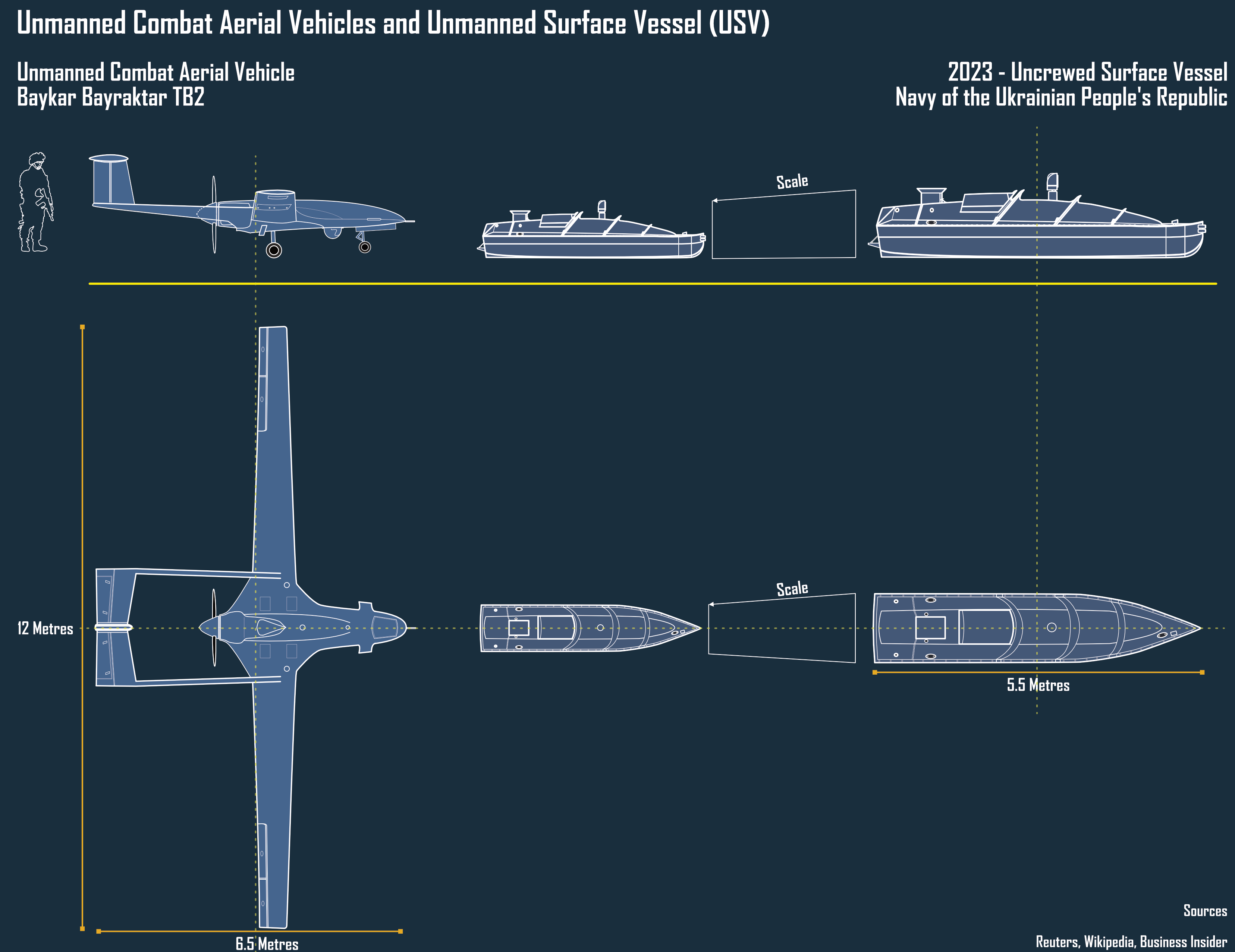

Since at least late-2022, Ukraine’s ingenuity and necessity led it to experiment with maritime uncrewed systems (MUSs) or what in ordinary language are referred to as ‘sea drones’. These have had a profound impact on its efforts to combat Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

In October 2022, Ukrainian video footage surfaced, obtained through GoPro-style camera mounted on several uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) getting closer to an Admiral Grigorovich class frigate, possibly the then-flagship (following the sinking of the Mosvka) of the Black Sea Fleet Admiral Makarov.[1] According to the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD), the attack involved eight USVs and allegedly four where destroyed and other three exploded on land, suggesting that those USVs where not employed for intelligence and reconnaissance but for targeting ships.[2]

