The six members of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – currently supply around 20% of the world’s total oil output. When the output from Iran and Iraq is added, this takes the total to around 30%. This major natural resource can make countries in the region tempting targets for aggression, as was demonstrated by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990.

To cope with the threat of air attacks upon their cities or critical assets, or enemy air operations in support of hostile ground forces, the GCC nations have invested heavily in air defence. This capability takes the form of interceptor or multi-role fighters, supplemented by surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems, and point-defence SAMs including man-portable air-defence systems (MANPADS). In most cases, the result is a multi-tier system intended to cope with low, medium and high altitude threats, or even incoming ballistic missiles.

While it is easy to document many of the modern weapon systems deployed in the region, especially hardware supplied by the United States, information sources such as reference publications can show a measure of disagreement over exactly which systems are in service with each country. The situation is made even more complicated by the presence of ageing and obsolescent hardware that may no longer be in front-line service, yet could be in storage and potentially available for use.

Saudi Arabia

Four of the six GCC states now operate the Raytheon MIM-104 PATRIOT, while three have taken the concept of missile defence a stage further by adopting the Lockheed Martin Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system. The first PATRIOT user in the region was Saudi Arabia, which became the fifth export customer for the system in 1990 when it ordered seven PATRIOT fire units, 48 launchers, six MPQ-53 radars, six engagement control centres, and 384 PAC-2 missiles. Further deliveries then took place under a USD 1.03 Bn contract placed in December 1992. A contract in June 2011 upgraded Saudi Arabia’s PAC-2 systems to the Config-3 standard, which made them compatible with the PAC-3 missile. A batch of 202 PAC-3 missiles, 36 launching station modification kits, and six fire-solution computers was requested in September 2014.

Faced with drone and missile attacks from the Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen, in 2021 Saudi Arabia requested the supply of more PATRIOT missiles. A batch of 300 PATRIOT MIM-104E Guidance Enhanced Missile-Tactical ballistic missile (GEM-T) missiles, and items of PATRIOT support equipment form part of a planned sale announced in August 2022. Intended to replenish Saudi Arabia’s stock of PATRIOT missiles, “these missiles are used to defend the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s borders against persistent Houthi cross-border unmanned aerial system and ballistic missile attacks on civilian sites and critical infrastructure in Saudi Arabia,” the US Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) stated.

The US approved the potential sale of THAAD missile defence systems to Saudi Arabia in May 2018. The Saudi government had requested 16 THAAD Fire Control and Communications Mobile Tactical Station Groups, seven TPY-2 THAAD radars, 44 THAAD launchers, and 360 THAAD missiles, plus support equipment and training. A USD 1.42 Bn contract awarded to Lockheed Martin in March 2022 covered additional interceptors for the US and Saudi Arabia.

Since the 1980s Saudi Arabia has been a major user of the Raytheon MIM-23B I-HAWK medium-range system, deploying a force that peaked at 16 batteries and a total of 126 launchers, operated by the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF). Although 17 nations still operate HAWK, following the decision by Spain to supply Improved HAWK Phase III systems to Ukraine and the announcement of a US programme to refurbish HAWK missiles destined for use with these, there have been claims that the system is totally outdated, and not suitable for modern combat operations. However, at least two websites have that have published such allegations have identified their source as being ‘Russian military experts’.

HAWK entered service in 1959, but has undergone a series of modernisation programmes, first under the HAWK Improvement Program (HIP) begun in 1966, which brought HAWK to the Improved Hawk (I-HAWK) standard, and then again under the US Army Product Improvement Plan (PIP) which received full materiel release in August 1979. PIP Phase I replaced the I-HAWK’s AN/MPQ-48 Continuous Wave Acquisition Radar (CWAR) with the AN/MPQ-55 Improved CWAR, and upgraded the AN/MPQ-50 Pulse Acquisition Radar (PAR) to provide a digital Moving Target Indicator (MTI) capability. Fielded between 1983 and 1986, the Phase II version provided the AN/MPQ-57 High Power Illuminating Radar (HPIR), which replaced some of the vacuum-tube electronics of the AN/MPQ-46 HPIR with modern solid-state hardware, and added an optical Tracking Adjunct System (TAS) intended to allow operation in the face of severe electronic countermeasures. Deployed from 1989 onwards, Phase III involved more extensive changes including the replacement of the AN/MPQ-55 with the AN/MPQ-62 CWAR, and an improved AN/MPQ-61 HPIR incorporating the Low-Altitude Simultaneous Hawk Engagement (LASHE) mode, which uses a wide-angle, low-altitude radar illumination pattern to allow multiple engagements against saturation raids. Saudi systems were originally delivered at the Phase II standard, but in 1995 Saudi Arabia placed an order worth USD 118 M for upgrade kits that would allow Phase II systems to be upgraded to the Phase III standard.

