On 4 April 2023, Finland completed the final formalities needed to join NATO and became the alliance’s 31st member. When considered alongside Sweden’s pending application for membership, this historic moment marks another milestone in the broader Scandinavian region’s strategic realignment that has followed the return of Russian ‘adventurism’. This process of change is also evidenced in Scandinavia’s accelerating process of naval renewal, which is steadily adapting to new realities in the Baltic and Norwegian Seas. However, maritime reorientation will inevitably be incremental in nature and take time to achieve. This article provides a status report on the naval programmes that are currently underway.

Finland

The lengthy timelines involved in naval acquisitions are visibly demonstrated by Finland’s current flagship naval project, known as ‘Squadron 2020’. This was formally launched in 2015 after several years of preliminary research and development. Its intention was to replace seven of the fleet’s existing major combatants with a quartet of flexible, multi-role corvettes. These will be named the Pohjanmaa class after one of the vessels they will replace. The new construction was planned to run alongside a mid-life upgrade for the Finnish Navy’s four existing Hamina class fast attack craft, which will share much equipment with the corvettes.

It is fair to say that implementation of the ‘Squadron 2020’ concept has not progressed as smoothly as was initially hoped. This is likely due to the challenges involved in developing an entirely new design to a demanding, multi-role requirement, as well as the need to refresh warship construction expertise at builder Rauma Marine Constructions (RMC) after a considerable gap. A contract for the class’s assembly was signed with RMC in 2019 after some delay. This envisaged fabrication starting in 2022, the first corvette commencing trials in 2024 and all four ships being delivered by 2028. Although good progress was achieved in making key equipment selections for the new corvettes, it became increasingly apparent that there were problems in finalising detailed design and making a start on construction.

On 31 March 2023, the Finnish Navy released an update on the programme’s status. Reporting that the corvettes’ design was nearing completion, it also announced a slight increase in length (119 m) and beam (16 m) over previous parameters. Displacement will be 4,300 tonnes. These changes were essentially adopted to improve stability and to add a margin to allow for increases in payload over the ships’ service lives. With conclusion of the design process imminent, the navy was also able to provide an update in planned assembly. It is now intended to start fabrication in the autumn of 2023 and commence sea trials of the lead ship in 2026. The entire programme will be completed by the end of 2029. In effect, this amounts to a delay of around two years compared with previous plans. The programme is also experiencing material increases in its projected cost over an original estimate of EUR 1.3 Bn.

Credit: Finnish Defence Forces

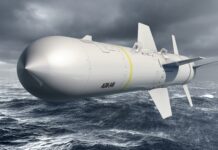

Despite these problems, the Pohjanmaa class will undoubtedly mark a step change in Finland’s naval capabilities when they arrive at the end of the decade. In particular, they will make a significant contribution to the concept of ‘unified naval striking power’ articulated in the current ‘Merivoimat 2032’ (Navy 2032) operational plan. Notable equipment selections include IAI’s ‘Gabriel V’ surface-to-surface and Raytheon’s Evolved SeaSparrow Missile (ESSM) surface-to-air weapons. These provide a marked uplift in the capabilities installed aboard previous-generation ships. Importantly, the new vessels will also be larger and have improved sea-keeping qualities compared with their predecessors.

This will enhance the navy’s capacity to contribute to a wider range of NATO operations.

Meanwhile, much better progress has been achieved with the Hamina class mid-life modernisation, which has a strong anti-submarine warfare (ASW) emphasis. Work on FNS Pori, the fourth and final vessel to be upgraded under the project, was completed by lead-contractor Patria in September 2022. In addition to the ‘Gabriel V’, Saab’s 9LV combat management system and Torped 47 ASW torpedo will be amongst systems shared with the corvettes. This will streamline logistical and training requirements.

Although there has been public speculation about Finland regaining a submarine arm – a capacity lost in the aftermath of the Second World War – this looks unlikely in the foreseeable future given the significant effort that will be required to bring ‘Squadron 2020’ into reality. Instead, other procurement is likely to be focused on less prestigious but still vital capabilities. For example, deliveries of a new series of 22-tonne ‘Jurmo’ class fast landing craft are currently underway from local builder Marine Alutech. Plans for replacement inshore minehunters are also well-advanced.

Sweden

Whilst the prospect of a Finnish submarine flotilla seems remote for the foreseeable future, the renewal of Sweden’s underwater assets is currently the main focus of its own naval procurement plans. In similar fashion to ‘Squadron 2020’, these have a lengthy history that can be traced as far back as the ‘U-båt 2000’ (Submarine 2000) studies of the immediate post-Cold War era. The programme finally took tangible shape in 2015 when the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration (FMV) signed two linked contracts with Saab covering the modernisation of existing submarines and the construction of new boats.