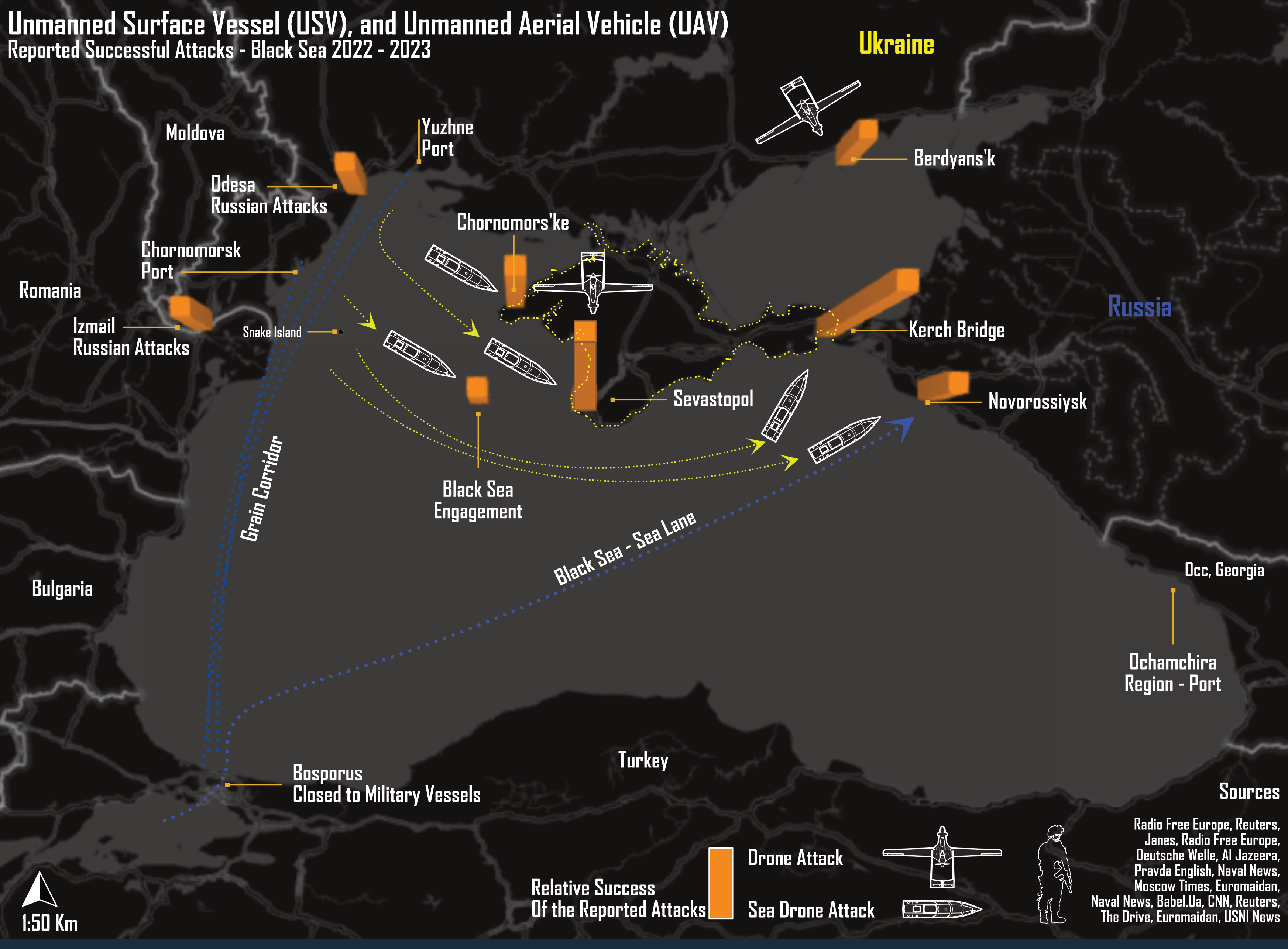

Military analysts have more or less enthusiastically endorsed the Ukrainian capacity to use the MUSs to repel the Black Sea Fleet out of range of key areas, allowing the defence of Odessa and Snake Island from the sea.[3] There are indications that MUS use had had some wider-reaching effects; for instance, through 2023 and 2024 Russia been increasing the capacity of a naval base in the occupied Georgian region of Abkhazia.[4] This may be due to it representing a more secure port to dock its vessels, due to the threat of MUSs.

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

Thus far, relatively few analysts have paid attention to the marked difference between the effects of drone warfare on land and at sea. Gen Valery Zaluzhnyi previously admitted that no “beautiful breakthrough” was possible in the summer 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive.[5] One of the commonly-cited reasons for Ukraine’s waning military success from mid-2023 has been the overall effect of drones within the land warfare sphere.[6] Already by October 2023 RUSI Senior Research Fellow, Jack Watling, argued that Ukraine would need to prepare for a “hard winter”.[7] More recently, in April 2024, Kyrylo Budanov, the Chief of Ukraine’s Main Directorate of Intelligence (GUR) stated that Ukraine is “facing a difficult period”.[8] While the full impact of Ukraine’s August 2024 raid into Russia’s Kursk region is still to be decided, to a large extent Ukraine is still facing difficulties along the majority of the front lines.

Drone warfare appears here to stay, as Zaluzhnyi, now Ambassador to the UK, recognised, explicitly advocating Ukrainian expansion in basically all technologies required to make the drones work. Examples include replacing satellite-based global positioning system (GPS) positional information with solutions using ground-based antennas, improving resilience to electronic warfare (EW), along with efforts to contest Russian air dominance, among others.[9] The new commander in chief, Col Gen Oleksandr Syrskyi, in spite of having been criticised for being ‘the product of the Soviet military doctrine’, seems to not have significantly changed this approach toward drones and their use on the battlefield.[10]

Although Russian attacks seem to be effective, they have still yet to pull off any ‘spectacular breakthroughs’, and their offensive efforts exact a high toll in lives and equipment. Ukrainian lines in some areas are being pushed back, but are still holding in other areas, even amidst Ukraine’s difficulties with recruitment.[11] By contrast, Ukraine has seen what are arguably more strategically-significant successes in the Black Sea.[12]

