North Korea tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) on 18 February 2023 that, according to North Korean news agency KCNA, was a Hwasong-15 ICBM. The missile was fired at a high angle and reached a maximum altitude of about 5,770 km. Its 67-minute flight ended 990 km from its launch site in the sea area between the Korean peninsula and Japan.

This test with an ICBM was followed by the launch of two short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) on 20 February. According to KCNA, these were intended to simulate engagements with targets at a distance of up to 395 km. The missiles reached a maximum altitude of between 50 and 100 km, according to Japanese and South Korean analysis.

However, on 18 November 2022 North Korea had successfully tested a newer ICBM: the Hwasong-17. According to Japanese reports, the impact from this test was recorded about 210 km west of the Japanese island of Oshima in the Sea of Japan (about 300 km west of Fukushima). According to KCNA, the missile travelled 999.2 km and reached a maximum altitude (apogee) of 6,040.9 km. The launch time was 10.15 am local time and the flight duration was given as “4,135 seconds”. The information about the launch site, however – “launched at the Pyongyang International Airport” – does not match the published pictures: an inconsistency that surely occurred for reasons of secrecy. During its 69-minute flight, the Hwasong-17 is said to have reached 22 times the speed of sound. The latter is based on information from Seoul, going back to analyses by the intelligence services in South Korea and the United States.

ICBM tests as strategic communication

The North Korean ICBM test on 18 February 2023 can be deemed to be associated with trilateral military exercises between the United States, Japan and South Korea, which began just days after the North Korean missile launches; Pyongyang had previously threatened “further strong steps” because of the manoeuvres.

Beyond the signal to its immediate neighbourhood, North Korea’s missile tests can also be understood as a message to countries further afield. In November 2022 the heads of state and government of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) met for a summit in Bangkok, while the 27th UN Climate Change Conference took place in Sharm El Sheikh from 6 to 18 November 2022 and the 17th G20 leaders’ meeting, featuring a summit between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden, ended on 16 November 2022, by which time preparations for the 18 November Hwasong-17 test were already underway.

Pyongyang regards the military presence of the United States in South Korea and Japan as a hostile act. The White House’s behaviour seems encroaching to the regime anyway and thus, in Pyongyang’s eyes, justifies its weapon tests as a reaction to the United States’ “provocative military exercises” in the region. Its own military exercises and the missile tests are declared to be an expression of North Korea’s legitimate reaction to the existential threat it claims to face. In this respect nuclear deterrence is an indispensable element of the regime’s security policy. Quoting from a KCNA communiqué of 19 November 2022: “This was done within the framework of the strict implementation of the strategy of the Workers’ Party of Korea and the North Korean government, which is to constantly strengthen the strongest and most absolute nuclear deterrent.”

For North Korean leader Kim Jong-un there may be the added perception that nuclear deterrence is the only way he can hold his own against external threats, with the fates of the Iraqi and Libyan dictators Saddam Hussein and Muammar al-Gaddafi perhaps providing a particular lesson.

Reactions from the international community to North Korea’s missile tests follow a familiar template. Condemnations by the G7 and the EU immediately followed the launch on 18 February. On 19 February the German government called on North Korea “to fully implement the resolutions of the Security Council and to respond to the offers of the USA and South Korea to enter into a serious dialogue”.

The UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions prohibit North Korea from developing means of transporting conventional and nuclear explosive devices and nuclear weapons. They also explicitly prohibit “all ballistic missile tests” by North Korea.

To be sure, there are repeated signs that patience with North Korea may be running out, but the regime also finds backing. In May 2022 Russia and China vetoed a UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution introduced by the US to tighten sanctions against North Korea over its weapons tests. In this respect further measures by the UNSC against North Korea are rather unlikely, especially against the background of the current geopolitical situation.

Hwasong-17: a threat to Europe

In Southeast Asia the new threat emanating from the Hwasong-17 test was quickly laid out. US media quoted Japanese Defence Minister Yasukazu Hamada as saying that the missile had a range of more than 15,000 km. A South Korean expert said he believes the Hwasong-17 could carry three to five nuclear warheads and reach a range of up to 15,000 km. The regime first unveiled the Hwasong-17 ICBM at a military parade in October 2020.

