19 September 2023 marked the start another active military conflict, this time in Nagorno-Karabakh: between the local Armenian troops and Azerbaijan.

Despite lasting only one day, the conflict led to 412 official causalities for both sides and according to the Armenian Government has led to ethnic cleansing – with practically the entire Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, numbering over 100,000, fleeing from the disputed region to Armenia in the days following the clash. The one-day war also surprisingly resulted in relatively high causalities for both sides.

Military Imbalance Eroding the Status Quo

Nagorno-Karabakh started to become a conflict region in 1988, when the local Armenian population started to claim the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous region from Azerbaijan and demanded to join Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR). This process triggered the First Nagorno-Karabakh War of 1992-1994, and ended with defeat of Azerbaijan, which lost control not only over the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous region, but also of seven ex-Azerbaijani SSR regions around Karabakh, most of which provided a land connection with Armenia, which Karabakh itself lacked. A ceasefire was brokered by Russia, but it never was completely fulfilled. Peace negotiations were mediated by the Minsk OSCE Troika (France, Russia and the USA) for many years without result and continued against the background of continuous violations of the ceasefire along the line of contact in Karabakh and even at the Armenia-Azerbaijan border.

The status quo started to deteriorate in April 2016, when the first large-scale hostilities after 1994 started and resulted in small gains on the line of contact for Azerbaijan. This was the result of the military approach chosen by Baku, which became a much wealthier country after 2005, as it began to export of large volumes of fossil fuels amid higher oil prices. This would resulted in changing the military balance between the two countries’ armed forces, since the Azerbaijani defence budget was several times larger than Armenia’s. Baku enacted the large-scale procurement of tanks, artillery, armoured vehicles, air defence assets, combat aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Israel and Turkey starting from around 2005.

Credit: Baykar

A major shift occurred in 2020, during the 44-day Second Nagorno-Karabakh war, where Azerbaijani troops managed to gain a military victory. The 2020 war demonstrated some of the newest components of modern warfare, including the massed use of combat UAVs such as the Bayraktar TB2, and ISR UAVs in combination with artillery and loitering munitions.

Azerbaijani Armed Forces were able to conduct a suppression of air defence (SEAD) operation almost without use of manned aviation, relying on the coordinated actions of uncrewed vehicles. Such success was reinforced with a more modern and creative approach in land warfare: the first failed attempts to undertake a ‘classical’ offensive with tanks and armoured vehicles were replaced with offensives by lighter mobile troops, which were able to disorganise the defending Armenian forces. Many of these modern approaches were taught to Azerbaijani Armed Forces by high-ranking Turkish officers, which Armenia has stated were actively involved in developing and conduction the operation. At the same time, Russian support to Armenia was very limited, despite the two countries being allies.

The war resulted in the Trilateral Statement, made by leaders of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia. According to statement, Azerbaijan gained control over territory of seven regions around Nagorno-Karabakh along with Shushi and Hadrut cities which were part of Karabakh, while Russia established a 1,960 personnel-strong peacekeeping mission which became security guarantor for local Armenians and was in charge of guarding the Lachin corridor – the only road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia proper. Also, the Statement outlined some bases for peace negotiations, including the exchange of POWs, opening of the transport communications between countries, and various others.

This postwar period was stable for only a few months, and in May 2021 Azerbaijan started to re-assert military pressure – now also directly on Armenia, as well as occupying border territories during limited operations. The most large-scale escalation happened on September 12-13, during which the intensity of hostilities was comparable to Second Karabakh war. Azerbaijani troops occupied more than 140 km2 of Armenian territory and conducted artillery and UAV strikes deep into Armenian territory, destroying some air defence assets and damaging Armenian Armed Forces bases. According to official sources, Armenia lost 202 and Azerbaijan lost 80 servicemen in just two days – more than during the 2016 four-day war in Nagorno-Karabakh. These hostilities showed that the Armenian Armed Forces were still not ready to organise an effective defence against Azerbaijan, especially in the sphere of air defence. As a result of the Azerbaijani attack, Armenia negotiated an EU monitoring mission to the border, which was established for 2 years and could be prolonged further.

