Marking the return of high-intensity conflict, the war in Ukraine has exposed the long-overdue need to invest in land fires capabilities.

In Europe, short-term needs can be identified in the assistance instruments designed for Ukraine, such as the ‘European Peace Facility’ financing the provision of 155 mm artillery rounds and, if requested, missiles. Short to medium-term needs can be deciphered in the ‘Joint Communication on the Defence Investment Gaps Analysis and Way Forward’ issued by the EU Commission and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy in May 2022.

The investment gaps analysis, resulting from a coordinated effort between the EU Commission and the European Defence Agency (EDA), reveals among the “most urgent capability gaps” the need to replace existing Soviet-era legacy systems still in use within EU armed forces with modern European solutions, including heavy artillery. Among strategic medium- to long-term capabilities, the analysis and Joint Communication proposes to work on modernisation of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems in the Air domain, and “combat support, notably a wide range of anti-tank and artillery systems, with an emphasis on precision strike and counter-artillery”, in the Land domain.

The Joint Communication was followed in July 2022 by the EU Commission’s proposal for a ‘European Defence Industry Reinforcement Through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA)’, expected for adoption in September 2023 after intense political negotiations. EDIRPA incentivises common procurement by the EU Member States of the most critical and urgent defence products and will likely have a total budget of EUR 300 M, as the result of the political agreement between the European Parliament and the Council of the EU indicates.

Conflict in Ukraine

Like many other capabilities, the acquisition of future fires is likely to be an integral part of emerging concepts, notably Multi-Domain Operations (MDO). MDO seems to mean “different things to different nations” according to LTC Jose Diaz de Leon from the NATO Joint Warfare Centre who explained how the complex concept of MDO can be understood in the NATO context.

Despite variations of interpretation, a common but less noticed aspect appears in several official publications, starting with the ‘U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028’ released in December 2018 and considered to be among the originators of the concept. This common aspect is a differentiation between “below the threshold of armed conflict” or “competition”, and “armed conflict”. The transition between the two states can happen very quickly, and requires commensurate capacity of swift response. This distinction can also be found in the UK ‘Joint Concept Note 1/20 on Multi-Domain Integration’ published in November 2020, or other NATO members’ MoD publications, for example, the Norwegian ‘Military Advice of the Chief of Defence 2023’.

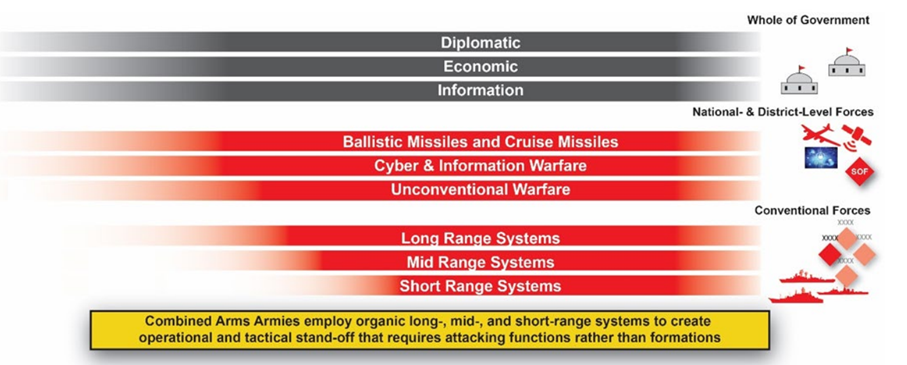

As the ‘U.S. Army MDO 2028’ highlighted, three years before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, revisionist powers such as Russia or China attempt(ed) to create multiple layers of stand-off to achieve their goals. During the state of “competition”, aiming to “win without fighting”, stand-off is sought without resorting to armed conflict by “fracturing (US’s) alliances, partnerships and resolve” through the use of diplomatic and economic actions, as well as unconventional and information warfare.

