The rotorcraft designs of 2030–35 will emerge from the US Future Vertical Lift (FVL) programmes, the NATO Next-Generation Rotorcraft Capability (NGRC), and the European Next-Generation Rotorcraft Technologies (ENGRT). Yet many legacy rotorcraft will fly into the 2060s, putting a premium on upgrades.

Unmanned rotorcraft, using autonomous flight capabilities, are potentially transformative. New sources – China, the Republic of Korea and Turkey among others – have spent years creating a design and production capability. Commercial technologies – including electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) – are being adapted to military manned and unmanned rotorcraft.

FVL: clean sheet designs and cancellations

The US Army’s FVL programme consists of five next-generation rotorcraft designs, each defined by a ‘capability set’ (rather than requirements), providing scope for innovation. The Future Attack and Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) programme, launched in 2018, represented FVL Capability Set 1, an armed scout helicopter to replace the Bell OH-58D Kiowa Warrior, retired in 2014. Previously, three Kiowa Warrior replacements have been cancelled by the Army: the stealthy Boeing-Sikorsky RAH-66 Comanche, cancelled in 2004 (after some USD 7 billion had been spent on the programme), the Bell ARH-70 Arapahoe, cancelled in 2008; and the Armed Aerial Scout programme for an off-the-shelf design, cancelled in 2013.

FARA was the manned armed reconnaissance helicopter the Army said it wanted in 2018, turning away from a previous decision to rely on UAVs and Boeing AH-64E Apache attack helicopters. Studies had projected that, even with advances in autonomous flight and artificial intelligence (AI) technology expected by 2030, armed reconnaissance would still require crews.

Credit: Bell

In February 2024, it was announced that FARA would be cancelled at the end of fiscal year (FY) 2024, as had its three predecessors (four if the Kiowa Warrior upgrade programme that was to be carried out at the Corpus Christi Army Depot is counted). This occurred before the milestone B decision for it to enter the engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) phase or the selection of one of two competing designs: the Bell 360 Invictus, a winged helicopter incorporating commercial sector technologies, and the Sikorsky Raider X2, a compound helicopter powered by two coaxial rotors and a pusher propeller. The two designs were to have had their delayed first flights in late 2024, reflecting issues with their General Electric Aviation T901 engines, developed by the Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP), in which the Army has invested some USD 1.5 billion. After the cancellation, Sikorsky announced that its design would continue development, potentially for international customers.

FARA cost the Army USD 2.4 billion and over USD 1 billion from industry. The cancellation, after repeated assurances (then-Chief of Staff Gen James McConville had affirmed “we are committed” in April 2023) has the potential to deter future industry investment, especially from smaller, innovative firms. The cancellation reflected cutting the FY 2025 budget request in line with the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act. Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth, testifying before a House of Representatives Appropriations committee hearing on 28 March 2023, had identified FARA as being among a number of vulnerable programmes. However, Gen James Rainey, commanding Army Futures Command, said on 8 February in Washington, that FARA should not be characterised “as a failure”.

“We are learning from the battlefield, especially Ukraine, that aerial reconnaissance has fundamentally changed,” US Army Chief of Staff Gen Randy George said in a statement on 8 February 2024. Douglas Bush, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology told a House Armed Services Committee (HASC) hearing on 6 March 2024 that “maintaining the work force and supplier base”, was second only to combat lessons in motivating the Army’s decision. The Army’s classified Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) study for FARA, completed at the end of 2023, compared potential force structures and scenarios. Commenting on the AoA, Congressman Rob Wittman said, “I’m somewhat bewildered on why the Army didn’t factor in a healthier contingency of alternatives.”

Credit: US Army/Luke J Allen

Despite having also been identified by Secretary Wormuth as vulnerable, the Army remains committed to the Future Long Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA; pronounced ‘Flora’). Representing FVL capability set 3, the FLRAA is intended to replace Army Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, although not on a one-for-one basis. The twin Rolls-Royce AE 1107F-powered Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor was selected as the FLRAA in December 2022. Bell is expected to deliver a prototype aircraft in 2025, with the first unit equipped (FUE) in 2030. The initial FLRAA request for information provided to industry called for 4,520 km (2,440 NM) unrefuelled flight range, cruise speed of at least 518 km/h (280 kn), manufacturing unit cost under USD 43 million (FY 2018 dollars), 12 passengers and a 4,540 kg (10,000 lb) slung payload. Yet despite this level of performance, “manned aircraft on the modern battlefield are at extremely high risk”, Gen Rainey said on 6 March 2024.