Credit: US Army

For shorter-range air defence, the Saudi Army uses the Thomson-CSF (now Thales) Crotale, and is currently thought to have around 40 fire units. A custom-designed Crotale variant known as ‘Shahine’ is based on a tracked chassis, and is used to protect mobile forces. This exists in two versions – the original Shahine 1 ordered in 1975, and the improved Shahine 2 procured around a decade later. Shahine 1 systems were upgraded to the Shahine 2 standard in the early 1990s. Early in 2001, Saudi Arabia placed a USD 129 M contract with Thales for the modernisation of its Crotale systems delivered in 1985, as well as for the supply of logistics and support services, and began to negotiate a modernisation of the Shahine 2.

The main MANPADS presently in service with the Saudi Army are multiple variants of the Raytheon FIM-92 Stinger family, which is also used on Boeing M1097 Avenger vehicles. Five MBDA VL MICA are reported to be in service with the Saudi Arabia National Guard, along with 68 examples of the Multi Purpose Combat Vehicle (MPCV) armed with the MBDA Mistral 2.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) – a federation of seven emirates, consisting of Abu Dhabi (the capital), Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm Al Quwain – was the first member of the GCC to deploy upper-tier SAM systems able to provide missile-defence capabilities. Abu Dhabi currently deploys a mixture of PATRIOT GEM-T and PAC-3 missiles. A total of nine batteries are reported to be deployed to defend major population centres and critical infrastructure sites.

The UAE was the first foreign purchaser of the THAAD system, placing an order in 2011. It is currently thought to have two operational THAAD batteries, one positioned to defend Abu Dhabi city, and the other to defend the Al-Ruwais area. In January 2022, the system made its first operational intercept of an enemy missile when it intercepted multiple threats directed towards areas in Abu-Dhabi, including Al-Dhafra Air Base. A second successful engagement was reported in the following month. August 2022 saw the announcement of the proposed sale to the UAE of two more THAAD launch control stations, two THAAD tactical operations stations, 96 THAAD missiles, and associated support equipment.

