From earthquakes, floods and wildfires on the natural side of things, to man-made, mass-casualty events, as such incidents unfold, they present first responders and emergency personnel arriving on-site with typically chaotic scenes. Implementing immediate, coordinated and well-rehearsed control procedures is needed from the start, not least of which is the establishment of an incident command post.

A major incident unfolds in a European setting and whether confined within one national border or spanning several, it requires an urgent, co-ordinated and effective response from a full gamut of blue-light emergency first responders and, potentially, coordination with other security services and armed forces, depending on the type of incident. Whether a terrorist attack, a plane crash, a rare European mass shooting, or an industrial accident involving fire and chemicals, no matter what the emergency, those services responding will, as far as is possible, follow standard operating procedures, guidelines and/or latest conventions laid down in their local forces’ or wider nationwide/European operational doctrines.

This article takes a look at some of the strategic mechanisms of European civil protection as it relates to major incidents, as well as the general tactical, on-the-ground considerations required for the establishment of an on-site incident command post (ICP).

Credit: Baudouin Wisselmann, via Unsplash

European Civil Protection – a Glimpse

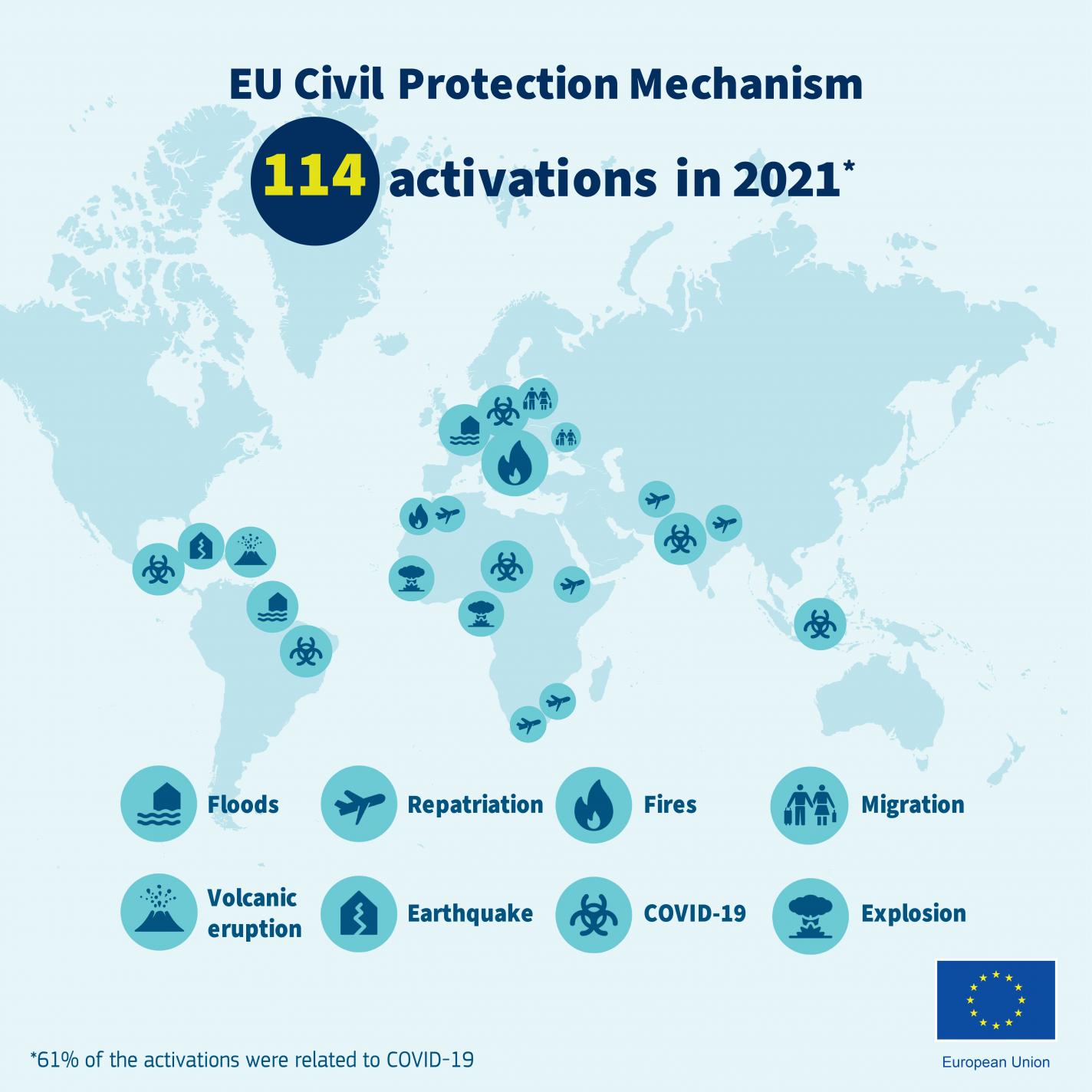

The European Commission relatively recently in 2019 upgraded what is known as the EU Civil Protection Mechanism and created rescEU, a process to protect citizens across the union from disasters and to manage emerging risks. Fully financed by the EU, rescEU has established a new European reserve of resources, (the ‘rescEU reserve’), which includes a fleet of firefighting planes and helicopters, medical evacuation planes, and a stockpile of medical items and field hospitals and mobile shelters that can respond to health emergencies. The EU is also developing a reserve to respond to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear incidents. If an event overwhelms the ability of member states to help each other, especially when several countries simultaneously face the same type of crisis, then the EU will provide this extra layer of protection through the rescEU reserve, thereby ensuring a faster and more comprehensive response.

Credit: Chris Gallagher, via Unsplash

On the ground, individual member states’ emergency services will be responsible for the roll-out of ICPs on site, as required and as necessary, whose staff, in turn, should be aware of the availability of resources provided by the rescEU, if an incident is of such magnitude that such resources are called on. Indeed, it is up to the member state to request assistance via the EU Civil Protection Mechanism if the scale of an emergency overwhelms the possibilities of a country to respond on its own. Once activated, the EU channels offers of assistance, made available to member states, through its Emergency Response Co-ordination centre. To strengthen the EU response to forest fires in 2022, the commission financed the stand-by availability of a rescEU firefighting fleet, which involved 12 firefighting planes and one helicopter placed at the disposal of all member states in the event of emergencies and resourced from Croatia, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Sweden.