The strategic importance of the Black Sea: Still never fully appreciated

The strategic importance of the Black Sea lies primarily in its logistical value for Russia. Russian military logistics relies heavily on railroads and specialised brigades, such as the Material Technical Support (MTS) brigades, which play a pivotal role in supplying the armed forces.[13] These brigades are vital for strategic and operational logistics, but they have faced challenges, especially during the early days of the full-scale War in Ukraine. One significant limitation is their capacity, as they can move only a fraction of what a large, capable cargo ship such as the SPARTA IV can carry.[14] Moreover, in recent times, Ukrainian sabotage efforts have hindered the normal logistical flux through railways, although Russia was still able to move munitions from North Korea and the far east to the Ukrainian theatre.[15] However, the situation is still far from ideal.

The Black Sea’s importance to Russia’s logistics network becomes evident when considering the difficulty of moving such large quantities of supplies by rail alone. Therefore, maintaining control and access to the Black Sea is strategically vital for Russia’s military operations and Russia has a strategic advantage over Ukraine at sea.[16]

Moreover, Russia has a significant military presence in the Black Sea, as it has an entire fleet and associated infrastructure in two major ports (Sevastopol, and Novorossiysk), minor ports (such as Fedosia), along with a likely refurbished naval base in Abkhazia, and it can use Crimea as effectively an ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ and logistics platform. Ukrainian attacks targeted the Kerch Bridge with USVs,[17] Storm Shadow missiles were used in Crimea,[18] which reportedly critically damaged the Rostov-on-Don Project 636.3 Improved Kilo class submarine on 13 September 2023.[19] The same submarine was struck again on 2 August 2024, and claimed to have been sunk, though the weapon used was not mentioned.[20] Russia tried to improve its defensive measures securing entry to the port of Sevastopol, but appear to have decided to relocate part of the fleet, especially after the repeated successful attacks mainly from the air.[21]

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

In fact, the main successes of the Ukrainian efforts against the Russian overwhelming presence at sea were caused by missiles as much as from USVs. Ukraine sunk the flagship of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet Moskva in March 2022, thought to have been through a R-360 Neptune anti-ship cruise missile manufactured in Ukraine (and so representing a major success for Ukraine’s military industry).[22] Recently, this happened again with the Kommuna submarine rescue ship, purportedly struck by another Neptune missile.[23]

True, the Moskva possibly sunk thank to the Russian incompetence to manage the fire which broke out, but still, it was a major success. Secondly, the reported destruction of the Kilo class submarine, Rostov-on-Don, which will not recover for some time, was due to a UK Shadow Storm missile, not an MUS.[24] After all, it was at the dry dock in Sevastopol, a difficult target from the sea but an ideal target from the sky. Third, they sunk the Saratov, an Alligator class landing ship tank (LST), but it was very early on the war, hence unlikely to have been hit by USVs, which started to be operated later.[25] The Kerch Bridge was attacked by both missiles and USVs, some possibly carrying 850 kilograms of explosives.[26] However, the operation which has the success in damaging the bridge was a truck bomb attack, but this is still possibly contested.[27] As it stands, MUSs did not prove able to bring the bridge down and, at best, destroyed two spans of the bridge.[28]

MUSs can face various challenges to successful employment; for instance, they can reportedly be repelled with machine guns once they are spotted.[29] Moreover, they require significant work from the intelligence operatives, as the targeting process for multiple MUSs requires an impressive amount of work. This is true on land, and it is much more truer at sea, where there are often no visible points of reference, and the target has to be known far in advance to establish a successful operation to strike it effectively. This is quite clear from the footage released by Ukrainian units. In fact, MUSs are possibly mainly employed in special operations by Ukraine’s GUR, who have proven to be among the most efficient and deadly groups in the war, able to have significant cross-domain impact.

According to a recent video, at operational level, the MUS kill-chain should approximately comprise the following steps.[30] Firstly, there is intelligence gathering on where the target (vessel) is located and when is going to move. Once this is ascertained, Ukraine launches roughly three to five attack USVs and at least one reconnaissance drone serving as a C4I-enabler, hoping to catch the ship hours from where it was last reported. When the ship is spotted, multiple attack drones are sent after the ship, possibly hoping to exploit an ‘indirect approach-operational tactic’.[31] Then, they try to strike the target at the centre (as with the Moskva), where the munitions and/or fuel is usually stored and the possibility to strike the target is higher. Thus far, these USV attacks have proven that they can sink a high tonnage vessel, but typically not with just a single USV; a concerted operation with multiple attacks on a vulnerable target is needed.

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

Remarkable tactical successes and some strategic gains

It took time for USVs to prove they can sink a vessel, which probably means that Ukrainian targeting units, possibly GUR, needed time to experiment with and test the appropriate intelligence cycle, operational and tactical planning, and proper execution. USVs were able to severely damage the Olenegorsky Gornyak, a Ropucha class landing ship, on 4 August 2023.[32] The ship was visibly damaged, but it did not sink. The USV operator(s) possibly tried to hit the fuel and engine rooms, or it simply tried to hit the centre of the ship for maximising the chances for a successful impact on target.

