Pakistan’s journey to defence-industrial self-reliance has been marked by geopolitical challenges and shifting alliances. This article traces the evolution of Pakistan’s indigenous defence industry, highlighting key milestones along its journey from reliance on foreign arms to developing indigenous nuclear and conventional weapon systems.

Upon independence in August 1947, Pakistan faced a significant problem as it attempted to build a sustainable defence structure. True, it had ground, air and naval forces that were well equipped with modern weapons, which had emerged from the partition of the pre-independence military of British India. Unfortunately, although colonial India did have a defence industry and a credible maintenance, repair and overall (MRO) structure, these assets were now not in post-partition Pakistan.

Clearly this was an unacceptable situation for Pakistan, and this resulted in the decision to start a programme to establish a national defence industrial base. Pakistan worked with the Royal Ordnance Factories (ROF) in Britain to establish the first factories of what would become Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF) at Wah Cantonment. Production of 7.7 × 56 mmR small arms ammunition and then Lee Enfield No.4 Mk1 rifle manufacture commenced in 1952. Later, once Lee Enfield production had ceased at ROF Fazakerley in Britain, all the tooling was transferred to the POF, thereby allowing No.4 Mk2 production to commence in 1957.

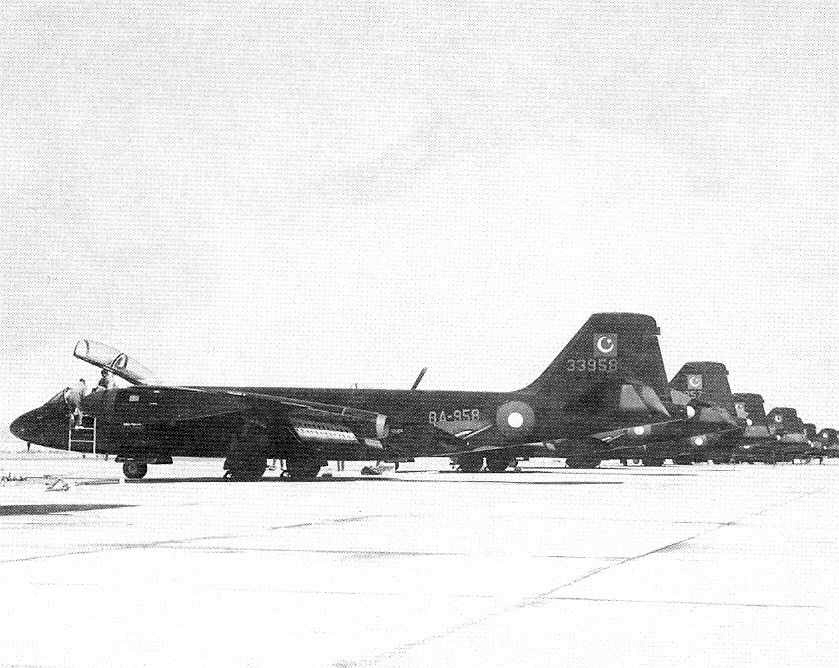

Over the course of the 1950s, Pakistan began to draw closer to the US and this saw them join both the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO). Pakistan also signed up for a Mutual Defence Assistance Agreement with the US in May 1954, which resulted in a substantial amount of military aid being delivered to Pakistan. This aid was absolutely transformative for the Pakistani military throughout the 1950s; the Pakistan Army received 345 M47 tanks, 150 M24 and 50 M41 light tanks, along with 105 mm, 155 mm and 203 mm tube artillery, while the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) received 120 F-86 Sabre fighters and 26 B-57B bombers.

Credit: Pakdef.info, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

The defence relationship with the US was seen as giving Pakistan an effective deterrent against its much larger neighbour, India. US deliveries continued into the early 1960s with the Pakistan Army receiving 200 M48 tanks and 109 M113 APCs and more artillery. Following the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, US military assistance was halted and an embargo on military support was imposed. This was seen as a betrayal by Pakistan and would lead to new defence supply relationships elsewhere and a new emphasis on developing the national defence industrial base.

