balance must be struck between strictly national matters and information sharing with Allies for common defensive goals.

- Operations-wise, supply pre-positioning can only be properly planned and implemented with input from combatant commanders, based on strategic guidance and reliable threat-related intelligence; therefore, possible operational scenarios must be anticipated and pre-positioning planned accordingly. However, public or adversarial knowledge of the location of supplies and/or any other related details can represent an operational vulnerability.

Due to the above limitations, many aspects that concern supply pre-positioning can be subject to security classification. However, several considerations can be made regarding factors that contribute to a resilient supply pre-positioning system in Europe today.

Supply pre-positioning is a normal and effective precautionary measure to enhance readiness. Today’s strategies must be adapted for multinational and distributed operations, and assume a contested logistics environment. Whether intended to respond to civil emergencies or to dissuade and counter geopolitical risks, supply pre-positioning has always been an integral part of preparedness strategies. What appears necessary today is to adapt pre-positioning strategies to cover a higher complexity of emerging threats and, possibly, a wider geographical territory.

Since the Cold War, Europe’s deterrence and defence posture was strengthened by the US’ pre-positioned stocks in Europe, notably the Army Pre-Positioned Stocks (APS), which have served both for military exercises such as Defender 2023, and as a response to war situations, including Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

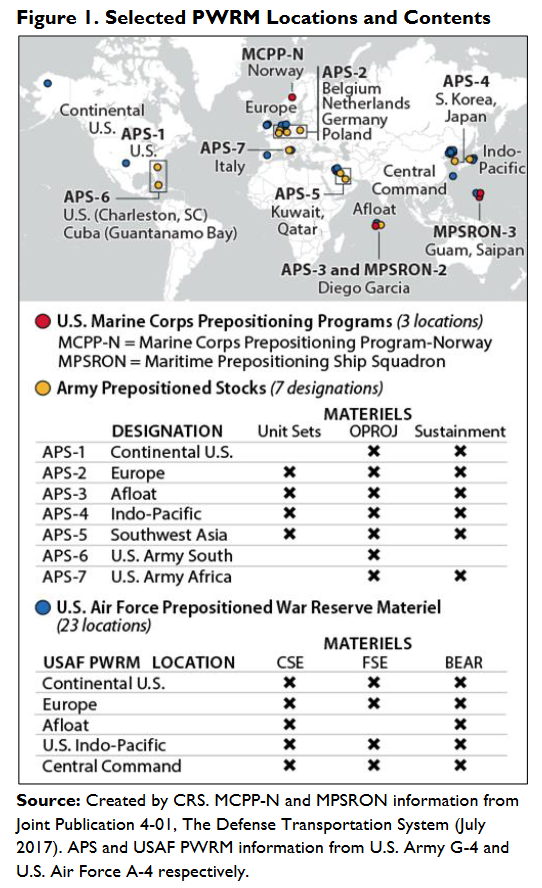

US pre-positioning strategies in Europe and globally have been constantly evolving with the changing nature of threats and expected type of operations. A more recent outlook of the US pre-positioning is offered by the US Congressional Research Service report Defense Primer: Department of Defense (DoD) Pre-Positioned Materiel, updated in August 2024. The report explains the rationale for pre-positioning of materiel at or near points of planned use (abroad) and summarises the US Army, Navy and Marine, and Air Force PWRM programmes.

Credit: Congressional Research Service

Lessons from the Ukraine war, but also the identification of threats such as China, have contributed to the assumption that future operations must be planned for challenged or contested logistics environments, characterised by reduced mobility, resource-constraints and disruptions to the supply chain. This assumption is enshrined in the 2023 US Army Joint Warfighting Publication (Volume 1): “In the future, joint forces will operate independently in degraded communication environments with mission-type orders and challenged or contested logistics.” This also implies that large pre-positioned stocks can quickly become vulnerable and that an adapted approach to pre-positioning is needed to respond to the necessities of large scale conflicts and to multi-domain operational concepts. The 2015 US Joint Chiefs of Staff ‘Joint Concept for Logistics’ document anticipated that pre-positioned stocks must be easy to move quickly between theatres and must be part of highly modularised logistics capabilities. The latter referred “to the ability of logistics elements at increasingly lower echelons to detach from their parent headquarters and combine effectively with similar elements from other Services or organizations to form flexible tactical groupings”. This implies the ability “to create logistics organizations of practically any size and composition”.