Against the background of direct Armenia-Azerbaijan tension, Baku also started to put pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh, despite the existence of the Russian peacekeeping mission and security guarantees. The peacekeepers were shown to be very passive, especially after the beginning of Russo-Ukrainian war, which took a much higher priority for Russian military resource dedication, as well as limited general interest to the region. After several local attacks by Azerbaijani troops, which resulted in almost no reaction from the Russians, Baku started a blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by blocking the Lachin corridor in December 2022. This also did not lead to any real reaction from Russia and its peacekeepers. This passivity gave Baku the confidence sure that it could run a final military campaign in Karabakh, which started on September 19 and finished on September 20, 2023.

Success with Surprisingly High Causalities

The launch of hostilities in Karabakh on 19 September 2023 started with massed indirect fires by Azerbaijani troops on military objects and defence infrastructure along the line of contact. Azerbaijani troops used Lora tactical ballistic missiles (TBMs), Harop and SkyStriker loitering munitions, tube and rocket artillery, as well as Spike-NLOS long-range anti-tank missiles. After this, their land forces launched an offensive, planning to cut Nagorno-Karabakh into 3 isolated parts, without entering the large cities, such as the capital – Stepanakert, or Martakert, which was surrounded but not taken. Despite the heavy indirect fire support, Azerbaijani land forces met fierce resistance in most directions and took higher-than-expected causalities. By contrast with their performance in 2020, Armenian forces even conducted several successful drone strikes, using modified civilian multicopters without encountering many counters from their enemy, which seemed unprepared for such actions.

Credit: Elbit Systems

Despite such innovations, the defenders had no chance of winning, as the region was already cut-off from Armenia and the number of troops was quite limited, with contemporary assessments of Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army estimating a strength of 7,000-10,000 servicemen. Alongside this, Azerbaijan’s pre-war 9-month blockade also diminished their fuel stocks, making their defensive and offensive options more limited.

Given this situation, if the war had not been stopped almost immediately by the surrender of Karabakh local authorities, the question would have been how many days it would have last and how many casualties sides would have, but the final result was never in doubt.

Russian peacekeepers did everything to stay out of the conflict, despite that there is evidence of an artillery strike on one of their bases and two cases when Azerbaijani troops opened fire at them. That led to death of six peacekeepers, including Captain First Rank Ivan Kovgan, the deputy commander of Russia’s Northern Fleet submarine forces, and deputy commander of the peacekeeping mission. Following his death, an official apology was made by Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev over a phone call to Vladimir Putin.

The one-day conflict resulted 192 dead and 512 wounded Azerbaijani servicemen, while local Armenian forces reported 220 servicemen dead and 360 wounded. Yet the most grave outcome of Azerbaijan’s offensive was that it resulted in the effective ceding of the self-proclaimed Artsakh Republic to Azerbaijan. Artsakh Republic President Samvel Shahramanyan signed a bill which dissolved the existence of the republic, allegedly with under the condition of threats to both himself and local population. Azerbaijan’s seizure of the region also resulted in the entire Armenian population of the former Artsakh Republic fleeing for Armenia, leading Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to accuse Azerbaijan of conducting the ethnic cleansing of the region. Additionally, several acting and former political and military leaders of the Artsakh Republic were arrested and are being prosecuted in Baku, including an Armenian-origin billionaire from Russia, Ruben Vardanyan, who moved to Karabakh before the blockade of Lachin corridor.

What Next?

