The consequences of the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, launched by Russia on 24 February 2022, are being felt globally, and are now forcing nations to rethink their strategic relationships and their security strategies on several levels. Ammunition production and sourcing form a significant part of the defence procurement policies that both support and result from these relationships and strategies which are now being questioned. In order to properly understand these questions, we must first understand how we got here.

Much of our collective defence preparedness has continued to rely on the Cold War strategy of nuclear deterrence. One concern of this strategy was the European belief that minor aggressions, such as those perpetrated by Russia, would go unpunished, should such aggressions require a softer response than nuclear confrontation and a determined NATO, uncluttered by political inaction. By contrast, the American concern was to avoid the risk of entanglement in political matters perceived as largely relating to uniquely European interests. The logically, these opposing concerns should have logically resulted in increased national defence postures for European nations, or a European resolve to form a body capable of acting independently from NATO, but neither of these really seems to have occurred.

The special military operation in Ukraine undoubtedly sought to exploit the perceived Allied and European lack of resolve. Instead of this expected outcome however, the strength of Ukrainian resistance, and the coherence of Western responses prevented a rapid conclusion to the war, creating a subsequent unintended consequence: the heightened risk of inadvertent and uncontrolled escalation, due to the prolonged conflict.

Ammunition Logistics, Heavily Abridged

The concept of military logistics, keeping an armed force supplied with everything it needs, “from beans to bullets”, of course predates Gen. Bradley, let alone NATO, by more than two millennia. The earliest known standing army, and with it, the earliest known military logistics system, was that of the Assyrians (circa 700 BCE). Then as now, when properly executed, the art of logistics provides for the planning and implementation of those actions necessary to achieve military and, by extension, political objectives. These actions, and their basic objective of supporting the troops, form the foundation of any victory, as military professionals well understand. While a part of the military complex since the Assyrians, logistics only relatively recently achieved a degree of autonomy from other military disciplines.

Credit: Mary Harrsch, via Wikimedia Commons

The basic realities of logistics are well illustrated by the apocryphal quote from Napoleon Bonaparte that “an army marches on its stomach”. While the objective toward which Napoleon was marching is left unsaid, there is no doubt that his desired political objective was victory over the ‘enemy du jour’. Achieving such an outcome required proper planning and equally proper implementation, both of which required ‘time consistency’, in effect determining which capabilities and resources were needed, at which point in time, and at which place.

The answers to such questions formed the basis for logistics policies whose implementation required support from experts and dedicated entities (later evolving into supporting institutions). In the case of La Grande Armée, Napoleon’s logistics policy was organised according to a direct and an indirect manner of supplying his troops. Direct supply is that provided by the military logistics organisation, from central supply points, while indirect supply requires obtaining supplies locally. Napoleon’s over-reliance on indirect supply, which required foraging for food and other supplies from the surrounding environment, would nearly decimate his army during the Russian Campaign.

As advanced as La Grande Armée was for its day, their logistics system showed strong parallels with the Assyrian army mentioned above, which similarly relied on local foraging to supply their forces. Proper planning meant the Assyrians couldn’t stay in foreign or neutral locations for extended periods, since their armies then risked exhausting both local supply capacities and/or goodwill. Military actions thus often depended upon seasonality and the perceived availability of food or harvests in the area of operation.

As the ages and technology progressed, reliance on indirect methods of logistics support declined in practicality, and formal direct support structures prevailed, leading to updated logistics policies. These policies naturally mirrored the social, political, and economic trends of the time, seeking to benefit from increased specialisation arising from new organisations and divisions of labour, themselves in turn partially necessitated by the increasing complexity of weapons systems and other technologies.

Two of the oldest such structures, that can still trace their history to the present day, are the British Board of Ordnance and the Danish Tøjhuskomplekset. The former was established circa 1460 in the tower of London, and itself predated by earlier specialist logistical positions. Its purpose was “to act as custodian of the lands, depots and forts required for the defence of the realm and its overseas possessions, and as the supplier of munitions and equipment to both the Army and the Navy”, according to the History of the Ordnance Survey, citing older sources. The Tøjhuskomplekset was created in Copenhagen in 1602 by order of King Christian IV of Denmark, and its name can be roughly translated to ‘War Goods Complex’ or simply the Danish Armoury. This institution was populated by specialists and tasked with supplying the Danish Navy with cannon, shot, gunpowder, rope, sails, timber, tar and all the other elements required for a Navy to operate successfully. The descendants of both these organisations survive to this day.