Similarly, in line with the concept of multi-domain operations (MDO), this adaptation of supply pre-positioning strategies appears to be highly relevant for the European and NATO contexts where multinational operations are more likely to happen than purely national ones. In the current European context, pre-positioned stocks may need to be smaller, greater in number, highly mobile and modular.

The NATO 2022 Strategic Concept had already stressed the importance of pre-positioned ammunition and equipment to strengthen the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture. The implementation of the new NATO Force Model decided upon at the June 2022 Madrid Summit is paired with the commitment to improve the Alliance’s ability to reinforce and sustain Allied forces across Alliance territory, including through greater logistics coordination and the pre-positioning of ammunition and equipment. It should be noted that while implementation might be coordinated at NATO level, the prepositioned stocks themselves are likely to be a national investment.

The US Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) budget request of USD 2.91 billion includes the request for enhanced pre-positioning of select equipment and materiel across all supply classes worth of USD 713.2 million. This line of effort aims to address “capability gaps and improve response timelines for responding to potential Russian attacks against NATO”.

Not much is known about the European NATO countries’ own pre-positioning plans or approach. Many play a key role in facilitating the US pre-positioning of equipment. For example, the bilateral Defence Cooperation Agreement (DCA) between Sweden and the US that entered into force in August 2024, enables cooperation by regulating the conditions for US forces to operate in Sweden, which involves pre-positioning of military materiel. In a similar vein, Germany, Poland, and others support and facilitate US supply pre-positioning.

Credit: NATO

It is assumed that the implementation of the new NATO Force Model and the associated Force Structure Requirement, which determines the equipment and units needed, will involve cooperation among the Allies on supply pre-positioning beyond the US presence in Europe alone. NATO’s Multinational Ammunition Warehousing Initiative (MAWI) is just one publicly available example of NATO nations’ commitment to invest in this direction. MAWI, which involves 23 NATO Allies, facilitates pre-positioning of munition stockpiles in support of NATO’s multinational battlegroups on the Alliance’s eastern flank.

Pre-positioning cannot replace long-term security of supply and a strong industrial base capable to sustain war effort

As mentioned above, supply pre-positioning mainly serves initial phases of operations, pending establishment of supply lines and surge of production. Without effective security of supply, manufacturing capacity and strategic stockpiling strategies, supply pre-positioning alone is not sufficient to sustain operations for long.

Determined efforts have been made over the past four years to mitigate and solve security of supply challenges, at national, European and NATO levels. Despite touching the core of national sovereignty, coordinated solutions have been sought in some of the most sensitive areas, including ammunition and critical raw materials. These efforts are likely to positively impact the sustainment of forces and supply pre-positioning strategies.

Security of supply and manufacturing capacity have been matters of serious concern for NATO, leading to several initiatives. Notably, at their June 2024 meeting, the NATO Defence Ministers endorsed a defence-critical supply chain security roadmap with five lines of effort:

- Identifying key strategic materials essential for allied capability development and delivery;

- Establishing a NATO community of interest on defence critical supply chain issues;

- Establishing a way to share assessments regarding supply chains;

- Identifying recommendations for strategic stockpiling;

- Identifying opportunities for recycling and substituting key strategic materials.

At the EU level, after implementing the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) and the European Defence Industry Reinforcement Through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) as short-term emergency measures, the European Commission proposed the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP), an EU Regulation meant to bridge the gap between these short-term measures and ensuring long-term defence industrial readiness. EDIP provides for the creation of an EU-Wide Security of Supply (SoS) Regime aimed to “support Member States’ efforts in pursuing the highest possible level of Security of Supply when it comes to defence equipment”. This includes measures to facilitate response to the current geopolitical context (for example, stock replenishment), to simplify re-opening of existing and future framework contracts with the defence industrial base, to identify and monitor critical products and industrial capacities in the supply chains of certain defence products, and to assure a modular and gradual crisis management framework, should a crisis arise.

