The War in Ukraine and a general increase in military spending is pushing several countries to modernise their ageing naval fleets, thus boosting the order books of shipyards after years of negative outlook. If this is good news, the situation remains complicated within the EU, where shipbuilders’ economic outlook is less prosperous compared with Asian and US competitors, and coordinated programmes often struggle to kick off.

In a study published in 2020, the EU Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) noted that between 1999 and 2018, EU navies lost more than 30% of their frigates and destroyers and more that 20% of their submarines. Surprisingly, these significant reductions came at a time when navies were increasingly called to action. Tensions in the Mediterranean, Black and Baltic Seas, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, coupled with the “intense geopolitical competition” taking place in the Indo-Pacific region and around the key maritime chokepoints all represent crucial threats to EU security. More than 70% of the EU’s external borders are maritime and combined, its member states form the largest exclusive economic zone in the world. Maritime communication lines remain crucial for trade and oil and gas supply, and undersea cables account for 99% of global data transmissions.

By 2025, EU countries are expected to spend EUR 55.5 Bn on maritime technologies. However, official EU documents report that less than 20% of investments in defence programmes are coordinated among its member states. In the absence of a common foreign policy agenda, cooperation is pursued only when the political objectives and operational requirements of two or more EU countries converge.

Moreover, several of the most important member states in military terms have national shipyards they can be relied upon to modernise their respective fleets: Fincantieri for Rome, Naval Group for Paris, Navantia for Madrid, Lürssen and ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems for Berlin, Saab for Stockholm, and Damen for Amsterdam. Most of these are first-class system integrators, with a strong positioning on the global market.

So far, EU member states have fought to keep each of these national champions alive, often for electoral or national security considerations (keeping occupation levels unchanged, maintaining national know-how, etc.). On paper, each member state has officially identified collaboration as an interesting opportunity in industrial, economic, and strategic terms. Indeed, joint programmes help in reducing costs and increasing interoperability. Yet in practice, EU members have largely rejected calls for EU-wide cooperation coming from the European Commission or the European Parliament.

On the one hand, they act in this way to protect their respective national companies. On the other, they have done so because joint projects led by consortia have often proved ineffective so far. As a result of a compromise among several member states, common programmes are often a sub-optimal solution in terms of operational requirements. Their management might be complicated due to the high number of relevant stakeholders, resulting in products delivered behind schedule, and sometimes no longer consistent with the initial needs and scope. Cooperation in the naval sector therefore remains mainly bilateral or multinational, and limited to specific programmes.

Credit: US Navy/Petty Officer 3rd Class Ezekiel Duran

For their part, shipyards are generally not attracted by joint development programmes, as a significant part of their backlog originates from export, following tenders in which they often compete with other European producers. And in some cases, export opportunities can be found in the EU countries that do not have the know-how needed to build up their own fleet.

As with other defence-related industrial segments, a multiplicity of producers and systems has been the preferred choice so far. However, the evolving situation of the global naval market requires a new approach. The World Defence Shipbuilding 2022 report confirms that East Asian countries, in particular China, Japan and South Korea have joined the club of the largest producers of military vessels. Even though they remain significant on the global market if considered in aggregate terms, EU shipyards are lagging behind. In the short- to mid-term, they will lose much of their competitiveness on the global market, and their aggregation might become the only solution to survive mounting international competition. For the time being, companies and states are simply trying to maintain the status quo, and aggregation is not on the agenda. Indeed, aggregation would mean a sacrifice for each shipyard, as it would require profound changes in their structure, with consequent job losses.

In the coming years, EU countries will have to redefine the structure of their shipyards. Focusing on enhancing the position of the whole European shipyard sector rather than the positioning of each shipyard would probably be the most effective solution. However, such a shift is almost impossible without a rapprochement of foreign policy agendas, which currently seems unlikely. Again, member states officially agree that a broader integration of the European defence-industrial base is crucial to maintaining the bloc’s independence, as all the EU strategic documents on the matter stress. Maintaining the status quo will likely bring about a loss of strategic autonomy, as foreign buyers might put the survival of European shipyards at risk.

Shifting from the multiplication of national naval programmes to an EU-wide coordination of naval programmes might be a first step to reconfigure EU shipyards and to work on shaping the future functioning of the European market. Numerous EU tools might help in this shift and, as will be further analysed, some forms of coordination are already emerging.