Threatened employment of conventional forces is also used to achieve goals during competition, and even actual employment of them. During the state of armed conflict, physical stand-off is sought “by employing layers of anti-access/area denial systems (A2/AD) designed to rapidly inflict unacceptable losses (…)”.

During the last two decades of counter-insurgency operations, air superiority was relatively unchallenged and operational approaches were time-phased, domain-federated, and thus predictable. The ‘U.S. Army MDO 2028’ points to the fact that this predictability had become a vulnerability which could be exploited by the opponent by creating layers of A2/AD systems which can (physically) separate the elements of the Joint Force in time, space, and function.

Russia’s stand-off approach is explained as having three layers: whole of government, national and district level forces, and conventional forces. Its elements are visible in fig 1.

Russia’s – and, for that matter, any adversary’s – long-range fires capabilities present a particular challenge because, with these, the ‘support areas’ of their opponent’s battlefield can be targeted. Support areas can cover forward postured forces, prepositioned equipment and stocks, but also – with sufficient range and precision – military land, air and maritime infrastructure and maintenance hubs, and civilian infrastructure.

Advanced mid-range radars and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), capable of integration with long-range systems, are thought to pose a significant threat in the ‘U.S. Army MDO 2028’. Employment of massed tube artillery and multiple rocket launchers (MRLs) could destroy friendly ground forces before these have time to close with enemy manoeuvre forces. Mid-range fires are all the more enabled by networked multi-domain reconnaissance forces that are deployed in depth, for example, ground observation teams, unmanned aerial vehicles, radars, and signal intercept units.

Mid-range systems thus help to create a stand-off which allows ground manoeuvre forces to occupy terrain by using short-range systems. In turn, this enables protection of friendly long- and mid-range fires systems and finding the location of the opponent’s forces for subsequent targeting and engagement with short- and long- range fires.

Re-thinking our Fires Capability Requirements

Far from being a comprehensive description of all elements of the MDO concept, the operational characteristics broadly described above, require a rethinking of capability requirements, including future fires. These should enable deterrence during competition and during armed conflict, they should be integrated at all echelons to enable joint force manoeuvre, including by penetrating and defeating the adversary’s A2/AD systems.

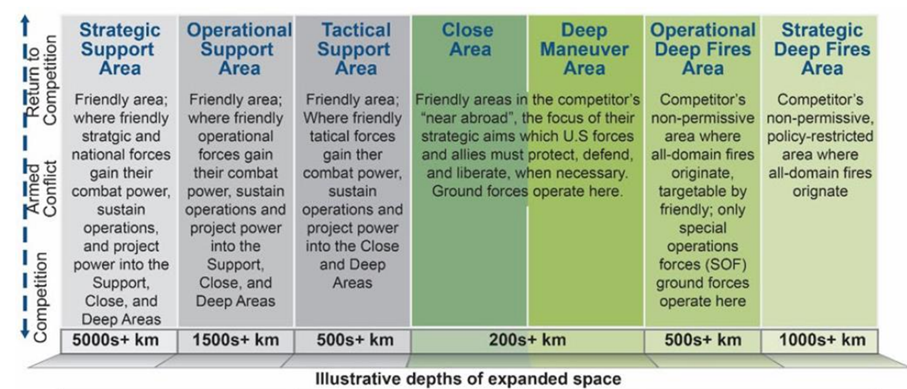

Defining the future role of the fires warfighting function, the ‘US Army Futures Command Concept for Fires 2028’ (AC-Fires) is a useful document to understand related capability needs and technological trends on the basis of the MDO battlefield framework explained in the same document. As mentioned above, the battlefield is expanded into support areas due to the availability of long-range fires capabilities.

AC-Fires considers a broader space by seeing the traditional deep, close, and rear areas of the battlefield at more granular levels, which helps to better illustrate the distribution of friendly and adversary forces, as well as where and how they may employ capabilities, as shown in fig 2.