US legacy systems: Black Hawk, Chinook and the T901 engine

The Army decided to invest aviation dollars in legacy helicopters, keeping Black Hawk and Boeing CH-47F Block II Chinook lines open throughout the 2020s and maintaining their operational viability into the 2060s.

In February 2024, the Army announced it would halt procurement of the Northrop Grumman UH-60V programme at the end of FY 2024. This upgraded National Guard UH-60A/Ls with UH-60M compatible digital cockpits and advanced avionics, including introducing an open systems architecture. The first unit was equipped with UH-60Vs in 2021. The cancellation reflected unit cost growth.

The Army plans to initiate a multiyear procurement of up to 255 UH-60Ms over FYs 2027–32, at an initial rate of 20–25 per year, while the current fleet of some 2,300 Black Hawks will be reduced with the progressive retirement of UH-60A and L models. The Army is funding research and development for upgrades to the Black Hawk. “We hope that that R&D, cutting across the whole FYDP [Future Years Defense Plan], will allow us to have a better Black Hawk,” Douglas Bush said on 6 March 2024. It is uncertain how upgrades will be incorporated into multiyear production or what effect this might have on unit costs.

In February 2024, the Army announced that its CH-47F Chinooks, currently in the Block I configuration, will be upgraded to Block II standard, with a strengthened airframe and drive train (including the incorporation of new Ferrium C61 lightweight alloy components in the drive shaft) and upgraded fuel (single-cell composite tanks) and electrical systems. While Chinook reengining is not part of current planning, Block II can accommodate heavier and more powerful engines. It has been tested with the GE Aviation T408, an uprated Honeywell T55 and the Honeywell HTS7500. The Advanced Chinook Rotor Blade (ACRB), previously considered for integration in Block II, was deferred in 2022 after encountering problems in testing. The first six production Block II upgrades were included in the USD 700 million requested for the programme in the FY 2025 budget.

Previously – in 2018, and, again, in 2023 – rather than requesting funding for upgrading its CH-47Fs to Block II standard, the Army had expressed satisfaction with operating Block Is, limiting Block II upgrades to MH-47G Chinooks operated by Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and international sales. The decision announced in February reversed the previous planning. The Chinook, alongside the Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion, is currently entering full-rate production for the US Marine Corps (19 requested in the FY 2025 budget) and Israel. Preparing for its first operational deployment, now postponed to 2026, will dominate the manned heavy lift rotorcraft market for the near future, although the Army’s Uncrewed Heavy Lift study has looked at applying emerging technologies to a UAV.

Credit: Boeing

On 6 March 2024, Congressman Donald Norcross said that expanding the Block II programme, “mitigates emerging risks in the Philadelphia area industrial base” and stressed “stability in the industrial base matters”. While not cited as a reason, 2024 is a presidential election year. Pennsylvania – where the Chinook is built – is one of only six or seven states that, in the US’s polarised politics, is considered capable of voting for either candidate.

Currently undergoing ground testing, the T901 is a form-fitting 3,000 shaft horsepower (shp) turboshaft engine with the same volume and weight as current engines but with greater power, fuel efficiency, reliability and sustainability, providing a margin for further power growth. Designed for full authority digital engine control (FADEC), the T901 enables potential autonomous and unmanned flight that could make use of innovative technologies.

The February 2024 announcement delayed the T901’s transition from development to production for two years, “to ensure adequate time to integrate it with AH-64 and UH-60 platforms” according to the Army press release – but continued to plan to reengine its Apache and Black Hawk fleets, with Maj. Gen Michael ‘Mac’ McCurry, commanding general of the Army’s aviation schoolhouse, speaking in Washington on 10 October 2023, expressed his support for the T901 programme, with “a great PEO [Brig. Gen David Phillips, Program Executive Officer for Aviation] and partnership with the OEM [original equipment manufacturer]”. Brig. Gen Phillips, speaking on 6 March 2024, identified the T901 as a potential source for engine upgrades, “lots of great technology in that engine”.

