Plans are afoot in the United Kingdom to revitalise the country’s dedicated military communications satellites with the latest addition to the Skynet family.

The United Kingdom entered the club of nations possessing dedicated military communications satellites in 1969. That year, the UK Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) Skynet-2B satellite reached the heavens. This was not the country’s first attempt. Her first two such spacecraft, Skynet-1A/B launched in 1969 and 1970 respectively, suffered problems.

Skynet-1A failed after circa 18 months of operation and Skynet-1B experienced the failure of one of its motors. Skynet-2A, launched in 1974, experienced a similar fate when its circuits developed electrical faults. It managed just five days in orbit before being deliberately de-orbited and incinerated in Earth’s atmosphere. The MoD finally got things right with Skynet-2B. Also launched in November 1974, this satellite provided coverage over Africa, much of Asia and Europe. Skynet-2B enjoyed over two decades of service.

Plans to replace it with the Skynet-3 constellation were scuppered by the British government’s decision to withdraw from UK major military bases east of the Suez Canal in the late 1960s/early 1970s.

Net Gains

The Skynet-4 satellites were designed with three X-band (7.9-8.4 GHz uplink; 7.25-7.75 GHz downlink) and two Ultra High Frequency (UHF; 305-315 MHz uplink; 250-260 MHz downlink) transponders. X-band Satellite Communications (SATCOM) are reserved for the military use by the International Telecommunications Union. Known as the ITU, this United Nations body governs global use of the radio spectrum. The Skynet-4 constellation also included an experimental Extremely High Frequency (EHF) transponder working on frequencies of 43 GHz to 45 GHz.

The next launches saw the first member of the Skynet-4 family, Skynet-4B, reach the cosmos in 1988, followed by Skynet-4A/C both in 1990. Of this trio, Skynet-4C remains in operation carrying X-band and UHF traffic. A further three satellites, Skynet-4D/E/F followed between 1998 and 2001 with Skynet-4E/F remaining in service. They can carry C-band (5.925-6.425 GHz uplink/3.7-4.2 GHz downlink) traffic along with UHF and X-band.

