Russia is violating hydrocarbon sanctions introduced because of Moscow’s continued occupation of Ukraine. A new initiative by the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force may help to combat Russia’s illicit oil exports.

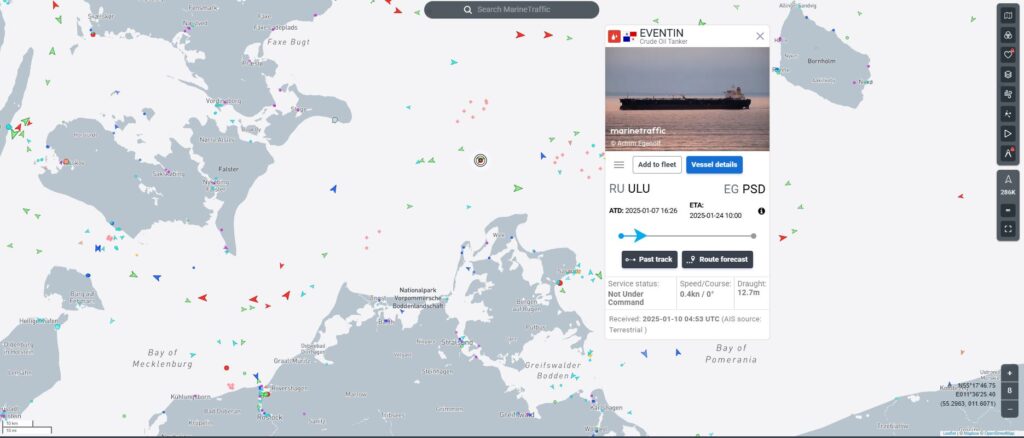

It was easy enough to see that the MV Eventin was not doing much in the Baltic Sea on the marinetraffic.com vessel tracking website. As of 11 January 2025, the Panamanian-flagged oil tanker appeared to have lost all power and steering, stuck in Germany’s territorial waters. Tugboats had reached the scene and secured the stationary ship. However, the MV Eventin was not perhaps all she seemed. Consider her voyage: According to marinetraffic.com she left the Russian port of Ust-Luga, on the Baltic coast close to the Russo-Estonian border on 7 January 2025.

The website revealed that she was heading to Port Said on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, at the mouth of the Suez Canal. At the time of writing, she had been detained by German authorities, reportedly due to her drifting off course and being unable to manoeuvre, and towed to Sassnitz on Germany’s Baltic coast, where she has remained since, along with her cargo comprising 99,000 tonnes of crude oil.

Shadow fleet

Russia is working hard to outflank the EU and G7’s hydrocarbon export sanctions. Part of Moscow’s approach has been to establish a shadow fleet of ships which “(make) use of flags of convenience and intricate ownership and management structures while employing a variety of tactics to conceal the origins of (the ships’) cargo”, according to a briefing on this subject written for the European Parliament. Sanctions covering the Russian oil sector prevents G7 members from “providing shipping, brokering, technical assistance or insurance services to facilitate the trade of Russian crude oil and petroleum products across the globe, unless the trade is verifiably below the price cap”, the briefing continued.

The issue for Moscow is that the price cap is supposed to prevent Russia from benefiting from fluctuations in the global oil price. Should the price fall below USD 60 per barrel, Russia will make a profit, but her oil will be comparatively more expensive. On the other hand, Russia cannot benefit from typical increases in the global price of oil. The statista.com website noted that the average per-barrel price for Brent Crude, the international standard benchmark, was USD 80.53 in 2024. Moscow was thus selling oil at a loss last year. The European Parliament briefing noted that G7 members dominate the global market for shipping services and maritime insurance. For example, Lloyds of London remains the world’s leading marketplace for marine insurance. G7 member companies are prevented by sanctions from providing Russian oil exporters these services and insurance.

Russian exporters are thus forced to look beyond G7 member nations for shipping services and marine insurance. One approach taken by the exporters is to charter vessels from so-called ‘flag of convenience’ states such as Panama. Ships registered to these states may benefit from a relatively lax enforcement of vessel safety or environmental regulations, the European Parliament briefing says. Vessels may not maintain adequate insurance, may avoid inspections, and may have poor crew safety and welfare standards. Shadow fleet ships may also have highly opaque ownership and management structures. Just as billionaires undertake efforts to conceal the location of their wealth to avoid tax, so ship owners can hide behind front companies.

