There is over a century of broad amity between the United States and the United Kingdom. The defence and security alliance between the United States and the United Kingdom is, indeed, a special one. Americans and Britons fought alongside each other in two world wars, Korea, and several conflicts in the Middle East. Both were pillars of NATO throughout the Cold War.

Some of the most prominent and significant US-UK defence and security relationships have been daily routine for decades and thus not often the source of headlines or controversy. One of these is basing. The United States has had military bases on British soil since 1942. Although the size and scope of these bases is reduced since the height of the Cold War, significant US air base infrastructure continues to exist in the UK. Approximately ten thousand US military personnel, as well as significant numbers of contractors and civilian employees, are based in the UK.

Credit: US ANG/Senior Airman Wesley Jones

Sensitive Issues

Two of the deepest relationships between the US and UK are in more sensitive areas. The USA and UK have worked together in the area of nuclear weapons technology since collaboration on the Manhattan Project. After the war, Britain set up its own nuclear weapons programme, but by the late 1950s British and American scientists and engineers were working closely once again. There is a comprehensive agreement, dating from 1958, on nuclear weapon technology. It has been periodically revised, amended, and extended. While cooperation in this area is very close, the exact details are highly sensitive. Figures from some years ago indicate thousands of person-days in visits by UK persons to US sites and activities relevant to nuclear weapons programmes. Political and economic questions about the future of the UK nuclear deterrent, which at present is the venerable Trident programme, will have a direct bearing on this cooperation.

Another area of close cooperation is the ‘Five Eyes’ agreement. Dating originally from US-UK cooperation in intelligence collection in World War II, Five Eyes is an intelligence alliance. The original US-UK agreement expanded to include Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. While each country has things that they do not share, there is widespread liaison as well as sharing of raw and finished intelligence. The exact details of this cooperation are, understandably, shrouded in secrecy. Numerous sources, speaking off the record, attest that the overall relationship is very good both at the headquarters level and at operational levels. It should be noted that there are numerous other agreements in a number of somewhat less highly sensitive areas, such as chemical and biological defence, with decades of history of technical cooperation along those lines.

Cooperation extends down to the lower levels. Across the various branches of the military, relationships between US and UK counterparts are good. Forces train with each other, both in the US and UK, but also in joint exercises with NATO and elsewhere. By all accounts, the relationships at service and unit level are good. Numerous liaison and exchange officers serve in various roles in each other’s country, at various levels. A general air of professional respect exists and serves as a weighty buffer against frictions. Jokes about being divided by a common language aside, a common language helps significantly.

Current Collaborative Efforts

All of those areas of cooperation have been running in the background for decades. New issues come up, and some of them are things that really do require some coordination. Ukraine is obviously the big story of the day. The US and UK are working closely on arming and supplying Ukraine in its existential struggle. This is not merely a bilateral effort, but a multi-lateral one in which both the US and UK are leading by example. The extent of unilateral versus bilateral versus multilateral efforts is hard to unpack at present, and likely to be a useful subject for future discussion.

Credit: USAF/Staff Sgt. Gaspar Cortez

The F-35 fighter programme, which has been analysed in this magazine numerous times, is an emblematic example of US-UK cooperation. An American advanced fighter jet programme which has been in development for decades, the F-35 has entered or will be entering service in a number of countries, including the UK. Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor, but like any such intricate item, it has a complex array of subcontractors and a complicated supply chain of components. The UK is foremost on the list of F-35 components from non-US suppliers. The F-35 includes an ejection seat from Martin-Baker, a refuelling probe from Cobham, and tail components from BAE Systems. According to Lockheed Martin’s own releases, it claims to have over 100 UK firms in its supply chain for this new fighter. Thousands of UK jobs are supported by this large procurement effort. The F-35B is in service in the UK and USAF F-35As are being based at RAF Lakenheath in increasing numbers. While the F-35 is by no means the only major procurement project with US and UK involvement, but it is one of the biggest.

