More than two and a half years into the Russo-Ukrainian War, both nations have endured significant human losses while making minimal territorial gains. The conflict has evolved considerably, though neither Russia nor Ukraine are fighting as they did at the war’s outset in 2022. A noticeable shift toward innovative warfare and technology is evident. Ukraine has taken the lead in implementing and practically applying these innovations, while Russia is also striving to adapt, particularly in organisational and technological areas.

This is the first large-scale military conflict in recent decades involving two relatively well-equipped regular armies of relatively comparable technological capabilities. The only conflict of similar magnitude and characteristics in recent history was the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. Military specialists studied this conflict extensively, and experts’ interest in such confrontations and preparations diminished over time as the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War marked the decline in the relevance of confrontations between conventional armies. In subsequent years, military threats took on a different character.

The last war involving the Soviet Union was the War in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, fought by the Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces against irregular Afghan mujahideen guerrilla formations. Later, the Russian Army engaged in two ‘internal wars’ in the North Caucasus, also against semi-guerrilla rebel groups. These experiences and those of various peacekeeping missions shaped a new vision of future military conflicts. In the Russian school of military thinking and beyond, the prevailing view became that future wars would involve professional army units equipped with high-tech weaponry, communications, and intelligence systems, combating lightly armed militias, religious extremists, and transnational criminal organisations.

Credit: Yana Amelina, via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA 3.0

The first conflict involving the Russian Armed Forces against a regular army, albeit minor, was the brief war with Georgia in August 2008, often called the ‘five-day war’, This conflict unexpectedly exposed several deficiencies within the Russian Armed Forces; notably, it became clear that their communication systems were outdated. Georgian forces quickly intercepted Russian communications, leaving the Russian troops highly vulnerable to the Georgian Army’s electronic warfare capabilities. In many instances, civilian mobile networks were used to manage troop movements.

Military personnel of the Russian Armed Forces, particularly the 58th Army, were poorly prepared; the main contingent consisted of conscripts without proper training. Technical issues were also apparent; a large amount of equipment broke down on the march, even before combat operations began. Logistics and rear support were disorganised, and there was a noticeable lack of effective command, control, and coordination among the forces. The situational awareness at all levels of headquarters was also weak. Modern unmanned systems were almost entirely absent, and intelligence agencies’ overall performance was inadequate. Open sources indicate that the Russian forces deployed only one unmanned complex, the Pchela. Additionally, Russia’s Zoopark-1 artillery counter-battery radar systems were missing, and forward units lacked forward air controllers.

It was the Russian invasion force’s numerical superiority over the Georgian Army that offset its shortcomings. The total strength of the 58th Army, along with attached airborne units, air defence forces, and other units and subunits, reportedly reached 70,000 personnel, compared to the Georgian Army’s 20,000 troops.

After 2008, the Russian Armed Forces underwent extensive reforms, which, according to official statements at the time, aimed to address the deficiencies revealed during the war in Georgia. The state defence order framework approved the procurement of new weapons, military equipment, and upgraded intelligence and communication systems. Defence Minister Anatoly Serdyukov’s reforms in 2008–2012 focused on creating a high-tech, mobile professional army equipped for rapid local operations.

Credit: Russian MoD

The Sozvezdie Unified Tactical Level Command and Control System (ESU TZ; also called ‘the Sozvezdie system’) was developed to improve situational awareness at tactical-level headquarters, optimise decision-making cycles, and enhance unit coordination. Russian media and official sources frequently claimed that the Russian Army was becoming more assertive and qualitatively improving year on year.

These reforms positioned Russia for 2014, when, following the Ukrainian Maidan Revolution, it occupied the Crimean Peninsula and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Moscow successfully operated with Special Operations Forces units and several private military companies (PMCs). Contributing factors to their success included political uncertainty within Ukrainian society, weak control over the armed forces and state institutions by the new Kyiv authorities, the element of surprise, and the pro-Russian orientation of some senior Ukrainian security officials. The near absence of a functional army in Ukraine further facilitated Russian advances into the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, where various Ukrainian volunteer battalions formed the core of resistance against Russian aggression.

