Ukraine’s USV campaign in the Black Sea has demonstrated how uncrewed systems can have critical impact on naval warfare. Western navies and industry alike are taking this lesson onboard in uncrewed system operation and design.

The use of stealth at sea by Ukraine, a country with lesser absolute and relative naval capability has enabled that country to exercise effective sea denial against Russia, a larger naval adversary, in the Black Sea, a region of vital strategic importance to both. The effective development of sea denial capability is what the Ukrainian Navy has achieved in the Black Sea in the Russo-Ukraine war through its use of uncrewed vehicles, especially uncrewed surface vessels (USVs).

The Black Sea is of significant importance to both countries. In a largely land-centric war, it is a maritime region through which Russia, for example, can attempt to flex its muscles to deter other actors from trying to shape the conflict. Operating from key bases at Sevastopol in Crimea and Novorossiysk in Russia, the Russian Navy can use the Black Sea to hem Ukraine in, to conduct land-attack strikes using long-range sea-launched cruise missiles from surface ships and submarines, or to consider amphibious actions along Ukraine’s southwestern coast.

Moreover, Russian naval forces roaming across the Black Sea implementing a naval blockade and conducting extensive mining can make it very difficult for commercial ships to operate there. For example, ships exporting Ukrainian grain under the Black Sea Grain Initiative have – when permitted to sail – been operating at significant risk. With Western naval powers denied entry into the Black Sea by Turkey’s closure (under the 1936 Montreux Convention) of the Bosporus/Dardanelles straits to any warship or submarine not homeported in the Black Sea, in naval terms the opportunity was there for the Black Sea to become a Russian-dominated body of water.

On his open-source intelligence defence analysis website Covert Shores, H I Sutton provides a detailed timeline of events in the Black Sea during the war (with the piece last updated on 14 October 2023). War broke out in February 2022. Sutton noted that, by 3 March 2022, most of the Ukrainian Navy’s warships had been captured, sunk, or scuttled. “Ukraine, whose fleet was massively out-gunned, is left with only a few smaller vessels,” Sutton wrote. Yet, as the saying goes, no plan survives first contact with the enemy.

For Ukraine, the Black Sea also is strategically critical. It has acknowledged laying minefields to keep Russian naval forces out of reach of its southwestern shores. It needs to shape events in the Black Sea to isolate Crimea, for example by targeting the Kerch Strait Bridge with long-range strikes and conducting amphibious raids on Crimea to target Russian surveillance capabilities. Perhaps most important for Ukraine was to stop Russian naval forces from operating in the Black Sea. Certainly, it has succeeded in severely restricting the activities of major Russian Black Sea Fleet assets. It has done so in large part by using uncrewed systems, enabled by stealth technology and tactics, to attack Russian ships and submarines at sea and in port.

The first signs of what would become a significant Ukrainian capability for conducting effective sea denial operations using stealthy, uncrewed systems emerged in late March 2022, when various Russian navy ships were hit at sea and in port. Sutton noted that Russia stopped using the port of Berdyansk, the target of one attack, for resupply. On 13 April 2022, the Russian Navy Slava-class cruiser Moskva – Black Sea Fleet flagship and a central presence of Russian naval operations in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean for many years, was hit by two Ukrainian Neptune anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and sank the next day. It could be argued that the sinking of the Moskva was due to a lack of air-defence capability – as well as a ship technology, readiness, and operational – issue, and not a stealth capability issue.

However, subsequent developments demonstrated that a primary route Ukraine would use to offset its absolute and relative lack of naval numbers and capability was an asymmetric one – deploying stealth capability through the covert use of uncrewed vehicles.

USV Operations

In the maritime domain, Ukraine has mastered the use of uncrewed vehicles in the air, surface, and sub-surface domains – including uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs), uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), and uncrewed underwater vessels (UUVs) – and in a way that has demonstrated to even major Western navies just how much value such capabilities can add, at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels, when used in the right way. This has been particularly true with Ukraine’s USV use.

Credit: NATO

On 21 September 2022, a Ukrainian USV washed up outside Sevastopol. “Russian forces destroy it but otherwise do not appear to react to the new threat,” Sutton noted. On 29 October 2022, Ukrainian USVs and UAVs struck Sevastopol, with the USVs penetrating the harbour, and with the Admiral Gorshkov-class frigate Admiral Makarov (one of Russia’s newest ships, commissioned in 2017) being hit. While no ships were sunk, Sutton said “Russia [withdrew] its fleet into bases and [started] initiating increased defences.”