In addition to reengining, Boeing AH-64E Apache programme includes rotor blade and drive train updates and standardising the fleet, starting in FY 2026, as Version 6.5, including new software. An open systems interface (OSI) will be introduced as a step towards an open system architecture. The Northrop Grumman AN/APR-39E(V)2 has entered production as an upgraded radar warning receiver (RWR). The Apache will remain in production for the US Army until 2027 and will be in service into the 2050s. The proliferation of loitering munitions and attack UAVs and perception of the vulnerability of manned aircraft over the battlefield may lead to additional upgrades, including integration of systems developed for FARA.

Crossing the Valley of Death? SPRINT and ANCILLARY

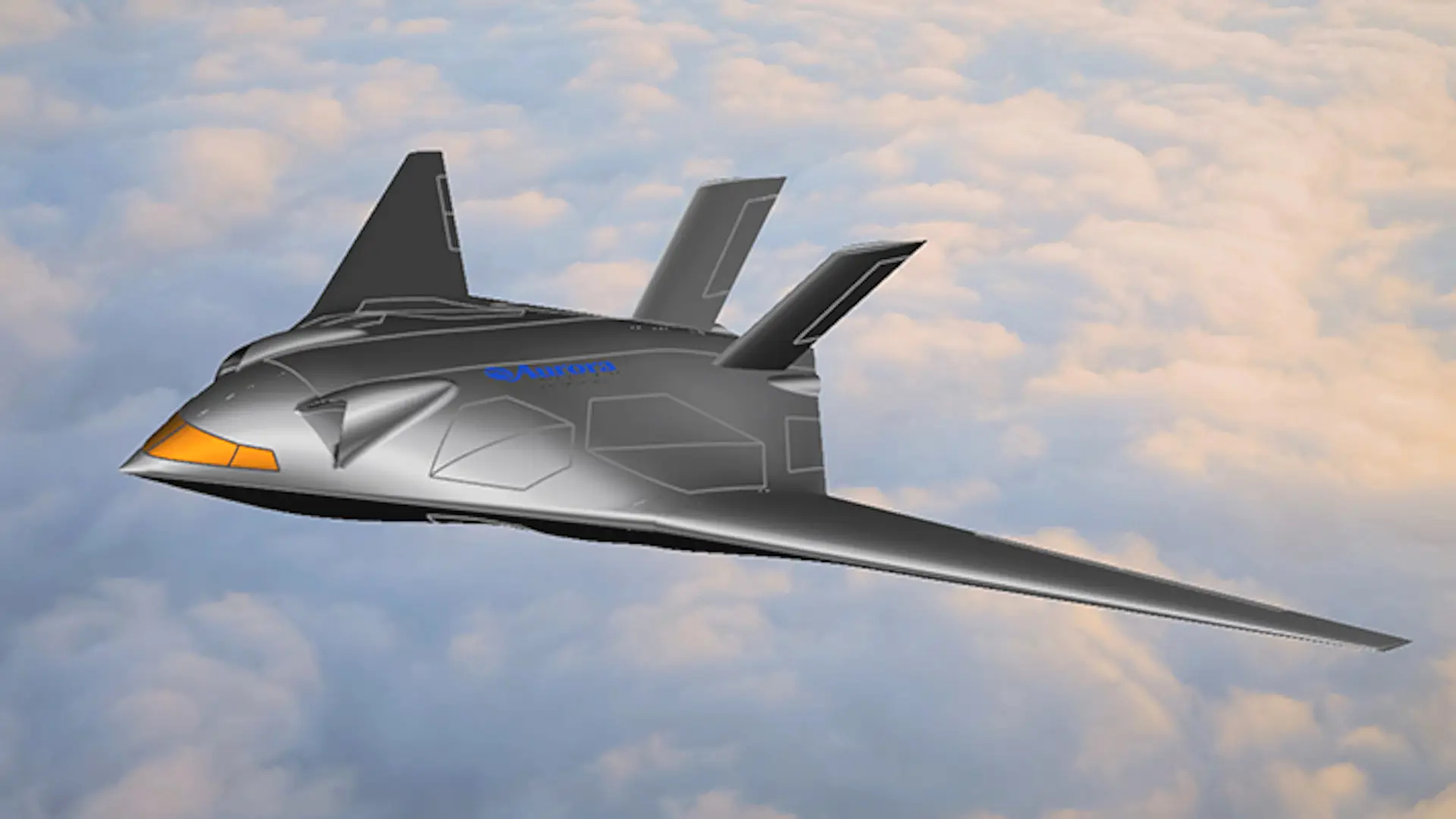

The SPRINT (Speed and Runway Independent) is a US Defense Advanced Research Programs Administration (DARPA) programme to provide SOCOM’s Highspeed VTOL (HVTOL), cruising at 741–833 km/h (400–450 kn) and replacing Air Force Special Operations Command’s (AFSOC) Bell-Boeing CV-22 Osprey tiltrotor. Contracts were awarded by DARPA in November 2023 to Boeing’s Aurora subsidiary, Bell, Northrop Grumman, and Piasecki Aircraft to refine proposed SPRINT designs.

Credit: Aurora Flight Sciences

Involving industry early in the programme and working with SOCOM – with a record of making things happen – DARPA is looking to get SPRINT – in the 2030s – across the ‘valley of death’: the disconnects that have prevented many DARPA programmes leading to production.

