Europe remains a focal point of submarine construction and technological innovation. The industry placed heavy reliance on securing export orders to sustain their operations during the difficult, post-Cold War years, albeit some rationalisation was inevitable. With a changed political background, many manufacturers are now scrambling to find ways to meet an upsurge in domestic demand as navies seek to rebuild their underwater capabilities. This article looks at the fortunes of the region’s current major players.

France: Naval Group

France’s Naval Group is arguably Europe’s leading submarine manufacturer, being the only European company to have recent experience of manufacturing both nuclear-powered and diesel-electric designs. The focal point of its submarine business is its shipyard at Cherbourg in Normandy, where all French-built submarines are currently constructed. The facility is dominated by the huge, 190 metre long ‘Labeuf Hall’, which is used for final assembly. Naval Group’s submarine activities are supported by an extensive national ecosystem of sub-contractors, amongst the most significant of which are MBDA (weapons), Safran (optronics), Thales (sonar and communications) and TechnicAtome (reactors). Naval Group’s ongoing involvement in the production of advanced anti-submarine warships such as the Franco-Italian FREMMs also arguably gives it an advantage in understanding the opponents its submarines will need to combat

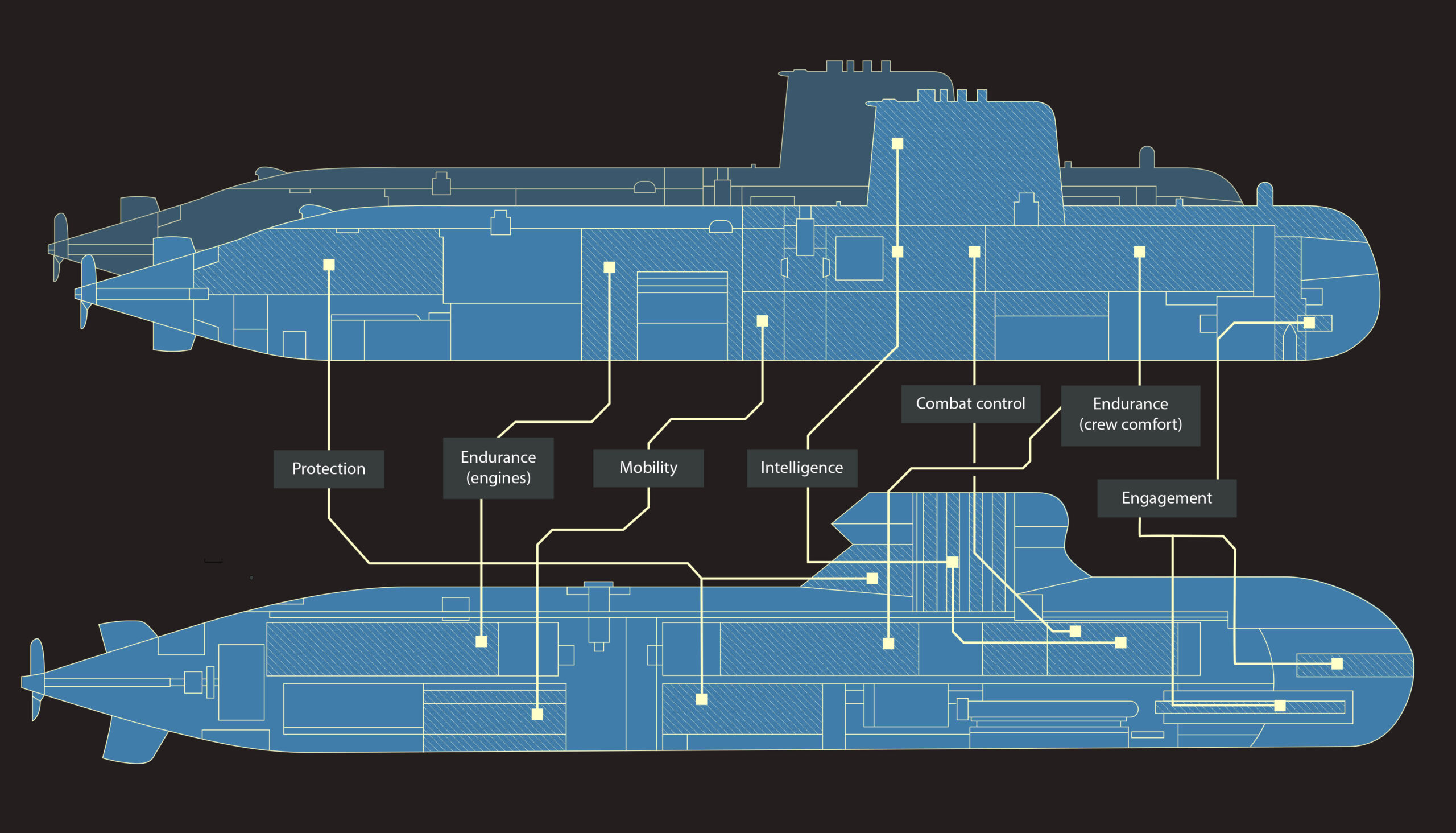

Credit: Naval Group

Naval Group’s submarine activities have two distinct, if closely intertwined elements. One of these is construction of nuclear-powered submarines for the French Navy. The most significant project of recent years has been the ‘Barracuda’ programme to build a replacement for the Cold War-era Rubis class. This has given rise to the construction of six nuclear-powered attack submarines of the Suffren class under a series of contracts that were placed from December 2006 onwards. The lead boat was delivered in November 2020 and was followed by her sister FS Duguay-Trouin in July 2023. The third member of the class is currently in the course of sea trials whilst work is underway on all the remaining submarines in line with a programme schedule that envisages the final boat being delivered in 2030. The likely near 25 year-long span of construction activity gives a good indication of the size and complexity of the programmes that Naval Group is able to undertake.