The year 2014 also marked a turning point in Ukraine’s approach to national security. In response to the conflict in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, Kyiv declared the start of the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) and began restructuring its nearly derelict army.

Credit: Anton Holoborodko, via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA 3.0

The Russians’ use of irregular warfare tactics, including limited military actions involving local populations and regular troops disguised as ‘local militia’, triggered Ukraine to implement several measures to rebuild its armed forces. Some military units were restructured and reformed, and the National Guard of Ukraine was established, incorporating many volunteer battalions formed in 2014. A law on territorial defence was passed, leading to the formation of the Territorial Defence Forces. With assistance from Western allies, personnel training programmes were initiated, and consultations on military reforms were conducted. The nationwide volunteer movement significantly influenced the new Ukrainian Army’s training and equipment; volunteers organised personnel and reserve training, conducted research and development in various technical fields, and more.

Lessons of the Russo-Ukrainian War

A new phase of the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine began on 24 February 2022 with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The rapid advance of Russian troop groupings in various directions, occupying large expanses of territory with little resistance, at the time led many experts to expect that Ukraine’s military defeat was imminent.

However, many fundamental characteristics of the Russian Army had remained largely unchanged since 2008. Widespread breakdowns of military equipment marked the early days of the Russian offensive in February 2022; abandoned vehicles were documented by reporters and military bloggers across multiple regions from the Russian border to deep into Ukrainian territory, along all routes of advance. Additionally, the troops appeared to be disoriented; commanders of forward units and leading columns lacked GPS or Russian GLONASS satellite navigation systems, and even basic, up-to-date maps of the area were unavailable. The outdated maps provided had not been updated for years and often did not correspond to the actual terrain, with new roads, districts, and other developments missing. Coordination between units and subunits was also poor, and supply columns struggled to keep pace with the advancing troops, frequently confusing routes and falling into ambushes by Ukrainian local militias.

Credit: Russian MoD

The rapid advance of Russian troops was likely not due to a failure in Ukrainian defence or confusion within the Ukrainian command (except perhaps along the Southern axis). Several indicators suggest that the Ukrainians had accurately anticipated the timing of the invasion. Observations supporting this include:

- Most Ukrainian military units had been withdrawn from their permanent locations.

- Aviation assets had been relocated from their airfields to temporary field airstrips, with decoy targets left behind, which the Russian Ministry of Defence later claimed as destroyed Ukrainian Air Force equipment.

- Air defence systems, tanks, armoured vehicles, and artillery had been pre-emptively relocated and partially concealed.

- Many weapons and ammunition depots had been dispersed.

The initial withdrawal of Ukrainian forces from certain areas was likely a strategic decision, recognising that the balance of power would not allow for effective defence in those positions. By retreating deeper into their territory, Ukrainian forces established defensive strongholds in urbanised, densely built-up areas, making it more challenging for the enemy to detect, identify, and engage targets. For the advancing Russian forces – whose numbers were insufficient to conduct operations across such an extensive front – the Ukrainians created significant difficulties by extending the supply routes the Russians needed to maintain their advances. As a result, supply columns, often lacking adequate escorts, were forced to travel dozens of kilometres through hostile territory, leading to frequent ambushes and substantial losses.

Simultaneously, Ukrainian forces successfully inflicted significant damage on the advancing enemy, aided by good intelligence on their movements. In addition to regular reconnaissance units and assets operating behind Russian lines and at the front, civilians from occupied territories provided substantial information. The Ukrainian command also received real-time data from video cameras installed in various parts of towns and along roads.

The Russians likely intended to disrupt Ukrainian defences by using the element of surprise, but they failed. A notable example is the Russian paratrooper (VDV) helicopter landing operation at Antonov airport, in the Kyiv suburb of Hostomel, in February 2022. The Ukrainians responded with remarkable speed, effectively neutralising most of the paratroopers and the reinforcements arriving in a second wave, creating conditions that made it impossible for larger forces to land.