From the beginning, the primary strategic threat to Pakistan was India; meanwhile China was having its own strategic issues with India, as evidenced by the 1962 Sino-Indian border war. A strong Pakistan was therefore in China’s interest, while Pakistan was at the same time relieved to have a reliable supplier of defence equipment. China provided 200 Type 59 tanks in 1965 – all of which were delivered by 1966. Pakistan also placed an order for 550 Type 59 tanks in 1965, which were delivered between 1967 and 1970; a significant quantity of artillery was also supplied.

The Soviet Union also supplied Pakistan with equipment, but the defence relationship never solidified; instead, Moscow would become India’s primary arms supplier. The end result was that China would become a crucial partner in terms of defence equipment supply to Pakistan, a position it holds still to this day. In the context of the Pakistani defence industry, this influx of Chinese and Soviet equipment operated in tandem with US/NATO pattern equipment, created a situation in which Pakistan had to have the ability to, at a minimum, produce ammunition and basic consumables domestically. The POF had started off producing British small arms calibre munition, and would go on to produce standard NATO calibres in parallel with standard Soviet/Chinese calibres. Today, the POF’s product range covers the majority of NATO and Soviet artillery calibres and the full spectrum of other munitions.

As can be imagined, trying to operate a military force equipped with a highly diverse selection of equipment with limited interoperability is a challenge. The problem for Pakistan was that it was unable to turn to a reliable single supplier or grouping of suppliers to meet its equipment needs. In 1966, Pakistan turned to France to acquire three Daphne class submarines (delivered in 1970) 24 Dassault Mirage IIIEP aircraft ordered in 1967 (delivered in 1969), 30 Mirage 5PA fighter-bombers ordered in 1970 (delivered in 1971/72), followed by ten more Mirage III aircraft in 1975 (delivered in 1977), and finally 32 additional Mirage 5PA aircraft in 1970 (delivered in 1980/83), further complicating interoperability.

Building a deterrent

In the wake of the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War and the loss of what was then East Pakistan (today Bangladesh), the Pakistani leadership found themselves in an incredibly difficult geo-strategic situation. To survive this new reality, Pakistan would need to have an effective deterrent, made even more pressing when India detonated a nuclear device at Pokhran on 18 May 1971, with New Delhi describing this as a “peaceful nuclear explosion”. At that point, it became clear to Pakistan that they would have to develop their own nuclear weapons capability and Pakistan subsequently achieved this aim, but at the cost of suffering extended embargoes by many of its defence equipment suppliers.

Credit: Pakistan Air Force

Concern over Pakistani nuclear efforts led the US to halt military assistance in 1990. An immediate consequence was that 11 F-16A/B Block 15 OCU aircraft that were to be supplied to the PAF under the Peace Gate III programme were embargoed. The follow-on Peace Gate IV programme for 60 F-16A/B aircraft for the PAF was also embargoed, with the 17 already built aircraft put into storage and the remaining 43 aircraft under production subject to a ‘stop work’ order.

The fact that the PAF would not receive these 71 F-16A/Bs represented a major blow. The solution was a major upgrade programme for existing PAF aircraft. Established in the 1970s, the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) located near Kamra was first designed as an MRO facility for Chinese F-6 aircraft. The next step was the opening of the Mirage Rebuild Factory (MRF); this provided life extension and MRO services for the PAF Mirage III/Mirage 5 fleet. In 1990, Pakistan was able to acquire 50 ex-Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Mirage III aircraft from Australia, and went on to acquire second-hand Mirage III/Mirage 5 aircraft from Spain, Lebanon and eventually France throughout the 1990s.

With the F-16s embargoed, Pakistan decided to embark on an extensive upgrade programme for the Mirage fleet – known as Retrofit of Strike Element (ROSE). In the ROSE I programme, the PAC upgraded more than 30 Mirage III and 30 Mirage 5 aircraft; the follow-on ROSE II and ROSE III programmes would cover some 50 aircraft that were subsequently acquired from France. Pakistan would continue to acquire second-hand Mirage III/Mirage 5 aircraft and spares wherever it could, to provide long-term sustainment for the fleet. MRO experience gained with the F-6 and the Mirage fleet, as well as the ROSE upgrade, provided the basis for the PAC to embark on the co-development and production, with Chinese assistance, of the JF-17 Thunder combat aircraft which is being acquired in large numbers by the PAF and being offered for export.