The ‘Barracuda’ class are being followed into production by France’s third generation strategic submarine design, otherwise known as the SNLE-3G. Formally launched in 2021, the SNLE-3G programme envisages the numerical like-for-like replacement of France’s existing four Le Triomphant class boats over the two decades from around 2035 onwards. A first steel-cutting ceremony for the lead unit was held at Cherbourg in March 2024, marking the start of the production phase. The security and continuity in workload enjoyed by Cherbourg’s construction activities through France’s unwavering commitment to its underwater nuclear deterrent provide a firm foundation for Naval Group’s overall submarine business.

Although the French Navy made a conscious decision to phase out its non-nuclear powered submarines after the end of the Cold War, Naval Group has nevertheless managed to remain a leading player in the international market for these boats. A major element in this outcome was the early success achieved by its ‘Scorpène’ design, which was originally produced in collaboration with what is now Spain’s Navantia. The design gained many export contracts and currently remains under licensed production in Brazil and India. To some extent, however, this strong position was subsequently undermined by Naval Group’s failure to develop a commercially successful air independent propulsion (AIP) system, reducing its competitive strength in export markets. Another major blow was experienced in September 2021 when Australia cancelled its planned local construction of the group’s ‘Shortfin Barracuda’ design in favour of Anglo-American nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS security pact.

Credit: Navantia

Recent developments have been more favourable. Early 2024 saw the announcement of two major export awards that have put the group’s international business on a firmer footing. The first success came on 15 March 2024 when the Netherlands provisionally selected the diesel-electric ‘Blacksword’ variant of Naval Group’s ‘Barracuda’ family for its own replacement submarine programme, partly mitigating the impact of Australia’s earlier decision. Later that month, Naval Group also announced that two ‘Scorpène Evolved Full LiB’ submarines would be assembled by PT PAL in Indonesia under a transfer of technology arrangement. This latter award suggests that progress in lithium-ion battery technology has mitigated the group’s relative weakness in the AIP sphere. Given the already-strong domestic demand position, Naval Group’s major challenge now seems likely to be driven by the inevitable challenges created in managing the resultant increase in work.