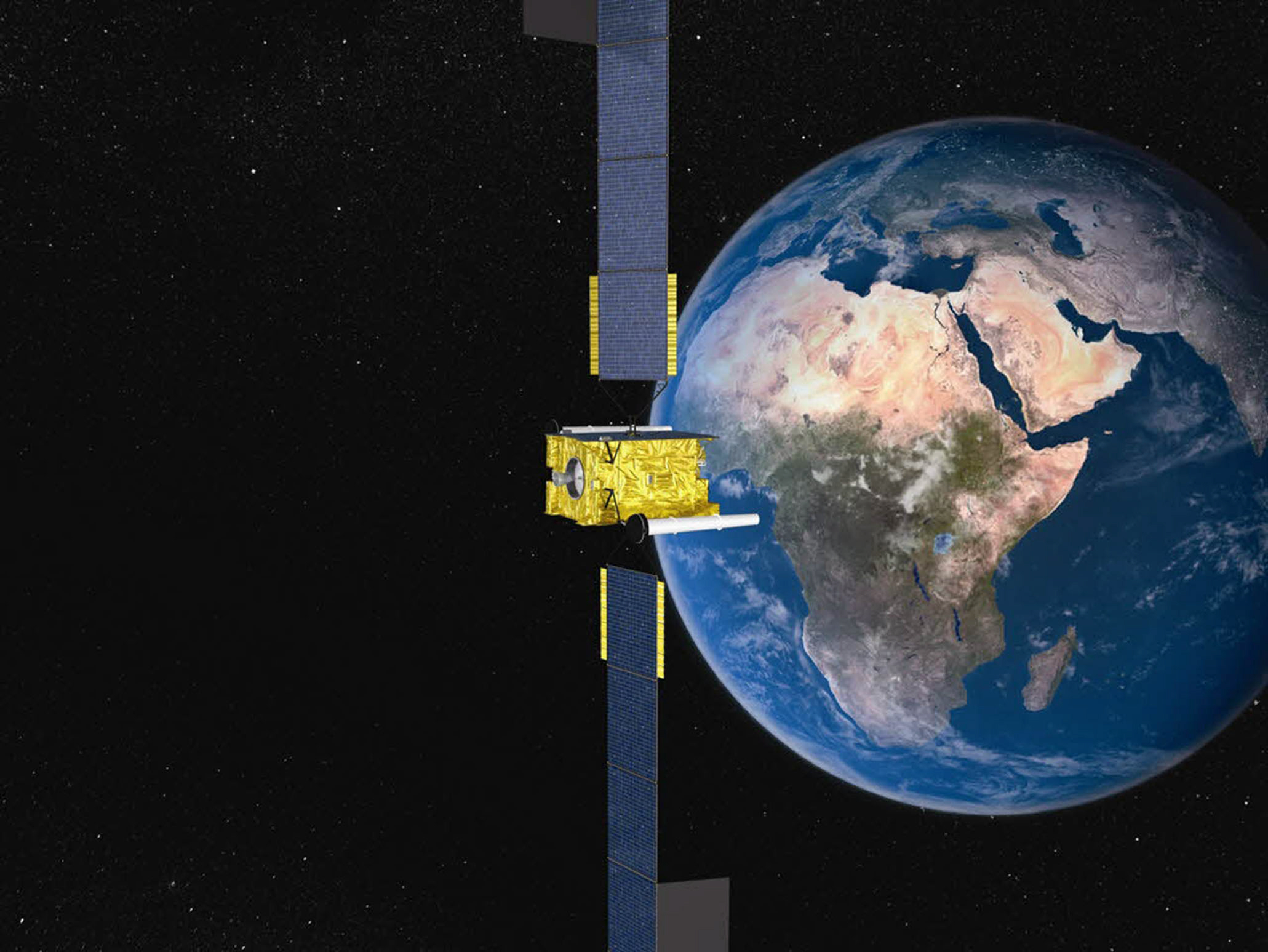

The Skynet-5 constellation are the latest family members. Four spacecraft, Skynet-5A/B/C/D were launched between 2007 and 2012. Equipped with X-band and UHF transponders, they can also handle Ku-band (14GHz uplink/10.9-12.75GHz downlink) and Ka-band (26.5-40GHz uplink/18-20GHz downlink) traffic. Skynet-5 represented a qualitative and quantitative improvement on its Skynet-4 predecessors. Open sources state that each satellite hosts nine UHF channels and 15 Ka-band transponders.

Credit: Airbus

Skynet-5 was procured using an innovative Private Finance Initiative (PFI) approach. Put simply, two companies, Paradigm Secure Communications and EADS Astrium leased SATCOM services to the MoD. EADS Astrium built and launched the satellites while Paradigm provided the SATCOM services. Both companies have since been absorbed into Airbus. The contact allowed Paradigm to sell spare capacity not being used by the UK to other allied nations for military and government communications. Airbus now manages the MoD Skynet contract. It has partnered with other companies, notably Hughes Network Systems, Inmarsat and SpeedCast, with these companies offering third-party Skynet SATCOM services to other customers.

Airbus was contracted by the MoD in 2020 to provide the next Skynet satellite, dubbed Skynet-6A, which is planned for launch in 2025, according to reports. Airbus is constructing Skynet-6A using its Eurostar Neo bus. The contract was valued at USD 736 M in 2023, and covers the construction and launch of the satellites while providing the appropriate improvements to ground infrastructure to operate the spacecraft. Skynet-6A forms part of the UK’s Future Beyond Line-of-Sight (FBLS) SATCOM programme. MoD documents state that FBLS includes the new satellite, in addition to a contract to manage the Skynet constellation supporting elements. This is known as the Service Delivery Wrap. The Skynet-6 Enduring Capability is a separate contract. This covers satellite’s operation and ground infrastructure. The contract also pledges the continued delivery of SATCOM services using the Skynet constellation. The fourth element of FBLS is the MoD’s Secure Telemetry, Tracking and Command (STTC) initiative. STTC provides “assured UK control and management of satellites and their payloads,” according to these MoD documents.

Six Appeal

Skynet-6 will be a further enhancement in SATCOM capacity for the UK. The satellite “will utilise more of the radio frequency spectrum available for satellite communications and the latest digital processing to provide both more capacity and greater versatility than the Skynet-5 satellites,” says Ben Bridge, executive vice president of global business at Airbus’ defence and space division. Bridge emphasises that the spacecraft’s cost effectiveness will be enhanced by using electric propulsion for orbit raising and station keeping.

