There are many lessons to be learnt from the logistics of the war in Ukraine. Quite a few relate to how we need to adapt to modern warfare and how to prepare our economies for a complex landscape of challenges. For starters, the equipment providers often lacked direct access to the battlefield to train personnel, and organise storage, maintenance and repair.

Secondly, the equipment used by Ukraine reflects disparate industrial bases and equipment logistics processes. In the face of these challenges, the pace at which Ukrainian forces have had to integrate a diverse array of equipment and support processes has been extremely fast. While this was fairly ad-hoc at the start of the conflict, it has become increasingly efficient.

NATO’s website succinctly summarises logistics as relating to “having the right thing, at the right place, at the right time,” and serving as a “bridge between deployed forces and the industrial base”. Yet despite its importance, the topic often receives less attention than other areas until times of crisis arise. A common characterisation of its practitioners, taken from a text known as the ‘Logistician’s Lament’, which is most commonly attributed to an unknown author goes as follows: “Logisticians are a sad, embittered race of people, very much in demand in war, who sink resentfully into obscurity in peace.” This obscurity was probably the case for thousands of logisticians who, during the ‘peace dividend’, and behind the obscurity of their desk, carefully planned and implemented maintenance and sustainment of the bulk of equipment that is now used in Ukraine. Today, these same logisticians are probably unsurprised by many of the ‘lessons learned’ from the ensuing war.

The Tip of the Iceberg

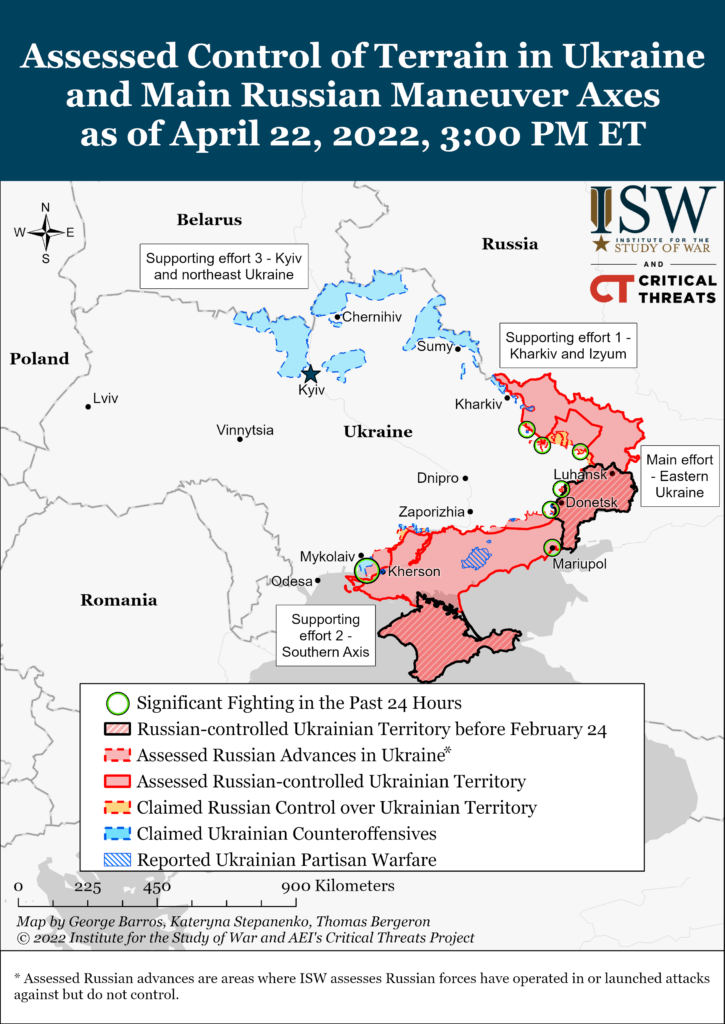

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, public attention was focused on tactics used by both parties to enable their own movement of forces and equipment while disrupting those of the adversary. The invasion and annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, which hosts several Russian military bases, had already given Russia significant advantage, with Sevastopol allowing control of shipping routes. Before and during the current conflict, Russia sought to build land connections with Ukraine, important for movement and for sustainment. The opening of the Kerch bridge in 2018, which linked Russia to Crimea by both road and rail, was another advantage which existed before Russia’s 2022 invasion.