Germany: tkMS

Germany’s thyssenkrupp Marine Systems (tkMS) is arguably Naval Group’s most significant rival amongst European submarine builders. Its submarine business’s current structure traces its origins to consolidation of much of the German naval sector under the ownership of thyssenkrupp in the early part of the current millennium; particularly that of the Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft (HDW) shipbuilding company in 2005. Following a previous period of rationalisation, the former HDW shipyard in Kiel is currently the sole location for submarine construction in Germany, employing some 3,100 workers. tkMS claim that this makes the facility Germany’s largest shipyard. Like Naval Group, tkMS’s submarine business is supported by a strong indigenous supplier network. This includes wholly-owned subsidiary Atlas Elektronik (combat management systems, sonar and torpedoes) and sub-contractors such as Hensoldt (optronics), Rolls-Royce’s MTU (diesel generators), and Siemens (electric motors and AIP propulsion).

Credit: tkMS

tkMS submarine’s business is focused on the construction of diesel-electric submarines, mostly also equipped with auxiliary AIP-propulsion systems. Although it has a long track record of supplying advanced submarines to the German Navy – most recently the Type 212 AIP-equipped series – it has typically been more heavily reliant on export contracts than any of the other European manufacturers. Its considerable success in the global market for submarines can initially be traced to the popularity of the well-known Type 209, which was developed in conjunction with the design house IKL as long ago as the 1960s and has remained in production into the current decade. More recently, tkMS has also been bolstered by the widespread acceptance of Siemens’ Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) fuel cell technology for AIP-propulsion. This was first introduced operationally in the Type 212A submarines built for Germany and Italy but, to date, has gained most sales from the export-orientated Type 214 design. The majority of the latter boats have been built by overseas shipyards under licence.

Although tkMS is currently in the course of completing export contracts for Israel (‘Dolphin II’) and Singapore (Type 218SG), its most important current project is for the new Type 212CD (‘common design’) class. Derived from but significantly larger than the previous Type 212A iteration, these are being built in Germany for both the German and Norwegian navies under a collaborative programme. A contract valued at EUR 5.5 billion was signed for an initial six boats in July 2021 in what tkMS claimed was its largest-ever award to date. Four of these will be for Norway and the other two for Germany. Their construction will be supported by investment of EUR 250 million in improved production facilities at Kiel. Fabrication of the lead Norwegian submarine commenced in September 2023 for planned delivery in 2029, with completion of the contract expected in 2035. However, Norway’s quadrennial Long-term Defence Plan for the period through to 2036 that was announced in April 2024 envisaged procurement of between one or two additional members of the class. Moreover, Germany’s ‘Vision 2035+’ force structure plan envisages the operation of between six and nine submarines in the medium term. As such, it seems that the Type 212CD construction will be extended beyond this date.

The likely growth in the scope of the Type 212CD programme – coupled with further existing and potential export contracts that include a firm order for three additional submarines for Israel – have resulted in questions as to whether the previous process of rationalising tkMS’s construction infrastructure has gone too far. In June 2022, it emerged that tkMS had acquired the Wismar shipyard from the insolvent cruise shipbuilder MV Werften as a possible additional location for submarine construction. At present, it is unclear as to the extent to which this intention will be realised amongst reports that Wismar might be re-purposed to construct other types of vessel. Additional uncertainty arises from the planned demerger of tkMS from the wider thyssenkrupp group under a plan revealed in March 2023. As of September 2024, discussions to implement the business’s sale were still ongoing.

Italy: Fincantieri

Current Italian submarine construction is carried out by Fincantieri at the Muggiano shipyard near La Spezia in northern Italy. The end of the Cold War saw Italy decide to forego a fully national submarine capability in favour of adopting the German Type 212 design for its future underwater needs under a collaborative programme. This saw limited modifications to what was an existing German programme to meet Italian requirements for Mediterranean operation, leading to the Type 212A designation. Two pairs of these submarines were delivered to the Italian Navy as the Todaro class in separate batches during 2006-07 and 2016-17 respectively.

Credit: Fincantieri

Fincantieri is now in the course of evolving towards re-establishing a fully indigenous submarine design and manufacturing capacity through construction of the Type 212 NFS (‘near future submarine’) design. This is essentially an Italian development of the previous Type 212A. Fincantieri signed a contract for two of these new boats in February 2021 and options for an additional pair have subsequently been exercised. Construction of the lead unit commenced in January 2022 to meet targeted delivery in 2027. The design incorporates a number of design modifications produced by the Italian company, which is design authority and prime contractor for the class. The Type 212 NFS also incorporates significant levels of equipment sourced from the Italian supply-chain.

