With the re-election of US President Donald Trump, questions regarding the transatlantic relationship between the US and Europe have once again come to the forefront, including the extent to which the US needs Europe.

A sober reading shows that the US has good reason to remain engaged in Europe; most notably, US security depends on various military facilities in Europe to provide detection, tracking and interception capabilities for its ballistic missile defence.

The Continental United States (CONUS) faces potential ballistic missile threats from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation. Elsewhere, other US interests face ballistic missile threats from the Islamic Republic of Iran, as noted in a Stratfor analysis summarising the estimated maximum ranges of Iran’s ballistic missiles. The analysis noted that Iran’s Khorramshahr-4 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) has a possible range of almost 2,000 km. While insufficient to hit CONUS targets, such a missile could still threaten US interests in the Middle East, with US ally Israel well within range.

The American Security Project, a Washington DC-based think tank, assert that the US deploys forces to approximately 30 bases spread across Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. All these bases are at potential risk from attack by weapons such as the Khorramshahr-4, as well as other types of ballistic missile possessed by the DPRK, PRC, and Russia. For example, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), another Washington DC think tank, estimates the DPRK’s KN-22 Hwasong-15 to have a range of 13,000 km. CSIS assesses the PRC’s DF-5 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) having a similar range. Russia’s RS-28 Sarmat (NATO reporting name SS-X-29/30) has a range of 10,000-18,000 km, CSIS estimates.

A general rule-of-thumb states that ICBM flight trajectories follow the so-called Great Circle Route which exploits the shortest distance between two points on Earth. It would take another article to explain the trigonometry of the Great Circle Route but to understand how the route works, consider this example. Russia has an ICBM base at Yoshkar-Ola in the West of the country. According to the March 2022 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Nuclear Notebook, this facility is home to the 14th Missile Division. The division comprises the 290th, 697th and 779th Missile Regiments. Each regiment has nine MZKT-79221 heavy trucks capable of deploying and launching RT-2PM2 Topol-M (NATO reporting name: SS-27 Sickle-B) ICBMs. Open sources state these missiles have a range of 11,000 km and travel at a top speed of 27,100 km/h.