A month later, a USV attack on Novorossiysk demonstrated that Ukraine could reach right across the Black Sea with its stealthy, uncrewed capability. Novorossiysk is some distance from Ukrainian waters, and Ukraine’s ability to deploy a USV from one side of the Black Sea to the other testified to the evident stealth capability it was developing with uncrewed systems.

Indeed, Sutton noted, while Ukraine has continued with its USV operations, it has continued in parallel with their technological development. Moreover, Russia has successfully defended against some Ukrainian USV attacks – but the fact that the attacks have continued, and in different Black Sea waters, suggests Ukraine also has mastered the mass issue when it comes to USV development.

In July 2023, Ukraine used its USVs to strike the Kerch Bridge: such an attack sent out quite a symbolic message. In early August 2023, the impact of Ukraine’s USV attacks stepped up once more, with successful strikes on the Ropucha-class landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak outside Novorossiysk (significantly damaging the ship, according to Sutton) and on a Russian oil tanker travelling south of the Kerch Bridge.

A mid-September 2023 attack highlighted another element of Ukraine’s evolving USV capability, with an operation involving 10 or more USVs reported to have targeted a Russian tanker and a logistics vessel. This indicated Ukraine’s capacity to launch USV attacks in numbers, offering the potential to generate swarming capability. A day or so later, a further attack followed – this time, Sutton noted, possibly involving two experimental semi-submersible USVs. Ukrainian USV attacks have continued, with Sevastopol targeted again on 13 October 2023.

Operational Impact

Naval platform design – whether of ships and submarines, or of uncrewed vessels – has shifted increasingly over the last two decades towards the use of stealth.

Currently, the development of USVs in this stealth context is seeing them generally designed to support what are known as the ‘6-D’ – ‘dull, dirty, dangerous, dear, deep, and [long] duration’ – tasks, replacing crewed platforms in conducting these tasks to enable those crewed platforms to focus on higher-end missions to which their capabilities are best suited.

The ‘6-D’ tasks focus, for example, on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) to support missions like anti-submarine warfare (ASW) or mine counter-measures (MCM). In the former instance, USVs and other uncrewed platforms can provide sustained presence to provide the required monitoring; in the latter, they negate the need to put crewed platforms in harm’s way. In both contexts, stealth is crucial to ensuring operational effectiveness.

Credit: NATO Maritime Command

At the recent, combined ‘REPMUS’/‘Dynamic Messenger’ maritime uncrewed systems (MUS) exercises, which took place in southern Portugal in September and which are co-hosted by the Portuguese Navy and NATO Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM), uncrewed systems including over a dozen USVs were tested in different operational scenarios, namely ASW, ISR, MCM, and critical undersea infrastructure warfare (CUIW). Detection of uncrewed systems – UAVs, USVs, and UUVs alike – was a priority in several exercise serials. This included setting up a Thales Squire prototype phased-array radar at the exercise hub at Troia to conduct counter-UAV/-USV surveillance. In a separate serial, different MUS types were deployed covertly to provide ISR support for an amphibious landing.

For the assembled senior naval and NATO leaders and staff officer-level subject matter experts (SMEs), lessons learned from the use of uncrewed systems in the Russo-Ukraine war – and especially their asymmetric impact, due to their stealth technology – were right at the forefront of both the strategic-level thinking shaping NATO’s approach to operations and capability development, and the technological and tactical thinking shaping the exercise serials. In sum, such systems are having significant impact on the current evolution of naval warfare thinking and capability development.

“Autonomous systems are changing naval operations. A small of cell of Ukrainian drones is successfully conducting a sea denial campaign in the Black Sea against a much stronger Russian Navy,” Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo, the Portuguese Navy’s Chief of Staff, said in his keynote speech opening the exercise’s Distinguished Visitors’ (DV) Day.

Ukraine’s effective use of uncrewed systems, particularly USVs, is prompting NATO to consider the asymmetric impact of such capabilities in offensive terms, but also how to defend against such capabilities. As regards offensive operations, Ukraine’s campaign has demonstrated how the stealthy use of uncrewed vehicles can provide NATO with another option for achieving disproportionate military effect, alongside simply deploying a large NATO task group. As regards defensive operations, and noting Sutton’s point that Russia too has conducted successful Black Sea USV operations, NATO navies are now having to think about force protection and wider defence against uncrewed systems.