Construction of the Type 212 NFS form part of a phased approach that will subsequently transition to a further-evolved Type 212 NFS EVO prior to production of a fully-national new generation submarine (NGS) in the 2040s. In the interim, Fincantieri has also strengthened its industrial base with the EUR 415 million acquisition of Leonardo’s Underwater Armament Systems business in May 2024. Despite this progress, Italy arguably has a less-developed network of component suppliers than many of its European rivals and this could place it at something of a competitive disadvantage. It also has no recent track record of exporting full-sized submarines, leaving the scope of its future activities largely dependent on Italian Navy requirements and funding unless it can break into the wider, international market.

Spain: Navantia

Although Spain has a long track-record of submarine construction, the vast majority of its historic production has been formed of license-produced, overseas designs. The Cold War era saw particularly close collaboration with what is now France’s Naval Group; notably with respect to the S-60 (licensed Daphné) and S-70 (Agosta) classes. This track-record of co-operation subsequently played an important part in Spanish industry becoming a junior partner in a joint venture to produce the export-focused ‘Scorpène’ design that was finalised in 2001. Spanish-based construction activities for all these submarines took place at the shipyard at Cartagena, which remains the production centre for Navantia’s submarine business.

Credit: Navantia

A major change in the Spanish submarine industry’s strategic direction took place with the decision to develop the indigenous S-80 class under a programme that received final government approval in September 2003. As well resulting in the breakup of the previous collaboration with France, this exposed Spain to the huge challenges involved in the fully independent design and construction of a complex, modern submarine. Accordingly, the programme encountered significant difficulties that were most evident in an increase in weight that dangerously impacted reserve buoyancy. The result was a major re-design and hull-extension with the assistance of the United States’ General Dynamics Electric Boat (GDEB). This ultimately pushed back delivery of the lead boat, Isaac Peral, until November 2023. The other three members of the class remain under construction at Cartagena.

Whilst the S-80 programme has proved a problematic and expensive one, its ultimate implementation has provided Spain with a sovereign submarine design and manufacturing capability that was previously lacking. This has included significant steps in developing the capabilities of an indigenous supply chain. The future of this capacity now depends on the willingness of the Spanish government to fund further submarine orders for the Spanish Navy, as well as Navantia’s success achieving export sales. Whilst several opportunities have been pursued, overseas nations demonstrated an understandable reluctance to commit to the company’s designs before the lead member of the S-80 class was actually delivered. It should also be noted that Spain likely still has the heaviest reliance on overseas suppliers for submarine components amongst European shipyards, with America’s Lockheed Martin (sonar and combat management system elements) and Britain’s Babcock (weapon handling system) being amongst key contractors for S-80 construction.

Sweden: Saab

Sweden is currently in the process of attempting to revitalise its national submarine industry under the ownership and direction of national defence conglomerate Saab. The group acquired the then-Kockums shipbuilding business in 2014 after Kockums’ previously successful submarine business has been allowed to atrophy during a period of, first, HDW and, then, tkMS ownership. The acquisition was driven by the Swedish government in reflection of the crucial importance of submarines in Sweden’s overall defence architecture.

Credit: Saab

Since acquiring Kockums, Saab has been working to resurrect indigenous submarine production at the Karlskrona shipyard. The facility has undertaken a series of life-extensions of the three existing Gotland class submarines in preparation for construction of the next generation A26 Blekinge class, two of which were ordered in 2015. In a sign of the very large amount of work needed to resume Swedish submarine production since completion of the Gotland class boats in 1997, it was only in June 2022 that a keel laying ceremony for the lead A26 was held. This challenge is also reflected in a delay in the planned delivery of the initial boat from 2022 to 2027 and an increase in the production contract’s cost from SEK 7.6 billion to SEK 12.8 billion (approximately USD 1.3 billion).