Institutions such as the Board of Ordnance and the Danish Armoury were instrumental in supporting further technological change in military ordnance, which through specialisation discovered better production methods, enhanced skills, and various means to improve efficiency. One of these technological changes concerned small arms, specifically the migration from muzzle-loaded smoothbore muskets to breech-loaded rifles firing self-contained, metallic cartridges. This technological change, and the military advantages it provided, necessitated increased standardisation, which was better supported by specialist entities.

Credit: NATO/Pall Hall

When firearms were muzzle-loading, smoothbore muskets firing paper- or cloth-wrapped lead balls, local armourers could be relied upon to produce their own ammunition, which involved casting the projectiles and locally sourcing the gunpowder. Yet as ammunition changed from musket balls and round shot, managing the new products in the changing market space required different techniques to cope with the introduction of metallic cartridges. Direct logistics support methods were required to ensure the fit between the weapons and the cartridges. Lack of proper fit could limit the functioning of the weapon, injure the operator(s), or could render the weapon nearly useless. None of these outcomes would be desirable. Improved production techniques and management permitted series production of a consistent cartridge, increasing the soldier’s probability of a kill by improving the major variables. Peter Courtney-Green wrote in Brassey’s ‘Ammunition for the Land Battle’ that “The probability of achieving a kill is a simple probability product: that is, the probability of a kill is equal to the probability of hitting the target multiplied by the probability that the ammunition will have the required degree of lethality multiplied by the probability that the weapon will perform reliably.”

For smaller nations like Denmark, centralising and nationalising the production and distribution of small arms ammunition gained in importance as a way of ensuring the supply and quality, creating the pretext for a well-controlled state-supported natural monopoly. However, unlike in larger European countries, these capacities were not expanded beyond the need for internal defence. Starting in 1914, World War 1 (WW1) was the first modern, global, industrial war and marked a change from the limited wars of feudal Europe, to total war. During WW1, several nations managed to remain neutral. Danish neutrality allowed the nation to escape the devastating effects war and even allowed export trade to continue to both belligerents on both sides of the conflict. A similar policy of realpolitik in WWII failed to discourage invasion and occupation.

Credit: US Navy/Jan David De Luna Mercado

During the interwar period, Europe’s shifting political landscape refocused trade on the UK as Europe’s major trading partner, encouraging shifts away from agriculture towards manufacturing and motivating changes to national monetary policies, however capital controls and reduced capital mobility meant that nations with difficulties were unlikely to recover. Robust, pre-war integrated financial markets may even have obscured the looming war by convincing leaders that economic success was meant security, according to historian Niall Ferguson. As the 1930s spun to a close, the renewed demand ammunition and equipment would see countries becoming dependent on American innovations in mass production to meet their needs.

Credit: US National Archives

The European Ammunition Scene since WW2

At the end of World War 2 (WW2), much of Europe’s industry lay in ruins, though levels of destruction varied between countries. Germany, for example, had very little surviving industrial infrastructure. In contrast, a nation like Denmark had survived almost intact. Economist Ingrid Henriksen wrote that “Economic reconstruction after World War II was swift, as again Denmark had been spared the worst consequences of a major war. In 1946 GDP recovered its highest pre-war level. In spite of this, Denmark received relatively generous support through the Marshall Plan of 1948-52, when measured in dollars per capita.”

The market advances and adapted lessons of mass production from the US supported the bloated production required for the war but which was unnecessary afterwards. Public sentiment, positive in support of the war effort, felt the effects of increased public spending on defence that could not be maintained in the post war era. Political leaders had little choice but to cut production and seek opportunities for privatisation. Considerable demobilisation programs occurred. For comparison, by 1947, the US Army force strength was reduced to less than 10% of its size in WWII.

Almost as a corollary to the Marshall Plan, the US came to regard post-war Western Europe as a potential market for surplus US military equipment and consequently, many western-European nations benefited from low-cost supplies and ammunition from the US. During this period, the US was faced with extremely large, unprofitable factories requiring considerable management to control them. Confronted with this challenge, the US began shifting policy toward decentralised, smaller manufacturing sites for military requirements, according to historian Joshua B Freeman. This was as much a question of management as a question of avoiding public outrage over high military spending in an era rapidly turning toward optimism and peace.