Credit: US Navy

At the exercise, NATO leaders discussed the strategic-, operational-, and tactical-level impacts of Ukraine’s uncrewed systems campaign on Russian Black Sea operations. “If you look at the Black Sea Fleet and its operations, from the outset – before the Ukraine war – you would see that as a potent, expensive capability,” a senior NATO official told a media briefing at the DV Day. “Through the use of capabilities like armed USVs – low profile, difficult to detect – and a good use of UAVs as well, Ukraine has rendered the Russian Black Sea Fleet almost ineffective, in terms of what it was going to do.”

“If you looked at the plans right at the start of the war, you were looking at bombardment in gearing up for amphibious assault from the south etcetera, but now the Black Sea Fleet assets are the other side of the Crimean peninsula, and they don’t come out that often because of the threat,” the official said.

This impact was also achieved using a threat that is “very much asymmetric”, the official added, estimating that Ukraine’s capability investment in uncrewed systems may have been in the order of EUR 30 M.

As regards lessons learned from NATO’s perspective, the official detailed lessons at both the tactical/operational and strategic levels. As regards tactical/operational lessons, the kind of questions NATO must start asking include how to use similar types of tactics, what other tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) might need to be developed to employ such systems, what uncrewed system capabilities might allied countries need to develop, and how might existing and emerging national capabilities be integrated across the alliance.

At the strategic level, the official continued, “The other question we must ask ourselves is how do we defend against that threat? There’s always a need for [Western navies to develop] exquisite capabilities, but how do you protect them against something that’s very difficult to detect?”

“The war in Ukraine has showed us that we need to counter uncrewed systems in all domains. We need to think about how we protect our forces in that sense,” he added. “The type of [USVs] Ukraine is using are very low profile, which makes them difficult to detect at night,” the official continued.

Credit: NATO Maritime Command

NATO and its member state navies have previously used ‘REPMUS’ to test and evaluate what can be achieved with stealthy USVs. In ‘REPMUS 2021’, for example, the Maritime Tactical Systems’ (MARTAC) Mantas T12 USV was deployed. “We used [it] to go into an area covertly with a disruptive payload that would disrupt adversary communications,” the official said.

Designed for Stealth

An overlaying principle for the design of Western naval platforms – crewed or uncrewed – is to implement a stealth design for core elements of the vessel’s architecture, including for example: superstructure design, to reduce radar reflection; communications emissions, to reduce the electro-magnetic signature; and heat emissions, to reduce the optical signature.

Much of the focus on increasing stealth in crewed platforms is to reduce their defensive susceptibility to incoming attacks. This focus has been sharpened by the changing nature of, for example, the missile threat in naval operations, which is now bringing increased anti-ship missile (ASM) capability through range and speed improvements – the latter including the advent of hypersonics.

One difference in naval architectural design considerations between crewed and uncrewed platforms – as demonstrated by Ukraine’s USV use in the Black Sea – may be that the operational concept for using uncrewed systems is based largely on designing in stealth capability to enhance their offensive operational impact.

As noted in Sutton’s analysis, an element of Ukraine’s technology development with its USV capability is to build systems that are stealthy largely because they have a low-observable design with very little superstructure standing out above the surface. This design focus is continuing to the point where Ukraine is now experimenting with semi-submersible USVs.

Semi-submersibles are not a new maritime concept. Industry companies have developed low-observable surface vessels that can transition to submerged operations, meeting special forces insertion requirements. Narcotics cartels have developed low-observable and semi-submersible vessels, as well as ‘mini submarines’. However, these have all been crewed platforms.

Developing and operating low-observable and semi-submersible uncrewed vessels is not something that has been tried much in operational terms until Ukraine’s Black Sea USV campaign. Yet stealth requirements now appear to be an integral design element for USV technology and capability development going forward.