The fight to control the Donbas Region, the battles of Kherson, of Mariupol, or of Zaporizhzhia are also believed by analysts to have been strategic efforts for Russia to establish a ‘land corridor’ linking the Crimean Peninsula to the two rebel regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, and ultimately to Russia. Control of these strategic locations provided access to critical infrastructure – railways, water, energy – as well as to key industrial resources.

Control of other critical infrastructure assets, or even of ‘vulnerabilities’ like the Chernobyl powerplant, were meant to disrupt Ukraine’s supply routes and access to critical infrastructure necessary for the sustainment of forces and of population.

Credit: Ukraine Security Service (SSU)

In retaliation, Ukrainian Railways terminated relations with Russian Railways and destroyed the railway line between the two countries. Russia encountered several logistics challenges along the way. The 64 km long traffic jam caused by a military convoy near Kyiv in March 2022 was the beginning. Its logistics vehicles were frequently targeted, leading to Russian combat vehicles running out of fuel and having to be abandoned. Despite these problems, for over a year now both parties seem to persist in their military efforts, in the face of expectations.

Ukraine’s highly competent defensive response led Russia to face a number of difficult choices, after having lost a lot of equipment in the first two months when it was understood to have planned for a rapid military operation with little resistance from the Ukrainian side. Although Ukraine’s armed forces have performed well, they have often needed significant materiel support from abroad to even maintain parity with Russia in various sectors, let alone achieve operational superiority. However, the intensity of the conflict is such that it has led to stocks of many crucial supplies running low, notably including artillery ammunition.

It is easy to understand that providing materiel support to Ukraine was and still is a mighty task that goes beyond simply moving equipment from point A to point B. It involves human resources and training of personnel, positioning and protecting stockpiles, as well as the capacity to maintain and repair the equipment received. These challenges cover the entire spectrum of logistics.

Credit: Institute for the Study of War

A Variety of Suppliers and Equipment

According to the Wikipedia ‘List of military aid to Ukraine during the Russo-Ukrainian War’, approximately 45 countries have provided equipment and other forms of aid to Ukraine, as well as to the European Union, private companies and other parties. The level of coordination required must be daunting, as it involves all levels, not just the political level. Nonetheless, it was pivotal in establishing a structured approach and gradually overcoming initial maintenance and training limitations.

Since the start of the Russian invasion, Ukraine welcomed all support but insisted on “urgent requirements”, dictated by the reality on the ground. From this perspective, decision-making process and coordination was probably perceived as relatively slow by Ukraine, since it often urged EU and NATO countries to move faster in fulfilling their promises.

The supply of ammunition and of Western tanks are the best-known examples of how reality on the ground dictates certain urgent requests, and the time needed to implement these requests, both politically and operationally. After months-long insistence by Ukraine, at the beginning of the year, several western countries announced that they would provide Ukraine with main battle tanks (MBTs). Quoting President Joe Biden, tanks were requested because “They need to be able to counter Russia’s evolving tactics and strategy on the battlefield in the very near term. They need to improve their ability to manoeuvre in open terrain. And, they need an enduring capability to deter and defend against Russian aggression over the long term.”

As such, in January 2023, the US has announced it would provide 31 M1A1 Abrams tanks to equip an entire tank battalion, together with training on logistics and maintenance. Added to these, the UK committed to send 14 Challenger 2 tanks, with training of Ukrainian tank crews reportedly completed in March. France agreed to send AMX-10 RC fire support vehicles to the Ukrainian forces, although Ukraine’s initial request was for Leclerc tanks. After some tergiversation, Germany also approved the export of 18 Leopard 2A6 MBTs from the Bundeswehr’s stocks, and several other users announced they would provide Leopard 2 family MBTs from their own stocks.

Credit: EU EAS/EUMAM Ukraine

Regarding ammunition, the Council of the EU reached an agreement in March 2023 to respond to this urgent requirement. A three-track approach was decided to speed up delivery and joint procurement to provide one million rounds of artillery ammunition for Ukraine over the next twelve months. The first part of the Council agreement was marked on 13 April 2023, when the Council announced an assistance measure worth EUR 1 Bn under the European Peace Facility (EPF) to reimburse member states for ammunition donated to Ukraine, whether from existing stocks or from redirecting existing orders.