According to AC-Fires, army fires must facilitate deterrence during competition and, in armed conflict, integrate and employ fires at all echelons throughout the depth of the MDO battlefield framework. As can be seen, the depth can vary between 0 km and 1,000+ km. An obvious need that emerges is the ability to increase and adapt the range of the fires. Since massed fires can be extremely resource-consuming, leading quickly to the depletion of stocks without necessarily hitting high-value targets, achieving precision appears as a second obvious need.

An underlying need besides extended range and precision is the capacity to reach the target at increased speed, to create surprise and deny the enemy sufficient reaction time. The most illustrative example, widely recognised and stated nowadays, is the hypersonic threat – notably hypersonic missiles. However, increase of speed is also sought at lower, more tactical levels.

If these are obvious needs on the offensive, on the reverse side of the coin, it is assumed (or demonstrated) that the opponent will have the same offensive capabilities. Therefore, a complementary obvious need, is to invest in layered and in-depth defences. Among these is the capacity to intercept and destroy the offensive fires, which also require adaptation of range, accuracy and speed.

In the multi-domain setting, ground forces should be able to rapidly integrate with forces of other domains (Air, Navy, Cyber, special forces), so the commander can be provided with multiple options to target and strike the opponent. In turn, this provides the joint force the ability to infiltrate and to overwhelm dispersed adversary formations that are assumed to be concealed and to benefit from strong integrated air defences and long-range precision strike capabilities.

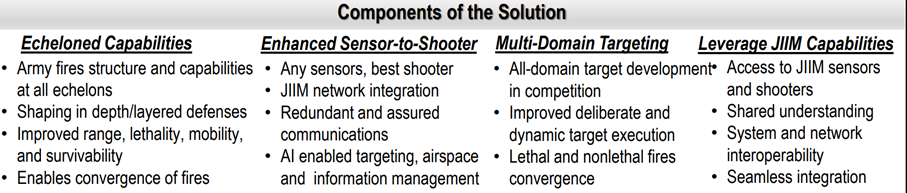

To achieve convergence and create synergistic effects in all domains, AC-Fires proposes a solution for success in MDO that has four components: echeloned capabilities, enhanced sensor-to-shooter linkages, multi-domain targeting (lethal and non-lethal), and leveraged joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational (JIIM) capabilities. Many fires requirements can be derived and understood by simply having a look at the sub-sets of the four components, without further describing or analysing each of them (for description, refer to AC-Fires).

Aside from range, precision and speed, fires requirements in an MDO framework cover a very broad spectrum of enablers that involve a myriad of technology applications, which cannot be detailed in this article. This author will focus here only on what appear to be the most urgent needs and on the latest developments regarding range, precision and speed in the Army component of the Armed Forces. Although being particularly strong enablers for targeting and range, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and loitering munitions are not covered by the article either.

Urgent Requirements: Indirect Fires

As the conflict in Ukraine undeniably shows, acquisition of indirect fire capabilities, both existing and in development, is likely to remain among the top acquisition priorities in the coming years. Indirect fires are essential for the ability to suppress the enemy defences and their offensive systems, thus supporting manoeuvre and advance of friendly forces. Continued support to Ukraine and the need to replenish our own artillery systems and ammunition stocks will fuel procurement demand in this direction, with a corresponding increase of investment in manufacturing capacity.

According to various reports of statements by US Army Undersecretary Gabe Camarillo, the US is expected to increase production of 155 mm artillery shells more than six-fold by 2028. In the EU, the proposed regulation establishing the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) has a similar intent, to support the ramp-up of manufacturing capacities for the production of ground-to-ground and artillery ammunition, as well as missiles. All told, the beginning of 2023 has seen a ramp-up in the procurement of artillery systems.