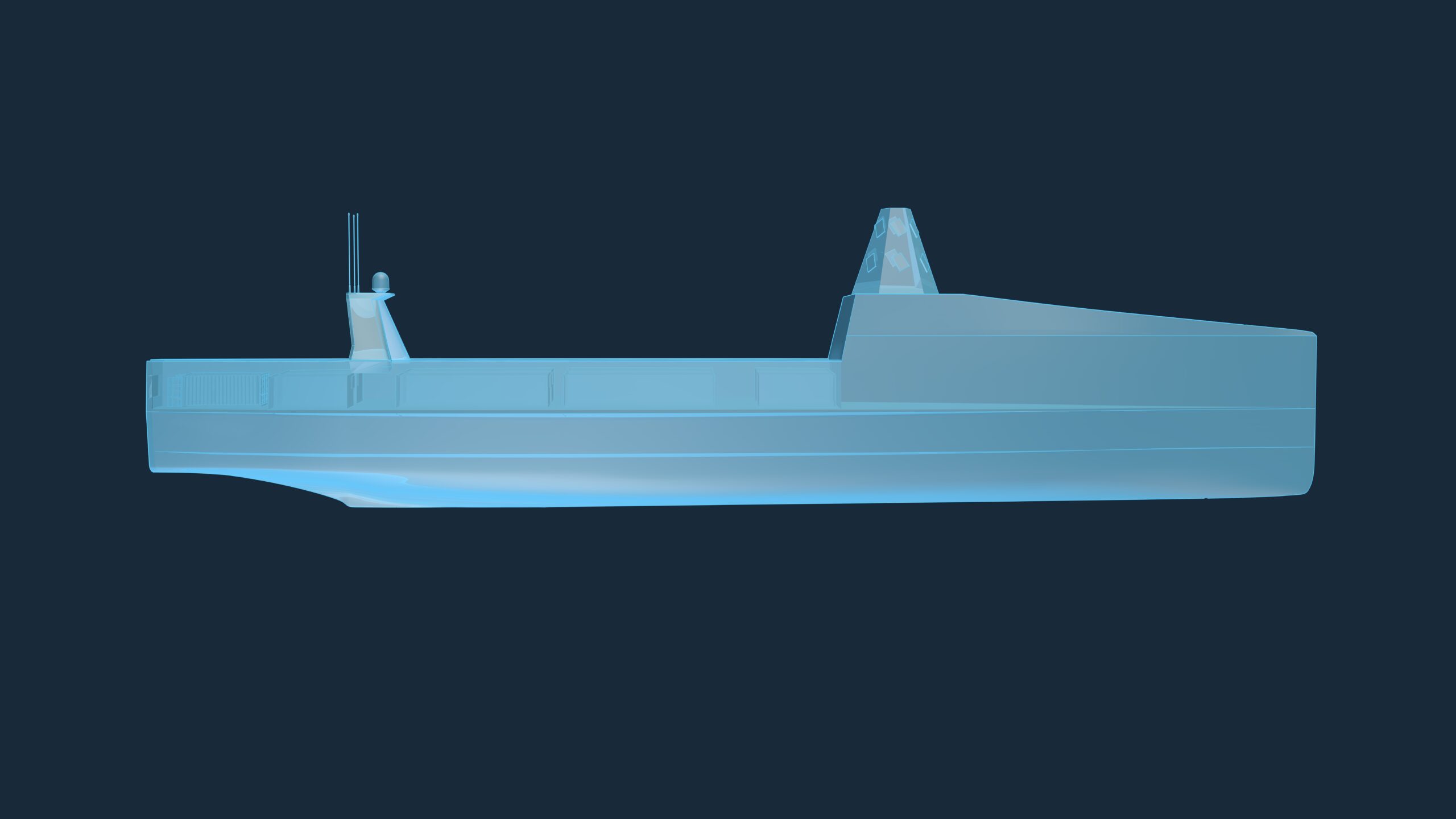

Credit: BMT

Beyond stealth, mass is also a key consideration. For example, at the Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) exhibition in London during September 2023, BMT – a UK-based engineering design house and consultancy that provides naval architecture capability – launched its Large Uncrewed Surface Vessel (LUSV) concept. As set out in a White Paper the company published at DSEI as part of the LUSV launch, central to BMT’s LUSV concept of operations is that such systems can be procured in numbers to generate mass, and can provide significant capability through increased use of autonomy. The White Paper also pointed to an anticipated future operating environment that will include periods of intense operations.