Credit: Kyiv City State Administration/Oleksiy Samsonov

These early days of the war offer the first and most critical lesson: the Russian command erred during the planning stage by underestimating the enemy, overestimating their own strength, and relying on unverified information. According to several sources within the Russian Armed Forces, there was a prevailing belief that the local population would welcome the Russian troops with open arms and that Ukrainian forces would either switch sides or be demoralised and disperse without offering serious resistance. While such an assessment might have been relevant in 2014 or 2015 in some specific areas of eastern Ukraine, by the time the war began, the psychological disposition of the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians had changed dramatically.

The second lesson is that the Russian Army has retained a rigid, hierarchical command structure that has been entrenched for decades. The military adage ‘initiative is punishable’ was particularly evident: although combat regulations require soldiers at all levels to demonstrate courage and initiative, taking such initiative is not encouraged. In this environment, junior commanders who act without approval from higher-ups risk punishment unless their decisions result in unquestionable success.

This rigidity has largely stripped unit commanders of the desire and ability to make independent decisions on the ground. Conversely, some unit or formation commanders who understand the necessity of granting broader authority to more junior subordinates tended to avoid doing so due to their subordinates’ low predisposition to take initiative.

The result is that the decision-making cycle within the Russian forces is often twice, or sometimes three times, longer than that of the Ukrainians. At the outset of the war, a Ukrainian battalion commander had as much freedom of action as a regimental commander in the Russian Army, and sometimes even more.

The Russian Unified Tactical Level Command and Control System (ESU TZ), which intended to facilitate coordination and shorten decision-making cycles, never progressed beyond the stage of field trials. Before the war, Colonel Mikhail Teplinsky, Chief of Staff of the 20th Army of the Western Military District, discussed the trials of the ESU TZ in implementing the network-centric warfare concept. He noted that for the military to transition to an automated control system, they must first clearly understand what was needed.

Teplinsky also noted that the only notable achievement of the Sozvezdie system was establishing reliable communications within the “brigade commander–battalion commander–company commander” chain. He further explained that another automated command and control system, Akatsiya, used at the army headquarters level, was completely incompatible with ESU TZ. According to Teplinsky, data from one system could not be transferred to the lower levels of the Sozvezdie system. He also criticised the graphical editor used in Sozvezdie, calling the system poorly-designed. In reality, little has changed in the Russian Armed Forces’ command and control (C2) since 2008.

Credit: Logika

By contrast, Ukraine has employed the Kropyva system, a software-based solution developed by volunteers in 2015 to modernise existing weapon systems. Kropyva integrates reconnaissance, command, and fire control systems into a unified information network, allowing Ukrainian soldiers to request artillery fire using a standard tablet computer. The system uses shortwave and digital radios compatible with NATO standards and is fully interoperable with other communication channels, including satellite and fibre-optic links. Kropyva integrates all technical assets, from artillery systems to reconnaissance drones.

The Ukrainian Armed Forces have also implemented and widely used the Delta system, a C2 and situational awareness platform that started operating in February 2023. Delta allows the Ukrainian military to track the movement of Russian troops and monitor the battlefield situation in real-time. Verified active-duty personnel can access the programme online using authorisation and two-factor authentication on a special website. Authorised users can view and input data about known enemy positions, observed aircraft, ground vehicles, and more. Delta integrates with various external intelligence systems, such as satellites, radars, multiple sensors and cameras, and the Telegram chatbot e-Vorog. Soldiers can input their data onto a shared map and view information entered by other military personnel or intelligence services. Each user is assigned a level of access corresponding to their combat missions and rank. Delta also includes a secure messenger for communication between soldiers from different units — an asset the Russian Army still lacks. Even basic radios and navigators remain a significant challenge for Russian forces, with volunteers working tirelessly to bridge this gap.

The problems and shortcomings faced by the Russian Armed Forces since the start of the invasion in 2022 are complex and interconnected. Some experts focus on technical and technological issues, comparing the quantitative and qualitative aspects of artillery, aviation, tanks, and personnel on both sides. Others point to the ‘human factor’, for instance, the insufficient number of junior and mid-level commanders and the incompetence of the Russian Armed Forces’ high command as the primary problem.

Credit: RecoMonkey

Both perspectives hold merit, but in most cases the personnel issue is more critical. Ultimately, the Russians’ absence of certain technical capabilities or their lack of modernisation stems directly from the higher command’s flawed assessment of the state of the Armed Forces and their misguided vision of likely combat scenarios.