Electric propulsion uses electromagnetic or electrostatic fields to generate propulsion. This approach uses much less propellant than conventional chemical-based propulsion. The trade-off is that electric propulsion produces a weaker thrust than its chemical counterpart, but nevertheless produces thrust for a longer duration. Airbus would not be drawn on the frequencies that Skynet-6 will handle, nor its bandwidth capacities. That said, Bridge said the company has “designed and is building a satellite that will provide enough bandwidth for the future shape, size and requirements of the (UK) military around the world for the next 20 years.”

Credit: UK MoD

The absorption of Skynet-6 into the UK’s existing Skynet architecture should be relatively painless. The new satellite is designed to “fully support all existing Skynet-5 assured military satellite communications terminals and services, and those already in use by NATO and other allies,” said Bridge. He added that Skynet-6 is on track for a planned launch in 2025.

Show Me the Money

The Skynet constellation (comprising the existing satellites and Skynet-6A) could work alongside the UK’s OneWeb satellites within the FBLS initiative. In 2020 the British government purchased 45 percent of the OneWeb SATCOM company. The firm had gone bankrupt in 2020 but had aimed to build a constellation of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites to provide global, broadband internet coverage. LEO satellites typically use orbits of below 1,000 km (540 NM) above Earth. In July 2020, the Financial Times reported that there was potential scope to combine OneWeb’s and Skynet’s services for military and government use.

One major change that FBLS brings is the end of the PFI model hitherto used to provide Skynet SATCOM services to the MoD. Writ large, PFIs were seen as giving bad value for money to British taxpayers. As David Todd, an analyst for Seradata Space Intelligence wrote back in 2017, many long-term PFIs had paradoxically led to increased costs for governments and poor service. Moreover, existing contractors had sometimes sold on the contracts to new contractors netting themselves a handsome profit. This was ironic as the logic of PFIs was to reduce government debt and have the private sector share some risk in providing major infrastructure projects. For example, a private company would build and operate a hospital, but the government would pay the company for it to provide services to the public.

“At first PFIs seemed to be a good idea,” said Todd in an interview with ESD. “They put the onus of risk onto the manufacturer/service supplier and kept debt off the government’s books. However, examination of their costs, effectively a leasing cost, made many PFI contracts look very poor value compared to a straight commercial loan. Worse was that the poorly designed, very costly service contracts were often sold on to third parties, resulting in the quality of service going down.” Ironically, “it is said that the only PFI that worked satisfactorily was for Skynet-5 where a good service was apparently delivered to the MoD. It also allowed the then Paradigm service company to sell spare capacity onto other allied militaries.”

Nonetheless, Todd underscores the high cost of the PFI compared to a more conventional procurement vehicle: “With respect to the cost-effectiveness of the PFI contract, the overall cost was USD 4.6 Bn compared to a standard purchase contract of say USD 2.5 Bn to USD 3.1 Bn.” The latter is his estimate for construction and launch of four specialist communications satellites plus 15 years’ operation. “Nevertheless, despite the MoD apparently being over a billion pounds worse off, both sides appeared to be happy, albeit with some concerns that some space specialist MoD staff had been poached for the programme.”

Credit: Airbus

“In truth the Skynet-5 PFI contract was never fully tested,” Todd argues. “What would have happened if one of the Skynet-5 satellites had failed or been lost on a launch for example? Insurance payouts, which were possible as this was a ‘commercial’ operation, would have covered the construction and launch costs but probably not any service interruption … Having lost a satellite one suspects that the service provider might have struggled to achieve its service targets for several years.”

Although the Skynet PFI was judged to have been well-managed, hiving off the provision of military SATCOM to the private sector led to much of the MoD’s internal military SATCOM expertise atrophying. Instead, FBLS will follow a more traditional approach. The ministry will own the satellites and supporting infrastructure, but the private sector operating this on the Ministry’s behalf. Instead, the PFI will be replaced by the Service Delivery Wrap. In February 2023 Babcock won this contract, worth USD 497.4 M, which will run from 2024 until 2030, according to the MoD.

LEO Say Yeah!

