Two decades ago, the US Army and US Navy began developing the non-line-of-sight launch system (NLOS-LS, aka ‘Rocket in a Box’) as a modular firing system housing 15 vertically launched 280 mm rockets in a container. The Army planned to mount the system on flatbed vehicles, while the Navy hoped to add much-needed firepower to the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS). By 2011, both services had terminated the programme over technological setbacks and poor performance.

Containerised munitions

The concept of containerised naval weapon systems is currently gaining traction with several Western nations. They can be secured to open deck spaces on any vessel, from naval auxiliaries to merchant ships and to larger unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). Since the containerised weapon systems are self-sufficient and include integrated fire control systems, they can be quickly loaded onto ships and operationalised with minimal reconfiguration. The number of combat-capable vessels can thus be increased at very short notice. When the requirement for the additional strike capability is over, the ships can quickly return to their original mission configuration.

The concept is particularly suited for navies which need to increase the number of combat-capable platforms at an affordable cost and over a short timeframe. The US Navy, in particular, has been adamant about the need for distributed maritime operations (DMO), especially in expansive theatres of operations such as the Indo-Pacific. To date, long-range anti-ship and land-attack missiles remain the prerogative of dedicated surface combatants ranging from corvettes to cruisers. While powerful, these sophisticated vessels are available in limited numbers. Enabling additional missile launch platforms would permit dispersed attacks against enemy naval groups and land targets, increasing the potential to inflict damage while also straining enemy defences. Potential platforms include lightly-armed warships with open deck space as well as auxiliary vessels including cargo craft. Leasing or purchasing merchant vessels to serve as containerised missile carriers is another option.

While the vessels equipped with containerised munitions would be slower and less robust than dedicated major combatants, modern standoff weapons could be launched from sufficient range to minimise risk; dispersal of firing platforms would also make enemy counter-strikes more difficult. In this context, it should be noted that the containerised weapons concept includes the option of equipping vessels with air defence missiles as well as loitering munitions optimised against surface threats, adding a force protection element.

US Navy – Mk 70 Payload Delivery System

The US Navy has chosen to equip the Independence class and Freedom class littoral combat ships (LCSs) with the Mk 70 mod 1 Payload Delivery System (PDS). Developed by Lockheed Martin, the Mk 70 PDS is incorporated into a 12 m (40 ft) ISO container with four Mk 41 VLS cells and a launch erector system placed within the container. In principle, any munition capable of launching from a deck-embedded VLS cell aboard a cruiser or destroyer can be loaded into the Mk 70. To date, the launcher is certified for the SM-6 missile and the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM). Additionally, Lockheed Martin tested the launcher with the Patriot PAC-3 MSE surface-to-air missile (SAM) in May 2024, downing a cruise missile representative target.

The Navy has not categorically stated how many Mk 70 PDS would be carried per LCS, but in 2024 Lockheed Martin presented a concept showing three systems (for a total of 12 VLS cells) on the flight deck of a Freedom class vessel. The drawback of this full load-out on an LCS would of course be the inability to conduct helicopter operations as long as the containers are in place, a restriction that would not be as significant on ships with larger decks.

According to Lockheed Martin, the Mk 70 (which is also configured for truck-launched operations for the US Army) “enables rapid deployment of [mid-range precision fires] offensive capability to non-traditional platforms and locations”. It could be deployed in the future on any vessel with sufficient free deck space – including amphibious ships, Expeditionary Support Base units or large unmanned surface vessel (USV) – to provide them with powerful anti-ship, land-attack or air defence systems. This would enhance force protection for these otherwise weakly-armed vessels, while expanding their offensive options. Being containerised, it can also be truck-mounted and landed (via Ro-Ro ramp or landing craft), making it a ‘dual-use’ weapon employable from ship or shore and back again within one deployment.

SH Defence – CUBE System

Danish firm SH Defence offers the CUBE System which promises enhanced modularity and flexibility for multi-mission vessels. The many mission module options in the CUBE System portfolio include 6 m (20 ft) and 12 m (40 ft) ISO containers housing anti-ship missiles (ASM), torpedoes for anti-submarine warfare (ASW), and loitering munitions.