In another case, a USV targeted a Russian tanker, the Sig, in August 2023. Its estimated 450 kg (992 lb) of TNT equivalent payload was able to damage, but not sink, the ship.[33] In other instances, USVs were able to reach the port of Sevastopol multiple times, although the Russian MoD declared that it destroyed 17 USVs.[34] While the Russian MoD figure should be treated with a degree of caution, it does seem the case that numbers matter in USV strike operations, and it is so far unclear how many are needed for effective strikes.

A notable incident in USV use occurred on 26 December 2023, when the Ropucha class landing ship Novocherkassk was struck in the Crimean port of Fedosia, and was reported to have been sunk.[35] This marks the first occasion where USVs proved that they were able to sink vessels, and was closely followed by Ukraine’s USVs sinking the Tarantul class corvette Ivanovets on the night of 31 January/1 February 2024. A pack of USVs were able to strike a hard target again on 14 February 2024, the Ropucha class landing ship, Tsezar Kunikov, and sinking it.[36] Admiral Viktor Sokolov was removed as commander of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet on 15 February 2024, likely as a direct outcome of these attacks.

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

These are all remarkable tactical successes, which were able to reopen the grain corridor for the time being, allowing Ukraine to significantly increase its grain exports from the relative lows seen in the summer of 2023.[37] The route is the most direct, and the time required to move the goods is still not back to normal, but the simple fact that Ukraine is able to move civilian cargo by sea at all is vital for the Ukrainian economy. Finally, the greater success is in what the USV facilitated: the significant removal of Russian ships from Sevastopol, with these being redeployed in Novorossiysk and possibly to the refurbished port in Abkhazia.[38]

However, these victories, as remarkable as they are, are not due the USVs exclusively, but rather on a combinations of weapons that together act as an ‘orchestra’ in which USVs form a key part. USVs are therefore no doubt useful, but a comparison with the UAVs will show how different their effects are at the strategic level.

UAVs: more interesting than tactical nuclear weapons?

In the land warfare domain, UAVs allow their user to achieve multiple results. Firstly, as it was argued for in the case of tactical nuclear weapons, they restrict the opponent’s capacity to concentrate forces on a sufficient scale to create the conditions for the acclaimed manoeuvre warfare.[39] This is achieved for several different reasons. For starters, UAVs allow their user to conduct reconnaissance and gain situational awareness from afar, thereby also serving as enablers for systems such as artillery. Secondly, UAVs and loitering munitions can also be used to directly target and destroy armoured vehicles. Both measures together incentivise dispersion and can cause disruption to the movement and coordination of armoured formations, as well as degrading the level of firepower the opponent has available. Thirdly, they create an additional level of psychological burden, especially during movement. Considering the already heavy psychological toll inflicted through traditional artillery barrages, knowing that the drones are flying around searching for you is widely reported as a harrowing experience by both sides. Fourthly, UAVs allow their user to conduct guerrilla-style warfare, with lower levels of direct engagement, using equipment supplied mostly by Ukrainian civilian developers and engineers, who have proven capable of creating a variety of reconnaissance UAVs, as well as loitering munitions and first-person view (FPV) drones.[40]

This means that the UAV-related technology is overall able to produce multiple types of drones capable of totally different operations but whose combination is able to inflict such a severe toll on the enemy that that they cannot properly coordinate, group, and attack with full effectiveness. As a result, there is enough friction inflicted to heavier armour to heavily disincentivise the accumulation of forces. However, footage also shows that these drones are sufficiently cheap to allow direct targeting of individual soldiers, with some disturbing results.

In essence, drones are defeating conventional armoured vehicles for multiple reasons. Firstly, they are cheap enough that multiple can be expended on the destruction of higher-value targets such as tanks or howitzers, with even the loss of many still being economically worthwhile against such targets. Also, by their nature, they can be replenished reasonably quickly, and (at least for the Ukrainian side) there is a low political price associated with their delivery and use, compared to the bureaucratic and diplomatic work required for Ukraine to receive and use some of the equipment provided by its allies. As such, Ukraine continues to develop a highly-capable drone industry to sustain its war effort.[41]

Finally, flying drones face relatively few restrictions in their movement. Comparatively, there has been limited use of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), though experimentation in their development and employment continues.[42] It is possible that more Ukrainian UGVs will end up seeing use in demining operations or used for casualty evacuation and delivery of supplied, as has been done by the Russians. However, it is difficult to believe they will soon reach the level of UAVs’ capability for the simple reason that there is a lower demand for them. In this regard, land drones are more comparable to MUSs.

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

MUSs – Perhaps not a revolution in military affairs

It is a natural tendency to try to find revolution where there is only evolution. By themselves, MUSs can limit access to given portions of the Black Sea and impose a certain level of friction on the Russian presence in the region. However, as noted by Richard Dunley in his recent analysis on the history and applications of MUSs, they are hardly revolutionary.[43]

