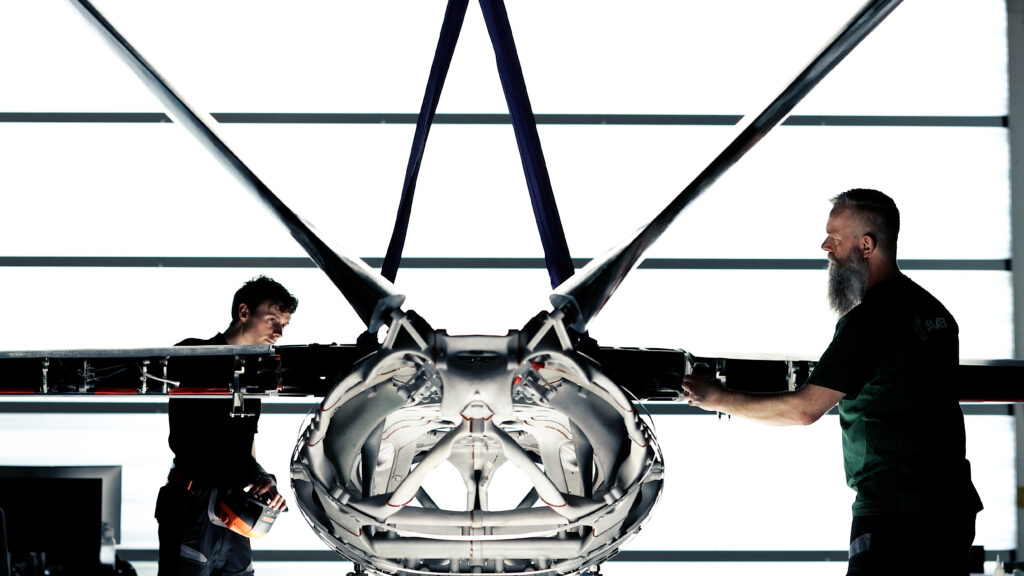

Saab announced on 10 December 2025 that it has created the world’s first software-defined aircraft fuselage.

In a project led by The Rainforest – the company’s internal start-up focused on transformative innovation – Saab has worked with California-based digital manufacturing specialist Divergent Technologies to design and manufacture the 5 m fuselage of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that is set to make its first flight on 2026.

Comprising 26 unique parts, the fuselage was developed and realised with no unique tooling or fixturing but instead utilising Divergent’s software-defined manufacturing assets, which combine industrial-rate laser powder fusion additive manufacturing with universal robotic assembly processes.

In an online briefing to select journalists on 9 December, Marcus Wandt, head of group strategy and technology at Saab, outlined the overall strategy behind the effort.

“We can see that we have the need for continuous capability development and short iteration loops, and sometimes to quickly achieve results,” he explained. “And sometimes because we don’t really have the time to find all the data and know exactly what we want to build before starting to build this, we have to start the build right away, and by having short iteration loops and the technology that enables that, we can start moving without taking big risks for the warfighter, or for industry or for governments.

“Our AI strategy has three parts,” said Wandt. “One is mission advantage, the next one is augmented design and engineering, and then we have smart operations. Today we’re going to talk about augmented design and engineering and how we are doing that in the modern way.”

Axel Bååthe, head of The Rainforest, noted the work Saab has been doing with its Gripen E fighter. Because the Gripen E features verifiably separated flight-safety critical and mission-critical software, together with an avionics platform that is computer hardware-independent, Saab’s aerospace engineers can, as Saab puts it, ‘Code in the morning, fly in the afternoon’ with any software upgrade to the aircraft. Moreover, Saab collaborated with German defence technology company Helsing to put its Centaur artificial intelligence (AI) agent integrated into a Gripen E, with the result that the aircraft made its first flight with an AI agent in control on 28 May 2025.

“The pace and adaptability of innovation becomes so important in what we’re doing,” said Bååthe. To take this to the next step, he explained, requires flexibility in manufacturing hardware just as much as software, whereby Saab moves beyond ‘Code in the morning, fly in the afternoon’ to ‘CAD [computer-aided design] in the morning, fly in the afternoon’.

“This is, of course, a vision that will take years to realise for the whole system, but we are taking steps already today to realise parts of this journey,” he said.

