The Russian aggression against Ukraine has a bitter twist to it – one of the belligerents, Russia, is the world’s largest holder of small ‘tactical nuclear weapons’, along with its more publicly-discussed strategic nuclear deterrent force. As this conflict continues to rage, it is worth discussing these tactical nuclear weapons and their implications.

Tactical nuclear weapons are miniaturised nuclear warheads intended for use with carrier munitions such as artillery shells, mortar shells (the Soviet Union had a 240 mm nuclear mortar), demolition charges, rocket and missile warheads designed for battlefield use, aerial dropped bombs, depth charges, and torpedoes. As a general rule of thumb, these are weapons of less than 10 kt yield – translating to an explosive force of ≤10,000 tonnes of the conventional explosive TNT. Russia is believed to still maintain an arsenal of many hundreds of such weapons, although their inventory is the subject of much speculation.

The US Army and US Navy got entirely out of tactical nuclear weapons, with the remaining US weapons in this category currently in the hands of the US Air Force. These consist of a few hundred B61 aerial bombs, some of which are forward deployed at US bases overseas. The B61s are ‘variable yield’ weapons and if you (literally) dial the yield to the lower options, they could be used as tactical weapons. At the upper end of their yield, they are too big to be considered ‘tactical nukes’.

Aspects of small nuclear weapons

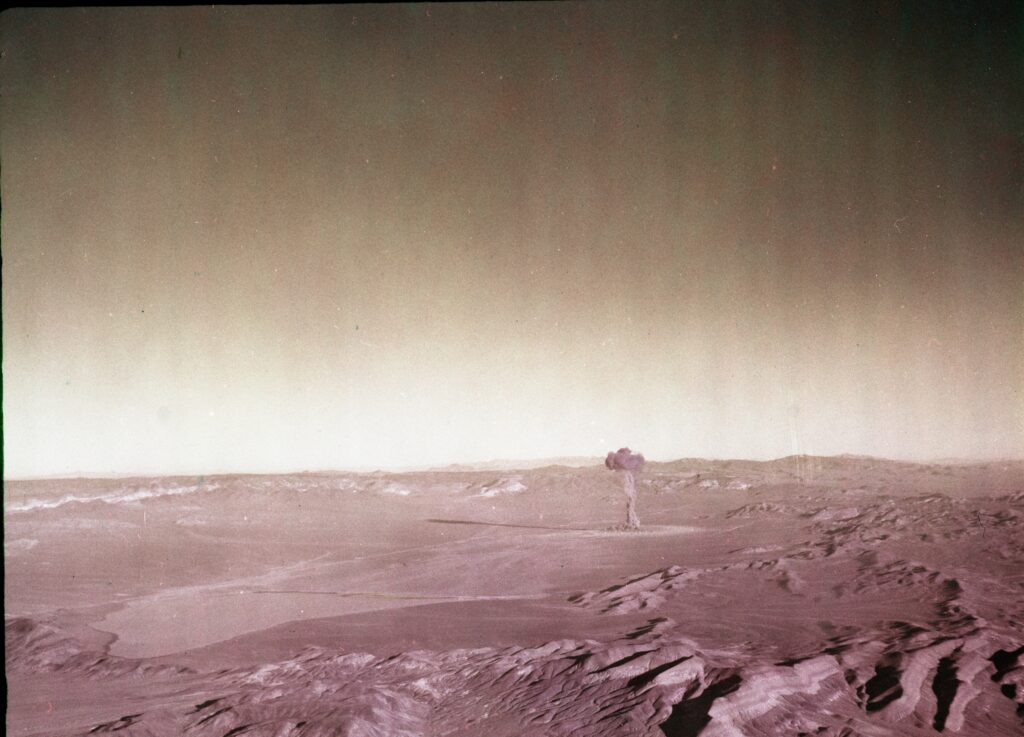

Non-specialists have simplified notions of nuclear weapons. After all, few people alive have ever seen one go off. TV, film, and popular literature have spread both correct and incorrect notions of how they work and what sort of effects they have. Let there be no mistake about it, the strategic nuclear weapons that sit on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) or in stealthy submarines are city-enders. They are many times more powerful than the crude-but-effective nuclear weapons that demolished Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tactical nuclear weapons on the other hand are much smaller. The strength of weapon that destroyed those two Japanese cities is basically at the far top end of the scale for tactical nuclear weapons. We are talking about weapons that range from perhaps half the yield of those original weapons down to yields that measure in the tens of tonnes of TNT equivalent. By way of example, the smallest tactical nuclear weapon yield in the US arsenal was the W-54 (retired decades ago), which had yields as low as 10 tonnes of TNT equivalent. A conventional explosion of that magnitude could easily be made by a payload towed by a commercial semi-trailer truck. There have been, and no doubt will be, conventional explosions that are larger in explosive yield than small nuclear weapons.

What does this mean in practical terms? First of all, the radius of total or partial destruction from heat and blast is much smaller than many people assume. For example, the US B61 bomb, set to its lowest yield of 0.3 kt, will only physically destroy buttoned-up tanks at a radius of about 100-120 m. For the smallest of nuclear weapons, less than about 2 kt, the biggest radius of damage is not blast or heat, but direct gamma and neutron radiation. This is the sort of thing that is mitigated by, say, being in a bunker or in a tank. Another factor is the electro-magnetic pulse (EMP). Long associated with nuclear weapons employment, given the yield and altitude of tactical weapons, the EMP is very small compared to strategic weapons detonated at high altitudes.