Where do things go beyond Skynet-6A? A November 2021 report in Battlespace stated that work on the Skynet-7 constellation could begin in the mid-2040s. The report continued that a further three Skynet-6 satellites could join the first of the constellation. One also should not forget the potential role that OneWeb could play. Since SpaceX’s StarLink SATCOM network has been deployed to Ukraine, the deployment has underscored the value of LEO SATCOM to militaries and governments. Looking to the future, one can envisage the Skynet constellation being used for the carriage of highly sensitive and secret traffic. OneWeb could be employed for the carriage of less sensitive information. The latter is likely to constitute the bulk of the traffic on any military SATCOM network. Work continues apace regarding OneWeb. The company said via a January 2021 press release that it planned to have a fleet of 648 satellites in orbit by the end of 2022. As of March 2023, 584 of these satellites were in orbit. The company says that 588 spacecraft can provide global coverage, but that additional satellites are needed for redundancy. By May 2023, OneWeb had confirmed that a total of 648 satellites orbiting. Each weighing 150 kilograms (330 pounds) they provide Ku-band and Ka-band links.

“There is a move away from having a few very vulnerable large satellites to using a LEO-type constellation with lots of spacecraft which have less vulnerability to individual anti-satellite attacks,” observes Todd. “OneWeb will probably be independent in its operation/service vis-à-vis the Skynet constellation as there are no intersatellite links with Skynet as such.” Nonetheless, LEO satellites have the benefit of a lower latency (signal delay) compared to satellites further away. That said, it is important to remember that “LEO systems might be more prone to debris strikes and could even add to this problem.”

MDI Gets High

The coming years will see the UK MoD needing all the communications bandwidth it can get, and this includes SATCOM bandwidth. As they do now, the United Kingdom’s armed forces will continue to deploy around the world. This global footprint requires global, secure communications of the sort that can only realistically be achieved using government-owned military SATCOM. However, the geographical reach is only one driver for this demand, the changing nature of war is the other.

Credit: Google Earth

The philosophy of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) emerged in the United States’ defence community in 2019. A US Congressional Research Service report published in 2022 defined MDO as “the combined arms employment of joint and army capabilities to create and exploit relative advantages that achieve objectives, defeat enemy forces, and consolidate gains on behalf of joint force commanders.” Why should the US military drink the MDO Kool-Aid? Arguably because, “employing army and joint capabilities makes use of all available combat power from each domain to accomplish missions at least cost.”

As the she did with that great US export of rock and roll in the 1950s, the UK has put her own spin on MDO. This has resulted in the emergence of the UK Multi-Domain Integration (MDI) doctrine. This “is about ensuring all of defence (armed forces, government, industry and associated organisations, henceforth known as assets) works seamlessly together, and with government partners and our allies, to deliver a desired outcome,” according to the MoD. These two approaches are merged in the author’s own combined MDI and MDO definition which stresses the interconnectivity of all assets at all levels of war (tactical, operational and strategic) across all domains (sea, land, air, space and cyber). The point of these MDI and MDO approaches is to facilitate decision-making and action at a faster pace than one’s adversary to achieve mission advantage and success.

What does this have to do with the UK’s military SATCOM posture? Quite a bit. MDI and MDO places a premium on connectivity because of the need to knit all these assets together. SATCOM, alongside conventional radio and telecommunications, will play a major role. This is a role which will only grow in importance year-on-year, as the UK’s appetite for data to make rapid, informed decisions grows. To put matters in perspective during 1991’s Operation Desert Storm to evict Iraq from Kuwait, the entire US military deployed into the Kuwait Theatre of Operations had a total of 99 mbps of SATCOM bandwidth available.

Ten years later, this provision increased to 3,200 mbps. This increase directly benefitted the US-led operations Enduring/Iraqi Freedom commencing in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003 respectively. A single US Air Force Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk series unmanned aerial vehicle needs 500 mbps of bandwidth to perform a mission. This is a 405% increase on the 99 mbps bandwidth available to all US forces during the Persian Gulf War. True, the UK’s military is smaller than the US armed forces. However, like the US military, the UK’s armed forces embrace technology and defence digitisation as war-winning capabilities. Future SATCOM bandwidth demands are likely to be as proportionally high in the UK as they are in the US. Military SATCOM capabilities like Skynet-6 and OneWeb will have their work cut out. After all, the need to move torrents of data across vast distances shows no signs of abating.

Thomas Withington