One lesson emerging from the Russo-Ukraine war – and as demonstrated in Sutton’s analysis of Ukraine’s Black Sea USV operations – is that uncrewed systems are being procured, used, but also lost (in combat) in large numbers. The fact that USV attrition rates will be high, as with any asset type in large-scale conventional conflict, makes stealth design increasingly important in reducing risk of detection and loss.

Indeed, BMT’s White Paper underlined the role of uncrewed systems in adding mass in hull numbers to offset attrition rates that can be exacerbated through using uncrewed systems, as has been demonstrated in Ukraine. “A great example of such a rapidly evolving threat environment is seen in Ukraine’s effective use of small maritime surface drones to challenge Russian naval superiority in the Black Sea, conducting damaging strikes on capital ships and military tankers,” the paper stated. “It is threats like this that will need greater numbers of flexible protean assets to counter.”

LUSV concepts may also offer the space, with no human operators onboard, to embark larger weapons payloads, thus bringing mass in firepower too. In discussing how LUSV concepts can contribute to contemporary naval operations, the White Paper highlighted the importance of stealth in LUSV design and capability. This discussion also underlined how the absence of crew can fundamentally change platform design, offering opportunities to develop stealth capability in new ways.

The White Paper pointed out that while modularity in design for LUSVs would enable them to meet a broad range of mission requirements, a core role would be to provide sensor packages to deliver sustained ISR in support of the ‘6-D’ tasks, enabling missions such as protecting critical undersea infrastructure nodes, establishing ASW barriers, or providing an ASW or air-defence picket capability at the outer range of a task group. LUSVs could also be deployed into contested littoral waters, where crewed ships may be considered too valuable and too at risk given the layered defences present. “The LUSV role is still an area to be fully explored, but the starting point is roles that fit the ‘6-Ds’,” Andy Kimber, Chief Naval Architect at BMT, told ESD in a written interview on 23 October.

Nonetheless, the operational-level importance of these role underlines the need for stealth in USV design and technology, to reduce detection and attrition risk. “As USVs will have to rely less on recoverability (as this normally requires some kind of human intervention) and potentially may be limited in their (hard-kill) self-defence capabilities, stealth is likely to be a key feature to minimise detection (or at least suggest minimal value in attacking) and enhance the potential of decoy systems as a form of self defence,” Jake Rigby, BMT’s Head of Innovation and Research, said in the written responses.

To provide such stealth, the White Paper underlined the LUSV design need for a “stealth radar profile (radar cross-section minimised from reduced superstructure – no bridge or accommodation)”. Specifically, it defined the above-water signature for an LUSV as being low-observable in terms of infrared (IR) signature and radar cross section (RCS), and the LUSV’s below-water signature as needing low in-water acoustic noise and low magnetic signature.

Alongside the reduced ‘topside’ profile, with no need for a bridge onboard to provide space for human operators to conduct watch of ship operations, the absence of personnel onboard can also reduce requirements for auxiliary safety machinery, thus reducing below-water radiated noise. Overall, the White Paper assessed, an LUSV’s low signature should be generated by “Focusing on underwater radiated noise and radar cross section”.

Credit: US Marine Corps

As regards the overall concept for enhancing stealth capabilities in an uncrewed platform, “Making the vessel uncrewed has its challenges, but allows you to re-think the whole design layout by removing the normal constraints and limitations,” Rigby added.

Yet, as with any military platform design, a balance must be struck between requirements, outputs, and costs when introducing stealth concepts and technologies. “A key aspiration for uncrewed vessels will be to reduce detectability, to allow their sensors to collect data and reduce the risk of being targeted,” Kimber explained. “However, the degree of stealth that may be applied will have to be judged against ultimate effectiveness and the goal to make such larger USVs affordable enough to achieve the promise of mass.”

“Stealth features will not only reduce a USV’s susceptibility to attack, but will help ensure its sensors and countermeasures can operate effectively,” Rigby continued, adding “but in these cost-sensitive vessels, the features must be carefully considered to ensure benefits are proportional to cost.”

However, when weighing up the impact of stealth upon the cost equation for such cost-sensitive vessels, there is another factor to consider. “Recent conflicts have stressed the importance of cost-effective capability provision,” said Rigby. “Stealth features do not always have to be expensive, as is often assumed. Significant benefits can be achieved through careful design and incorporation of best practice.”

Dr Lee Willett