Offensive doctrine

The continued existence of tactical nuclear weapons in the hands of a party (Russia) to the largest ground war in recent decades means that there needs to be some consideration of offensive tactical nuclear doctrine. What are these weapons actually meant to be used for? While the finer details of Russian offensive doctrine remain secretive, we can draw some conclusions from old Soviet and American doctrine.

First and foremost, the existence of tactical nuclear weapons can arguably serve as a deterrent much in the same way as strategic nuclear weapons. Though the extent to which this is true is debatable as, from a technological standpoint, the entry point into nuclear weapons are the larger weapons more suited to strategic aims.

From a more tactical perspective, small nuclear weapons are meant to serve as a replacement for much wider and deeper use of conventional weapons. In other words, a single nuclear aerial bomb or artillery shell replaces thousands of conventional shells or bombs in some scenarios. It might take a serious artillery campaign involving dozens or hundreds of howitzers to blunt the advance of a tank brigade, or a series of bombing sorties to take out a key bridge, but a small handful of sub-kiloton nuclear warheads might save an awful lot of time. For both the US Army and the Soviet Army, Cold War doctrine often treated tactical nuclear weapons as very large munitions, their sheer explosive yield acting as substitutes for precision. In naval terms, lest we forget maritime affairs, they are basically the only type of payload that can assuredly take out a US aircraft carrier or large amphibious ship. Modern military doctrine often talks about ‘shaping’ the battlefield, but use of nuclear weapons against bridges, dams, and airfields literally does shape the battlefield.

Passive defensive tactics and techniques

One of the things that this correspondent learned as a young CBRN defence officer in the early 1990s was that the idea that you cannot defend against tactical nuclear weapons is, in fact, a defeatist fallacy borne out of ideas of scale that apply more to strategic weapons, which are truly city-busters. As noted above, lumping all nuclear weapons into the same bin is not actually a helpful approach. There are numerous tactics and techniques to reduce an army’s vulnerability to tactical nuclear weapons.

In terms of infantry forces, the old tactic of entrenchment, particularly with overhead soil cover or sandbags, greatly reduces the radius of vulnerability for soldiers. A lethal dose of radiation at, say, 600 m, can be mitigated down to a nuisance level of radiation exposure by just a metre of soil. Dispersal and entrenchment can, quite practically, make the tactical nuclear artillery shell a substitute for hundreds of conventional shells, not thousands, thus calling into question the logic of their employment. Entrenchment with overhead cover and dispersal of key forces until they need to be concentrated together is already a lesson learned in the Ukraine conflict due to conventional lethality; in fact, some such countermeasures against drone warfare, also provide nuclear hardening as a second-order effect.