“In a traditional fuselage we’re quite defined and limited by tooling,” Bååthe explained, “so if we want to be more flexible we need to find a way to manufacture that is more defined by code – and of course, innovations in terms of robotics and additive manufacturing play a key role in this. We need to be able to manufacture shapes that are limited only really by the algorithm; changing the design requires just updating a file and hitting print.”

“Fuselage geometry is, of course, a limiting factor in traditional manufacturing, where we have to stay close to straight lines and perfect circles, and if we want to do complex shapes it becomes very, very difficult and very expensive,” noted Bååthe. “With a software-defined manufacturing method we can have essentially unlimited freedom; we can have biometric, more topology-optimised structures because we can let the design tools optimise for physics, placing structure exactly where the loads are instead of enabling manufacturing.”

The saving in material waste is also above 90% compared to traditional manufacturing, Bååthe noted, with future production scalable to more than 1,000 units per year.

Cooper Keller, chief programmes and operations officer at Divergent Technology, explained the technology behind the initiative.

“What Divergent has created – and I’m not aware of any other company that has focused on the entire stack – is a truly digital and fundamentally adaptable production system,” said Keller. “We call our system the Divergent Adaptive Production System, or DAPS for short, and it is inclusive of the software that allows the engineers that are most familiar with the vehicle and the requirements of the vehicle to very quickly move from the requirements to a structure that achieves the requirements of that system: the stiffness performance, the durability performance, while also being fundamentally manufacturable using an adaptable production system.

“What we’ve seen in the industry is that it is just far too easy to simply buy a printer, but as soon as you have commissioned that equipment into your factory, you realise that there are hundreds of elements upstream and downstream of that printer that are really required to integrate it into an end-to-end system that allows you to actually deploy manufacturable product … and a structure that can be scaled at rate,” said Keller. DAPS solves this dilemma.

Further to this Keller noted that Divergent has “built a large format laser powder bed machine that is printing likely 15 to 30 times faster than anything else that is seen in industry, and it’s doing so in a factory that is already achieving very, very high utilisation: north of 80% utilisation across our equipment, producing far more output for production programmes”, adding that “We have flight-qualified hardware coming off of this system that is flying in piloted jets.”

Regarding the production/assembly process, Keller said, “We knew very early on that it was not going to make sense to print or to build a printer that is large enough to print the entire fuselage of the aircraft, or to build a printer large enough to print the entire chassis of a vehicle, for example,” said Keller, “so we’ve created the software that allows the engineer to very quickly assess how the parts should be split up into individual constituent elements that can then be assembled using a fixtureless assembly cell.”

Asked by ESD how this fixtureless assembly cell actually joins the components together, Keller declined to go into detail as to precisely how the joining technology works, but noted that the joints “have been fully qualified for safety critical applications in both automotive and aerospace applications”, are fully validated for very unique environments and are at Technology Readiness Level 9 (ie fully mature, proven and operational in a real-world environment).

Divergent currently has a single factory in Torrence, California, but is breaking ground on a second factory this year. Keller added that Divergent “will be scaling to five factories in the continental US over the next two years” and that “in the 2028 timeframe you will start to see us deploy our system in Europe as well”.

Still images and video of the Divergent-produced fuselage during the Saab briefing showed a structure that was almost skeletal in its composition. When ESD asked if this was more than a coincidence, Bååthe replied, “I’m not a structures engineer by trade, but I’m an aerospace engineer from the beginning and, of course, appreciate clever designs. Something that has struck me when working with these types of topology optimisation algorithms is that nature is pretty clever. So I think in some sense it was a surprise that these shapes look this organic and this sort of skeleton like, but on the other hand I think nature is very, very good at optimisation and creating only the structure required per kilogramme of weight that that needs to solve the task at hand. And I think this is what we’re seeing here as well. When we’re unconstrained in the right angles, straight lines, machining operations, it becomes quite skeletal, which is fascinating.”

Keller added, “Our name really was derived from the concept of Darwin’s divergent evolutionary biology: the process where species, with a common ancestor, evolved to distinct forms to adapt to their environments. And that’s precisely what we’re doing; instead of millions of years of predatorial evolution, it’s minutes of super computing and AI evolution, but it’s essentially the same process where you are adapting and evolving for the specific requirements. And that’s why they look organic, they look natural, they look biological, because it’s very much a similar process. It’s being constrained by the same physics that are really driving evolutionary biology.”