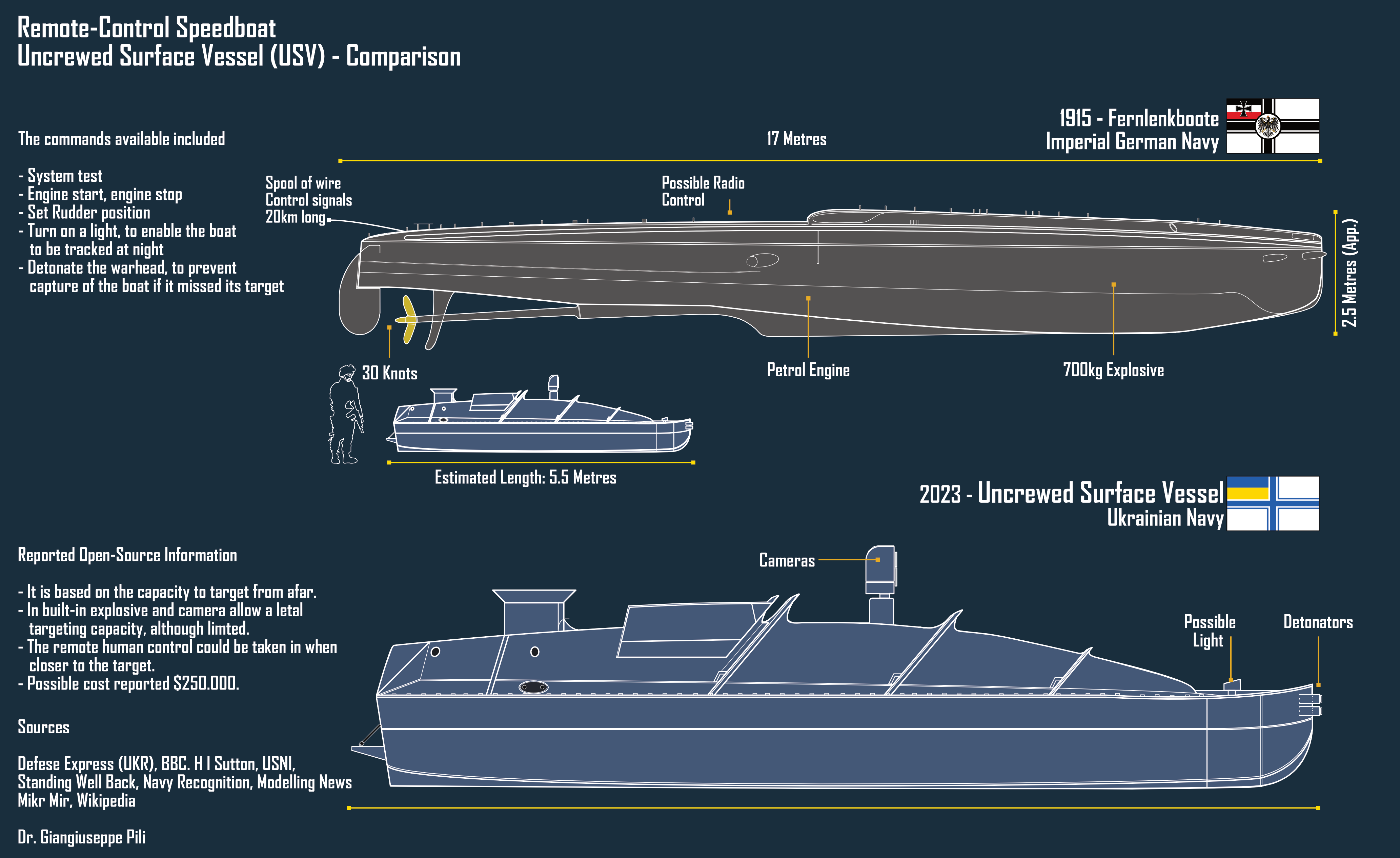

Experimentation with MUSs dates back to at least the First World War; indeed they are even older but only in WWI was the concept proven, albeit revealing difficulties with their practical employment.[44] The Imperial German Navy pioneered early development of USVs, notably in the creation of the Fernlenkboote, a ‘remote-control speedboat’, whose use was exactly the same of the current USVs. These were guided with the help of an accompanying aircraft, whose job was to transmit course correction information to a control post, which could then send those corrections to the USV through a cable. The Fernlenkboote had a spool with 20 km of cable, which was understood to have been later replaced by a radio command system.[45] All in all, the Imperial German Navy managed to strike one Royal Navy destroyer, the HMS Erebus, albeit without sinking it. It is not by chance that it was Imperial Germany which developed this technology, which was used again in WWII; the German Navy was the weakest of the main powers, and USVs appear more suited for use by the underdog. By a similar token, the Japanese Navy also employed MUSs during WWII, and experimented with swarm attacks.[46] It is perhaps it is not by chance that the stronger navies did not have a significant development of MUS tactics, as their existing capabilities were adequate for the task. More recently, Russia is also known to have been experimenting with MUSs, not least because it would be much safer for them to threaten the Ukrainian cargo ships without direct exposure of their more expensive vessels.[47]

It could be argued that MUSs are still relatively new and thus far too untested to be reliable and produced in large quantities. However, a Ukrainian MUS’s cost was reportedly esteemed around USD 250,000.[48] This is much more than most small UAVs used on Ukraine’s battlefields, and around a quarter of the estimated cost of a Neptune missile, as was used in the sinking of the Moskva. Thus, the production cost is both higher than UAVs, and MUSs are mainly effective when used in packs or swarms, as employed by the Ukrainians. This economic reality somewhat hampers their development by a civilian sector at war, as MUSs are too expensive for individuals or cottage industries to develop.