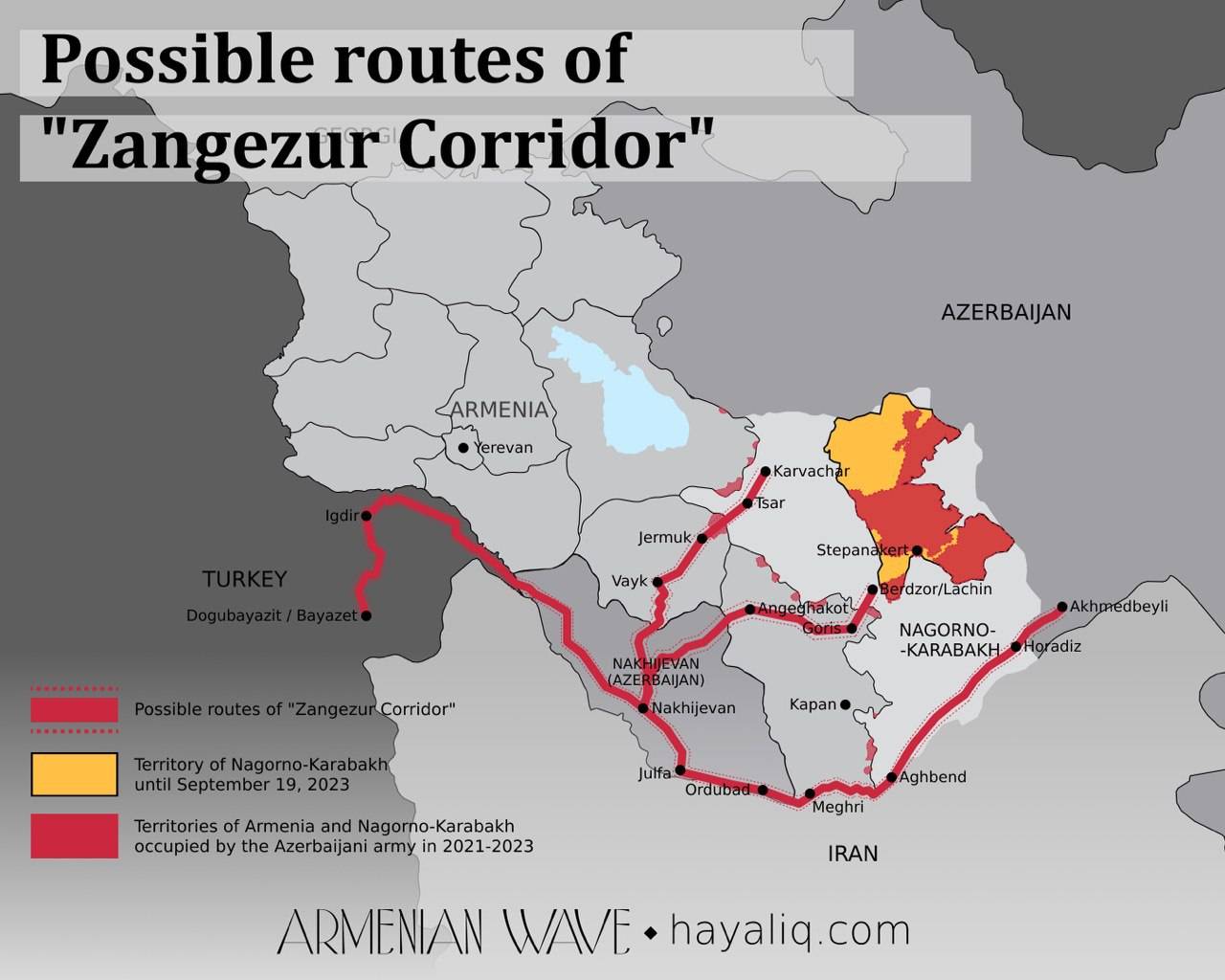

Despite the fact that since 2020 Baku has attained its maximalist goals, and there are no practical obstacles for a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, tensions between the two countries is not decreasing. At present, Azerbaijan is seeking to get maximum possible out of negotiations on opening of the logistical routes between the countries. Based on the point 9 of the Trilateral Statement of 9 November 2020, Baku is demanding a railway and highway with special status, which should pass through Armenian territory and connect Azerbaijan’s mainland with its Nakhchivan exclave. This is known as the ‘Zangezur corridor’. According to the Trilateral Agreement, “The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the safety of transport communication between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic with a view to organize the unimpeded movement of citizens, vehicles and cargo in both directions. Control over transport communication shall be exercised by the Border Guard Service bodies of the FSS [Federal Security Service – more commonly referred to as the FSB] of Russia”.