Technical component: Weapon systems and artillery

Artillery remains the backbone of firepower on the battlefield. Due to various factors, the Russian Armed Forces have been unable to realise the full potential of their air force, including attack aviation, leaving most tasks related to enemy fire suppression to tube and rocket artillery. At the beginning of the conflict, Russia and Ukraine had qualitatively comparable artillery forces, largely consisting of Soviet-era equipment. Both sides maintained parity for some time, but by the summer of 2022, Russia had gained superiority in artillery. For its offensive operations in the Donbas region, Russia deployed more than 1,100 pieces of tube artillery, typically grouped into formations of about 80–90 guns to support brigade groups consisting of three to four battalion-tactical groups. Russia’s artillery advantage in the Donbas during May and June 2022 was estimated to be 12 to 1. However, both sides remained relatively equal in terms of fires effectiveness.

Although Ukraine’s artillery ammunition stocks were limited and the Ukrainian Armed Forces relied, and continue to rely, on assistance from NATO members, they achieved effectiveness through the efficient coordination between reconnaissance assets and firepower and the widespread use of precision munitions. In contrast, with weak reconnaissance support and a shortage of precision munitions, the Russian Armed Forces relied more on the massed use of conventional munitions, primarily conducting massive area bombardments. Additionally, the long distances required to deliver ammunition to the front lines further challenge the Russians, and the concentration of these munitions in intermediate depots increases the risk of their destruction by long-range precision systems, such as the M142 HIMARS multiple rocket launcher (MRL).

The Russians judge that quantitative and qualitative superiority over the enemy is necessary for successful military operations. Yet massed artillery formations, reminiscent of those used during World War II, are no longer effective. The enemy quickly detects artillery divisions, meaning that batteries in firing positions are highly vulnerable. This reality necessitates the dispersion of fire assets, the ability to quickly fix coordinates on the ground, and the rapid change of positions, which raise the qualification requirements of artillerymen, especially gun commanders and spotters. In these cases, there is an acute need for reconnaissance drones that can support artillery platoons and, in some cases, even individual guns.

Credit: RecoMonkey

Russian artillery units still lack effective, portable, compact, and lightweight automated C2 systems that would allow for quick and efficient fire preparation and control calculations in response to the changing tactical situation on the battlefield. There is a noted shortage of automated artillery fire control systems such as Malakhit, personal tablets for artillerymen, laser rangefinders, and target designators. Additionally, there is a critical shortage of counter-battery radar systems. According to Russian specialists, the Russian Ground Forces had only ten Zoopark-1M systems at the start of the conflict. Based on combat experience, it has been decided to accelerate the production and delivery of mobile artillery reconnaissance posts such as the PRP-4A Argus and 1B75 Penicillin and optoelectronic systems such as Ironiya-M. The Russian Ground Forces are also attempting to develop an advanced, multicomponent reconnaissance and targeting system. However, most of the latest models are available in limited quantities and are mainly used by special units. One possible reason for the slow adoption of these systems across the broader military is production challenges, mainly due to a shortage of components caused by sanctions. However, the Russian military-industrial complex is expected to address this problem eventually.

At the same time, Russia has increased the production and supply of precision-guided artillery munitions, such as the Krasnopol-M2 and Gran. While such munitions sometimes lag behind their NATO counterparts’ key characteristics, Russian precision-guided shells are more affordable and available in greater quantities.