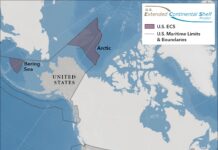

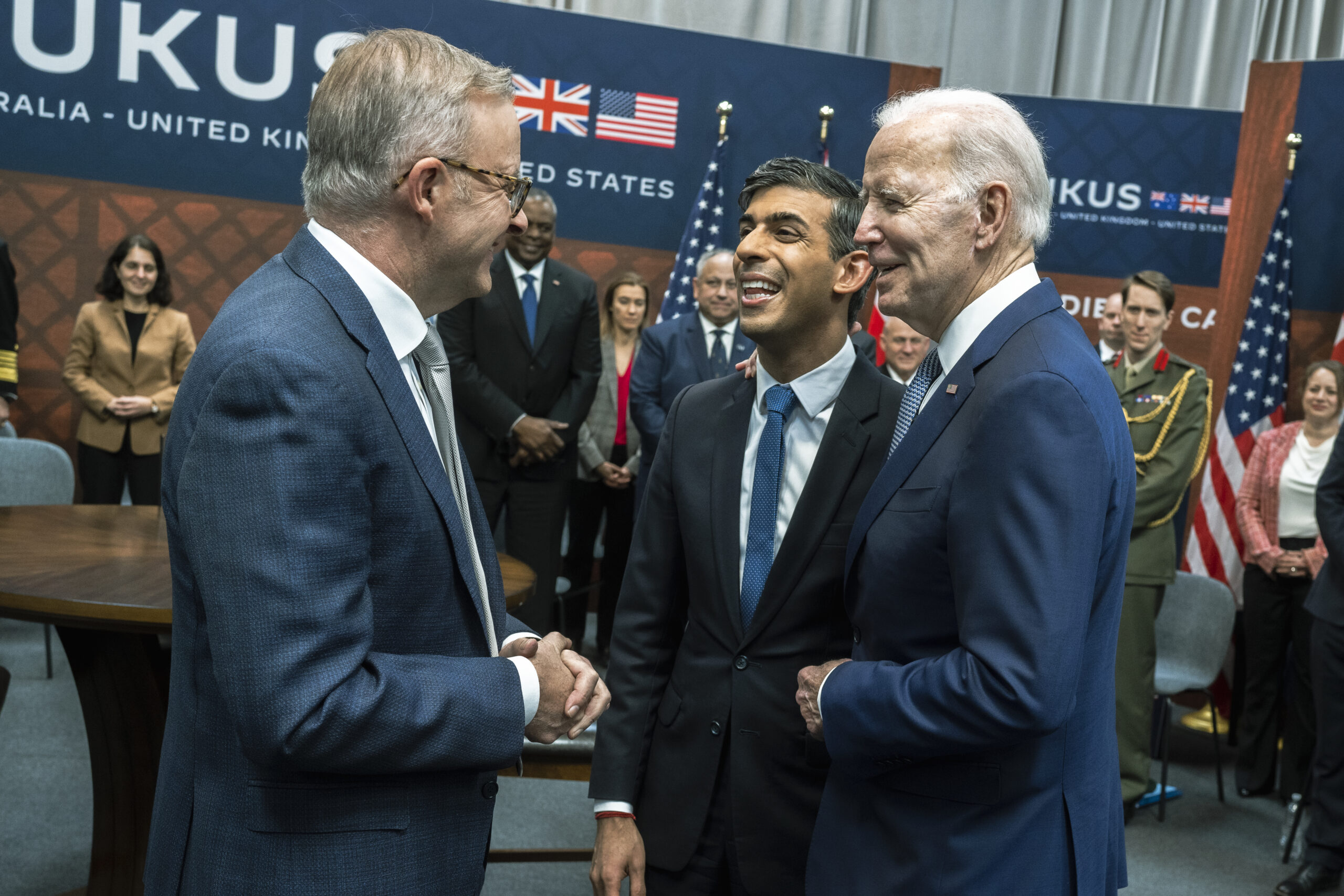

The other major ongoing collaboration that gets much attention is the new ‘AUKUS’ trilateral security agreement between Australia, the UK, and the USA. Although all partners have various forms of longstanding bilateral and multilateral security cooperation agreements already, AUKUS represents a regeneration and repackaging into a trilateral arrangement. It does not involve intelligence collection and sharing, as this is already covered by the long-standing Five Eyes agreement. AUKUS also demonstrates a resolve by its members to confront the geopolitical threat posed by China. For the US, which has always had a security focus in the region, it is a modest readjustment of resources and intent. For the UK, it’s a reassertion of interest in a region where British interests have long been a tertiary concern.

The most prominent component of AUKUS is the Australian attack submarine programme, which was analysed in detail in this magazine in April 2023. The US and UK will share sensitive nuclear propulsion technology with the Australians, allowing Australia to field submarines with much longer endurance. The ability of Australia to project power in the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean region is currently hampered by the operational radius and endurance of Australia’s existing diesel submarine fleet. In the near-term, Australia will purchase Virginia-class submarines from the US. Longer-term, the Australians will work with Britain to develop a new Australian SSN based on existing British designs. It should be noted that this submarine plan has seriously discomfited the French as the AUKUS agreement brought Australian cancellation of an earlier submarine deal with France.

Credit: US DoD/Chad J. McNeeley

The submarine deal and the concomitant political drama with France have taken the lion’s share of the publicity with the AUKUS agreement. However, there are other components in this agreement that might yield promising developments. The agreement promotes cooperation in cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, quantum technology, and autonomy.

Developments or breakthroughs in any of these areas could be significant. Another plank of the AUKUS agreement includes work on hypersonic systems. This is an area with ongoing US-Australian work in the form of the SCIFiRE cruise missile programme. Perhaps this is a portent of British entry into that project, or at least some comparable British benefit.