Credit: Pakistan Air Force

Prior to that, Pakistan had acquired the right to the Swedish MFI-15 basic trainer which was produced in Pakistan as the Mushshak; the PAC further then developed it into the Super Mushshak configuration. Initially the Mushshak was acquired to meet Pakistani requirements, but subsequently the Super Mushshak managed to achieve export sales, with customers including Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Türkiye. Of course, export sales for the JF-17 are a much more challenging task, yet sales have already been agreed with Azerbaijan, Myanmar and Nigeria. In addition, a potential order from Iraq has generated much speculation. Into the future, beyond the JF-17, the idea is that Pakistan will be able to design, develop and manufacture a totally indigenous advanced combat aircraft.

Missiles

Returning to the subject of the nuclear programme, the first weapon would be a free fall nuclear bomb, which would be carried by PAF F-16 and Mirage aircraft. However, Pakistan would have to acquire other delivery systems, such as missiles; these would provide a strategic deterrent as well as the option of an extended range conventional strike capability. The Pakistan Army had embarked on the development of a tactical ballistic missile (TBM), the Hatf, with a conventional warhead and range of 70 km. Progress was slow and the impetus to develop a functioning missile grew exponentially, especially after India test launched its Prithvi TBM in February 1988, with its 150 km range. Eventually though, Pakistan did achieve its deterrent objectives. Proof that Pakistan had a nuclear deterrent came in May 1998, when Pakistan conducted six nuclear tests in response to five Indian nuclear tests earlier that month.

The National Engineering & Science Commission (NESCOM), established as the overall authority for major national defence programmes in 2000, has overseen the development of an extensive family of missiles from TBMs, to short-range (SRBM) and medium-range (MRBM) systems, including an MIRV capability. The development of the Babur cruise missile family for the Pakistan Army and Pakistan Navy (PN) followed, and these are available with either nuclear or conventional warheads. The initial ground-launched Babur-1 was followed by the Babur-1A with a 450 km range and the Babur-1B with a 900 km range, both of which were tested in 2021. Alongside these, there is also the Babur-2 variant with a reported 750 km range, and the Babur-3 submarine-launched variant, successfully tested in 2017 and 2018, with a reported 450 km range, and which can be equipped with a nuclear warhead. An anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) variant equipped with a conventional warhead, known as Harbah, has also been developed for the PN.

Credit: Skybolt101, via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

NESCOM has also developed the Ra’ad air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) with a 350 km range for the PAF, which can be fitted with either a conventional or nuclear warhead. The later Ra’ad 2 variant has a 600 km range, and both missiles can be used from PAF JF-17 or Mirage aircraft. Other NESCOM origin air weapons include the H-2 guided glide bomb with a 60 km range, and H-4 guided glide bomb with a range of 120 km, along with Hafr anti-runway bombs. NESCOM also manufactures UAVs.

Another Pakistani state-owned entity active in the missile, rocket and air weapons area is Global Industrial Defence Solutions (GIDS). They have developed the Taimur air-launched cruise missile, with a 290 km range, and produce the Takbir range extension kit (REK) for conventional gravity bombs, which converts them to GPS-guided glide bombs. The company also produces the Anza man-portable air defence system (MANPADS) family derived from the Chinese QW-2 design, and the Baktar Shikan anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) derived from the Chinese HJ-8 design. More recently GIDS introduced the Fatah I (140 km range) and Fatah II (400 km range) Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS). The company also produces UAVs.

One significant programme being developed at GIDS is the Faaz missile system. Allegedly based on the Chinese SD-10 (PL-12) radar-guided medium-range air-to-air missile (MRAAM), the Faaz will be available in several variants: the Faaz-RF (with an active radar seeker) and Faaz-IIR (with an imaging infrared seeker) for air-to-air applications, both with a range of over 100 km, and the Faaz-SL for surface-launched applications, with a maximum range of 20-25 km and maximum altitude of 6-8 km. GIDS also offers the newer Faaz-2 air-to-air missile, which according to the company will have a range of 180 km range and will be offered with RF and IIR guidance. Also under development at GIDS is the LOMADS air defence system, which is described as a “fully autonomous self-propelled truck mounted system”. The range is between 7 and 100 km, altitude coverage is 30 m to 20 km, with the system capable of engaging 12 targets simultaneously.