The problem with Russia’s shadow fleet is that its ships may be unsuitable for hydrocarbon export. Vessels may be kept in an inadequate state of maintenance meaning they might be unseaworthy. This raises the danger that tankers could suffer mechanical problems, which may have been the case for the MV Eventin. Crews may also have inadequate levels of training, and working conditions may be unconducive to personnel working in a safe and responsible manner. These factors could cause shadow fleet ships to experience difficulties or even court disaster. A badly-maintained and crewed vessel is more likely to sustain damage that could risk the release of large volumes of oil into the sea. Opaque vessel ownership structures, and inadequate insurance, could make it difficult, if not impossible, to determine who is responsible. This could hamper efforts to hold people or organisations criminally or financially liable.

Chasing shadows

Fortunately, it is becoming increasingly difficult for merchant vessels to hide nefarious activities. G7 members are deepening their abilities to keep tabs on what ships are doing on the high seas. All vessels need to carry radars for navigation and radio communications. Merchant shipping uses very high frequencies (VHF) of 156-157 MHz, and 156-162 MHz, reserved by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) for radio communications. The ITU is the UN body which globally regulates the radio spectrum. The ITU also makes several ultra-high frequency (UHF) wavebands from 457.525-467.825 MHz available for marine radio communications. Ships can use high-frequency (HF) radio across frequencies of 4-8.815 MHz. Medium-frequency communications on wavebands of 405 kHz to 2.850 MHz supplement HF. Satellite communication (SATCOM) is used extensively by merchant shipping. A myriad of service providers including Thuraya, Iridium and Inmarsat use SATCOM frequencies spanning from 1.525-1.646 GHz. Ships need navigation radar which typically transmit radio signals in S-band (2.3-2.5 GHz/2.7-3.7 GHz) and X-band (8.5-10.68 GHz).

All these radio emissions from a merchant ship can be detected with an Electronic Support Measure (ESM). The ESM could be located at a coastguard station, equip a vessel or maritime surveillance aircraft or even be onboard a satellite in space. The system will detect radar communications, radar and AIS transmissions, provided the vessel is in a line-of-sight range from the receiver. At the very least, the ESM will detect a bearing from itself to the source of the transmission. Find the source of the transmission and you find the vessel. The ESM may be able to triangulate the source of the transmissions, giving even more detailed information on the ship’s location. The first indication that a vessel maybe acting suspiciously is that its AIS maybe switched off or transmitting false information. It may make sense to restrict AIS transmissions transiting through the Gulf of Aden, a piracy hotspot, but inactive or inaccurate AIS data may seem more suspicious in the relatively peaceful Baltic. For example, a vessel’s AIS may indicate that she is underway off the coast of Chile, carrying a cargo of timber bound for the Chilean port of Concepción. Yet closer inspection by a maritime surveillance aircraft may reveal the ship is in fact in international waters close to Rostok on Germany’s Baltic coast, and resembles an oil tanker.

Baltic monitoring

Given Russia’s desire to flout oil sanctions using potentially unsafe vessels in European waters, the UK Government announced in January 2025 it was activating the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) Reaction System. According to the government, the JEF is “a pool of high readiness, adaptable forces … designed to enhance the UK’s ability to respond rapidly, anywhere in the world, with like-minded allies, or on behalf of international organisations such as the UN or NATO.” The UK leads the JEF, which includes Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. The JEF’s primary goal is “protecting northern Europe”. The new reaction system is to “track potential threats to undersea infrastructure and monitor the Russian shadow fleet”.

The Baltic Sea has witnessed multiple instances of critical underwater infrastructure (CUI), such as undersea cables, being damaged, likely deliberately by ships which may form part of the shadow fleet. For instance, on 25 December 2024, the Estlink-2 electricity cable linking Finland to Estonia suffered a power outage. The incident occurred shortly after the MV Eagle S oil tanker had crossed over the cable. The ship was travelling from Ust-Luga in Russia, carrying petroleum, possibly either to Türkiye or Egypt. The Finnish authorities impounded the ship and crew which, as of mid-January 2025, remain in the Finnish port of Porvoo Anch. The MV Eagle S is reportedly registered in the Cook Islands, a flag of convenience state, and is operated by a company registered in the UAE.

The JEF Reaction System will not stop the activities of Russia’s shadow fleet by itself, but it will help to ensure that G7 members can continue to apply pressure to Moscow’s illicit oil exports. Data from the system may also prove useful in future legal action concerning shadow fleet activities. It is reassuring that, despite the damage it may have caused, the MV Eagle S is languishing in a Finnish port. Finnish law enforcement is reportedly investigating the crew. Meanwhile, the MV Eventin seems unlikely to complete her voyage anytime soon. In the long game of combating Russian oil sanctions evasion, initiatives like the JEF Reaction System will prove invaluable.

Thomas Withington