Military CBRN defence has often, in recent decades, neglected the R and N, but good CBRN defence equipment and practices are part of a good casualty-reduction strategy. Good awareness of weather conditions (which you need anyway for small drone operations and precision artillery) gives commanders an idea where the fallout (if any) from nuclear weapons employment will end up. Combined with well-established hazard prediction schemes, both manual and automated, this gives the defender an idea where and when post-attack hazards will be significant. For tactical weapons, many of which need to operate as air-burst weapons to maximise their immediate radiation, blast, and thermal effects, downwind fallout might even be negligible or only a matter of a few kilometres. Yet skilled CBRN specialists have the tools to estimate where those few kilometres will be.

Contamination avoidance is backstopped by radiation detection and dosimetry. Military radiation detection (discussed in issue number 1-24 of this magazine) lets commanders know where a hazard may be, and the magnitude of the hazard. It also can tell if equipment is contaminated or not, allowing judicious use of decontamination assets. Dosimetry, often neglected in recent decades, allows for monitoring of just how much radiation troops have been exposed to. In theory, this allows for judicious decisions on rotating troops or taking defensive measures. Armies serious about the tactical nuclear threat can and should dust off their radiation detection and dosimetry technology.

Finally, there is the prospect of nuclear explosive ordnance disposal (EOD). Given the sophistication of tactical nuclear weapons and the daunting maintenance burden that they incur, there is a non-trivial chance that some of the Russian arsenal fails to function. In this vein, the prospect of tactical nuclear duds is something that needs to be addressed; this is an area where robotics holds more promise than a long stick – though the long stick still has a surprising number of uses in EOD scenarios.

Active defence

Passive defence increases the ability of the target to endure damage, but an active approach to preventing the use of such weapons is probably preferrable. Obviously, air and missile defence systems are a logical countermeasure against air-dropped bombs, missiles, and rockets. Robust use of such systems works as both a direct countermeasure and a deterrent.

Another factor is counter-battery fire. If the prospect of tactical nuclear weapons being used becomes of direct concern, NATO doctrine will more or less drop every other category of target and the delivery systems for nuclear weapons become the primary target class. Dumping every category of firepower into targeting a fairly narrow number of delivery systems would be very effective if combined with thorough situational awareness and target acquisition. Even in a disproportionate conflict, there would only be a finite number of rocket launchers, artillery tubes, airfields, and the like that could deliver such weapons. Furthermore, it is exceedingly unlikely that tactical nuclear weapons are routinely lurking around in the ammunition trucks. Special transport from secure storage, with special security, may be something that intelligence and surveillance assets could discover and target; alongside this, conventional strikes to degrade the transport network to get weapons to the firing units would also be of value. Electronic warfare (EW) would be of value too – disrupting the ability to send orders to units, geolocation of firing units, and general erosion of command and control (C2) are within the remit of EW.

Finally, there is the prospect of deterrence. Is the use of nuclear weapons in a tactical sense the thin end of a wedge that leads to strategic nuclear warfare, and thus ending modern civilisation as we know it? For decades this was the arms control argument against tactical nuclear armaments and one embraced by many governments, both left and right of centre. Indeed, it was George Bush senior who started the process of getting the US mostly, but not completely out of the business of tactical nuclear weapons, largely for this reason. In this day and age of ‘red lines’ observed more in their breach than in practice, perhaps this is an area where countries with strategic weapons, such as France, Britain, and even China can lay down a firmer red line.

Dan Kaszeta

![Pilots for soldiers A US Soldier assigned to 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division operates the Kraken during exercise Spectrum Blitz 25 at the Hohenfels Training Area, Germany, on 11 April 2025. [US Army/Sgt Collin Mackall]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Spectrum-Blitz-25-US-ArmySgt-Collin-Mackall-Kopie-218x150.jpg)