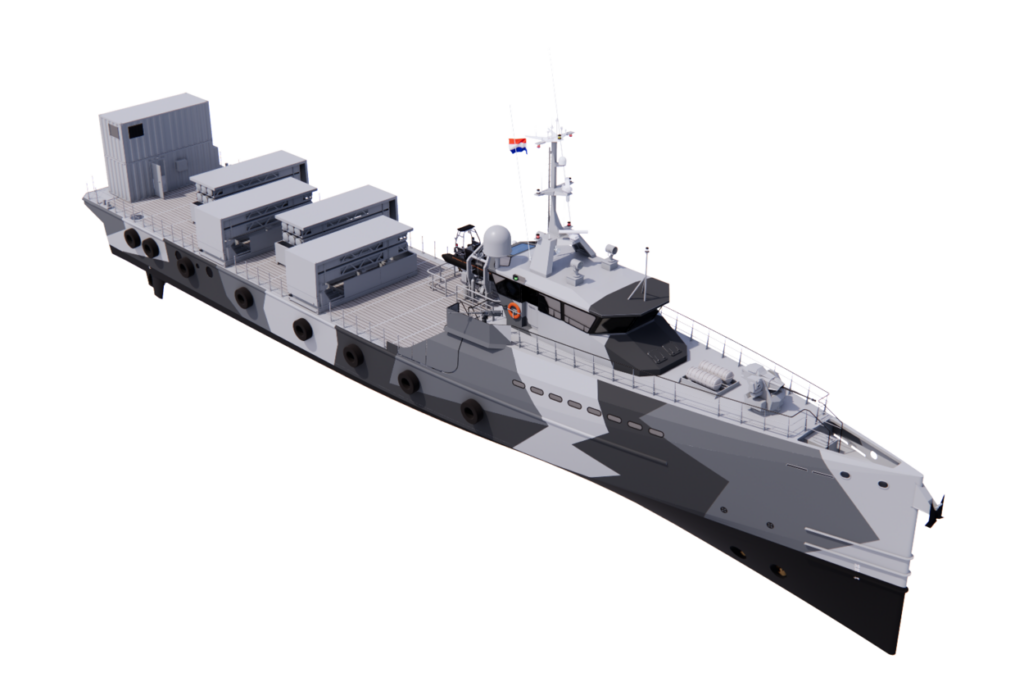

RNLN Multifunction Support Ships

The Royal Netherlands Navy will arm its new Multifunctional Support Ships (MSS) with containerised missiles. The 28 × 8.5 m aft deck can accommodate a variety of containers, with concept images showing four 6 m (20 ft) ISO containers side-by-side, in addition to two stacked containers for electronics and control systems. As of early 2025, it is expected that the containers will be bolted to the deck, although other options – including the SH Defence CUBE system – could still be applied. The MSS is intended as an escort for the De Zeven Provincien class air defence frigates, and will provide additional firepower to protect the primary combatant (and other vessels) from missile and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) saturation attacks. The frigates will provide targeting data and command and control (C2) for the MSS’s weapons. The primary weapon for the MSS will be the IAI Barak ER SAMs which can defeat aircraft, cruise and short-range ballistic missiles at ranges up to 150 km and altitudes up to 30 km. These will be supplemented by the IAI Harop long-range loitering munition which can strike land targets to support amphibious operations.

Rheinmetall Containerised Launch System

In 2024, Rheinmetall, in collaboration with UVision, presented its own concept of a containerised launch system consisting of 126 cells for Hero-120 loitering munitions. The image showed a truck-mounted version. The container had no top, and was subdivided into three arrays with 42 cells each. Each cell had its own cover which the loitering munitions could penetrate during launch. While the displayed configuration was vehicle-mounted, the system appears well suited to installation aboard a suitable naval vessel. Rheinmetall itself has praised the Hero-120’s ability to easily integrate into existing naval C2 and target-acquisition systems, “[bringing] highly affordable solutions to the growing challenges of the complex naval arena”. Potential operational scenarios include launching offensive swarms to overwhelm defences of an enemy vessel (including ‘blinding’ a major warship through a saturation attack against its sensors) or counterattacks to neutralise incoming UAVs/USVs or manned fast inshore attack craft (FIAC) operating in swarms. The subdivision of the container implies that the system can be mounted in containers of various size, with different numbers of effectors, to accommodate smaller and larger vessels as well as different operational scenarios.

IAI – LORA

Israel Aerospace Industries’ long-range artillery (LORA) tactical ballistic missile was first introduced at Eurosatory 2006, and is thought to have entered service with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in 2007. IAI cites minimum/maximum ranges of 90 km to 430 km (49 NM to 230 NM). It was originally designed as a truck-mounted mobile weapon system with four sealed missiles per containerised launcher.

Special considerations

Special legal aspects must be considered with regard to housing long-range weapons in civilian-appearing cargo containers. This is irrelevant when the missile containers are mounted on clearly designated warships such as the LCS or the MSS. However, some analysts have proposed quickly and cheaply expanding war fleets by acquiring merchant vessels and arming them with containerised missiles. One argument made in this context is that such vessels would be able to sail in or near conflict zones (including through chokepoints) with little risk of detection, as their silhouette would blend in with commercial traffic. However, unless the vessels are clearly designated as combatants, such a practice could quickly enter a legal grey zone. As Captain Pedrozo emphasised, only warships and military aircraft may exercise belligerent rights during an international armed conflict (IAC) at sea. “Other vessels, such as naval auxiliaries and merchant vessels, even when carrying out support services for the naval forces, are not entitled to engage in belligerent acts during an IAC, but they may defend themselves, to include resisting attacks by enemy forces.” Conversely, non-belligerent vessels may not be targeted as long as they refrain from belligerent acts.

Again citing Captain Pedrozo, merchant vessels can legitimately be converted into warships, but they must be clearly designated as such through external markings and be publicly registered in the list of warships. They must also be under direct command of military officers. In addition to respecting the rule of law, this would also preclude an opponent categorically targeting merchant vessels prophylactically under the assumption that they might be disguised belligerents. While most Western maritime powers would be expected to broadly comply with international norms regarding openly distinguishing between military and civilian vessels, in China, which maintains the world’s largest merchant fleet, a 2016 law requires merchant carriers to support “strategic projection” by the armed forces. Given past instances of disregard for international norms by China, such as various threatening acts toward other navies in the South China Sea, some analysts worry that the country might deploy unmarked merchant vessels as missile platforms. Whether designated or not, the sheer size of China’s power projection potential will require a major and timely expansion of armed platforms by western nations. Given budgetary constraints and the long lead-time for military shipbuilding, this goal seems most readily achievable through systematic procurement of non-traditional vessels for military purposes.

Sidney E. Dean