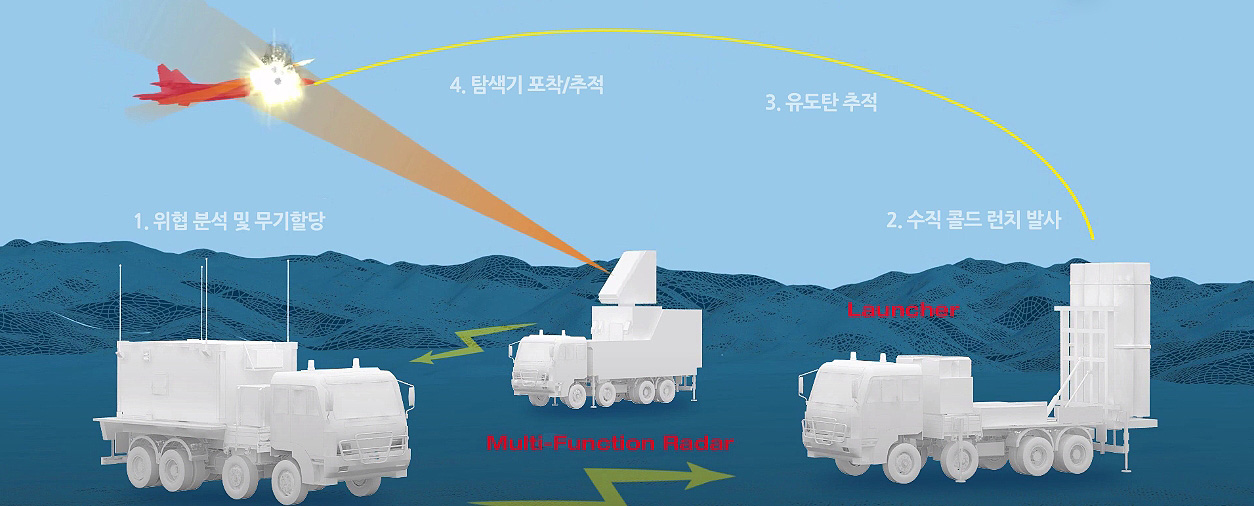

A further expansion of the UAE’s air-defence capability was announced in January 2022 following the signing of a contract by South Korea’s LIG Nex1, Hanwha Systems, Hanwha Defense, and the UAE’s Tawazun Technology and Innovation (TTI) organisation. It covers the procurement of South Korea’s Cheongung II missile system, and is expected to involve a customised version of Hanwha Systems’ multifunction radar (MFR). Development of the Cheongung II began in 2012 with the aim of creating a system able to counter ballistic-missile targets.

Five batteries of I-Hawk are reported to be in service, a mix of Phase II and Phase III systems with a total of 30 launchers. These are supplemented by Bofors RBS 70 MANPADS systems purchased by Dubai in 1979, and by Matra BAe Dynamics (now MBDA) Mistral twin-round ATLAS (Affût Terrestre Léger Anti-Saturation) launchers. The Matra BAe Dynamics Rapier had been in service with Abu Dhabi, but these systems were repurchased by the company under an agreement reached in 1989.

The UAE became the launch customer for the KBP Instrument Design Bureau Pantsir-S1 (SA-22 ‘Greyhound’) when it ordered 50 examples in May 2000. Deliveries of a small number are reported to have begun in 2007, but these showed technical problems which postponed the arrival of the remainder until 2009–2013. The chosen platform was the MAN SX 45 8×8 truck, which makes the UAE systems immediately recognisable. This was demonstrated in mid-2020 when Government of National Accord (GNA) forces in Libya captured a MAN SX 45-based Pantsir thought to be one of a batch that had been in service with of the rival Libyan National Army (LNA).

There are conflicting reports of an upgrade planned for the UAE’s Pantsirs. A USD 12 million contract for an upgrade was announced by the UAE in 2019, but in 2021 Dmitry Shugayev, director of Russia’s Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation announced that Russia and the UAE were discussing a possible upgrading of the Pantsir-S1. It is possible that the latter statement could refer to a proposal to update the UAE systems to the new Pantsir-S1M standard, which introduces an improved tracking radar and a new 57E6M-E high-speed missile that extends the maximum engagement range from the current 20 km to 30 km.

Qatar

The next overseas sale for THAAD came in 2014 when Qatar ordered 12 THAAD launchers, 150 THAAD missiles, two THAAD fire control and communications units, two TPY-2 THAAD radars, and one early-warning radar. By the end of that year Qatar was ready to become the 13th export customer for PATRIOT. The initial contract was reported to include 11 PATRIOT Configuration-3 modernised fire units, 11 MPQ-65 radars, 11 engagement control centres, 30 antenna mast groups, 44 launchers, 768 PATRIOT Advanced Capability 3 (PAC-3) missiles, 246 PATRIOT MIM-104E GEM-T, 10 PAC-3 test missiles, and two PATRIOT MIM-104E GEM-T test missiles. A contract awarded to Raytheon in 2015 covered the procurement, delivery and installation of an Air and Missile Defence Operations Centre, and the integration of this with various air and missile defence systems.

By the end of 2018, at least one PATRIOT system was operational with what was then the recently-formed Qatar Emiri Air Defences Forces (QEADF). It was initially operated with the assistance of US personnel until more trained operators become available.

Qatar procured the National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS) as a direct commercial sale, and in November 2018 the US DSCA announced approval for the sale of 40 AIM-120C-7 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAM) missiles for use with the system, and the supply of classified software for the AN/MPQ-64F1 Sentinel Short Range Air Defence radar.

The main short-range SAM system currently in service is the Roland 2. Ordered in 1986 from what was then Euromissile, the deal was reported to have been for a mix of systems mounted on the AMX-30 chassis, MAN SX90 8×8 chassis, and on shelters. The arrival of these allowed Qatar to phase out its Rapier systems, and transfer these to Oman. Mistral and FIM-92 Stinger are the main MANPADS in current service, supplemented with the Chinese-developed FN-6.