Coordinating Naval Programmes at EU Level

To help EU member states fill their capability gaps and encourage them to favour EU solutions to off-the-shelf purchases abroad, the EU is trying to revamp a range of management and financial tools that have barely been exploited so far. The Coordinated Annual Defence Review on Defence (CARD) is intended to support member states in the identification of common capability gaps and, consequently, of potential cooperative programmes that might be developed jointly by using EU tools. The Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) provides a framework and a structured process to gradually deepen cooperation starting from the most sought after missions, according to CARD reports. The European Defence Fund (EDF) plans to pledge EUR 8 Bn for defence projects between 2021 and 2027 with funds allocated to the programmes selected through an annual call for proposals. The relevant topics, which include naval combat and underwater warfare, are identified according to existing PESCO programmes and the priorities identified in the CARD and in the Capability Development Plan (CDP) outlined by the European Defence Agency (EDA).

Concerning the coordination of programmes, member states have the option of entrusting the Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en matière d’ARmement (OCCAR) with facilitating and managing cooperative armament programmes through their life cycle. OCCAR’s portfolio currently includes 17 major armament projects, five of which concern naval vessels, with different configurations and objectives.

Credit: Italian Navy

Among these, the FREMM programme was launched in 2005 for the construction of 18 multi-mission frigates. Italy and France remain the only participants, and the vessels produced within the programme are slightly different in terms of equipment. Similarly, the LSS (Logistic Support Ship) programme is another Franco-Italian collaboration producing substantially different ships. Another notable example is the Maritime Mine Counter Measures (MMCM) programme, under which France and the UK aim to equip their navies with autonomous mine hunting capabilities by 2024.

Despite being integrated into a more European framework, these programmes are managed with a standard structure, which sees the collaboration of two states and the relevant national companies. In recent years, however, an interesting example of coordination has emerged in the European landscape.

Naviris: A New Approach for Coordinating Naval Programmes?

In 2019, Italian company Fincantieri and the French Naval Group negotiated the acquisition of Chantiers de l’Atlantique (a shipyard located in Saint Nazaire, France) and decided to establish a 50/50 joint venture. The main idea was to combine their respective expertise to launch new programmes and find new export opportunities, thereby somehow trends that were emerging in the global market.

Since then, Naviris has been involved in six R&D projects and has overseen the development of the European Patrol Corvette (EPC). Approved in November 2019 as part of the third batch of PESCO projects, the EPC programme aims to design and developing a shared modular corvette, with a displacement of under 3,000 tonnes, a maximum draft of 5.5 m and a length no longer than 110 m. The development of a European Patrol Class Surface Ship (EPC2S) is defined as an “EU-wide approach for modular naval platforms adaptable to various sea basins and member states’ requirements/programmes”. It was identified as a potential area of cooperation in the 2020 and the 2022 CARD reports. Led by Italy, the programme also involves France, Spain and Greece, and was joined by Romania in June 2023. The EDA supports participants through the development and the adoption of Common Staff Targets (CSTs), Common Staff Requirements (CSRs) and a Business Case (BC). The first prototype is scheduled for 2026-2027.

Credit Courtesy of Naviris

In December 2021, Fincantieri, Naval Group, Naviris and Navantia submitted an industrial offer for the Multirole and Modular Patrol Corvette (MMPC) call opened within the European Defence Fund’s framework to support the development of the EPC programme. In July 2022, Naviris was officially appointed as prime contractor for the consortium, and was joined by Greece, Denmark and Norway. This grant is valued at EUR 60 M and involves a 24 month initial development phase dedicated to technological building blocks for military units and the initial study for a joint project, which does not include a combat system, at least for the time being. As of June 2023, the partner countries were still finalising the Memorandum of Understanding, and the programme was expected to start in the autumn. In March 2023, the European Commission issued a second call for tenders dedicated to the completion of the original design and details of the MMPC, which may end with the creation of prototypes of the platform. The funding for this second call amounts to EUR 714 M. A Naviris source told the author that the exact list of participants to this second call, whose deadline expires in November 2023, is still to be defined, and will likely include only the nations that plan to produce and procure the vessels at the end of the study.

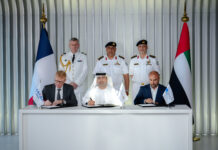

Between 2020 and 2022, Naviris has been prime contractor of a feasibility/de-risking study for the modernisation of the Horizon class destroyers in service with France and Italy, jointly developed between 2000 and 2010 by Fincantieri and Naval Group. Following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding during the 2023 Paris Air Show, the joint venture was officially selected for the Mid-Life Upgrade (MLU) of the platform and its combat systems, while co-contractor Eurosam will work on the modernisation of air defence systems. According to sources in Naviris and Fincantieri, the joint venture can be considered a success story so far, with the EPC programme progressing on schedule for the time being.

Credit: US Navy/Petty Officer 3rd Class Kenneth Abbate

Is Coordination Enough to Solve Market Fragmentation?

Most official EU documents argue that coordination in the naval sector is crucial to protect EU interests. The need for “effectively and comprehensively” assessing security challenges at sea and responding to them is so strong that the naval operational environment is the only one with a dedicated EU strategy. First approved in 2014, the EU Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) identified cooperation as a good way to develop the “necessary sustainable, interoperable and cost-effective capabilities” required to protect EU interests.

