The Baltic Sea is becoming a significant geographic space in NATO-Russia naval rivalry. For NATO, its new Baltic member states – Finland and Sweden – add value in this context, bringing Baltic-specific capability, experience, and expertise to the contest with Russia in the region.

The Baltic Sea sits centrally in the contemporary naval competition between NATO and its navies and the Russian Federation Navy. Here, these actors play significant roles on what has become a central stage in the wider Euro-Atlantic theatre’s security balance. While the ongoing Russo-Ukraine war, which erupted in February 2022, has developed largely as a land-focused conflict, the Baltic Sea (towards NATO’s northern flank) – and the Black Sea (on NATO’s southern flank) – are maritime regions into which events surrounding the war have spilled.

At a military-operational level, the occurrence since the war broke out of four critical undersea infrastructure (CUI) security incidents in the Baltic indicates that hybrid, asymmetric warfare campaigns may be underway there, designed to undermine Western connectivity and economies.

In September 2022, two Nordstream gas pipelines were ruptured by explosions, off Denmark’s Bornholm island. In October 2023, the BalticConnector gas pipeline and nearby communications cables, all running between Estonia and Finland, were damaged. In November 2024, the Arelion internet cable linking Sweden’s Gotland island to Lithuania and the C-Lion 1 telecommunications cable connecting Finland and Germany were cut. In December 2024, the EstLink2 power cable plus several internet cables, again all running between Estonia and Finland, were damaged.

In the last three cases, the damage has been attributed to ship anchors being dragged across the seabed. Chinese and Russian commercial ships, present in the areas and at the times concerned, have been cited in the resultant political and public debates as potentially being involved. Yet the density of shipping in the area and CUI on the seabed offers plausible deniability for any rogue actor targeting CUI with ‘shadow fleets’ in hybrid, asymmetric operations.

Following the EstLink2 incident, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte said on social media that “NATO will enhance its military presence in the Baltic Sea.” In response to the incident, but no doubt aimed at tackling the wider Baltic CUI threat, NATO announced in January 2024 the establishment of a new activity – ‘Baltic Sentry’ – designed to deter attempts by state or non-state actors to damage Baltic Sea CUI. The activity is led by Allied Command Operations, with Joint Force Command Brunssum and NATO Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM) running the multi-domain maritime activity, based around NATO’s standing naval forces at the tactical and operational levels.

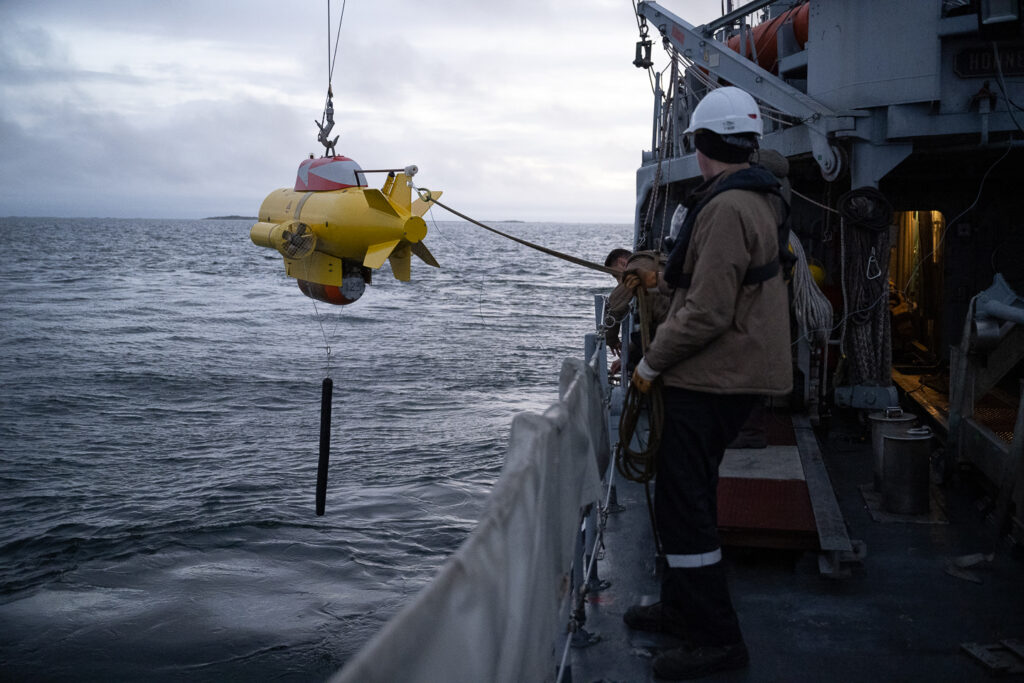

Alongside the CUI incidents, other at-sea developments also underscore the Baltic’s military-operational importance, in a manner that in turn underlines its geostrategic significance. For example, in November 2024, MARCOM established a new anti-submarine warfare (ASW) exercise dedicated to Baltic Sea operations. Exercise ‘Merlin’ – conducted off Sweden, with 10 NATO countries participating plus MARCOM’s North Atlantic-focused Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 (SNMG1) – is designed to enhance NATO’s knowledge of the region’s underwater operating environment and build its wider regional maritime situational awareness (MSA), while also demonstrating ASW presence and readiness to build collective deterrence and defence in the region.