Kuwait

Kuwait was an early adopter of the PATRIOT system in the region. A total of 40 launchers and 210 PAC-2 missiles were purchased in 1993 under a USD 327 M contract. A possible Foreign Military Sale to Kuwait of 209 MIM-104E PATRIOT GEM-T Missiles was reported by the DSCA in 2010, followed by an order announced in 2012 for four PATRIOT radars, four PATRIOT Engagement Control Stations, 20 PATRIOT Launching Stations, two Information Coordination Centrals, and 60 PATRIOT Advanced Capability (PAC-3) missiles. A batch of 84 PATRIOT Advanced Capability Missile Segment Enhancement (PAC-3 MSE) rounds plus related equipment were delivered under a USD 800 M package approved by the US Government in 2020.

The Air Force also operates four batteries of Raytheon Company MIM-23 I-HAWK low- to medium-altitude SAMs. Prior to the 1990 invasion by Iraq, Kuwait had five I-HAWK batteries. Three of these saw combat action, downing a total of 23 Iraqi aircraft and helicopters. The four batteries thought still to be in service are Phase III standard, and have a reported total of 24 launchers.

In 1998 Kuwait purchased five batteries of ‘Amoun’ low-level air-defence systems, and took delivery of five more in mid-1990. This is an Egyptian-manufactured version of the Oerlikon-Contraves Skyguard/Sparrow air-defence system, which combines the Skyguard fire-control system with Oerlikon Contraves (now Rheinmetall Air Defence) twin 35 mm towed anti-aircraft guns and four-round surface-to-air launchers for the Raytheon AIM-7 or Selenia (now MBDA Italy) Aspide missiles. These systems were seized by Iraq, and some of the hardware was returned to Kuwait after the 1991 Gulf war.

In June 2001 Kuwait Defence Minister, Sheikh Jaber al-Mubarak al-Sabah announced that up to five additional Amoun systems would be purchased, enough to equip an air-defence battalion. “We have five [batteries] and we will buy another five,” the minister said. Each Kuwaiti battery consists of one Skyguard, plus two twin-35 mm guns and two Sparrow launchers. More than a decade ago, MBDA began a three-year programme to modernise the Kuwaiti air defence brigade’s existing stock of Aspide missiles to the Aspide 2000 configuration, and to reconfigure the Amoun systems in order to handle the updated missiles.

Credit: Kongsberg

The next SAM system to enter Kuwaiti service is likely to be NASAMS. In October 2022 the US DSCA reported that the State Department had approved a possible Foreign Military Sale to Kuwait of seven MPQ-64FI Sentinel radars, 63 AIM-120C-8 missiles, 63 AMRAAM-Extended Range (AMRAAM-ER) missiles, 63 AIM-9X Sidewinder Block II missiles, and related equipment for an estimated cost of USD 3 Bn.

Prior to the 1990 invasion, Kuwait had 20 Antey 9K33 Osa (SA-8 Gecko) low-altitude surface-to-air missile systems that had been purchased in the late 1980s. Following the 1991 Gulf War, these were taken to Iraq to supplement that nation’s Osa systems, and were never returned.

For point-defence, Kuwait has several types of SAM system. Short Brothers (now Thales Air Defence) Starburst Lightweight Multiple Launchers were purchased under a 1994 contract worth GBP 50 M, which is thought to have covered 48 launchers (some or all of which were fitted with Thermal Imagers intended to give a 24 hour capability) and at least 250 missiles. However, given that these missiles are approaching 30 years in age, their serviceability is questionable. Additionally, Kuwait operates the FIM-92 Stinger family.

Bahrain

In October 2017, Bahrain announced was considering procurement of the Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system, but two years later the US Department of State approved Bahrain’s procurement of 60 PATRIOT PAC-3 MSE missiles, 36 PATRIOT MIM-104E GEM-T missiles, and nine M903 Launching Stations.

Until the debut of PATRIOT, the longest-range SAM system operated by Bahrain had been the Raytheon MIM-23B I-Hawk. Six systems are reported to remain in service, all being the Phase III standard. Ten Crotale units are also reported to be in service.