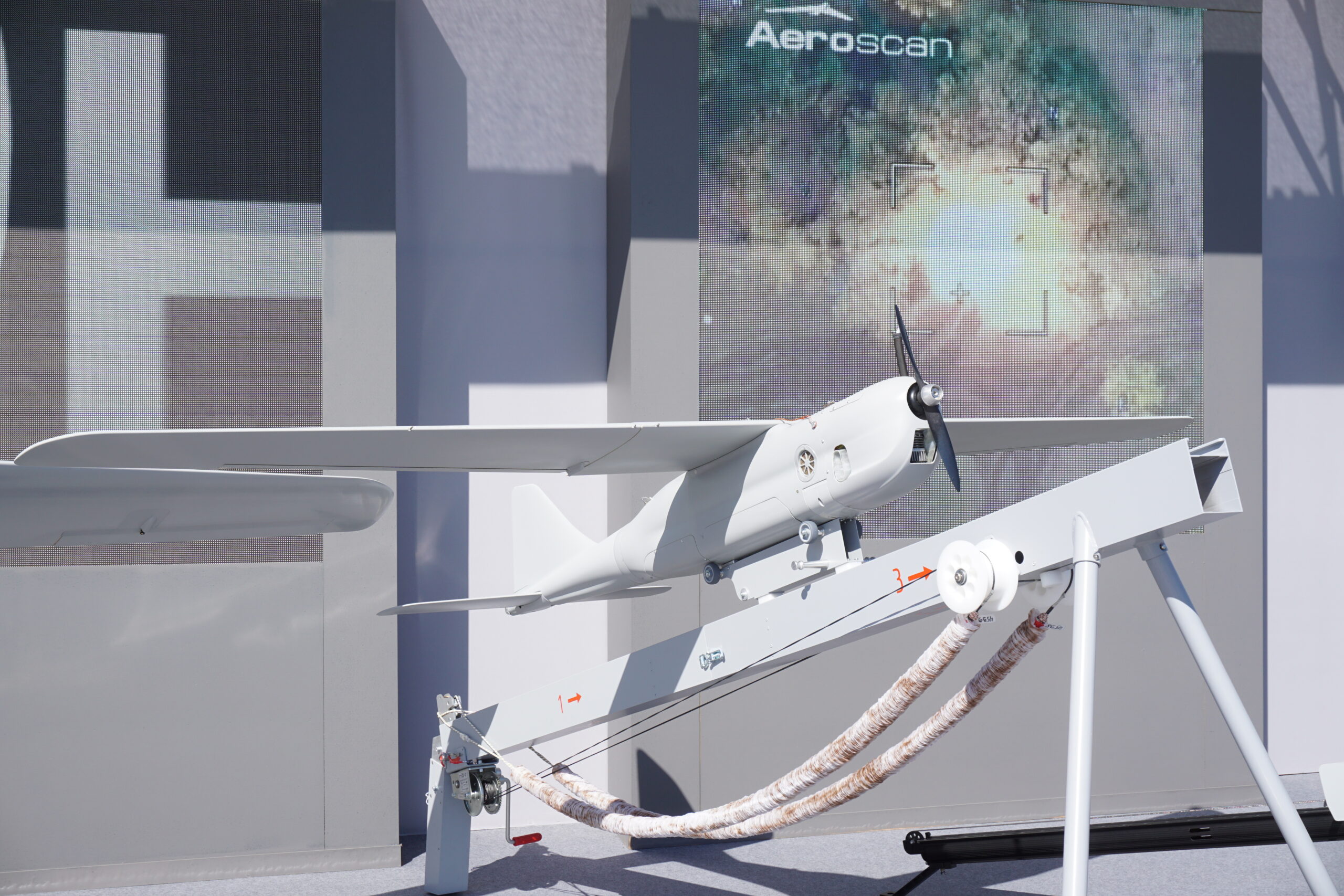

Unmanned aerial vehicles

The Russian Army has made significant progress in the UAV sector. At the beginning of the war, Russian UAVs deployed were primarily reconnaissance drones such as the Orlan-10 and Eleron-7. Regarding UAV range and scale of use, the Russian side was significantly behind the Ukrainian Army. However, the situation has changed considerably over time.

Particular attention should be given to loitering munitions, such as the Lancet family, first used by Russian military forces in Syria. During the conflict in Ukraine, Russia has significantly ramped up the production of this type of munition, and modernised it by equipping it with automatic target-acquisition systems, making it much more resistant to electronic warfare (EW) countermeasures. The operational range has also improved; while the early models had a limited range of up to 40 km, the latest modifications have increased this to around 70 km.

Credit: RecoMonkey

Quadcopters of various models have secured a specific niche in the combat operations of lower tactical units (platoon-company) and are predominantly represented by various Chinese models. The supply of these UAVs to units is primarily carried out by public and volunteer organisations, with the volume of these supplies being enormous. According to some sources, from January to July 2023, drones and their components worth more than USD 100 million were exported from China to Russia. Some analysts estimate that Russia now surpasses Ukraine in the monthly production of various types of UAVs, with an estimated output of more than 100,000 units per month.