‘Merlin’ illustrates how NATO was already enhancing its Baltic Sea military presence. The exercise’s geostrategic importance is underlined by the fact that MARCOM now conducts an annual, high-level ASW exercise in each Euro-Atlantic theatre region, with ‘Dynamic Manta’ and ‘Dynamic Mongoose’ occurring in the Mediterranean and Norwegian seas, respectively.

In RUSI’s annual Gallipoli Memorial Lecture, held in October 2024, Admiral Sir Keith Blount – a UK Royal Navy (RN) officer posted as NATO’s Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe (DSACEUR), having previously served as Commander (COM) MARCOM – said “Sweden and Finland bring with them considerable military capability. Moreover, the Baltic Sea area looks very different with them as members …. [It] has become a formidable geographic cornerstone for the alliance.”

Yet while NATO needs to support and secure Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as its Baltic State allies plus Finland and Sweden as new members, the Baltic is also a ‘strategic sea’ for Russia, which needs maritime access between Kaliningrad and St Petersburg.

Winds of change

One long-established NATO route for enhancing regional presence is joining national exercises. Following Finland’s and Sweden’s accession, NATO is already building Baltic presence this way.

In November 2024, two of MARCOM’s four standing naval forces – SNMG1 and Standing NATO Mine Counter Measures Group 1 (SNMCMG1) – joined the Finnish Navy-led Exercise ‘Freezing Winds 2024’, in the eastern Baltic. ‘Freezing Winds’ is the navy’s largest exercise, involving all its assets and personnel; participation included 15 NATO countries, 30 surface ships, plus maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) and marine forces.

“‘Freezing Winds’ is a crucial component of the alliance commitment to security in the Baltic Sea region,” Commodore Janne Huusko – Finnish Navy Command’s Chief of Staff – told the exercise’s media briefing, onboard the Royal Norwegian Navy auxiliary ship HNoMS Maud, in port at Turku, southwestern Finland. “The Baltic Sea is now more strongly defended since Finland and Sweden joined NATO, increasing stability and security in the area.”

“The objective of ‘Freezing Winds 24’ is to train for the execution of international naval operations in the circumstances of the Finnish coast and the Baltic Sea,” Cdre Huusko continued. “The exercise provides an excellent opportunity to highlight the presence, readiness, and partnership of participating countries in light of the current and future challenges related to joint, combined, and multinational operations, and within the framework of the international security architecture.”

The exercise encompassed broad operational training, including amphibious warfare, maritime security, and sea lines of communication (SLOCs) protection. It tested and built participants’ capabilities, readiness, and command and control (C2). Noting the exercise’s wider impact on NATO operational output, Cdre Huusko said “Together, we will strengthen our capabilities to secure maritime trade routes, protect SLOCs, and uphold freedom of navigation in the Baltic Sea.”

The importance of the opportunity presented for NATO to practice and demonstrate integration with one of its newest members in the challenging Baltic operational environment was underlined by the two NATO task groups’ presence.

SNMG1 was deployed in the Baltic conducting naval surveillance operations, contributing to NATO vigilance activities. “We do this by patrolling the sea to observe and establish a clear picture of what is going,” said Cdre Rasmussen. “We normally focus on the North Atlantic area, and for the time being we are patrolling in the Baltic Sea region. That is a very important strategic region for NATO.”

“The Baltic region is not just a maritime domain: it is a key component of NATO’s broad defence strategy,” Cdre Rasmussen continued. “Our operational presence here underpins our commitment to maintain security and enhance deterrence, and is demonstrating NATO resolve to protect the territorial integrity of all our allies.”

SNMG1’s presence in and around the Baltic Sea for much of 2024 underlined the region’s current strategic significance for NATO. SNMG1 – as MARCOM’s North Atlantic-focused, destroyer/frigate-based standing naval force – has a vast geographic area of responsibility (AOR), covering the North Sea and Eastern Atlantic, the Norwegian Sea, the Arctic Ocean, and the High North. Yet, with the Russo-Ukraine war bringing greater strategic and operational focus on the central front ashore and the Baltic and Black seas as the conflict’s maritime flanks, so SNMG1 is spending increasing amounts of time in the Baltic – including to quickly integrate Finnish and Swedish naval forces more fully into alliance operations.

