Nascent UK satellite service provider Methera is approaching the market with a unique two-strand strategy designed to establish itself as a key player in the global space domain.

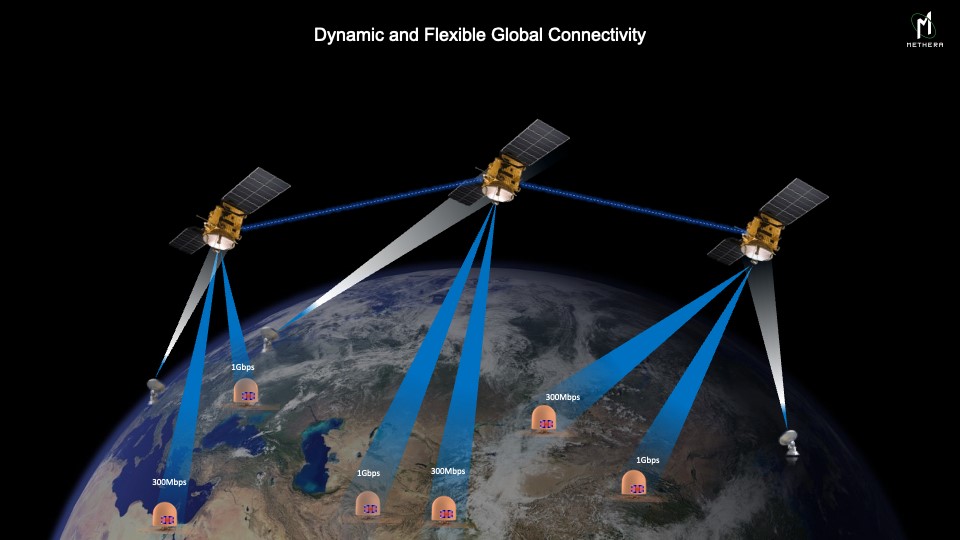

Central to this strategy are Methera’s plans to establish a constellation of satellites in medium Earth orbit (MEO) at an altitude of 20,000 km that will perform two key missions. Firstly, they will offer focused, high-capacity, ultrafast broadband to specific locations on Earth that need it, such as for ongoing military operations, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief or to population centres that currently lack such a capability. Secondly, they will carry sensors to facilitate space domain awareness (SDA) focused on the protection of critical space assets, especially in relation to actions by potentially hostile manoeuvring space vehicles that cannot easily be tracked by Earth-based observation systems.

In addition to these two key missions, Methera will also offer the ability to carry hosted payloads to further optimise the economic viability of its operations and is currently working to define the required specifications that will facilitate this.

Methera will initially launch up to 12 satellites in two orbits to serve any spot on the Earth 24/7, but has filed with the International Telecommunications Union to establish up to 128 satellites on four different orbits.

Thus far, Methera has designed the whole system, built the tasking platform to control the satellites, put out design requests for proposals to the major satellite builders and has scheduled the launch of its first satellite. Funding for this first satellite, which will effectively be Methera’s ‘flag in the sand’ of the space domain and be launched using a SpaceX launch vehicle, is close to being secured.

Speaking to ESD in London on 7 March 2025, Methera CEO Chris McIntosh explained the rationale behind the company’s strategy.

With regard to providing high-capacity broadband services, McIntosh noted that broadband providers using satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) do not realistically have the ability to deal with transitional, high-capacity requirements in specific locations.

“Everyone’s trying to put more and more broadband around the Earth, whether it’s OneWeb, StarLink or ViaSat, continually increasing the amount that is delivered to customers,” he said. “But that just doesn’t make sense because the maths doesn’t work. At some point, if you can only increase services by growing entire constellations across the whole globe, you will never be able to deal with the peaks, the areas where the demand is significantly more than the average, without leaving hundreds, if not thousands, of under-utilised satellites elsewhere.

“What we’re doing is the opposite,” McIntosh explained. “From our satellites we will be able to deliver broadband to any point on the Earth from multiple satellites, providing an immense amount of capacity into targeted regions. So our aim is to complement what the other suppliers are trying to do – meet the ever growing demand for satellite broadband – but focused on the areas where demand outstrips availability.”