The modernisation agreement initially focused on mid-life upgrades for two of the three existing A19 Gotland class. As well as ensuring the maintenance of an effective Swedish underwater arm, this was intended to de-risk the project for the new boats by overhauling the country’s neglected submarine infrastructure and ‘proving’ much of the technology that would be used in their design. The SEK 2 Bn (EUR 180 M) upgrade appears to have gone largely to plan, being extended to cover the third member of the A19 class as a result of Sweden’s current ‘Totalförsvaret 2021-2025 (Total Defence 2021–2025) regime. A SEK 1 Bn (EUR 90 M) contract to undertake the work was signed with Saab in March 2022.

Credit: Saab AB

The contract for the new submarines is a much larger endeavour, amounting to SEK 7.6 Bn (EUR 670 M) when initially signed in 2015. It involved the construction of two A26 Blekinge class boats at the Saab Kockums shipyard in Karlskrona. Finalising the design proved to be problematic and FMV were obliged to contribute an additional SEK 5.2 Bn (EUR 460 M) in August 2021 to enable the project to proceed. A keel-laying ceremony for the first unit was subsequently held in June 2022. Current plans envisage the new submarines being delivered in 2027 and 2028, two years later than envisaged back in 2015. Although the new class has not got off to an entirely smooth start, it has provided Saab with the basis to develop a series of export designs, leaving it as a strong contender for the Dutch Walrus class replacement. Saab is also reportedly working on a ‘U-båt 2030’ concept to meet the need for an eventual replacement of the A19 design. The Swedish Navy reportedly hope to secure agreement to increase submarine numbers to a total of six boats by the 2030s, opening up the prospect of an extended production run.

Given the considerable effort being expended on re-equipping the submarine flotilla, current surface combatant programmes are largely focused on modernisation rather than construction of new ships. The mid-life modernisation of the navy’s two Gävle class corvettes was completed with the return of HSwMS Sundsvall to the fleet in December 2022 after four years refurbishment at Karlskrona. This has allowed attention to turn to similar plans for the five-strong Visby class. FMV contracted Saab to commence project definition for the upgrade in early 2021. However, physical work has yet to commence.

Overall objectives are to bring existing systems to the latest standard and add an anti-air warfare capability, which is currently lacking from the class. Project definition work is also underway on a follow-on YSF 2030 programme that will eventually lead to orders for four new larger surface combatants, two of which should be delivered before the end of the decade. The planned new vessels have been referred to as ‘Visby Generation 2’ corvettes. The intention is that they should make considerable use of the technology adopted for their predecessors’ mid-life modernisation. However, recent press speculation suggests that much larger, frigate-like ships equipped for an area air-defence role are now being considered. In similar fashion to Finland’s aspirations for their new Pohjanmaa class, it is hoped that the vessels will provide an enhanced capacity to contribute to future NATO maritime operations.

Credit: Saab Kockums/YPS Peter Neumann

The approach being taken to modernising the navy’s surface combatants is also reflected in that being adopted for the rest of the surface fleet. In the short-term, the effectiveness of the mine countermeasures (MCM) force will be assured by implementation of a life extension for the five existing members of the Koster class. This will ultimately be followed by acquisition of new MCM vessels a decade or more from now. In December 2022, Saab announced that it had received a SEK 350 M (EUR 31 M) contract to commence work modernising two Koster class vessels. The award also included a SEK 270 M (EUR 24 M) option for the upgrade of the remaining trio.

In the short term, the navy will benefit from the imminent delivery of the intelligence gathering ship HSwMS Artemis. Completion of the vessel was delayed by financial problems at the Polish shipyard that was sub-contracted to build the hull, requiring Saab’s intervention. However, sea trials finally commenced in November 2022. Longer term projects include at least one new logistic support ship, as well as replacements for the renowned CB-90 series of assault craft. It also seems likely that dissatisfaction with the performance of the air force’s maritime-roled NH-90 helicopters will result in their premature retirement. If so, Sikorsky’s MH-60R Seahawk seems to be the most likely replacement.

Credit: Saab AB

Norway

Just as is the case for Sweden, Norway’s current naval procurement is driven by the need to renew its submarine flotilla. The replacement of the Royal Norwegian Navy’s existing six Type 210 Ula class submarines is being taken forward in conjunction with the German Navy under a EUR 5.5 Bn contract signed with tkMS in July 2021. The programme envisages the construction of six boats – four for Norway and an initial two for Germany – to a Type 212CD (Common Design) iteration of the existing Type 212A class. Work on the lead submarine, which is allocated to Norway, is anticipated to commence in 2023 prior to launch in 2027 and delivery in 2029. With subsequent deliveries extending into the middle of the 2030s, the Type 212CD programme will inevitably dominate Norway’s naval acquisition spending for the foreseeable future. Although all the boats will be constructed in Germany, the acquisition will still be of significant benefit to Norwegian industry. Notably, Kongsberg has been contracted to provide a number of sonar systems for the new submarines and is developing their combat management system through the kta naval systems joint venture with Atlas Elektronik. Additionally, Germany has agreed to adopt Kongsberg’s Naval Strike Missile as part of the broader industrial framework support in the deal.