“We still have a lot to do in the North Atlantic and elsewhere, but we are focusing on the Baltic, and training – especially with Sweden and Finland – is a key objective for us,” Cdre Rasmussen told ESD, onboard Maud. “So, we have increased focus on the Baltic, for good reason.”

Exercises like ‘Freezing Winds’ enable NATO navies to practice integration in real-world operational environments. “[They do] help because we have to do it for real. It’s only when we actually have ships at sea, aircraft flying, and people on the ground that we see all the tiny little bits that need to work together,” Cdre Rasmussen told ESD. Such integration includes the different assets brought by NATO states, including those operated by the Finnish and Swedish navies that offer Baltic-bespoke capabilities. “The ability to operate fast patrol boats and mine hunters on the Finnish side together with the advanced frigates in SNMG1 is absolutely critical,” Cdre Rasmussen added.

Total defence

Events in the Baltic and elsewhere across NATO’s AOR are shaping Finland’s and Sweden’s defence plans. This is shown in Sweden’s 2025-30 Total Defence Bill. Revealed in October 2024 and approved by parliament in December 2024, details of the Bill include increasing defence spending by 2028 to 2.8% of GDP (above NATO’s 2.5% target). In a statement, Sweden’s defence ministry described the Bill as adding “some muscles” to the “skeletal framework” provided in the two previous bills, helping “to accelerate the pace of rearmament” and meeting Sweden’s ambition to be a “credible, reliable, and loyal ally”.

The statement pointed to Russian activities in and around Ukraine, including its hybrid operations and targeting of civilian infrastructure. It highlighted several core capability developments for the navy, which underscore the Baltic naval threat. First, a mid-life upgrade on the five in-service Visby class corvettes, which will occur within the Bill period, will add an anti-air warfare missile capability. Second, Sweden will expand and re-organise its coastal missile capabilities – operated by its marine forces, and including anti-ship missile capability – into two units to improve availability. Third, procurement of the new Luleå class surface combatants will commence.

Overall, the statement noted, NATO’s capability targets provide an “important starting point” for how Sweden will build its defence organisation and capability. The Bill’s maritime elements reflect a wider re-think of Sweden’s maritime strategy, which is taking place within the defence ministry in the context of reviewing how all elements of Sweden’s society combine to deliver the country’s ‘Total Defence’ construct.

“There are many reasons why a new maritime strategy has to be produced. Two of the main reasons are: the current security situation in the surrounding world; and our membership of NATO,” Brigadier General Patrik Gardesten, the Royal Swedish Navy’s (RSwN’s) Deputy Commander, told ESD in a November interview. “We acknowledge the NATO ‘360’ perspective,” he added: “We will contribute to alliance tasks and meet the threats wherever they occur.”

“We also bring to the table our military geography,” Brig Gen Gardesten continued. “Sweden’s territory together with Finland’s territory is a real game changer for the alliance up in the Northeast flank, [including] to be able to defend it and sustain it.”

Strategic SLOC security

Providing sustained defence of NATO’s new geography in the Baltic includes securing SLOCs, part of which is the CUI network. The recent CUI incidents illustrate the complexity of the Baltic’s SLOCs network (surface and seabed), NATO’s increased focus on Baltic SLOC security at alliance and member state levels, and the competition between NATO and Russia over access to surface SLOCs.

For Finland, 94% of its trade travels by sea in peacetime. For NATO, in crisis or wartime, there may be a need to support or reinforce by sea various regional territories, including the Baltic States, Finland itself, or Swedish islands. For Russia, up to 60% of its trade is carried across the Baltic. So, especially in times of crisis, Baltic waters are congested and contested.

“Protecting SLOCs is vital for Finland. Finland is often described as an island from the import or export viewpoint. Maintaining the functioning of our society is heavily based on the maritime transport of goods,” Cdre Huusko told the briefing. SLOCs security is a core task for the Finnish Navy, something it must tackle with national authorities and NATO allies, he added.

From Sweden’s perspective, Brig Gen Gardesten explained, “The country is totally dependent on freedom of navigation in its surrounding waters, the SLOCs, and the functionality of our harbours and sea ports of embarkation.” This applies to every country in the region, he added.