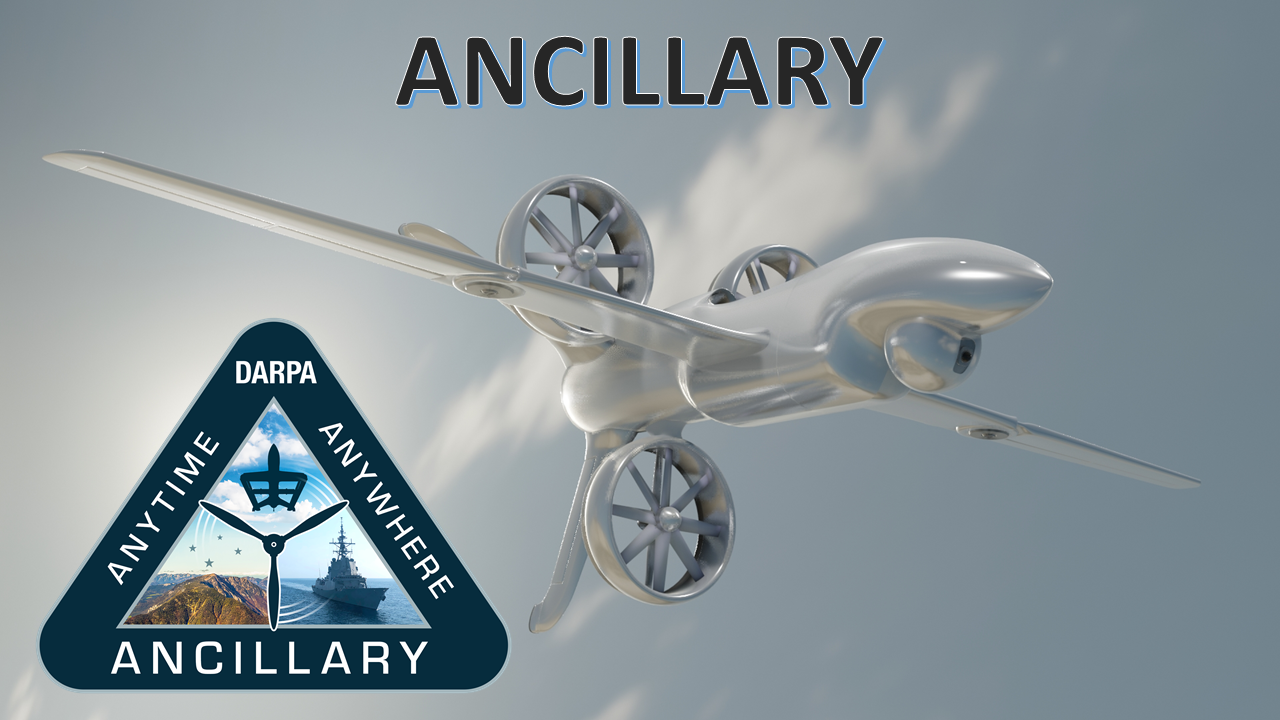

SPRINT is following DARPA’s The AdvaNced airCraft Infrastructure-Less Launch and Recovery (ANCILLARY) programme for low-weight, large-payload, long-endurance VTOL. Aiming to demonstrate experimental VTOL UAVs able to operate without launchers or ground or shipboard infrastructure by 2026, in June 2023, DARPA issued contracts for designs to AeroVironment, AVX Aircraft, Griffon Aerospace, Karem Aircraft, Leidos, Method Aeronautics, Northrop Grumman, Piasecki Aircraft and Sikorsky. DARPA will decide in 2024, which of these are to be funded to fly experimental aircraft. ANCILLARY is looking to provide technologies for US Navy and Marine Corps near-term requirements.

Credit: DARPA

NATO & EU: upgrades and new designs

The NATO Next Generation Rotorcraft Capability (NGRC) programme, launched in November 2020 by France, Germany, Greece, Italy, and the UK (as lead nation), has since been joined by The Netherlands and, in 2023, Canada, with the US and Spain as observers. The programme intends to replace some 1,000 helicopters, such as the NH Industries NH90, Airbus Helicopters H225 Super Puma and Leonardo AW101 Merlin. Following an initial pair of concept studies on on-board systems requirements, in February 2024, the NATO Support & Procurement Agency (NSPA) – managing the NGRC programme – asked for bids from three prime contractors to each develop one or two “Candidate Integrated Platform Concept(s)”. A team from Bell and Leonardo has offered a tiltrotor design concept, while Sikorsky has offered a compound helicopter design. The concept phase of the programme will run until 2025, followed by development and production, achieving initial operating capability (IOC) by 2035.

The required performance – difficult to achieve with a conventional helicopter configuration – is to cruise at 333–407 km/h (180–220 kn), have a range of over 1,650 km (900 NM), an endurance of over five hours (or eight with additional tanks), transport 12–16 passengers, have a maximum take-off weight of 10–17 tonnes, a unit cost under EUR 35 million (USD 41.3 million) and cost under EUR 10,000 (CY 2021) per flight hour (half the cost Sweden experienced operating NH90s). Electric or hybrid power are potential downstream additions.