To address the gap left by donations of AS90 155 mm self-propelled howitzers to Ukraine, the British Army announced in March 2023 their intent to procure 14 Archer 155 mm self-propelled howitzers from BAE Systems Bofors in Sweden as an urgent operational requirement. Additional units are expected to be procured in the following years. The AS90 has an L39 calibre length gun capable of attaining a firing range of 24.7 km.

By contrast, the Archer has an L52 calibre length gun, allowing it to attain greater ranges – 30 km with ordinary High Explosive (HE) projectiles, around 40 km with high explosive, extended range (HEER) base bleed (BB) projectiles, and up to 50 km with M982 Excalibur extended-range GPS-guided projectiles. The manufacturer has also stated that Archer needs “less than 30 seconds from the time the operators receive a call for fire, to stop the vehicle, position for action, and fire the first round”.

In April 2023, Israel’s Elbit Systems announced the award of a contract worth nearly USD 102 M to supply a battalion’s worth of 155 mm Autonomous Truck Mounted Howitzer (ATMOS) wheeled self-propelled howitzers (SPHs). While ATMOS can be equipped with a range of gun lengths, nowadays it is more typically marketed with the L52 gun, which is capable attaining ranges of 40 km with 155 mm Extended Range Full Bore – Base Bleed (EFRB-BB) ammunition.

In July 2023, a USD 150 M contract was announced for the supply of Precise and Universal Launching Systems (PULS) rocket launchers and a package of precision-guided long-range rockets. Both contracts are said to be with an undisclosed international customer, thought by many to be Denmark. PULS can launch unguided rockets, precision-guided munitions and missiles with an effective range of up to 300 km, and according to the manufacturer, as a future growth feature, it could support the capability to launch Elbit Systems’ Skystriker loitering munition.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, similar efforts to replace donations or simply reinforce existing capabilities were made by several NATO countries including France, Germany, Poland and Romania. The experience of Ukraine also reinforced the need for fires that are connected and complementary. In its war with Russia, Ukraine has had to use a myriad of indirect fires systems, a reflection of the diversity of systems in use with NATO countries. As future operations are more likely to happen in a JIIM environment, system interoperability and interchangeability of ammunition are paramount to enabling real-time coordination of fires.

The provision to Ukraine of the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) and of the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) launchers, along with their associated munitions, clearly demonstrated the difference that precision and improved range can make to disrupt high-value targets, such as enemy logistics or command and control (C2) nodes. This has helped Ukraine fight deeper into its opponent’s operational area, thereby encouraging Russia to station high-value command posts and munitions caches further back, outside their range.

Availability of these systems and of the M982 Excalibur precision-guided projectile should help achieve a better balance between, massed fires, which are needed to disrupt the enemy’s confidence and prevent them from grouping up (and also to keep costs down), and precision fires, which are needed to strike high-value targets, in order to degrade the enemy’s ability to resupply and coordinate. The use of precision-guided munitions should also make Ukraine less dependent on massed fires using unguided rounds, thereby slowing the rate at which they burn through ammunition stocks. The following months will probably also show what tactics the Ukrainian Armed Forces are using to maximise the benefits offered by these capabilities.

Beyond Ukraine: Increased Range, Greater Speed, More Precision…

Achieving increased range and more precision is a stated goal in the acquisition plans of many countries, and part of ongoing development efforts.

Notably, for a number of years now, the US Army Long Range Precision Fires Cross Functional Team (LRPF CFT), part of the Army Futures Command, has been developing a portfolio of prototype systems among which:

The Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) – a short-range ballistic missile developed by Lockheed Martin, designed to engage threats from a minimum range of 60 km, out to a maximum range of 499 km. This maximum range figure is understood to have been for compliance with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, however, since the US withdrew from the treaty on 1 February 2019, there would be no legal reason to keep this range limit in future variants of the missile.