For NATO and its navies, Baltic SLOCs protection is an increasingly significant task. “We must train hard in a challenging and realistic environment to be able to defend our borders, our countries, and deter aggression if and when needed. To this end, control of the sea is very important for NATO in peace as well as in wartime,” said Cdre Rasmussen. “We need to protect the SLOCs.”

Integrated into this complex geophysical environment is an intricate CUI network. Broadly, CUI includes oil and gas resource pipelines and other installations; communications, data, and power cables; environmental and military sensors; wave and wind power structures; scientific research nodes, including oceanographic and hydrographic installations and instrumentation; and facilities for accessing sub-seabed critical minerals.

The Baltic’s CUI risk is pronounced. As demonstrated in Ukraine, Russian wartime campaign strategy includes targeting civil energy and other infrastructure. The four Baltic CUI incidents underscore the MSA challenge in monitoring ‘shadow fleets’ in shallow, busy waters that mask their activities. These incidents underline the emerging, now enduring, risk to CUI that is economically significant for the region and more widely, and the consequent fact that Baltic Sea CUI is now a strategic SLOC.

The operational and strategic significance of this issue was underlined in January 2025 when six countries – Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Poland, Sweden, and the UK (under the auspices of the Joint Expeditionary Force maritime operational partnership, of which they are all members) announced plans – under Operation ‘Nordic Warden’ – to monitor ‘shadow fleet’ ships seen as presenting a risk in key CUI areas. ‘Shadow fleet’ ships are suspected of helping Russia circumnavigate oil export sanctions, and are central in NATO navies’ focus on shipping that could be conducting Baltic CUI attacks. The decision to stand up the operation followed the EstLink2 incident; in December 2024, the six countries had already indicated they may start checking on ‘shadow fleet’ vessels transiting regional choke points like the Dover and Kattegat/Skagerrak straits. In late 2024, as reported in Western media, the Danish defence intelligence service warned that Russia could start assigning naval escorts to such shipping.

Baltic planning

The Baltic’s growing importance for NATO strategy and operations was further underlined in October 2024, when the German Navy established a new tactical maritime headquarters, Commander Task Force (CTF) Baltic.

Responding to NATO’s broader initiative to bring regional countries together to strengthen collective defence in regions across the Euro-Atlantic theatre, and alliance directives for member states to establish high-level tactical maritime headquarters, CTF Baltic will take on tasking on behalf of MARCOM in its maritime area; coordinate allied Baltic Sea naval activities; and conduct tactical control of maritime forces.

CTF Baltic is a German Navy national headquarters that can perform NATO tasks. Staff officers are drawn from Germany and other NATO allies (and not just Baltic member states). Its staff participated in ‘Freezing Winds’, engaging particularly in the integrated, tactical control of NATO maritime forces.

CTF Baltic’s establishment illustrates the reciprocal learning process between NATO and regional allies. First, CTF Baltic illustrates how NATO is looking to improve coordination of regional member state naval activities, command of regional operations, and regional response plans now that Finland and Sweden are members. Second, its presence reflects the need for Finland’s and Sweden’s national defence plans to be aligned and integrated with NATO’s, including the alliance’s vigilance activities and wider regional response plans.

“As Sweden is now a NATO member, we are included in and can affect the regional planning,” said Brig Gen Gardesten. “We can affect that using our experience in the region; our territory, for instance how we use our archipelago for protection or how we use our naval bases for logistics; and our expertise, for instance in the subsurface domain.”

“From the NATO perspective, with Finland’s and Sweden’s territory and capabilities being part of NATO’s capabilities and assets, we have to take that into account in the regional plans,” he added. “From the Swedish perspective, we have to see the possibility that our forces, capabilities, and territory can be used, for instance to ensure reinforcement of [NATO] states.”

Noting that maritime infrastructure security in Sweden is a civil sector responsibility, as well as the broader fact that Sweden – as previously non-aligned – has developed full, society-wide responsibility for national security under its ‘Total Defence’ concept, Brig Gen Gardesten said that ensuring freedom of navigation in its waters, for example, is more than just the RSwN’s responsibility. The ‘Total Defence’ approach might thus be something Sweden could bring to the table for NATO to consider in developing future defence plans, he added.

Collective value added

The Finnish and Swedish navies add value for NATO in the Baltic in several ways, including: bringing expert understanding of the operational environment; building a detailed recognised maritime picture (RMP) and wider MSA; and exploiting these two with Baltic-focused operational capabilities.

As regards understanding the Baltic, “This environment is unique …. We know the environment, we know the weather, we know the geographical features in the area. So, this is what we can provide for our allies when they are operating in this part of the world,” Cdre Huusko told ESD. “At the same time, when our allies come here, we are able to join together what we know, so we are even stronger based on that cooperation.”