Additionally, although they have come a long way from the limitations faced in WWI, MUS targeting processes remain more difficult than those of UAVs, which can rely on landmarks or terrain. By contrast, MUSs do not have anything comparable, due to the lack of landmarks at sea. This can be partially overcome by using technologies such as satellite navigation, but not entirely.

Credit: Giangiuseppe Pili

Targeting as such looks set to remain more challenging, as the Black Sea is a large space, and information regarding the positions of hostile military vessels is not as available as the locations of enemy positions of land. Finding a ship using satellites alone can be challenging work, and multiple data sources are often required.[49] For instance, if the target is a civilian ship with military value, such as a tanker, it could have an Automatic Identification System (AIS) active, and if so, can be readily tracked. However, important logistics ships often switch off their AIS transceiver when in the Black Sea and follow various routes, aiming for zones where MUSs cannot go or cannot easily get to. It is very unlikely that the SPARTA IV and related ships have been stopped due to MUSs alone, as some have claimed, since MUSs cannot be stationed for long in a given area of interest, they cannot conduct strikes close to Turkey, and the intelligence and targeting cycle behind their use would likely be less effective over long distances. MUSs can be very effective under very specific conditions, but can be expected to be much less if these are not met.

Tactical successes, access denial, and strategic limitations

All in all, the friction imposed by the MUSs has a tactical value that translate into military gains from time to time. They can contest the territory in the best case, but they cannot be used to exert any meaningful strategic control of the sea, in the sense that they cannot directly or indirectly exert power over anything not immediately within their sailing range. This is exactly the opposite of what an aircraft carrier can do. As the US historian Theodore Ferenbach stated: “You may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, and wipe it clean of life – but if you desire to defend it, protect it, and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman Legions did – by putting your soldiers in the mud.”[50] By extension to the maritime domain, this would require permanently stationing vessels capable of exerting power outside of their sailing range. This is why, despite all the hype around MUSs, the United States and China continue to build new aircraft carriers.

MUSs have secured their place in the range of options for denying access to given sea zones, but they are usually not able to project power at a distance, or to strike very far out, in the middle of seas or oceans, nor to serve as a replacement for the variety of weapon systems needed to overload the defensive capacity of the enemy. They can be deadly only under specific circumstances, and with a first-class intelligence cycle, along with remote sensing technologies, used in conjunction with human ingenuity. Russia’s armed forces have been proving more adaptable than seen in early-stage reporting, and this adaptability could extend to finding countermeasures for MUSs. MUSs alone are not able to win a war, but they are able to buy time, and time is an invaluable strategic commodity.

Ukrainian MUSs have indirectly proven how tactical advantages do not necessarily translate into strategic advantages, or grand strategic rebalances. The proof is very simple: if Russia were to hypothetically remove the entire Black Sea Fleet from theatre, Ukraine would still not be able to control the Black Sea, nor meaningfully threaten Crimea from the sea. However, the upsides of this scenario are that Ukraine would not have to worry about missile attacks from the sea, nor the direct contention of its coast, and would have control of its vital grain corridor for exports. While these are undoubtedly beneficial, Ukraine would nonetheless likely prefer to have a conventional navy capable of exerting meaningful control, rather than relying on swarms of MUSs for area denial.

In sum, as all guerrilla fighters know, you fight with what you have, and if you wait long enough you could win. Time remains the key factor and as guerrilla tactics are aimed at buying time, Ukraine’s MUSs may be capable of doing the job, though their overall impact will depend on whether or not the time they buy can be leveraged for meaningful changes to the overall strategic picture.

Giangiuseppe Pili

Author Box: Dr Giangiuseppe Pili is an Assistant Professor at the Intelligence Analysis Program, James Madison University. He is a Senior Associate Fellow with NATO Defence College and an Associate Fellow with the Proliferation and Nuclear Policy research group at RUSI.

[1] Ozberk, T., ‘Analysis: Ukraine Strikes With Kamikaze USVs – Russian Bases Are Not Safe Anymore’, Naval News, 10-2022, available at: https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/10/analysis-ukraine-strikes-with-kamikaze-usvs-russian-bases-are-not-safe-anymore/

[2] Ibid.

[3] RFE, ‘Ukraine Says It Has Retaken Infamous Snake Island; Russia Says It Withdrew For ‘Goodwill”, Radio Free Europe, 06-2022, available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-snake-island-retaken-russia/31922826.html

[4] Seskuria, N., ‘Is Russia Expanding its Battlefront to Georgia?’, Royal United Services Institute, 10-2023, available at: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russia-expanding-its-battlefront-georgia

[5] Méheut, C., and A., E., Kramer, ‘Ukraine’s Top Commander Says War Has Hit a ‘Stalemate’’, The New York Times, 11-2023, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/02/world/europe/ukraine-zaluzhny-war.html

[6] Schmidt, E., ‘Ukraine Shows How Drones Are Changing Warfare’, Time, 08-2023, available at: https://time.com/collection/time100-voices/6317661/eric-schmidt-drones-warfare-voices/

[7] Watling, J., ‘Ukraine Must Prepare for a Hard Winter’, Royal United Services Institute, 10-2023, available at: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/ukraine-must-prepare-hard-winter

[8] ‘”We are facing a difficult period, but Ukraine will not lose” – Kyrylo Budanov in an interview with the BBC’, BBC, 04-2024, available at: https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/articles/cmm35ry9v70o

[9] ‘Zaluzhny: Ukraine faces a “positional” warfare’, Militarnyi, 11-2023, available at: https://mil.in.ua/en/news/zaluzhny-ukraine-faces-a-positional-warfare/

[10] ‘Who is new top commander Oleksandr Syrskyi?’, Deutsche Welle, 02-2024, available at: https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-war-who-is-new-top-commander-oleksandr-syrskyi/a-68216345#:~:text=Before%20his%20most%20recent%20promotion,less%20on%20protecting%20soldiers’%20lives.