Naval sector

In the naval sector in Pakistan the key strategic asset in both naval and commercial shipbuilding is the Karachi Shipyard & Engineering Works (KSEW). Pakistan’s objective has been to improve the capabilities of KSEW by adding technology transfer and local production requirements to naval programmes. For example, in the early 1990s, the PN contracted for three Khalid class (Agosta–90B) submarines from DCNS (now Naval Group) in France. The first unit was built in France, the second was assembled at KSEW and the third built entirely at KSEW. In 2011, KSEW was responsible for the retrofit that added an air-independent propulsion (AIP) capability to all three boats.

The PN decided to acquire a new diesel-electric attack submarine (SSK) class in 2015, with eight Hangor class, the S26 export derivative of the Type 039B design. With four units being built in China and four at KSEW, the keel was laid for the first KSEW unit in December 2022 and for the second unit in February 2024. Other programmes with China have included the Zulfiquar class frigate (Chinese designation F-22P), with three units built at Hudong-Zhonghua in China, with unit number four, PNS Aslat, being built at KSEW and commissioned in 2013.

Credit: ISPR Pakistan

The naval relationship between Pakistan and Türkiye is an important development for both the PN and KSEW. One aspect of this was the 17,000-tonne displacement fleet replenishment tanker PNS Moawin, commissioned in 2018. The tanker was built at KSEW to a design from STK in Türkiye. More recently, the PN decided to acquire four MILGEM corvettes from Türkiye, classified as the Babur class by the PN; the first two units were built in Turkey, with the second two, PNS Badr (launched May 2022) and PNS Tariq (launched August 2023) built at KSEW.

The most ambitious future naval programme between Türkiye and Pakistan is the Jinnah class frigate. The frigate will be jointly designed by ASFAT in Türkiye, who were responsible for the MILGEM corvettes, and a PN design team. In total, the PN intends to acquire six of these multipurpose frigates and all will be built at KSEW.

Armour

Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT) is an important capability in the land systems sector of the Pakistani defence industry. In the 1990s, HIT licence produced the Chinese Type 85 tank. The next step was to produce a more advanced tank more suited to Pakistan Army needs, with the Chinese Type 90-II (VT-1A export designation) tank chosen as the basis for the Pakistani tank produced at HIT as the Al Khalid, which was followed into production by the improved Al Khalid variant. Mention should also be made of the Al Zarrar tank programme, a comprehensive upgrade programme for the Type 59 tank, with more than 500 tanks upgraded.

Credit: ISPR Pakistan

In March 2024, HIT unveiled the first new Haider main battle tank for the Pakistan Army, based on the Chinese VT-4 export design, modified for Pakistani requirements and produced at HIT. Reportedly the Pakistan Army could acquire as many as 679 Haider tanks to replace legacy vehicles. Some years ago, Pakistan produced a number of M113 vehicles from US-supplied kits; after further supplies from the US were embargoed, they began building their own M113 version, the Talha APC. Other variants have been developed on the basis of the Talha, including the Sakb command vehicle variant, the Maaz anti-tank variant (armed with a single Baktar-Shikan ATGM launcher), and the Mouz air defence variant (armed with a single RBS 70 missile launcher). HIT also developed a stretched subfamily with six roadwheels instead of five; versions include the Saad APC, the Al Qaswa logistic vehicle and the Al Hadeed armoured recovery vehicle (ARV). HIT has also conducted rebuild programmes on Pakistani M113 and M109 vehicles, and they also have a gun barrel manufacturing capability from 105 mm to 203 mm, including 125 mm smoothbore barrels.

David Saw

![BVRAAMs: Closing the horizon This photo showing a piece of the wreckage of an Indian Rafale, serial number ‘BS 001’, showed up on social media shortly after the IAF’s night operations of 6/7 May 2025. [Vigorous Falcon X Account]](https://euro-sd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Rafale-Wreckage-Piece_Vigorous-Falcon-X-Account-Kopie-218x150.jpg)