Noting that LEO-based satellite broadband providers are all over-subscribed in certain areas, but only for certain times, McIntosh said, “That’s the key thing: realise right from the start that, [regarding] our end users, we might have them for months, we might have them for a small number of years. The normal satellite-based model is ‘Grab a customer, hold on to them for 10 years’, and that’s how they balance their books. What we’re saying is, ‘Build a system that’s flexible enough that you can have someone for three months and you’re not losing out because, although the end user will change, your customer, who’s paid for the beam for a number of years, doesn’t change.”

A typical customer example McIntosh noted would be for a military operation where armed forces deploy into theatre using military satellite communications (satcoms) but then want to transition to a commercial provider as soon as practicable to preserve their ‘hardened’ military bandwidth.

“At that point, where the military is trying to purchase commercial bandwidth, it costs an absolute fortune because everybody is after it – the press, news gatherers want it; all the different agencies want it – so all of a sudden they’re trying to buy bandwidth at the point where it’s most expensive.

“Our start point was that we wanted to provide complementary bandwidth to any spot on the Earth and to move these spots in real time to where they were needed,” said McIntosh, referring to rural regions and areas on the outskirts of towns that were not adequately serviced by either fibre- or other satellite-provided broadband. “That then moved to not just the outskirts of towns, etc, but the users who need temporary bandwidth, like the military, large areas of the government, [and for] cable restoration organisations” where Methera would bridge the gap by delivering ‘fibre in the sky’ connectivity.

With this plan laid out, Methera then approached the UK Space Agency to point out that, with its constellation of MEO satellites orbiting at 20,000 km, it was in a prime position to also offer an additional SDA capability.

McIntosh noted that, while Earth-based sensors can proficiently track satellites while they are doing no more than simply remaining in their respective orbits, as soon as they start manoeuvring – ie actually flying through space – those Earth-based sensors can then spend months trying to relocate them.

“The reason why that’s critical is that the Methera satellites will be ideally positioned to collect unique data and information on the movements and intentions of man-made space objects and natural obstacles such as space debris. What we’re looking at is what potential adversaries’ satellites are doing in interfering, interrupting, some of the very expensive and crucial military and government satellites,” said McIntosh. He further explained that, while the Western allies have been increasingly building more ground-based sensors to address this problem, because of the Sun’s position in relation to these sensors there are large areas of space that cannot be observed at a given time: a situation that potential adversaries readily exploit.

Most high-value satellites orbit in geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) at an altitude of around 36,000 km, so trying to observe what is going on there is little improved by placing sensors on LEO satellites, which are only 500 km above the Earth.

Methera’s satellites, however, would be at 20,000 km. “Now we’re more than halfway to GEO,” McIntosh explained, “so we’ve significantly reduced the distance between our sensors and the target areas. What’s key is, out at 20,000 km, we’ve got satellites on four different orbits, and that means that we can look from multiple angles at the targets. And then, of course, because our satellites are slow movers, you’ve then got the long stare where you’re looking at that same target for a long period of time, which allows you to see different aspects of it and get different information and intelligence from it.”

Methera’s MEO constellation, McIntosh asserted, would at least halve the solar exclusion zone where a target cannot be observed from the Earth or from a LEO-based satellite. While the Methera satellites would not have the ability to get close to a suspect satellite, they would, said McIntosh, provide a ‘queuing and tipping system’ to other organisations.

Methera has received GBP 6 million (EUR 7.17 million) grant from the UK Space Agency to demonstrate this and other MEO-based capabilities.

Lastly, McIntosh noted that “what we see from this whole queuing and tipping piece has, of course, a military angle, but there will also be a future space traffic control requirement. It’s only a matter of time before one starts to emerge because, with launches going up through LEO, to GEO and beyond, whether to the Moon or Mars, and the number of satellites in space increasing rapidly, traffic management is quickly becoming an issue. Soon spacecraft will be managed in a similar fashion to aircraft; there will have to be some form of space traffic control, and we believe that the Methera system will form a key component of it.”