In the case of such fire incidents, European response capabilities and command post deployment exercises are on the itinerary of several organisations; the Finnish Emergency Services Academy, Pelasiusopisto, for example, provides vocational education for firefighters, sub-officers, fire officers and emergency response centre operators in Finland, but also takes part in Europe-wide training. It offers a wide variety of specially-tailored skills for national and international professionals in the rescue and emergency field and is responsible for ensuring the training and recruitment of Finnish experts is in line and suited to international civil protection standards so they can be deployed overseas, if required.

The academy actually took part in a table-top and ICP exercise based on multi-scenarios that cover natural, technological and man-made disasters co-ordinated during the 2018/2019 timeframe and conducted in Q1 2019 by a Consortium led by the French Directorate General for Civil Protection and Crisis Management. The exercise tested the national and European response capabilities in cases of major destruction with aspects of a major crisis requiring the deployment of civil protection modules, simultaneously, on several sites. Different scenarios were played out in virtual simulation using a variety of new technologies, with the command post exercises organised at the Civil protection and Fire Emergency Services National Training Centre (ENSOSP) in Aix en Provence and co-financed by the European Commission Civil Protection Financial Instrument (785563-UCPM-2017-EX-AG).

Credit: Michael Held, via Unsplash

rescEU Overall

Overall, rescEU has seen a relatively soft harmonisation and introduction for command and control and civil protection during major European incidents, including the aim to increase cross border and international interoperability, as well as compliance with other existing systems, such as UN systems and US Incident Command System (ICS). While it was meant to be integrated into the jurisdictional basis of EU civil protection, its introduction has, according to some analysts, so far only resulted in relatively small changes in terms of resources and knowledge management.

With natural disasters over recent years seemingly on the rise, such as wildfires in Sweden and Greece, and flash floods in Spain and France, with newer lessons learned, further suggestions to improve European Civil Protection beyond rescEU have been posited. Among these is the proposal to move from the already satisfactory modular system of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism (EU CPM) to an integrated, more robust European Command System, one fully interoperable with other existing mechanisms, such as the aforementioned US ICS and UNOCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs).

The ICS, for instance, comprises a standard management hierarchy and procedures for managing temporary incidents of any size using procedures that should be pre-established and sanctioned by participating authorities, with all personnel stakeholders well-trained in all aspects before an incident occurs. The system includes procedures to select and form temporary management hierarchies to control funds, personnel, facilities, equipment, and communications and is a system designed to be used from the time an incident occurs until the requirement for management and operations no longer exist. Incident command structure is organised in a flexible and modular way so as to expand and contract as needed by the incident scope, resources and hazards with Incident Command established by the first arriving unit.

As far as immediate facilities are concerned, ICS uses a standard set of facility nomenclature, several pre-designated incident facilities will be considered at any incident as response operations can be very complex requiring cohesive elements holding response personnel together as they work at different and often widely separate incident facilities and locations. Of these facilities it is the ICP that is, perhaps, the most important.