[11] ‘Shortage of Ukrainian Armed Forces personnel in Chasovoy Yar’, The Insider, 04-2024, available at: https://theins.ru/news/271095

[12] Pili, G., Crawford, J., Loxton, N., and R., Kolodii, (2024), Smooth Sailing? The Strategic Relevance of (Un)contested Control of the Black Sea, European Security & Defence (Bonn (GER)).

[13] Skoglund, P., Listou, T., Ekström, T., “Russian Logistics in the Ukrainian War: Can Operational Failures be Attributed to logistics?”, Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies, 2022, https://sjms.nu/articles/10.31374/sjms.158.

[14] Pili, G., Crawford, J., Loxton, N., “Ghost ship – Russia’s secret naval fleet”, NATO Defence College, Outlook 01-2023.

[15] ‘Russian Railways Face Mounting Disruptions as Ukrainian Resistance Steps Up Campaign’, Defense Express, 11-2023, available at: https://en.defence-ua.com/news/russian_railways_face_mounting_disruptions_as_ukrainian_resistance_steps_up_campaign-8721.html

[16] Pili, G., Crawford, J., Loxton, N., “Ghost ship – Russia’s secret naval fleet”, NATO Defence College, Outlook 01-2023.

[17] Voichuk, I., ‘SBU unveils new details of marine drone attack on Crimean Bridge’, Euromaidan, 11-2023, available at: https://euromaidanpress.com/2023/11/25/sbu-unveils-new-details-of-marine-drones-attack-on-crimean-bridge/

[18] Axe, D., ‘To Blow Up Warships And Headquarters In Crimea, Ukraine First Had To Roll Back Russia’s Air-Defenses’, Forbes, 09-2023, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2023/09/22/to-blow-up-warships-and-headquarters-in-crimea-ukraine-first-had-to-roll-back-russias-air-defenses/?sh=5b511b6f60e9

[19] H I Sutton, ‘Black Sea Attacks: First Russian Submarine Lost In War Since World War Two’, H I Sutton, 09-2023, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFfURH-qhEY

[20] https://euro-sd.com/2024/08/major-news/39725/ukraine-claims-sinking-of-kilo/

[21] Satellite imagery consulted: Airbus Defence and Space, and European Space Agency Sentinel 2. Dickinson, P., ‘Putin’s fleet retreats: Ukraine is winning the Battle of the Black Sea’, Atlantic Council, 10-2022, available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putins-fleet-retreats-ukraine-is-winning-the-battle-of-the-black-sea/

[22] Gutman, J., ‘The Neptune anti-ship missile: The weapon that may have sunk the Russian flagship Moskva’, MilitaryTimes, 05-2022, available at: https://www.militarytimes.com/off-duty/gearscout/2022/05/12/the-neptune-anti-ship-missile-the-weapon-that-may-have-sunk-the-russian-flagship-moskva/

[23] ‘Ukraine Strikes Russia’s Kommuna Submarine Rescue Ship With Neptune Missiles’, Naval News, 04-2024, available at: https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/04/ukraine-strikes-russias-kommuna-submarine-rescue-ship-with-neptune-missiles/

[24] Brown, S., ‘ANALYSIS: Destruction of Russia’s Kilo Class Submarine Unique in More Ways Than One’, Kyiv Times, 09-2023, available at: https://www.kyivpost.com/analysis/21778

[25] Sutton, H.I., ‘Satellite Images Confirm Russian Navy Landing Ship Was Sunk at Berdyansk’, USNI News, 03-2023, available at: https://news.usni.org/2022/03/25/satellite-images-confirm-russian-navy-landing-ship-was-sunk-at-berdyansk

[26] Ozberk, T., ‘New Video Confirms Ukraine’s Latest Bridge Attack Was Done With Kamikaze USV’, Naval News, 08-2023, available at: https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/08/new-video-confirms-ukraines-latest-bridge-attack-was-done-with-kamikaze-usv/

[27] ‘SBU chief Malyuk on how Crimean Bridge was attacked — twice’, Ukrainian Voice, 08-2023, https://english.nv.ua/nation/sbu-chief-malyuk-on-how-crimean-bridge-was-attacked-twice-50348824.html

[28] ‘SBU unveils new details of marine drone attack on Crimean Bridge’, Euromaidan, 11-2023, available at: https://euromaidanpress.com/2023/11/25/sbu-unveils-new-details-of-marine-drones-attack-on-crimean-bridge/

[29] ‘Frontline report: Seven Russian warships targeted by Ukraine in just four days, with three destroyed and at least two damaged’, Euromaidan, 09-2023, available at: https://euromaidanpress.com/2023/09/17/frontline-report-seven-russian-warships-targeted-by-ukraine-in-just-four-days-with-three-destroyed-and-at-least-two-damaged/