Despite these teething problems, the future of Sweden’s submarine sector appears to be assured by a continued requirement for domestically produced boats. This is reflected in Saab’s receipt of a government contract in December 2023 to conduct concept development studies for future underwater capabilities. These studies likely encompass plans to replace the Gotland class during the 2030s with a new design that has sometimes been referred to as ‘U-båt 2030’. Saab has also been pitching a series of submarine designs derived from the A26 in the export market but received a major setback in March 2024 when its joint proposal with Damen for the Netherlands’ submarine replacement programme was beaten by Naval Group’s bid. Whilst Saab continues to pursue other export possibilities, the advantage previously provided by its Stirling AIP technology has arguably been eroded by progress with competitor systems. Given also the economies of scale enjoyed by larger submarine manufacturers, Saab may struggle to achieve export success.

United Kingdom: BAE Systems

British submarine construction is carried out by BAE Systems at its shipyard in Barrow-in-Furness in north-west England. Like France, the British Royal Navy decided to phase out its diesel-electric submarines at the end of the Cold War. In the absence of a competitive diesel-electric design for export markets, this has left Barrow dedicated solely to building nuclear-powered boats. The United Kingdom does, however, have an extensive network of submarine component manufacturers, including Babcock (weapon handling equipment), Rolls-Royce (reactors) and Thales UK (sensors). Some of this equipment has achieved considerable export success with countries such as South Korea and Spain that still lack the ability to produce some submarine components indigenously.

Credit: BAE Systems

Again in similar fashion to France, the United Kingdom’s determination to maintain an underwater nuclear deterrent has underpinned the country’s submarine enterprise. However, this did not save the industry from considerable rationalisation at the Cold War’s end. Notably, the Barrow-in-Furness workforce fell by over three quarters (from 13,000 to 2,900) in the decade between 1992 and 2002. An associated loss of skills caused significant problems with completing the programme for Astute class nuclear-powered attack submarines, for which initial construction contracts were signed in 1997. Five out of a projected class of seven boats have been delivered to date, with the other two in the later stages of construction.

The industry’s fortunes have recovered with the need to renew the strategic submarines that form the United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent. Production of the first of a planned four Dreadnought class submarines commenced at Barrow in October 2016 under what is known as the ‘Successor’ programme. The massive project has been costed at GBP 31 billion (plus a GBP 10 billion contingency) and has necessitated the wholescale revitalisation of the shipyard’s capacity. This has included extensions to the 260 metre long Devonshire Dock Hall where submarines are assembled, as well as a ramp up of the yard’s workforce to a current level of around 13,500 personnel.

Whilst Dreadnought class production is already likely to sustain BAE Systems’ submarine business throughout the next decade, longer-term production will be assured by the SSN-AUKUS nuclear-powered attack submarines being built for the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy under the September 2021 trilateral AUKUS defence security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. All members of the class destined for Royal Navy service will be constructed in Barrow, from where the first boat will be delivered at the end of the 2030s. The project has been reported to require further expansion of shipyard facilities and another increase in workforce to a peak of around 17,000. Although the Royal Australian Navy SSN-AUKUS submarines will be assembled locally in Osborne, South Australia, the British submarine supply chain will benefit from significant business from their construction. Notably, Rolls-Royce will produce the nuclear reactors for all the class at its facility at Raynesway in Derby.

Competition on the Horizon

This short overview of the current European submarine industry reveals a buoyant sector marked by strong increase in demand and associated investment in facilities and the workforce. The industry is also supported by the involvement of major defence and shipbuilding groups with large financial resources and by governments that have displayed a long-term commitment to indigenous submarine manufacture. The position of those manufacturers – BAE Systems and Naval Group – producing submarines that form a critical element of their home countries’ nuclear deterrence looks particularly secure.

There are, however, a few clouds on the horizon. In addition to the inevitable strains associated with expanding after a long period of subdued demand, the threat posed by new market entrants cannot be discounted. This is particularly relevant for those manufacturers focused on – or seeking to develop – an export-based business model. For example, Germany’s previous support for South Korean and Turkish industry through licensed production of the Type 209 and Type 214 submarines is now seeing both countries starting to emerge as competitors on the world stage. Whilst Turkey has yet to produce a national submarine, its industry has undertaken life-extension work for Pakistan. South Korea is further advanced, having sold submarines to Indonesia and emerged as a realistic contender for many current programmes, not least in Poland. Europe clearly has work to do if the good days of the submarine industry’s resurgence are to continue.

Conrad Waters