Brig Gen Gardesten reiterated the impact the regional navies’ sustained at-sea surveillance presence has for NATO. “To have a credible RMP, like we have today, we really, really need to be out at sea every day and to establish MSA, to have it nationally but also to contribute to MARCOM’s regional MSA,” he said.

Yet maintaining this surveillance presence while supporting NATO taskings may require the navy to reconsider its force structure size, Brig Gen Gardesten continued. “The Swedish Navy needs more hulls. We need them because we have to be able to continue our sea surveillance operation, and we have to be able to conduct naval operations in several directions – not only in one direction, like we have been for many years.”

For the RSwN now as a NATO member, one such new direction may be out into the North Sea. The new Luleå class surface ships will enhance the navy’s capacity and capability to operate there.

As regards capabilities, the two navies have built Baltic-focused outputs. For the Finnish Navy, this includes its mine counter-measures (MCM) vessels. For the RSwN, in ASW it provides Baltic-optimised capability for hunter and hunted: its Visby corvettes bring stealth and high speed; its A19 Gotland class diesel-electric submarines (SSKs) are highly manoeuvrable, and extremely quiet at low speed.

On ‘Merlin’, SNMG1 exercised with the RSwN and one of its A19s. “To find submarines in the Baltic is very demanding, because of the conditions,” Cdre Rasmussen told ESD. “We saw, however, that our frigates – together with the Swedish corvettes, helicopters, and MPAs – were a good match against the submarine.”

Reflecting this point, Brig Gen Gardesten said that, with Sweden having been working closely with NATO for several decades including (since 1994) in the ‘Partnership for Peace’ programme, it has good understanding and use of NATO TTPs, leaving broader connectivity as the most significant hurdle remaining. “It’s all about connectivity. We have to, together with our allies, develop common communications systems, and we have to develop our ability to share information,” he said. “We do that today, but we have to be better at sharing information in other systems in order to be able to conduct combined operations, and not just coordinate operations.” Improved information sharing will also improve regional MSA, he added.

Both the Finnish and Swedish navies plan to deploy ships with the standing naval forces in 2025. The addition of two more member state navies deepens the platform pool available to MARCOM to fill these forces.

Both navies are also building new – larger, and more capable – platforms that will add further value for NATO in the Baltic, and more widely. For Finland, four Pohjanmaa class multi-role surface combatants, being acquired under the ‘Squadron 2020’ programme and scheduled for delivery by around 2029, will provide anti-surface, anti-submarine, anti-air, and mine-laying capabilities. For Sweden, its four new Luleå class surface ships, scheduled for delivery in two pairs (before 2030 and before 2034), are designed to enhance RSwN capacity to support NATO requirements. The navy will also receive two A26 Blekinge class SSKs in the 2029-30 timeframe, with more maybe following.

Balancing act

As the Finnish and Swedish navies and NATO learn more about each other, future operational developments seem likely to involve balancing generation of presence and capability in the Baltic and more widely across the Euro-Atlantic theatre. The Russian threat in the Baltic underlines the need to maintain deterrence and defence there, while NATO navies operating ‘out of area’ in other regions of the alliance’s AOR demonstrates wider cohesion.

Such wider presence could add more value for NATO. “We can bring something to the table in other areas,” said Brig Gen Gardesten. “For instance, in the future, Swedish MCM capabilities could be useful in the Black Sea and waters in that area.” Such capability, he continued, could include operational concepts, personnel expertise and advice, and physical presence of MCM vessels (including within MARCOM’s Mediterranean-based MCM standing force, SNMCMG2).

However, such ideas and options will need to be balanced against Baltic commitments, where RSwN presence and expertise will be paramount. “It’s always about priorities,” said Brig Gen Gardesten. “Now that we are NATO members, we are around the table when these priorities and these decisions have to be made.”

Yet bringing Baltic-specific capabilities and expertise and contributing to NATO operations more widely both add value for the alliance, Brig Gen Gardesten explained. “When we contribute and exercise together, we make NATO stronger because we contribute with capabilities that no other country, in some ways, has. We also send a very strong signal to Russia that we, every day now, increase our capability to conduct operations together, within the framework of NATO,” he said. “So, we learn, we integrate, we increase interoperability, we work on better connectivity – but we also send a signal that ‘stronger together’ is something for Russia to count on.”

Dr Lee Willett

Author: Dr Lee Willett is an independent writer and analyst on naval, maritime, and wider defence and security matters. Previously, he was editor of Janes Navy International, senior research fellow in maritime studies at the Royal United Services Institute, London, and Leverhulme research fellow at the Centre for Security Studies, University of Hull.