Armoured combat vehicles

Experience from the war has highlighted a significant increase in the importance of conventional weaponry, such as tanks, various armoured combat vehicles, and specialised armoured vehicles (engineering, evacuation, medical). This has led to a renewed emphasis on mass production, which will require some standardisation to maintain technological sophistication, specified characteristics, and the maintainability of equipment.

The experience gained also indicates that having a wide range of weapon types, calibres, and chassis for various armaments – and a lack of standardisation – negatively impact the combat readiness and capability of units and formations. Consequently, there is an anticipated trend toward reducing the use of purely specialised vehicles and focusing instead on the maximum possible implementation of widely available commercial platforms, components, and assemblies.

Operational art and tactics

Operational art and its derivative tactics have not undergone significant changes. The changes are not related to the tactics and types of military operations, but to the weaponry used.

Based on the experience of the conflict, there is a recognised need to revise combat regulations, with adjustments to certain provisions and standards. This experience illustrates the necessity of skilfully combining the mass of the army with nimbleness for troop dispersion. These requirements, previously established with an emphasis on the use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), now also apply to precision-guided weapons. Some experts have claimed these systems can be as effective as WMDs without causing an adverse environmental impact.

Credit: RecoMonkey

The dispersal of combat formations has led to a resurgence of units such as ‘assault groups’ and ‘battalion tactical groups’, concepts that have been known since World War II.

Warfare concepts such as Blitzkrieg, deep operation, air-ground operation, and interdiction of second echelons remain relevant. Modern methods and tools of warfare, on the one hand, facilitate the implementation of plans within these concepts but simultaneously complicate them. The paradox lies in modern C2 systems, which allow for managing and controlling units, receiving information from them, and supplying them with information from a significant distance from their bases and decision-making centres.

Closing thoughts

Despite major flaws at both the technological and organisational levels, the Russian Armed Forces have shown significant adaptation in some domains. Despite this, many problems remain and the most important factor for Russian troops having some limited offensive initiative is their quantitative advantage, especially in terms of military hardware. Despite the Western military support to Ukraine, Russia has access to Soviet stockpiles of munitions and weapons, many of which are considered low-quality by modern standards, but nonetheless greatly outnumber the assets possessed by their opponents.

In this environment, even the limited positive changes that the Russian Armed Forces were able to gain are affecting the situation on the battlefield. The Ukrainian Armed Forces, which have shown much more initiative in adopting new approaches, are not able to achieve a serious or lasting advantage due to limited resources and the ongoing adaptation of Russian troops, which often copy approaches introduced by Ukrainians – as in the case of FPV drones. Added to this, some of the Russian Armed Forces’ more significant developments, such as improving their reconnaissance-strike capability, in particular with regards to targeting Iskander-M strikes at depth behind the front lines, have proven difficult for Ukraine to adapt to.

Over time, the Russia’s forces will find themselves increasingly unable to rely on older stockpiles of equipment as they deplete. It remains to be seen whether or not the Russian Armed Forces’ continued efforts to overcome their deficiencies have borne meaningful fruit by that point.

Leonid Nersisyan, Samvel Movsisyan, and Vincent Sauve

Leonid Nersisyan is a Senior Research Fellow at APRI Armenia and freelance author who has written for various publications in the defence and aerospace sphere, as well as a business development director at Bootech.

Samvel Movsisyan is a reserve officer of the Armenian Armed Forces and holds a PhD in Technical Sciences. He is an independent analyst in the field of armaments and operational art, and author of the book ‘Countering Precision Weapons Systems in Modern Warfare’, along with various articles. Vincent Sauve is an Intern at APRI Armenia, focusing on geopolitics, defence systems and technologies. He is currently finishing his master’s degree in Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Nanterre University, Paris.

![Ukraine: Russian forces capture key towns [via Ugolok_Sitha Telegram Channel]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Russian-Motorbike-loaded_via-Ugolok_Sitha-Telegram-Channel-Kopie-218x150.jpg)