A counterpart effort announced on 23 May 2023, the Next Generation Military Helicopter (NGMH) is a cooperative programme of the European Union’s Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), including France (lead), Italy, Finland, and Sweden. Its objective in the near term is to upgrade existing rotorcraft – likely prioritising the NH90 – and then to use emerging technologies to achieve fieldable solutions, either through upgrades or new designs by 2040 that, in the words of the announcement “include the ability to face high intensity conflicts”. It will run concurrently with the EU’s European Next-Generation Rotorcraft Technologies (ENGRT) programme, announced in late 2022, to identify candidate technologies for the NGMH. The ENGRT programme brings together Airbus and Leonardo, Europe’s two main rotorcraft manufacturers, along with over 20 other industrial participants. In 2023, France’s Safran and Germany’s MTU Aero Engines agreed on a joint venture to develop powerplants applicable to the programme.

Near term: NMH

In 2025, a contract will be awarded for the RAF’s requirement for the twin-engine New Medium Helicopter (NMH), replacing 23 Airbus Helicopters Puma HC2 helicopters with 36–44 new helicopters, to be delivered in 2027–28 for between GBP 900 million (USD 1.03 billion) and GBP 1.2 billion (USD 1.4 billion). An existing design will be selected from one of three OEMs: Airbus (H175M), Leonardo Helicopters UK (AW149), and Lockheed Martin UK (S-70M Black Hawk).

Credit: US Navy/Spc 3rd Class Drew Verbi

For other rotorcraft needs, the UK Rotorcraft Concepts and Tactical Aviation Research programme, announced in 2022, is looking at the range of options available for 2030–40, likely to be dominated by rotorcraft resulting from the FVL and NGRC programmes.