In the ‘Enhanced EU Maritime Security Strategy for evolving maritime threats’ release published on 10 March 2023, the European Commission reiterates the need to step up the EU common response to naval threats by developing a full spectrum of maritime capabilities. The EU has committed to develop common requirements for surface and underwater defence technologies, build interoperable unmanned systems and joint test and experimentation exercises to develop future maritime capabilities. It will also increase modern mine countermeasure capabilities and support the development of joint enhanced maritime patrol aircraft capabilities.

When it comes to European defence, the lack of consistent political commitment from member states often ends in lofty announcements followed by insufficient action, or, more often, simply remaining on paper, despite the official commitments undertaken by EU governments when signing official documents. As regards shipyards, at a time when China is deciding on mergers to create a few big players in the market, mergers are no longer on the agenda in Europe, with competition between shipyards remaining the norm in recent years.

The relationship between Naval Group and Fincantieri is an interesting example. In February 2018, the French L’Agence des participations de l’État (APE) and Fincantieri Europe signed a share purchase agreement for STX France, supposed to mark the last step of a year-long acquisition dispute around St.Nazaire’s Chantiers de l’Atlantique. According to the preliminary agreement, the Italian group was expected to purchase a 66.6% share of STX France for EUR 79.5 M. However, the French state (a 33.3% shareholder of STX France with pre-emption rights on the remaining shares) opposed the agreement for several reasons, including job preservation, maintaining local production, and avoiding a technology drain abroad. Worried about Fincantieri’s operations outside Italy (mainly in the US), France finally offered the company a 51% share of STX France. Following Fincantieri’s refusal, Paris decided to purchase the remaining STX France shares, thus becoming the 100% shareholder. After several years of negotiations, Rome and Paris officially announced the termination of Fincantieri’s acquisition programme in January 2021, officially due to the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Credit: Cédric Quillévéré (via Wikimedia Commons)

The ties between these two shipyards highlight the current distortions of the EU naval industry: they share a 50/50 joint venture and work together on some EU-wide programmes, but remain competitors in some tenders, such as the one for the corvettes in Greece (one of their EPC partners). In the meantime, Fincantieri is also one of Naval Group’s subcontractors for some joint projects, a rare case in which the company supplies something to another EU country that has a primary role in shipbuilding, a Fincantieri source told the author. The same source also recalled that all the main European countries have their own shipbuilding capacities, which makes them “self-producers”. In other words, this means that the respective national Navy is the main reference customer for each of these companies.

As EU nations do not seem particularly committed to finding viable and long-lasting solutions to the problems affecting shipyards, a solution might come from the shipyards themselves. Indeed, they might use their experience and lessons learned to suggest how the EU naval market can evolve. In his intervention during the first Euronaval talks in June 2023, Davide Cucino, head of European Union Affairs at Fincantieri and Chairman of SEA Naval, noted that a stronger collaboration among European shipyards and between shipyards and users is crucial to find the best balance between a complex industrial development, characterised by long life cycles in a changing security environment, and limited budgets. SEA Naval is a permanent working group established within the Shipyards’ & Maritime Equipment Association (SEA Europe), which advocates for European shipyards’ priorities. The idea is to support EU institutions and members states by providing an industrial point of view and expressing their needs when it comes to EU programmes and the European Defence Fund. It includes 90% of naval systems integrators and shipyards in Europe, namely Damen, Fincantieri, NVL, Naval Group, Navantia, Saab, and thyssenkrupp Marine Systems. Three industry associations Assonave (Italy), GICAN (France) and VSM (Germany) are also part of the working group.

So far, the EPC programme seems a good starting point towards stronger cooperation at the European level, and Naviris is proving effective regarding programme coordination, with projects progressing on schedule. According to the interviewed industry sources, Naviris might go beyond the coordination of a couple of joint naval programmes, paving the way to a transition towards a more integrated sector. In fact, this is one of the reasons the joint venture has been established. “Confronted with similar market challenges on both sides of the Alps, Fincantieri and Naval Group are pooling a portion of their strengths to jointly develop new synergies and retain their leadership position. Building our sovereignty and controlling our future is tantamount to reinforcing our autonomy”, the Naviris’ website states.

Despite the fact that the direction to take and results to be achieved are yet to be defined, a profound transformation of the EU naval market might be the only solution that European countries possess in order to maintain their strategic autonomy and avoid buybacks from non-EU companies. This is particularly important given that competitors are continuing to grab market share, and the capability shortages triggered by the War in Ukraine might divert attention away from naval programmes, potentially risking the progress made to date.

Guilia Tilenni