Before we take a closer look at ICP facilities, a few aspects of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism are worth a mention to convey more of the complexity of the whole civil emergency response picture. At the heart of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism is the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC), which co-ordinates the delivery of assistance to disaster-stricken countries, such as relief items, expertise, civil protection teams, specialised equipment and rescEU resource. The ERCC operates 24/7 and can help any country inside or outside the EU affected by a major disaster on request from national authorities or the UN, delivering a well-coordinated response to human-induced disasters and natural hazards at European level, thereby avoiding duplication of relief efforts. It can also liaise directly with the national civil protection authorities of the country in need to help lessen the burden on contributing states.

Credit: European Commission

The Incident Command Post

For any incident, no matter how strategically co-ordinated it might become, it must have some form of tactical Incident Command Post on the ground, often established by the ‘first’ first responders arriving on scene. It might be located in a vehicle, trailer, tent, or within a building, but it must be in a location outside the immediate and potential hazard zone, though close enough to the incident to maintain command. The ICP is the location where the incident commander operates during response operations and there is only one ICP per incident or event, with its name typically determined by the name of the incident locale, for instance: ‘Bataclan ICP’, or ‘Grenfell Tower ICP’. It is key to strengthening command and co-ordination on ground during disaster-related crises and incidents with first responders.

The ICP is equipped with computers and other communication facilities to provide a link between on-site and national/international/EU decision support and command and control mechanisms. This helps to coordinate multi-agency interventions to incidents such as regional flooding, landslide, oil spill, HAZMAT, off-airport aircraft crash, and others.

An ICP serves an important purpose for first responders and/or security services to manage an emergency efficiently and safely. When a large-scale emergency incident occurs, a command post is typically established, if feasible, often by the first service arriving on site. An ICP is intended to provide a mechanism and location from which emergency responders and management can converge to effectively coordinate and discuss responses to an incident and ongoing actions required. Such ICPs become the epicentre for directing and co-ordinating all emergency response activities. A service’s operational doctrine will guide the service in selecting the right location for such an ICP, with sites for a specific incident chosen based on the location of developing circumstances, safety, and ability to establish reliable communications networking and connecting all personnel typically using TETRA.

Credit: Toutenkamion

Some of the guidelines to be followed by emergency team management in identifying acceptable locations for an ICP include ensuring adequate space for the size of staffing as well as fluid footfall of on-the-ground responders, for which 24-hour accessibility is crucial. Alongside this, personal hygiene facilities are necessary for both in-situ staff and responder visitors. The ICP should also be adequately sheltered from natural elements. Importantly, the location must be suitable for the ICP’s communications resources, (mobile/PMR/TETRA/radio/internet), and incorporate conference and briefing rooms. It must also be located in a safe location vis a vis the ongoing incident, ensuring all staff are safe and secure. Once located, ICP staff must ensure other relevant parties are notified of its location, including through the provision of maps/driving directions/communications details, together with staging areas and incident base locations. That said, being prepared to move to a different location should the need arise in an unfolding incident requires the ICP team to reconnoitre and be aware of suitable alternative locations.

Inside the ICP, communications may eventually include fixed phone lines, but wireless/cellular, TETRA two-way radios, and email will be essential from the start, with additional communications equipment such as portable radios with chargers and accessories, may soon become necessary to implement emergency communication procedures in protracted scenarios. Communications with government agencies, between distinct police forces, specific municipalities, and any identified emergency contractors necessarily involved in, say, search and rescue (SAR) operations, can be conducted on portable radios. ICP emergency managers need to ensure their communication equipment includes enough phone lines for all staff, computers and internet access, recharging stations for mobile phones, and TETRA radio communications equipment with established frequencies. Furthermore, callsigns, timed/regular radio checks, and an emergency communications schedule are essential to ensure all operatives are safe and accounted for.

Credit: Toutenkamion

The First Exercise

The first European civil protection exercise to explicitly test the ‘Solidarity Clause’ in the Lisbon Treaty was a European disaster-response simulation exercise in Carcassonne, France, around 10 years ago. This took the form of an Incident Command Post exercise to test the capability of command posts from different countries to cooperate during a major earthquake. While no operational teams were deployed, the command posts worked under realistic conditions of the kind personnel would encounter in the field. The exercise was organised by France and involved civil protection teams from Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland and Spain. A European civil protection team reinforced by a liaison officer from the European Commission’s Monitoring and Information Centre in Brussels co-ordinated the international teams, with the exercise 75% co-financed by the EC under its Civil Protection Financial Instrument.

Tim Guest