Indeed, Lockheed Martin have stated that the missile’s open architecture ensures that “capability can be easily spiraled to achieve longer ranges”, and according to the US Army Acquisition Support Center, follow-on spiral development will focus on attaining increased range, lethality, and the capability to engage of time-sensitive, moving, hardened, and fleeting targets. PrSM is due to enter service in late-2023, and set to gradually replace the US Army’s current inventory of Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missiles.

PrSM will be launched from the M270A2 MLRS and the M142 HIMARS, and due to the missile’s smaller diameter compared to ATACMS, two missiles can fit in each launch pod (as opposed to the one per pod for ATACMS), allowing two per M142 HIMARS launcher, or four per M270A2 MLRS launcher.

The British Army indicated their intention to join the US PrSM programme in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed in 2022 between representatives of the US and British Armies.

- The Autonomous Multi-Domain Launcher (AML), a mobile and transportable launcher that can be deployed, manoeuvred, and fired remotely – a particularly useful asset in A2/AD MDO scenarios. Considered to be ’the autonomous HIMARS’, AML will be both compatible with current munitions and, due to its planned capability to fit a longer launch pod, will also be able to mount longer missiles than fit on the current HIMARS. It is unclear when the AML will become fully operational.

- The Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA), an upgrade to the M109A7 self-propelled howitzer was designed to achieve greater lethality, precision and survivability through extended range and increased rate of fire. ERCA was planned for fielding in 2023, however, according a statement by Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth reported by National Defense magazine in June 2023, engineering challenges were identified, which have delayed the programme’s schedule

In the UK, the recent procurement of Archer is seen as an intermediary step between the AS90 and the eventual results of the Army’s Mobile Fires Platform (MFP) programme.

According to the British Army’s website, modernised Land Deep Fires is one of the highest capability priorities for the Chief of the General Staff. Under the ‘One Launcher, Many Payloads’ vision, the UK Land Deep Fires Programme (LDFP) aims to deliver an upgraded M270A2 MLRS launcher to be equipped with a suite of missiles, including the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) with a range of 84 km, the Extended Range GMLRS (ER GMLRS), with a range of 150 km, the aforementioned PrSM, and the result of the Land Precision Strike (LPS) programme.

The munition to be used by LPS has yet to be decided, but the British Army’s requirement is for a munition suited to engaging mobile and armoured targets at ranges of at least 80 km. Since moving target engagement would require a seeker for target acquisition and terminal guidance, this is a capability the GPS-guided GMLRS lacks. In addition to these munitions, alternative payloads are being developed through the UK’s Technical Demonstrator 5 (TD5) project.

In continental Europe, cooperation between the EU Member States, including via the European Defence Fund (EDF), seeks to achieve similar objectives regarding range, precision and speed. For example, the ‘French Military Programming Law 2024–2030’ prioritises air defence through the modernisation of air and missile defence systems. For long-range strike capabilities, the French stock of M270 MLRS, known in French service as the ‘Lance Roquette Unitaire’ (LRU; ENG: Unitary Rocket launcher) is expected to comprise nine units at the end of 2023, and to grow to at least 13 units by 2030 and 26 units by 2035.

Another example is the recommendation by the Norwegian Chief of Defence in 2023 to prioritise long-range precision weapons among the five recommended measures to achieve a scalable strengthening of the Norwegian Armed Forces over the short and long term. Overall, the requirement for increased ranges, greater speed, and greater precision in indirect fires will no doubt endure for many years to come.

Conclusion

Whereas an armed conflict is fully underway in Ukraine, one can assume that a state of ‘below the threshold of armed conflict’, or competition, continues in parallel in other parts of the world and could escalate into armed conflicts of shorter or longer duration, depending on various endemic geopolitical factors.

The times when NATO forces could operate in relatively uncontested environments, where air and naval strikes could easily shape the operational environment, seem to be drawing to a close. Therefore, the employment of current weapon systems and equipment needs to be adapted to the new context, and new systems must be developed with multi-domain operational logic in mind, where interoperability and ability to act in joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational scenarios will be paramount.

Manuela Tudosia