One of the mechanisms thought to support that peace was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO, an international organisation established to maintain political order with particular focus on collective security, was created in 1949 as a way to safeguard western ideologies and Western Europe from perceived threats to those ideologies and the post-war order. In typical political reciprocity the Eastern Bloc formed its own equivalent, the Warsaw Pact, though these were not the only political institutions created to maintain political order. Niall Ferguson wrote: “Over time, American aid in particular became hedged around with political and military conditions that were not always in the best interest of the recipients…to some critics, however, the World Bank and the IMF were no better than agents of the same old Yankee imperialism. Any loans from the IMF or World Bank, it was claimed, would simply be used to buy American goods from American firms – often arms to keep ruthless dictators or corrupt oligarchies in power…”. In safeguarding security, NATO also provided one potential platform for the future export market for weapon systems and ammunition.

For Europe, the 1950 Schuman Plan called for the development of independent European political, economic, and military institutions. While the political and economic aspects were supported (such as the European Coal and Steel Community), hopes for an independent defence force were left unsupported in the 1955 Messina Conference.

At this point in time a third World War, whether conventional or nuclear, was seen as probable or even, inevitable to some, due to the ideological and existential differences between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. This encouraged countries to maintain national production of ammunition, and the formation of NATO also obligated nations to maintain a certain level of defensive capability, including stockpiles of weapons and ammunition. A significant consequence of this was that, in many cases, the national small arms ammunition factories de facto came to ‘live off’ orders from their national armed forces who, in many cases, owned the factories. Additionally, the ammunition they were producing was made according to their armed forces’ requirements and standards, not just with regards to the ammunition itself, but also with regards to testing, packaging and marking.

Consequently, many of the state-owned factories over the years got used to operating in a non-competitive environment, where they effectively had a monopoly on ammunition supply to ‘their’ armed forces, as well as renovation and disposal of expired stockpiles. From around 1970, and over approximately the next three decades, several factors conspired to negatively influence the European ammunition production scene:

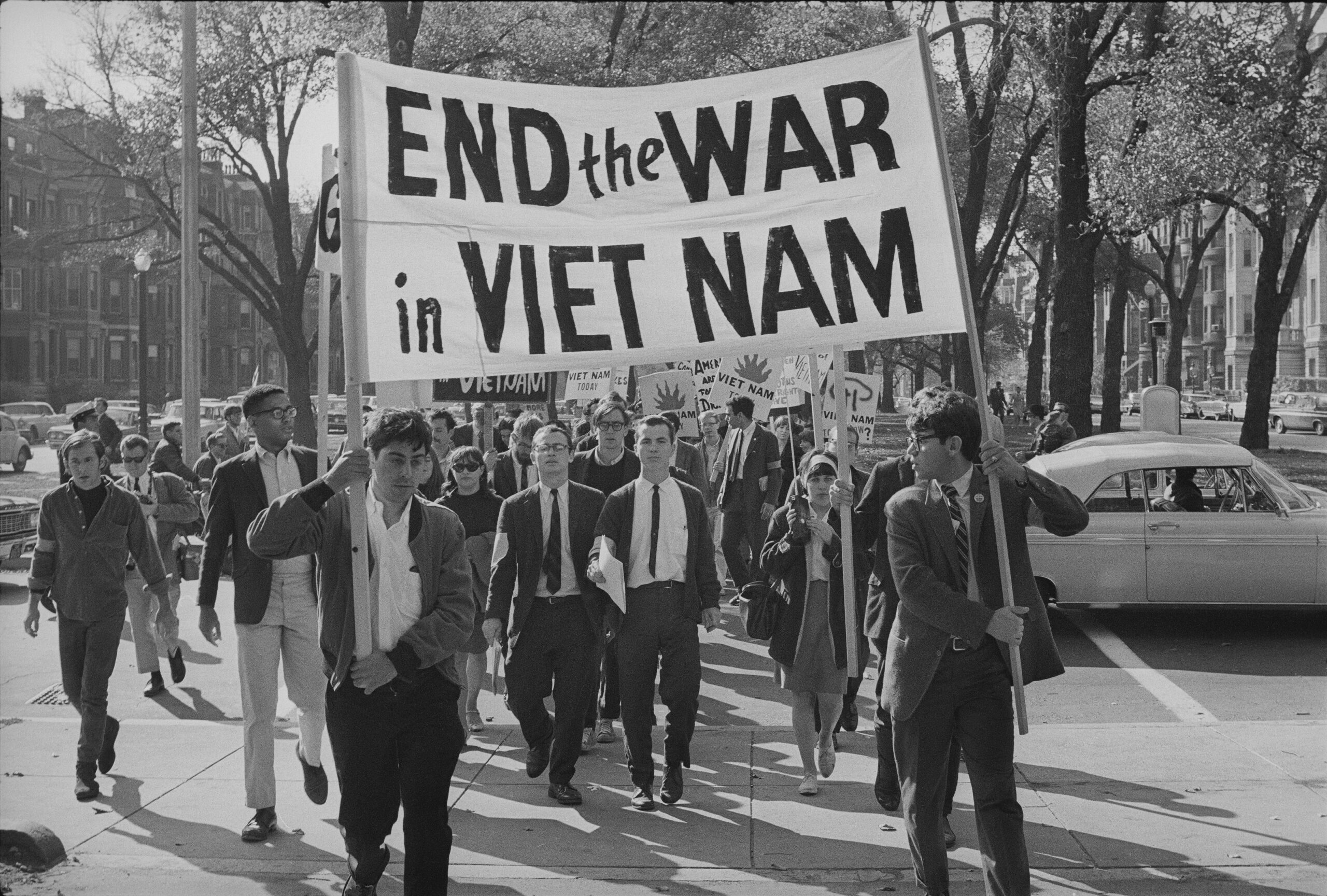

Firstly, the 1970s saw the rise of a peace movement in many Western countries. Due to the risk of a conventional conflict directly between NATO and the Warsaw Pact going nuclear, and resulting in global destruction, both sides of the Cold War instead involved themselves in a series of proxy wars around the world, mainly in the Middle East, the Far East and Africa. This allowed the Western powers (primarily the US) to engage in ideological battle with their Eastern counterparts (primarily the Soviet Union), with little risk of a major, direct conflict. The appearance and rise of the peace movement can be tied to the fact that many of these proxy wars were regularly broadcast to the public, giving a front-seat view of the realities of these wars. Unlike WWII, the many proxy wars proved increasingly difficult to justify, politically or militarily. Peace movements increased pressure on Western governments to transfer defence spending to other areas that were seen as more valuable to society. Essentially, public demand for national defence markedly declined. At the same time, lower levels of investment from individual non-US NATO nations were enabled by free rider behaviour. Lower defence investment in turn meant less than efficient levels of NATO output.

Credit: Frank C. Curtin, via PBS

Secondly, less than a couple of decades later, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union in 1991, and the end of the Cold War, saw the (perceived) end of the threat of a conventional war in Europe. This provided further impetus for drawdowns of national forces in Europe, including the large, cold-war stockpiles of weapons and ammunition, and for a reduction in the continuous need for ammunition for training. The absence of a clear threat in the aftermath of the Cold War found allied nations confused about the New World Order. Defence budgets lacked justification with their apparent ideological foe vanquished. Nations searching for meaning, unity, and direction found none resulting from the experience of Operation Desert Storm. Their continued lack of focus and desire was evidenced by their failure to act decisively in the early days of the Bosnian War.

Thirdly, the creation, of the European Union in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty, obliged member states to conduct as much as possible of their government procurement via open, international bidding which marked a policy shift by multiple nations toward international tenders in supporting their ammunition requirements.

Lastly, with military budgets increasingly constrained, defence managers implemented modern business methods and strategies for procurement and production. While lean strategies may improve efficiency for some organisations, they do not necessarily provide for effective competitive strategy, nor do they replace budgetary oversight. With improvements in technology, weapon systems and defence platforms increased in complexity, requiring more non-operational activities such as training. Consequently, non-operational time may be more important to battlefield outcome than operational time. Such investments in personnel complemented the weapon systems and were seen as an incentive for positive long-term consequences.