Credit: Hayaliq/Armenian Wave

Moscow’s interest also lies with this ‘corridor’ idea, as it will provide Russia more on-the-ground presence in Armenia. Yerevan’s position in this case is to simply open the route for Azerbaijanis to go to Nakhichevan via Armenian territory, but with no special status road and no Russian FSB guarding the route in place of Armenian customs officers. This position has a certain logic, since de-facto, none of the ‘pro-Armenian’ points of the Trilateral Statement exist anymore – including security for Karabakh Armenians and the functioning of Lachin corridor, as well as exchange of all POWs – and the agreement has long since been seen as a failure.

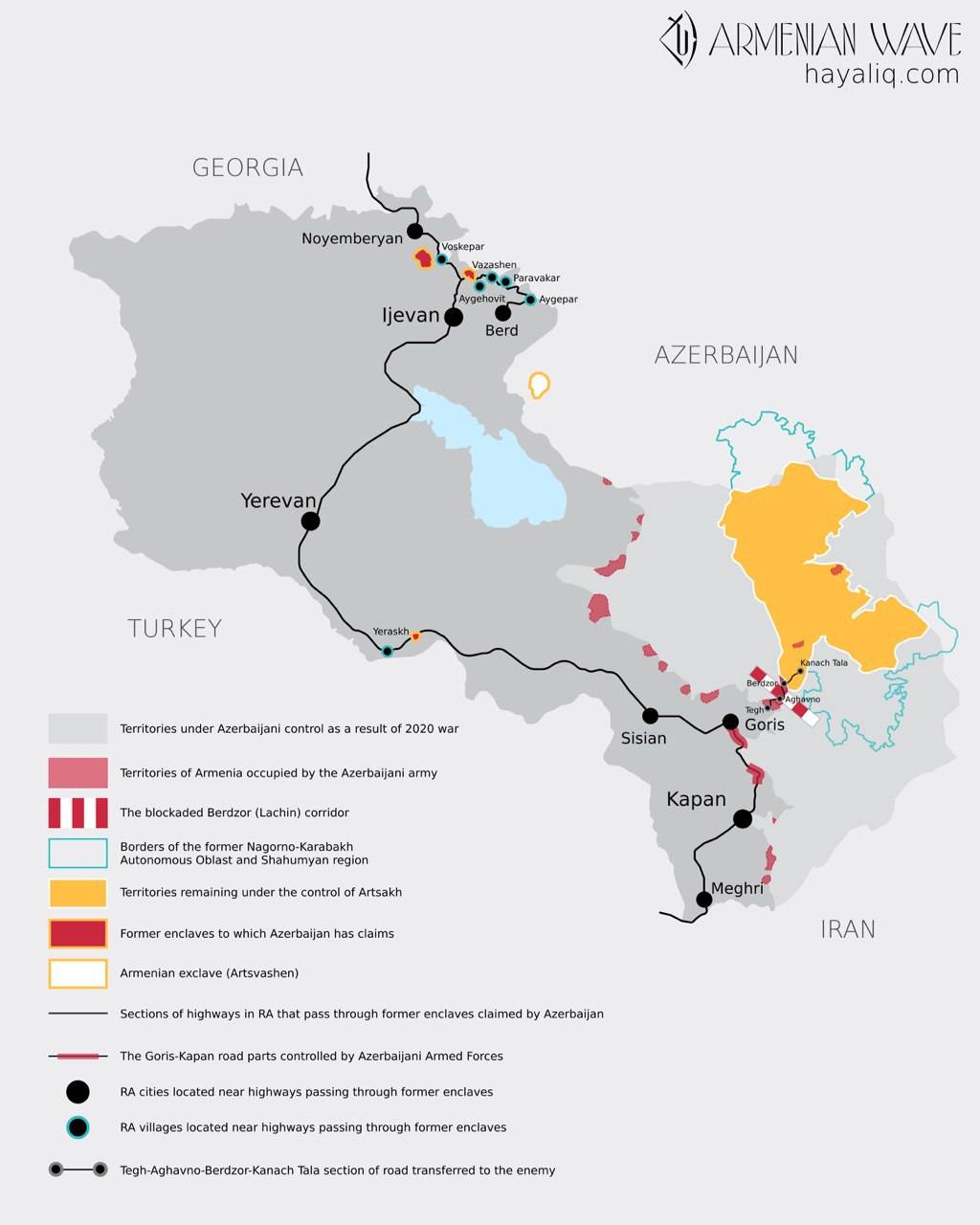

Another artificial way of keeping the situation in tension is the issue of enclaves – small pieces of foreign territory which during the existence of the USSR were located in the Armenian and Azerbaijani SSRs. Azerbaijan wants its enclaves back under its control, despite the fact that Armenia also has enclaves with Azerbaijani territory, not counting the >140 km2 of territory occupied by Baku after 2020. The situation is complicated by the fact that an Armenian strategic highway connecting the country to Georgia passes by one of these enclaves. In reality, the only realistic ‘peaceful’ approach here is to leave the enclave question for a post-peace treaty delimitation and demarcation process, where such territories could be exchanged to benefits either side countries. However, the current tensions over regarding the enclaves represents a possible scenario for a further military incursion by Azerbaijan.

At the moment, there are three Azerbaijani enclaves in Armenia which are located in the Tavush province, located in Armenia’s North, and the Ararat province, located North of the Nakhchivan exclave. All are approximately 3-4 km from the border, which theoretically makes them a possible target for a limited rapid operation. However, the parts of the northern border where enclaves exist are both relatively well fortified and are located in mountainous and forested areas. During the 2020 Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azeri troops were not able to breach the defences in the northern parts of Nagorno-Karabakh, despite a landing a hard blow at the beginning of hostilities. By contrast, Armenia’s southern border is much less fortified, since it never