Point defence is provided by around 40 Saab Bofors Dynamics RBS 70 low-altitude surface-to-air missile systems purchased in 1979, plus the Raytheon FIM-92A Stinger MANPADS. The procurement of 9K338 Igla-S (SA-24 Grinch) has not been confirmed.

Oman

The longest-range SAM system in Omani service is Raytheon’s NASAMS. Designed to engage aircraft, helicopters, cruise missiles, and UAVs, it normally consists of three launchers, each carrying up to six missiles. NASAMS was initially designed to use the AIM-120 AMRAAM, but can use the AIM-9X Sidewinder or other missiles. Crotale NG fills the gap between this shorter-range systems.

In November 2000, Oman became the first country in the Middle East to be equipped with the MBDA Mistral 2, a version with an improved passive infra-red nose mounted seeker, digital processing, a new booster, higher top speed, greater manoeuvrability and increased range. It opted for the vehicle-mounted twin-round ALBI launcher variant, which is mounted on a Panhard Vehicule Blinde Leger (VBL) 4×4 light armoured vehicle. Oman was the first customer for the ALBI system, whose launcher can be fitted with a thermal imager, which allows day and night operation. The procurement also included a number of VBL-mounted MBDA Mistral Coordination Post (MCP) systems. Each can control the fire of several ALBI vehicles.

An initial procurement of 28 BAe Dynamics (now MBDA) Rapier battery fire units between 1974 and 1977 was followed in 1980 by an order for 12 Blindfire radar trackers. This force was supplemented by 12 launchers and six tracker radars received from Qatar. In the early 1990s, Omani systems were rotated back to the UK to be modernised to the SAHAM standard, which is the equivalent to the B1X export configuration. The upgrade fits an enhanced planar-array antenna, an automatic IFF code changer, adds ECM and ECCM improvements, and allows the system to fire the Rapier Mk 2A/2B missile.

The delivery of up to 12 Pantsir-S1 vehicles was reported in 2012, around the time that the US reported an Omani request for 18 Boeing Avenger self-propelled fire units and 266 Stinger-Reprogrammable Micro-Processor (RMP) Block 1 surface-to-air missiles.

Iraq

Following the 2003 war against Iraq, that country was left with little in the way of air defence – a few air surveillance radars and air-traffic-control radars, plus a number of obsolete anti-aircraft guns. But like the GCC members, it has had to invest in new GBAD systems. The key ingredients of a future integrated air defence system were set out in a 2013 request to the US that included the hardware needed to equip three batteries of HAWK XXI, including six Battery Fire Direction Centers, six High Powered Illuminator Radars, two Mobile Battalion Operation Centers (BOC), three BOC Air Defense Consoles, and 216 MIM-23P HAWK missiles. It also included 40 Avenger Fire Units, and 681 FIM-92H Stinger Reprogrammable Micro-Processor (RMP) Block I Missiles. A large enough quantity of Rapier systems were captured from Iran during the Iran–Iraq War to allow the system to be taken into Iraqi service, but these were phased out around 20 years ago.

Iraq has made some purchases of Russian air-defence hardware. The 9K338 Igla-S (SA-24 Grinch) seems to be the main MANPADS system in current use. A contact for a batch of 24 Pantsir-S1 (SA-22 Greyhound) was signed in 2012, leading to deliveries which allowed vehicles to participate in an Iraqi military parade in 2015.

Following reports that Iraq planned to procure the S-400, in May 2019 the Iraqi Ambassador to Russia confirmed that the planned purchase had been approved by his country. In 2020 the US confirmed that it had deployed PATRIOT systems to Iraq in order to defend Iraqi bases that host coalition troops.

Future Trends

With five countries in the Gulf region now operating PATRIOT, and two operating THAAD, the area probably has a greater concentration of ground-based air defence than nearly any other corner of the world. These systems are not just for show – both are seeing combat use. Meanwhile, combat operations over Ukraine are providing further evidence that in future conflicts, the air threat may not be confined to combat aircraft and helicopters, but will include ballistic missiles, ground and air-launched cruise missiles, and long-range UAVs. The shape of air warfare is changing, and GBAD will have to evolve in turn.

Doug Richardson