Money Matters: Procurement

Like many long-standing relationships, issues involving money can be the most tendentious. Britain’s tendency to under-invest in defence annoys many in Washington. This correspondent can almost guarantee that, if his old Pentagon building pass was re-instated, it would not take long to hear some quiet grumbling. The murmuring would be about the UK not investing enough in defence and letting its capabilities atrophy. There will be much lament about Britain being very respectable and having high quality forces, just not enough of them to make much difference in many conflict situations. Britain spends less on defence as a percentage of GDP, than the USA – as do many NATO allies. Fairer ‘burden sharing’ has been, and likely will be, a permanent talking point from Washington.

Credit: BAE Systems

Some of this criticism is honest and fair, as Britain has, objectively, less warfighting capacity in many areas than previous years. Its capabilities and capacity have shrunk in many ways, and the Pentagon is right to worry about that. Yet some of this is also economic angst. The subtext below concerns for defence often has a component of “the UK needs to spend more and more of what they spend needs to come to US companies.” Few will say that quiet part out loud. The US wants the UK as a market for its defence sector.

The UK wants the US as a market for its industry as well. Defence procurement makes for both competition and cooperation. The major manufacturers and contractors have significant footprints in the other country. Some percentage of the US defence budget will support jobs in the UK and vice versa. However, with the perennial weakness of the UK’s overall economy, one suspects that this burden-sharing issue will not go away any time soon.

The symbiotic relationship could be made smoother. A recent House of Commons Defence Committee report on 13 June 2023 spelled out the UK concerns in uncharacteristically blunt words. “Regulatory and bureaucratic constraints provide significant barriers to our ability to collaborate bilaterally between the UK and the US, negatively impacting the UK-US defence industrial partnership.” It only takes a few hours at a defence trade show before one hears complaints about export control regulations hampering collaboration between American and British governments and companies. Additionally, protectionist policies make it far easier for the US government to procure items made in the USA. Numerous UK firms have had to open America-based subsidiaries or joint ventures in order to satisfy Washington’s rules and regulations. One example of many is the Smiths Detection factory in Maryland. When the US DOD awarded the Joint Chemical Agent Detector contract to Smiths Detection (UK), Smiths opened a factory in Maryland to mass produce the item and employed many US staff.

Specific Friction Points

The US-UK defence and security relationship, while broadly solid, does occasionally have a few cracks showing at the edges. While none are existential threats, various issues do come up from time to time. These can be likened to the occasional spats of an old married couple who, at the end of the day, still love each other but just now and then drive each other nuts.

One generic area of friction that does come up from time to time in UK commentary is periodic sourness over the ‘Special Relationship’ being less special in Washington than in London. Sometimes London gets overly anxious, to the point of being just a bit sensitive to a sometimes-insensitive American partner. More than once, officials from Washington have used words like ‘special relationship’ in public appearances with officials in places like Japan, South Korea, Canada, France, Poland, Mexico, and Ireland. This is a matter of semantics and diplomacy, but given how much UK politics appears to be driven by newspaper headlines, the slightest lack of calibration of a remark has been known to cause trouble.

Two interrelated issues that occasionally rear their heads and intrude into the US-UK relationship are Brexit and Northern Ireland. Britain’s exit from the European Union has caused many problems and reaped few benefits. The Brexit spill-over into Anglo-American relations has not yet been fully measured, nor have the defence and security ramifications emerged in full. However, the informal consensus in Washington may be leaning towards the notion that Brexit was a poor idea in both conception and execution. It may eventually make the UK a less compelling base for the European or EMEA outposts of American corporations. Brexit will continue to harm the UK economy and has likely reduced the ability of the UK to buy US defence goods, both through budgetary contraction from the weakened overall economy, and from a loss of buying power through a decline in the value of Sterling.

Credit: USMC/Lance Cpl. Tyler W. Stewart

Northern Ireland is intricately intertwined with both the Brexit issue and the United States. America worked hard to achieve the Good Friday Agreement. This effort was rightly seen as a great foreign policy achievement and the USA often views itself as a guarantor of the agreement. There are millions of Irish Americans, and their views and votes are not inconsequential in US elections. On the other hand, the UK’s land border with the EU is in Northern Ireland. Trying to manage Brexit, Northern Irish political dynamics, and the land border issues, while not breaking the Good Friday Agreement has been a very difficult task.

Adding the American dynamic into it only makes it harder. Current rhetoric about the UK government wanting to exit from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) will further complicate affairs. The Good Friday Agreement requires ECHR membership in Northern Ireland and the UK cannot have one part of the country under the ECHR and one part not under it. This would be an obvious point made by American diplomats and politicians.

The Future

Whatever cracks exist in the US-UK relationship, we must remember that they would be cracks in a fundamentally solid foundation. The US-UK ‘special relationship’ has weathered challenges in the past and will endure future challenges. Nothing we have seen so far is an actual threat to the underlying relationship, which has been good far more than it has been troubled. Furthermore, current and future projects such as F-35 and AUKUS will combine with daily cooperation on more routine matters to buoy the ‘special relationship’ through most problems.

Dan Kaszeta