In addition to these actions, the G7 Leaders’ Statement of 12 December 2022 also emphasised coordination with regards to Ukraine’s urgent requirements, “with an immediate focus on providing Ukraine with air defence systems and capabilities.”

While ammunition and tanks are the most recent and publicised examples to illustrate the wide variety of equipment and sources, many others exist, with each having different degrees of complexity when it comes to logistics, especially maintenance and repair.

Beyond the Political Level, Coordination and Adaptation is Key at all Practical Levels

Regulations and Procurement Instruments

The approvals needed for the re-export of Leopard 2 tanks are also a reminder of the complexity of export regulations, as well as other administrative procedures and certification processes that govern the transfer and export of defence-related equipment. These various regulations are mostly national, and the experience with Ukraine has yielded some hints that export control processes and other regulations could be better-coordinated among allies.

As it may be expected, given the bulk of equipment delivered to Ukraine and the number of procurement authorities involved, the administrative effort on the Ukrainian side must be significant. Ukraine provided several ‘urgent requests’ that the Western countries tried to meet, in many cases after necessary national and multilateral political coordination. Once political agreement is achieved, the true logistics work begins. However, in the majority of the cases, procurement and delivery is done through countries’ own national instruments and procurement procedures, sometimes by providing from national stocks and sometimes by procuring from industry. For example, the US Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) allows the US to procure and deliver to Ukraine directly from industry instead of drawing down from DoD stocks. The EU three-track plan proposes a dual approach to providing equipment, which includes both drawing down from countries’ stockpiles and purchases from industry in the short term, and over the longer term aims to ramp up overall production capacity.

The question is whether these multiple procurement instruments and procedures can be simplified given that equipment is supplied by different countries and multiple actors are involved.

Maintenance and Repair

To be able to use and maintain diverse equipment, coordination is needed with several parties – procurement authorities, industry, users – sometimes in parallel tracks since supply chains may be multiple and even severely challenged. Moreover, in some cases, manufacturing capacity may be insufficient to keep up with the pace of requirements.

The M777 155 mm howitzers and related ammunition were among the first critical pieces of artillery equipment delivered to Ukraine, and led to some of the first lessons to be learnt regarding the organisation of maintenance and repair in high-intensity combat scenarios. The M777, along with other NATO-standard howitzers, and a variety of other equipment can suffer from overuse, prompting a need to improve maintenance strategies in this type of conflict. In conditions where repair facilities in Ukraine can easily become a target, the challenge facing both Ukraine and its equipment suppliers is finding suitable alternatives and/or innovative solutions to protect logistics facilities and stockpiles.

In a similar vein, according to the Polish Defence Minister Mariusz Błaszczak, the main problem in supporting Ukraine with Western tanks is spare parts. As reported by Polsat News, discussions between Minister Błaszczak and German Minister of Defence Boris Pistorius were planned on the margins of the EU defence ministers meeting in Stockholm to address this issue in relation to the Leopard 2 tanks. In March 2023, the Błaszczak also announced that Poland was ready to launch a service hub on its territory for the repair and service of Leopard 2 MBTs delivered to Ukraine. This was confirmed in April on the margins of the NATO Defence Ministers meeting in Ramstein, when Germany, Poland, and Ukraine signed a maintenance agreement. The hub is located at the Bumar-Labedy Machine-Building Plant in Gliwice, and is expected to officially commence servicing and repair operations in May 2023. Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki also announced on 26 April 2023 that the production of Krab 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (SPHs) would take place at the same site.

Credit: Polish MoD

According to Reuters and other press sources, Rheinmetall is planning to set up a “service hub” in Romania to maintain the operational readiness of Western combat systems being used in Ukraine.

Standardisation and Interoperability

The full picture of the required maintenance and repair hubs for Ukraine’s equipment is unknown for operationally sensitive reasons, but given the diversity of equipment, is it likely to be complex and distributed. From this point of view, the Ukrainian experience is the most practical reminder of what has been constantly repeated at the NATO and EU levels for more than 20 years – “avoid duplication” and “promote interoperability and standardisation”.