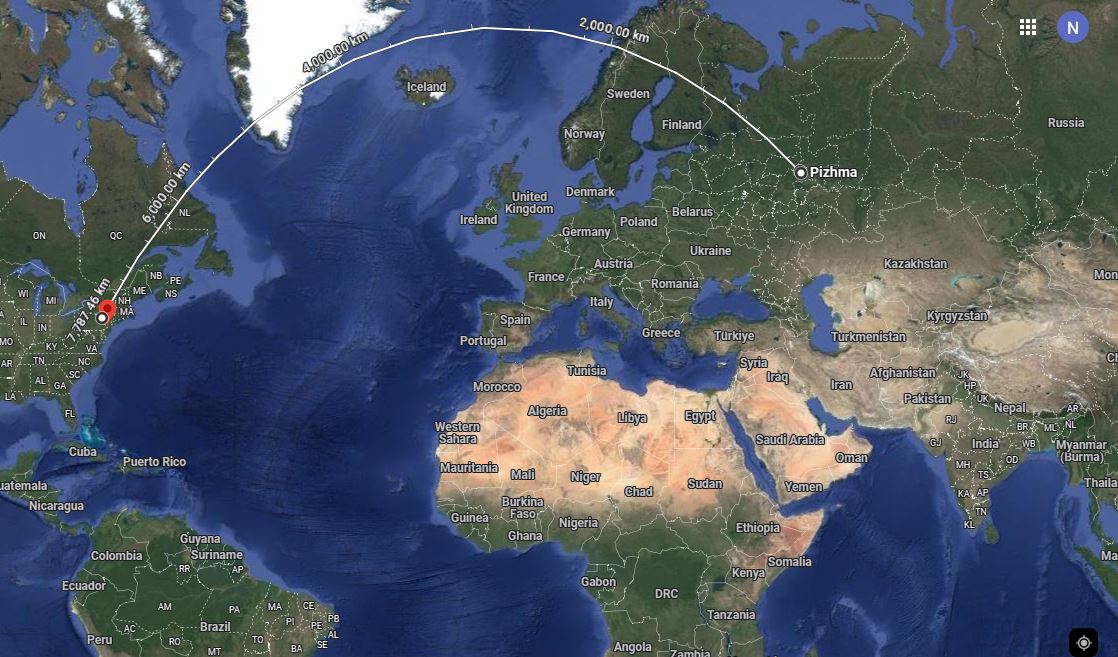

A Russian Strategic Rocket Force RT-2PM2 Topol-M ICBM on its 15U175 transporter erector launcher (TEL). Being based on a mobile wheeled platform allows Russia to launch these missiles from remote locations, making the precise launch location difficult to predict. [RecoMonkey]Suppose that the US and Russia were on the brink of nuclear war. The 14th Missile Division’s regiments would be deployed into the Russian countryside from their base. This is a standard tactic to reduce the chances of the division being destroyed should a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the facilities in Yoshkar-Ola occur. Deploying the regiments in this way keeps the trucks mobile, making them easier to camouflage and harder to locate. Once the trucks have launched their missiles, they can relocate to a safe area to reduce the chances of being destroyed in a retaliatory attack. Let’s assume that one SS-27 launcher has deployed to Pizhma, around 141 km north-northwest of Yoshkar-Ola. The missile’s target is McGuire airbase, New Jersey.

The ICBM must travel 7,844 km to reach its target. The Topol-M is thought to carry a single 800 kt warhead, equivalent to 800,000 tonnes of TNT. The aimpoint is between the base’s north-south runway 18/36 and northeast-southwest runway 06/24. The missile is fuzed for a surface burst with the intention of causing maximum destruction at the base. According to a simulation performed using the nuclearsecrecy.com website, the detonation would immediately kill approximately 10,640 people and injure 14,530. The resulting fireball would have a radius of almost 1.3 km. Anyone within a 9.7 km radius of the fireball would suffer third-degree burns and those within 2.4 km of ground zero, who had survived the initial attack, are likely to perish through acute radiation sickness within one month. Radioactive fallout could drift as far as Boston, around 388 km (241 miles) northeast of ground zero.

Initial detection of the incoming missile would be made by the US Space Force’s SBIRS (Space-Based Infrared System), which is a constellation of satellites designed to detect the hot exhaust plume of a ballistic missile as it heads into space. Once the constellation has detected the Topol-M’s plume, the target would need to be confirmed by radar. The Royal Air Force (RAF) has a Raytheon AN/FPS-132 ultra-high frequency (UHF) 420-450 MHz ballistic missile detection and tracking radar with a published range of 4,800 km and is located on Fylingdales Moor in north-east England. According to the RAF’s website, the AN/FPS-132 at Fylingdales provides “a continuous ballistic missile early warning service to the United Kingdom and US Governments ensuring a surprise missile attack cannot succeed”. RAF Fylingdales shares its radar picture with the US-Canadian North American Air Defence Command (NORAD), which protects Canada and the CONUS against air and ballistic missile attack.

The AN/FPS-132 is likely to be one of the first radars to see the Topol-M as it appears above the horizon on its way into space. Next, a US Space Force AN/FPS-132 based at Thule, western Greenland, will provide additional confirmation on the ICBM some minutes later. NORAD is then likely to activate the US Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) infrastructure in an attempt to engage and destroy the Topol-M before it reaches McGuire. With a flight time of around 20 minutes, every second counts.

American kinetic BMD assets include US Navy Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers, equipped with Lockheed Martin’s Aegis BMD variant of the well-known Combat Management System (CMS). These ships possess one surface-to-air missile (SAM) type which could notionally intercept the Topol-M during the midcourse phase: Raytheon’s RIM-161D Standard Missile-3 Block IIA (SM-3 Blk IIA); though it should be noted that the manufacturer only announced that the missile had entered full-rate production on 15 October 2024, and as such it is likely that most vessels lack the SM-3 Blk IIA in their loadout for the time being. The missile uses infrared (IR) homing for terminal guidance, supplemented by a combined global positioning system (GPS) and inertial navigation system for the flyout.

Europe is also advancing its missile defence capabilities as evidenced in October 2024, when the first successful launch of Eurosam’s Aster-30B1NT SAM was reported to have taken place in France. The reports continued that the Aster-30B1NT can engage ballistic missiles with ranges of up to 1,500 km – this category would include short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) and some medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs). Furthermore, the missile’s Ka-band (33.4-36 GHz) radar seeker can is reported to be capable of differentiating between ballistic missile warheads and decoys. Aster-30B1NT SAMs will equip the Horizon class destroyers of the French and Italian navies, and the Royal Navy’s Type-45/Daring class destroyers. French and Italian Eurosam SAMP/T NG long-range, high-altitude SAM batteries will also receive this new missile.