Emerging technologies

A broad range of technologies have the potential to enable revolutionary changes in rotorcraft. In recent years, rotorcraft such as the earlier Airbus Helicopter X3 technology demonstrator, the Airbus Rapid and Cost-Efficient Rotorcraft (RACER) and the Leonardo AW609 tiltrotor – the latter to be demonstrated to the Italian military – have pointed towards future military application. The rotor system on Bell’s FARA design was based on that developed for its 525 Relentless, which has been tested at over 370 km/h (200 kn) true airspeed. “Commercial technology is moving much quicker than military technology in a lot of areas,” Gen George said in Washington on 7 March 2024. Rotorcraft has the potential to be among them.

In the US, with FARA cancelled and FLRAA moving towards production, new technologies will emerge from the civil sector or from programmes such as the Navy’s FVL (Maritime Strike). It will include capabilities for multiple shipboard missions by both manned and unmanned aircraft. The FVL (MS) AoA was completed in 2023. The Marine Corps, rather than looking towards replacements, is developing a family of VTOL designs that, like FVL (MS), will likely include UAVs and optionally-manned rotorcraft.

Innovation will be enabled through international cooperation, exemplified by the March 2024 agreement between Bell and Leonardo on tiltrotor technology and the participation of international observers – including the UK – in the FVL programme.

“We have to get better at rapidly adopting technology that already exists”, Gen Rainey said on 6 March 2024. Unmanned and autonomous capabilities are one area where future designs are likely to take advantage of advanced technologies. A “Cambrian explosion of autonomous systems” is already underway, Gen Sir Patrick Sanders, the UK’s Chief of the General Staff, stated in Washington DC on 11 March 2024.

Advances in manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T), AI, autonomous and pilot-optional flight are already in service; the US Army has demonstrated controlling UAVs from Apaches for example. Degraded visual environment (DVE) capability is in service on manned helicopters, currently SOCOM Black Hawks. This capability, in the future, is “definitely going forward, so we can put Rangers on an objective when no one else can fly”, Maj. Gen McCurry said on 6 March 2024.

Credit: Leonardo

The modular open systems architecture (MOSA), integral to the design of FVL and NGRC rotorcraft, is intended to make system upgrades easier and less costly, enabling a ‘plug and play’ capability. MOSAs may also upgrade legacy systems. The US Army will fund research and development for a Black Hawk MOSA, which Maj Gen McCurry identified as a top priority. “The ability for us to turn and be more nimble as we react to changes on the battlefield and put a new piece of kit on a Black Hawk, that open architecture helps us do that very well,” he said on 6 March 2024.

Predictive maintenance capabilities and advanced sustainable structures minimise maintenance and reduce sustainment costs. These have been in service for years, especially on commercial helicopters, but are adapted for military use, most notably on the Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion, which uses a system developed from those on the S-92 and the earlier CH-53E.

Other emerging technologies include shape-shifting main rotor blades such as those developed by DARPA’s Mission Adaptive Rotor (MAR) programme. While the turboshaft will continue to dominate manned rotorcraft power, hybrid or full electric powerplants will be increasingly used for UAVs and offer reduced acoustic and infrared signatures. The Air Force’s Agility Prime programme, announced in April 2020, is using commercial-sector technology to accelerate optionally piloted, remotely piloted and autonomous VTOL. Multiple electric VTOL designs have been evaluated and more will follow in 2025. In 2023, sustainable aircraft fuel (SAF) was used for a test flight, powering one of the two Safran RTM322 turboshafts of an NH90. Digital engineering has created improved engines and enabled the design of supporting systems such as ‘digital twins’ for testing planned improvements and virtual reality maintenance simulators. New engine materials, lighter and cheaper, enable higher temperatures and greater reliability, combined with 3D printing fabrication technologies that have reduced parts counts.

High-performance rotorcraft – with FLRAA, NGRC and SPRINT as examples – will start to transform military fleets in the 2030s. By then, upgrades, VTOL UAVs and autonomous flight capabilities are likely to see progress, and new countries will be supplying rotorcraft on the international market, transforming it in much the same way as happened with the proliferation of UAVs and loitering munitions, as witnessed in recent conflicts. As the FARA cancellation has shown, gaining the benefit of emerging technologies at a time when legacy helicopters must be upgraded to remain operationally viable is already proving to be a challenge.

David Isby