The diversity of equipment provided to Ukraine is also a test of the extent and limitations of interoperability and standardisation. It is probably only after end of the conflict that the full picture of lessons learned here will emerge. Although much of the NATO countries’ equipment is compatible, it does not mean that all equipment is standardised and interoperable. For example, compatibility issues with ammunition from other NATO countries were reported for 155 mm artillery ammunition, and ammunition supply issues arose following Switzerland’s ban on exporting 35 mm ammunition for the Gepard self-propelled anti-aircraft gun (SPAAG).

Although useful, it should be noted that it does not makes sense to standardise everything. The September 2022 meeting of the National Armaments Directors from member states of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, recognised the importance of standardising systems and munitions to create more interchangeable and interoperable systems. However, it was also suggested by Dr William LaPlante, the US Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, that standardisation needs to be primarily secured “where it makes sense”, such as the 155 mm artillery rounds for the M777 howitzer.

Credit: US Department of Defense

Stockpiling

Like in other sectors, the ‘just-in-time’ production strategy has also proven its limitations in the defence sector. After the Cold War, stockpiling became rather unpopular because it was considered expensive to maintain and encouraged overproduction. Stocks of ammunition and spare parts were reduced, and strategies were implemented to ensure production and supply were conducted in a more cost-effective manner. While achieving cost-effectiveness and avoiding overproduction should remain an objective, the strategies to do so should probably be revised, and should include cost-effective stockpiling.

Logistics Strategies

Logistics doctrines and concepts need to be adapted to the realities and tools of modern warfare – long-range precision fires, drones and other surveillance and target acquisition tools have rendered stocks and logistics hubs more vulnerable. Disguise and camouflage technologies have also evolved. All these factors need to be considered in the context of multi-domain operations. New concepts such as ‘distributed sustainment operations’ have emerged, and seem better suited to today’s battlefield challenges.

Strengthening our Economies

Ensuring the aforementioned “bridge between deployed forces and the industrial base” means a logical continuity between production logistics, in-service and operational logistics, in the framework of short-, medium- and long- term capability planning, which reflects the doctrine, military and industrial requirements of a nation, or of a group of nations.

The particularity and challenge of the Ukrainian experience is that several elements of ‘logical continuity’ are discontinued and scattered. That is, in this author’s view, because, at the beginning of the Russian invasion, the conflict was hoped to be a short one.

Unlike other conflicts where western countries were called upon to provide support using pre-established capability planning, the war in Ukraine has forced rapid adaptation of capability planning including at the production logistics level. It may even trigger a whole rethink of our industrial strategies with repercussions that go beyond the defence sector. The widely-debated ammunition shortage issue could also raise the question of whether post-Cold War capability planning was thorough enough in envisaging possible scenarios which could arise.

Credit: US Army/Staff Sgt. Gabriel Rivera-Villan

The Ukraine war also had several ‘side-effects’ which will likely impact how we think of logistics beyond the military. Firstly, the conflict has triggered an unprecedented level of unity at the European level, which has facilitated rapid decision-making on the reinforcement of European defence. Under different circumstances, it would have probably taken much longer. The EU Commission’s plan to boost European defence production capacity via the European Defense Industry Reinforcement Through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) illustrates this.

The war was also a bitter realisation that we need to invest more in our industrial production capacity and better secure our supply chains. The war has heavily disrupted the latter, in nearly all economic areas, and added to existing challenges that became apparent during the COVID pandemic. As such, the countries of the trans-Atlantic space need to rethink their industrial strategies, as well as coordinate and to re-prioritise where necessary.

Conclusions

The Ukrainian experience so far has been a lesson in modern warfare, which has prompted the adaptation of logistics doctrines to its realities. It forced Ukraine and its Western allies to seek innovative solutions to assure continuity between operational, in-service and production logistics in new scenarios, and in new ways. It also demonstrated that shared values and objectives can help overcome many practical logistic problems, and served as a reminder of the importance of nearly forgotten concepts, such as stockpiling. It also reminded us that, besides equipment, the most important asset – including in logistics – is people, their training and their education, and that this is not only the responsibility of the military but of our education systems as a whole. This should incentivise thinking about and taking steps to strengthen our industries and boost our economies over the long term. Lastly, the conflict has demonstrated that coordination and cooperation can work, as well as the benefits of unity.

Manuela Tudosia