Credit: Forsvaret/Thomas Haraldsen

Turning to Norway’s surface fleet, the most immediate priority is the mid-life upgrade of the six Skjold class fast attack craft, referred to locally as coastal corvettes. In September 2020, Umoe Mandal (the class’s builders) and Kongsberg announced that they would work in partnership to implement the project. Subsequently, in June 2022, Kongsberg announced that the Norwegian Defence Materiel Agency had awarded it a NOK 267 M (EUR 23 M) contract to upgrade the vessels’ combat system. Once completed, the upgrade should allow the corvettes to serve well into the 2030s.

In the medium term, Norway will also need to make a decision on the future of its remaining quartet of Fridtjof Nansen class frigates (a fifth ship, KNM Helge Ingstad, was declared a constructive total loss after a collision and beaching in 2018). Although it appears a limited programme of ongoing improvement is planned, there has been speculation that the Royal Norwegian Navy is concerned about the class’s suitability for extensive modernisation given the demanding nature of their primary operating theatre close to Russian’s ‘bastion’ in the High North. Any replacement would need to be a ‘high end’ ASW vessel, most likely based on an existing allied design. Participation in the British Type 26 or US Navy Constellation (FFG-62) class programmes would appear to offer potential routes forward. Interestingly, Umoe Mandal already provides parts of the superstructure for the Type 26 design.

Norway is also in the course of acquiring new naval aviation assets that will further enhance its overall ASW potential. Notably, the government’s June 2022 decision to terminate its acquisition of the NH90 helicopter and seek reimbursement of the NOK 5 Bn paid under the contract resulted in an urgent need to acquire a replacement shipboard rotorcraft. In March 2023, it was announced that six MH-60R Seahawk would be purchased from Lockheed Martin to fill the gap at a cost of NOK 12 Bn (EUR 1 Bn). Deliveries are scheduled for between 2025 and 2027. Training Norwegian air crew on the new helicopters will be facilitated by fellow Scandinavian NATO partner Denmark, which has operated the MH-60R since 2016. The Royal Norwegian Air Force has already taken possession of five Boeing P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft under a contract valued at approximately NOK 10 Bn (EUR 860 M) that was signed in November 2017. They were all delivered between 2021 and 2022 and will replace the country’s existing inventory of P-3 Orion and DA-20 Falcon types.

Denmark

Of all the Scandinavian countries considered in this report, Denmark’s future naval procurement plans are the least advanced. However, it appears that a major new phase of investment in surface warships is imminent. In August 2022, the Danish Ministry of Defence stated that an investment of up to DKK 40 Bn (EUR 5.4 Bn) was envisaged in the years ahead as part of an announcement launching a new national partnership in the maritime sector. Stating that “Denmark must be capable of building its own warships”, the announcement laid out aspirations to rebuild the skills to design, construct and maintain the new fleet. The partnership follows a public-private sector model encompassing representatives from government agencies, industry, finance and the trade unions.

Credit: Forsvaret/Maria Selnes

Further clarity on the likely shape of the new construction programme is likely to emerge after conclusion of political negotiations to replace Denmark’s current 2018-2023 Defence Agreement. Recent ministerial statements suggest that security in the Arctic and North Atlantic are likely to be key areas of focus in the replacement document. This inevitably bolsters expectations for a renewed phase of significant naval investment. A likely priority is the replacement of the existing four Thetis class patrol frigates. Optimised for deployments in Danish waters around Greenland and the Faroe Islands, these vessels first entered service in the early 1990s. Accordingly, they are now approaching life-expiry.

Recent press speculation suggest that they will be replaced by a new frigate class, probably on a like-for-like numerical basis. Any programme will likely require considerable investment in industrial infrastructure given the 2012 closure of the giant Odense Steel Shipyard that assembled the previous Absalon and Iver Huitfeldt classes. In the meantime, the two Absalon class frigates are to receive upgrades to their ASW capabilities under a programme that is expected to be concluded in 2026.

Credit: Forsvaret/Stian Lysberg Solum

Conclusion

This brief overview of Scandinavian naval procurement highlights the considerable efforts that are being made to rebuild the region’s maritime capabilities after a considerable period of post-Cold War neglect. However, it is clear that this endeavour will not be a straightforward one. Many of the programmes discussed date from many years before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. However, it is unlikely to be much before the end of the current decade before the capabilities that they promise will be delivered. The further enhancements that have been driven by the more recent decline in East-West relations are even further away on the horizon. A notable feature of current programmes is the extent of the challenge posed by the need to rebuild the naval industrial base. The situation is a further illustration of the difficulties of regaining lost capacity once it has been abandoned.

Conrad Waters