Credit: NATO

The EU-wide SoS Regime is expected to facilitate priority access to certain products that are critical for the supply of defence products, and is considered a defence-oriented complement to the ‘Internal Market Emergency and Resilience Act’ (IMERA), which focused on the civilian SoS dimension. Learning from past lessons (notably, the COVID-19 pandemic, the War in Ukraine, and the energy supply crisis), IMERA creates mechanisms to anticipate, prepare for and respond to the impact of future crises. Although watered down during the legislative negotiation processes, both IMERA and the EU-Wide SoS Regime place targeted information requests obligations and manufacturing prioritisation requirements upon European economic operators, depending on the supply risks identified. In different stages of EU Ordinary Legislative Procedure, IMERA and EDIP are expected to be adopted later in 2024.

The measures taken by the EU, coupled with the adaptation of supply pre-positioning strategies to a contested logistics environment may anticipate several challenges and opportunities to be tackled by civilian and military leaders in the coming years.

Civil-military cooperation may increase in importance and scope

Information and prioritisation obligations imposed on certain economic operators, as proposed by the SoS regime, could open debates of an economic, societal and political nature. The legitimacy of such obligations will have to be explained and wide stakeholder support will have to be obtained through trust-building strategies. Without such support, implementation may be hindered by resistance and even disinformation campaigns fuelled by opposing forces. Moreover, cooperation with civil economic operators to strengthen security of supply may need to be complemented and expanded to cooperation with local leadership and communities for supply pre-positioning considerations. Well-thought through, coordinated, stakeholder outreach and communication strategies may be useful to secure wider adherence.

Product support strategies may need reconsideration alongside re-thinking of operational contract support frameworks

If a model of smaller, highly mobile and modular pre-positioned stocks of equipment is adopted, which would consider large-scale combat scenarios, current product support pace may need adaptation to match new conditions of size, storage, mobility and other requirements. Current contracted support to operations may also require adaptations and renegotiation with the suppliers. In addition, the entire concept of contracted support to operations may come under discussion for adaptation to large-combat scenarios. Whereas the demand for a skilled technical workforce for the maintenance and operation of complex weapon systems could become higher, the question is if armed forces will have sufficient personnel in-house, or whether additional support would have to be contracted. Regarding the latter option, difficult questions would need to be answered regarding safety of the civilian personnel should they need to be deployed to active combat areas, but also regarding the diversity of skillsets to cover an equally diverse set of systems originating from various NATO countries.

Credit: Bundeswehr/Jaap Boosman

Resilient military mobility and infrastructure are more important than ever

Military mobility is essential not only for supply pre-positioning but also for sustaining operations over longer time periods.

Steps to improve military mobility in Europe were taken by the EU and NATO even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and synergies between the two organisations are sought through the mechanism of Structured Dialogue on Military Mobility, established in 2018. Important coordination and harmonisation was achieved between the EU countries on cross-border movement permissions and customs regulations. The Network of Logistic Hubs in Europe and Support to Operations, a Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) project, will allow multinational use of existing logistics installations and depot space for spare parts or ammunition, and to harmonise transport and deployment activities. In addition, the PESCO ‘Military Mobility’ project supports simplification and standardisation of cross-border military transport procedures.

Beyond harmonisation and coordination efforts, a potential challenge that will have to be addressed is the discrepancy of mobility and logistics infrastructure between certain European member states, especially on the Eastern flank. This is likely to require adaptation of pre-positioning strategies to match terrain, infrastructure and even economic realities of each country. In addition, the practical impact of climate change, as witnessed by increased extreme weather events over the last few years should not be underestimated.

Closing thoughts

The planning of military supply pre-positioning in Europe is likely to continue being driven by a large scale conflict scenario, where the most obvious adversary would be Russia. However, whereas coordination in NATO and EU multinational settings can facilitate the planning and deployment of pre-positioned supplies, adaptation to national and local realities could be a decisive factor for success. In addition, supply pre-positioning cannot be decoupled from longer-term sustainment of operations, which requires solid security of supply strategies and surge manufacturing capacity. The latter are challenges that are gradually starting to be addressed.

Manuela Tudosia