The two previously tested Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15s have a range of about 8,000 km. With these Pyongyang was already able to threaten Hawaii, Alaska and the US Pacific coast. The Hwasong-17, however, could threaten the entire mainland of the United States.

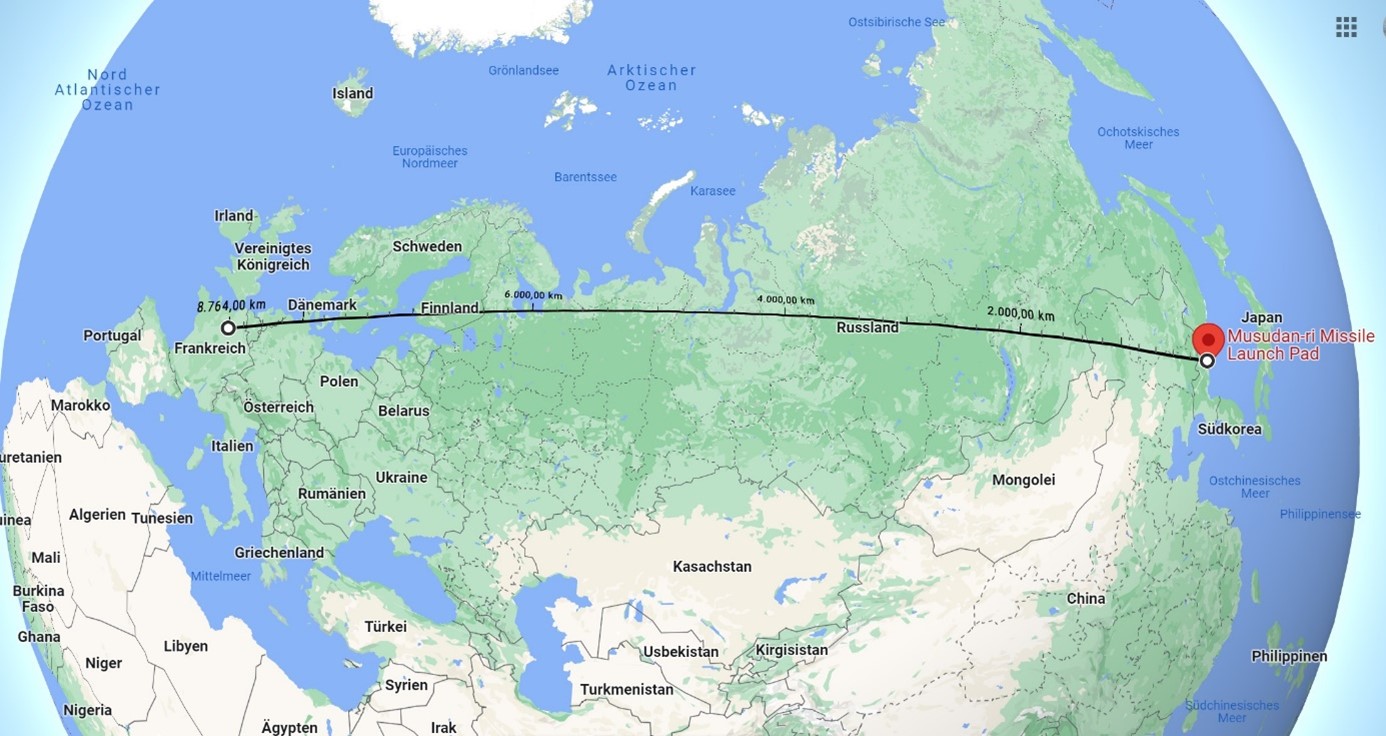

When Pyongyang conducted such tests in the past, the European public usually reacted with a shrug, but with the Hwasong-17 comes a new threat, given that targets in Europe are within its range. If the dichotomous treatment of China already neglected the nuclear threat, Pyongyang’s new achievement presents some startling facts. Paris, for example, is 8,760 km away from North Korean launching positions.

Nuclear specialists estimate that North Korea has fissile material for 20 to 60 nuclear warheads. According to the US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the country has reached the level of miniaturisation to assemble nuclear warheads for both SRBMs and ICBMs.

In view of these analyses, it becomes almost imperative that Europeans become aware of these risks, forcing the EU to adopt a truly global perspective and consider the long-range threats appearing on its radar.

Hans-Uwe Mergener