Did the above points create a perfect storm which reduced European defence posture and preparedness? For small arms factories in Europe, the consequence was that their previous main customers, their national armed forces, severely reduced their procurement volumes, often to levels that were too low to ensure the survival of the factory and, at the same time, often started procuring ammunition through open, international tenders.

For many smaller countries such as Spain, Portugal, Denmark, and The Netherlands, which had relatively limited ammunition requirements, the transition to Just-In-Time production and international tenders meant that the ammunition requirements coming from the national MODs were now insufficient to keep the national ammunition factories in business.

Added to this, competing on the international military and civilian markets was often fraught with difficulties, especially for factories that had previously operated in a ‘safe’, non-competitive environment. On the military markets, a producer was either competing in an international tender against several other producers, or the potential customers were trying to support their own national industry and, as such, were disinclined to buy from abroad. On the civilian markets, requirements in terms of performance and testing were different from the military, making transition difficult for many factories, unless they were already used to producing ammunition for the civilian market. Additionally, for some countries, the potential negative publicity implications of having ammunition produced in a national factory, appearing in criminal investigations elsewhere were considerable.

The peacekeeping and peace support operations in the Balkans, that started in the early 1990’s, were insufficient to boost procurement and production numbers for small arms ammunition, and the concurrent Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm in the Middle East were also quickly replaced by similar peace support efforts.

Credit: US Army/Markus Rauchenberger

The result was that a number of European countries, such as France, The Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and Denmark, completely abandoned national production of small arms ammunition. In some cases, attempts were made to privatise the production facilities but, for the reasons discussed above, this met with only moderate success.

The New Normal

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched an invasion of neighbouring Ukraine, and Europe suddenly awoke to a major war on their doorstep – something that had last happened 77 years before, and had not been considered a realistic possibility since the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in 1991.

Concerning ammunition logistics, Western countries were faced with a quandary. Due to the factors reviewed above, national ammunition stockpiles were strictly limited, while at the same time, Western states were eager to support Ukrainian defence without creating a context for escalation. One way of doing this was to donate ammunition. As the European security situation had changed overnight, countries became nervous that they now lacked the capacity to supply themselves. This was foreshadowed during the 2011 Operation Unified Protector (OUP) when countries such as Denmark found themselves running out of precision-guided bombs within days of operations commencing, and expectations that the US would provide munitions support during OUP were greatly overestimated. While stockpiling such weapons is a considerable investment, the lack of sufficient resources is embarrassing for the state and its allies alike, especially when such weapons are considered an essential capability.

Credit: US Army/Alex Manne

With European abandonment of national small arms ammunition production after the end of the Cold War, countries now face a choice with regards to how they want to supply their armed forces with small arms ammunition in the future. Perhaps greater defence spending will permit new opportunities for national investment. With NATO member states pursuing a target of spending 2% of GDP on defence, nearly EUR 100 Bn of additional funding could be made available. It’s not clear if this funding increase will be supported by additional taxation or by cutting existing programs. Individual states and their voters will have to decide.

The Cost of Scaling Up

The decision to invest in a small arms ammunition capacity is as much an issue of economics as of military autonomy. The separation of budget allocation and military spending provides for an age-old conflict. Political financial controllers contrast with military decision makers seeking high quality outcomes. Regrettably, inefficiently low production rates for small arms ammunition are unlikely to motivate national investment. According to author John N. Petrie, not knowing the outcome or timing of international tenders reliant on industrial partners, who are also obligated to supply their own states (or the highest bidders) first, greatly complicates the task of military decision makers and leads to the unintended consequence of diminished control.

Do the advantages of constructing a new national small arms ammunition production plant make sense? Such a question bears significant familiarity to those faced by Napoleon and La Grande Armée. Logistics requires proper planning and implementation, both of which require time consistency in answering which capabilities and resources are needed now and which are needed for anticipated future action. While we might be able to risk an undesired outcome in a conflict such as OUP, can we risk the same with threats closer to home?

Scott E. Willason and Thomas L. Nielsen

![2025 in the Western Balkans: A year-end SITREP Soldiers from the Czech company, part of the EUFOR Multinational Battalion, conducted a series of joint training exercises in Mostar alongside operators from Bosnia’s State Investigation and Protection Agency (SIPA). [EUFOR BiH]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Handshake_EUFOR-BiH-218x150.jpg)