[30] ‘How the Magura V5 drones drowned the “Cesar Kunikov” VDK in a video from the State Government: analysis and oddities of the Russians’, Defense Express, 02-2024, available at: https://defence-ua.com/photo/jak_dronami_magura_v5_topili_vdk_tsezar_kunikov_na_video_vid_gur_analiz_ta_divatstva_rosijan-293.html

[31] Potter, R., ‘B. H. Liddell Hart, Strategy (1954)’, Classics of Strategy, Jan-2016, available at: https://classicsofstrategy.com/2016/01/19/liddell-hart-strategy-1954/

[32] ‘Image Of Russian Warship’s Hull Torn Open By Ukrainian Drone Boat Emerges’, The Drive, 08-2023, available at: https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/image-of-russian-warships-hull-torn-open-by-ukrainian-drone-boat-emerges

[33] ‘Ukraine hits Russian oil tanker with sea drone hours after attacking naval base’, CNN, 05-2023, available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/05/europe/ukraine-sea-drone-attacks-intl/index.html

[34] Reuters, ‘Russia says destroys 17 Ukraine-launched drones over Black Sea, Crimea’, Reuters, 11-2023, available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-downs-five-ukraine-launched-drones-over-sevastopol-russia-installed-2023-11-07/

[35] Sutton, H.I, ‘Timeline of 2022 Ukraine Invasion: War In The Black Sea’, Covert Shores, 23-2024, available at: http://www.hisutton.com/Timeline-2022-Ukraine-Invasion-At-Sea.html

[36] ‘How the Magura V5 drones drowned the “Cesar Kunikov” VDK in a video from the State Government: analysis and oddities of the Russians’, Defense Express, 02-2024, available at: https://defence-ua.com/photo/jak_dronami_magura_v5_topili_vdk_tsezar_kunikov_na_video_vid_gur_analiz_ta_divatstva_rosijan-293.html

[37] ‘How much grain is Ukraine exporting and how is it leaving the country?’, BBC, 02-2024, available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-61759692

[38] ‘Putin’s fleet retreats: Ukraine is winning the Battle of the Black Sea’, Atlantic Council, 10-2022, available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putins-fleet-retreats-ukraine-is-winning-the-battle-of-the-black-sea/

[39] For an in depth study, Dr. Jack Watling’s work is unreplaceable, Watling, J., ‘The Arms of the Future – Technology and Close Combat in the Twenty-First Century’, London: Bloomsbury, 2024, https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/arms-of-the-future-9781350352988/ and other studies are available at rusi.org.

[40] For this concept I rerefer to the outstanding work of three young analysts, see Rooker, S., Stevens, R., Kurien, J., ‘The Intelligence Community: Back to the Future – Part 3’, The Institute of World Politics, 03-2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4S3ljImPXNc and Rooker, S., Stevens, R., Kurien, ‘Unmanned & Unleashed: Ukraine’s USVs’, Forthcoming.

[41] Sinclair, J., “Ukraine tech sector goes to war | FT Film”, Financial Times, 07-2023, https://www.ft.com/video/742ac4f8-44d7-4ab8-a4e9-5814aae9b566

[42] “Ukraine showed off experimental new land drones, including one mounted with a turret”, Business Insider, 08-2023, https://businessinsider.mx/photos-ukraine-tests-experimental-land-drones-one-mounted-with-turret-2023-8/?r=US&IR=T

[43] Dunley, R., ‘Ukraine-style naval attack drones present challenges, but they are not revolutionary’, The Strategist, 03-2024, available at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/ukraine-style-naval-attack-drones-present-challenges-but-they-are-not-revolutionary/

[44] In fact, it is a Ukraine media specialised in military analysis to report the historical inheritance of the new form of sea drones: Defence Express, Перший в світі морський дрон зробили німці в 1915 році, але вийшло невдало, Defence Express, 08-2023, https://defence-ua.com/weapon_and_tech/pershij_v_sviti_morskij_dron_zrobili_nimtsi_v_1915_rotsi_ale_vijshlo_nevdalo-12459.html

[45] Standingwellback. ‘German Explosive Remote-Control Speedboats of WW1 and WW2’. Standing Well Back, 5 Feb. 2020, https://www.standingwellback.com/german-explosive-remote-control-speedboats-of-ww1-and-ww2/

[46] Ibid.

[47] Meduza, “Ukraine Commander-in-Chief confirms Russia’s use of naval drones”, Meduza, 02-2023, https://meduza.io/en/news/2023/02/11/ukraine-commander-in-chief-confirms-russia-s-use-of-naval-drones

[48] ‘Sea drones: What are they and how much do they cost?’, BBC, 09-2023, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-66373052

[49] As the author knows very well in his capacity of OSINT geospatial analyst.

[50] See T. R. Fehrenbach (1994). “This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History”, Simon & Schuster Books For Young Readers

![The continuing evolution of tube artillery The 8×8 variant of the CAESAR SPH on display at the Eurosatory 2024 exhibition. [Tank Encyclopedia, courtesy photo]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/caesar-8x8-at-eurosatory-2024-Kopie-218x150.jpg)

![Beyond the drone line: Lessons from the drone war in Ukraine A typical RF controlled FPV drone, shown during take-off. These little platforms have already reshaped the battlefield significantly, but in many ways have not yet reached their full potential. [Armyinform]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/RF-FPV-Drone-Takeoff_Armyinform-Kopie2-218x150.jpg)