existed until Armenia’s defeat in 2020, before which this border was shared with the Artsakh Republic. Additionally the terrain in this area is more permissive, mainly comprising open plains. In a scenario where Azerbaijan would seek to link its mainland to these aforementioned enclaves by force, it would need to conduct an offensive on three axes of up to 8-9 km deep, and would likely result a heavy multi-day war. Such a conflict is more difficult to diplomatically ‘sell’ as a limited border skirmish, and as such would carry a greater risk of triggering sanctions. Which perhaps serving as a potential dissuasive element, this does not guarantee such a scenario would not come to pass.

Credit: Hayaliq/Armenian Wave

Another and perhaps the most probable conflict scenario for the near future would be a limited operation on the ‘new’ border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, similar to scale and style to one in September 2022. This means, that Azerbaijani troops will have limited time, but not scale or intensity for the attack, with the probable aim being that Azerbaijan’s forces take their objectives before an international response can be organised. If successful, this could notably change the tactical situation on the borders, as well as put more pressure on the Armenian leadership to make more one-sided concessions, most probably related to the Zangezur corridor and/or enclaves issue. The real scenario may include the same idea as in September 2022 – to create a feasible risk of encirclement of a relatively large Armenian city which is close to border. If in 2022 it was Jermuk, next time it could be Goris (9 km from border) or toward Vardenis (15 km from border), located on the shores of Sevan Lake.

The third, and least probable scenario is a full-scale invasion to Armenia and attempt to occupy all or a large chunk of the Vayots Dzor and Sunik provinces of Armenia, the latter of which is in the South of the country and shares a border with Iran. Azerbaijan’s likely goal here would be to connect its mainland to Nakhichevan and to Turkey, while cutting Armenia off from Iran. However, attempting such an offensive would have serious risks of an international reaction, as well as the the possibility of direct military support from Iran, which is not interested in such scenario coming to pass, as it would dramatically decrease its influence in the South Caucasus.