Aegis Ashore

Upon receiving confirmation that the Topol-M is incoming, US decision-makers have another option to intercept the missile beyond naval vessels. The Aegis BMD CMS forms the basis for the command and control system for the US Aegis Ashore facilities in Europe. Much like the aforementioned US Navy warships, Aegis Ashore uses Lockheed Martin’s AN/SPY-1 series S-band (2.3-2.5 GHz/2.7-3.7 GHz) naval surveillance radars to detect and track ballistic missiles as they appear above the horizon, and is armed with SM-3 series SAMs for interception. Two Aegis Ashore facilities are based in Europe, the first located in Deveselu, southern Romania, which was declared operational in May 2016.

The second is located at Redzikowo airbase in northern Poland, which was declared active in June 2024. The elements of the US BMD system are networked using secure fibre optics, conventional telecommunications and satellite communications. In a hypothetical scenario such as the aforementioned Topol-M attack, it is possible that the Aegis Ashore facility in Redzikowo would be among the first assets to detect the launch, and could be used for an initial attempt to intercept the Topol-M. Should this prove unsuccessful, BMD-capable naval assets could be used downrange for additional attempts.

Weighing the benefit

As outlined, US ballistic missile defence benefits heavily from facilities in Poland, Romania, Spain, Türkiye, and the United Kingdom. All these bases play a vital role in providing the early detection of ballistic missile threats, including those heading toward targets in CONUS, and provide an early opportunity to deal with such threats kinetically. Remove any one of these elements, and the BMD protection of the eastern US will be degraded.

The European-US defence relationship came under scrutiny during the previous Trump administration between 2017 and 2021. related to what President Trump saw as an imbalance between US spending on defence, compared to that of other Alliance members.

Trump arguably had a point, because at the time only a few NATO members met the non-binding requirement to spend a minimum of 2% of their GDP annually on defence. According to NATO’s own figures, as of 2024, 23 of the Alliance’s 32 members now meet or exceed this figure. This is a step in the right direction and it would not be surprising if further increases occurred in the future. Regardless of the path of the war in Ukraine, the threat posed to NATO by Russian revanchism is not dissipating. As a result, defence budgets across Europe show little sign of reducing.

However, the hard work of several European nations to meet these GDP targets appears to have done little to assuage Trump’s anger. In February 2024, he revealed that during his first term he had argued with an unnamed NATO ally, adding that he told that head of government he would encourage Russia “to do whatever the hell they want” to “delinquent” Alliance members not spending their dues. Arguably, his comments undermined NATO’s collective security pledge enshrined in Article 5 of the 1949 Atlantic Treaty, which stipulates that “if (an ally) is the victim of an armed attack, each and every other member of the Alliance will consider this act of violence as an armed attack against all members and will take the actions it deems necessary to assist the Ally attacked.” Article 5 was famously declared by NATO in the wake of the 11 September 2001 Al Qaeda attacks against New York and Washington. European NATO Allies later deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq in support of subsequent counter-insurgency campaigns there. A total of 1,145 Allied troops would lose their lives fighting in Afghanistan alone.

The danger is that any threat to leave the Alliance or actual withdrawal by the US could have a profound effect on US security, notably in the ballistic missile defence realm. What happens if the Trump Administration had a major disagreement with some Alliance members, or the Alliance as a whole? Would countries hosting key elements of the US BMD infrastructure ask for those facilities to be removed, or refuse permission for them to be used in times of crisis? This is no idle threat. In 1967, French President Gaulle took his country’s military out of NATO’s integrated military structure and also demanded that NATO and US units on French soil leave the country.

Although not a NATO operation, the governments of France and Germany refused to deploy troops to Iraq in 2003 to help the US oust Iraq’s dictator Saddam Hussein. Likewise, the UK refused to deploy forces to aid the US in the Vietnam War between 1965 and 1975. Trump may have said he would encourage Russian aggression against those not paying their dues in a fit of pique, but his administration should be cautious that any weakening of the Alliance by the US, could trigger a response in kind from Europe’s NATO members. In such a situation, the loser would not just be Europe, but potentially the US’ fundamental ability to protect itself.

Thomas Withington