Long-Term Consequences

Along with the aforementioned scenarios, it is important to assess the long-term trends for both countries’ Armed Forces. At present there is a major capability gap between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which was exacerbated after the former’s defeat in 2020.

Following its victory, Azerbaijan has sustained a relatively high defence budget, which is planned to reach USD 3.8 Bn in 2024. Baku is still undertaking on defence procurement and advice for military reforms mostly from Israel and Turkey. The arms deals are now mostly kept in secret, but high numbers of cargo aircraft fights between the three indicates that they are continuing at pace. The most recent news in this sphere is Azerbaijan’s selection of Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) to upgrade Azerbaijan’s Su-25 combat aircraft, and procurement of a 0.5 metre-resolution remote-sensing satellite and possible procurement of Barak MX air defence system from Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). It can be surmised that Azerbaijan continues to fill its stocks with Israeli and Turkish UAVs and loitering munitions, and is continuing to develop its long-range precision-guided strike capability.

In Armenia, there is more of a shift going on, as the 2020 war saw the devastating of its Armed Forces, especially in Air Defence and Artillery domains. The country boosted its military spending twice, and is due to have a defence budget of USD 1.4-1.5 Bn in 2024. Yerevan tried to rely on Russia, its traditional partner, after the Second Karabakh War, signing a contract worth USD 400 M in August 2021, mostly for air defence systems. The contract has still not been fulfilled, which Russia has justified by citing its own needs in Ukraine. This, along with Russia’s aforementioned refusals to fulfil the alliance treaty, has pushed Yerevan to find new partners.

Credit: Press Office of the Government of Armenia

The most significant one at present is India, which according to local media has secured an armament contracts package worth around USD 1 Bn. This includes such major Indian systems as Akash SAMs (with a memorandum of understanding to procure Akash-NG when it is ready), ATAGS 155 mm L52 towed howitzers, MArG 155 155 mm L39 self-propelled howitzers, C-UAV electronic warfare (EW) systems, licensed-produced Konkurs-M anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs), and other equipment. Interestingly, Armenia made the decision to switch to NATO calibres, and with the number of pieces of artillery being procured, which by some estimations may exceed 150-160, this is a strategic change. Another new partner is France, which is now open to sell NATO-standard weapons to Armenia. First contracts signed on October 2023 include three Thales Ground Master 200 radars, as well as binoculars and sensors produced by Safran. Additionally, memorandum of understanding was signed with MBDA to start the process of procuring Mistral very short-range surface-to-air missiles.

Credit: Press Office of the Government of Armenia

In terms of overall security prospects, the short-term in particular, but also the mid-term currently very much favours Azerbaijan, which lost less equipment in the 2020 war, and has continued to invest a higher amount than Armenia in defence. On the Armenian side, the prospects could look better over the long term, provided the country manages to retain its sovereignty until then. This is because the country is currently undergoing a boom in economic growth, driven in particular by Armenia’s IT sector, with the country’s GDP growing by 12.6% in 2022, likely reaching 10% in 2023, and looking set to remain high over the coming years. By contrast, Azerbaijan’s economy is stagnating and is heavily dependent on fossil fuel exports. The worldwide trend towards decarbonising economies may begin to strongly affect Azerbaijan’s economy after 2030, which may allow Yerevan to secure some breathing room. However, 2030 remains further away than is comfortable, and as such Armenia would do well to secure itself in the present.

Leonid Nersisyan

![BVRAAMs: Closing the horizon This photo showing a piece of the wreckage of an Indian Rafale, serial number ‘BS 001’, showed up on social media shortly after the IAF’s night operations of 6/7 May 2025. [Vigorous Falcon X Account]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Rafale-Wreckage-Piece_Vigorous-Falcon-X-Account-Kopie-218x150.jpg)