This article looks briefly at some of the threats to world peace from nuclear weapons in today’s geopolitically explosive world. These threats have brought us to the edge of a very dangerous abyss. It also touches upon nuclear deterrence as the option favoured by Western powers and the Alliance, bolstered by strength and nuclear options that include US strategic forces and land-based missile systems.

If an aggressor decides to use a nuclear weapon in the context of today’s global geopolitical tensions, the result will not be good for any life form on this planet. There will be no winners and, undoubtedly, a nuclear response will follow, an option that did not exist before when in WW2, the world’s eyes were opened to the horrors of what unleashing a nuclear ‘option’ on the battlefield looked like, with Hiroshima and Nagasaki suffering the effects of what, today, would be seen as tactical yields. The Japanese possessed no atomic bomb with which they could respond and so the Americans had no fear when they dropped ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ on their respective targets.

Since those horrors in 1945, and despite other lesser conflicts, Cold War tensions, and more – including the Cuban Missile Crisis – there has been a relative period of peace from large-scale confrontation, with a largely rules-based approach followed by all powers sharing the planet. One could almost be forgiven for thinking that two world wars had taught enough lessons to last an eternity.

The Nuclear Spectre over Ukraine

Yet a rules-based world no longer seems to prevail. Nuclear weapons are now being waved around in threat displays on the battlefields of Ukraine by Vladimir Putin, and in regular shows of technological capability though overt aggressiveness by North Korea. Indeed, Putin is obviously willing to flaunt international conventions as has been displayed with attacks on civilians and civil infrastructure, and his disregard for causing mass destruction wrought from the breaching of the Kakhovka Dam in southern Ukraine. This caused extensive flooding along the lower Dnipro River and suggests he may be more than willing to escalate further. At the time, Ukrainian President Zelensky called it ‘an environmental bomb of mass destruction’ and the country’s prosecutor general’s office called it a possible crime of ‘ecocide’. However it is seen, Putin’s nuclear sabre rattling since last February’s invasion of Ukraine has been a mainstay of the Kremlin’s playbook to keep Ukraine and the West afraid and guessing.

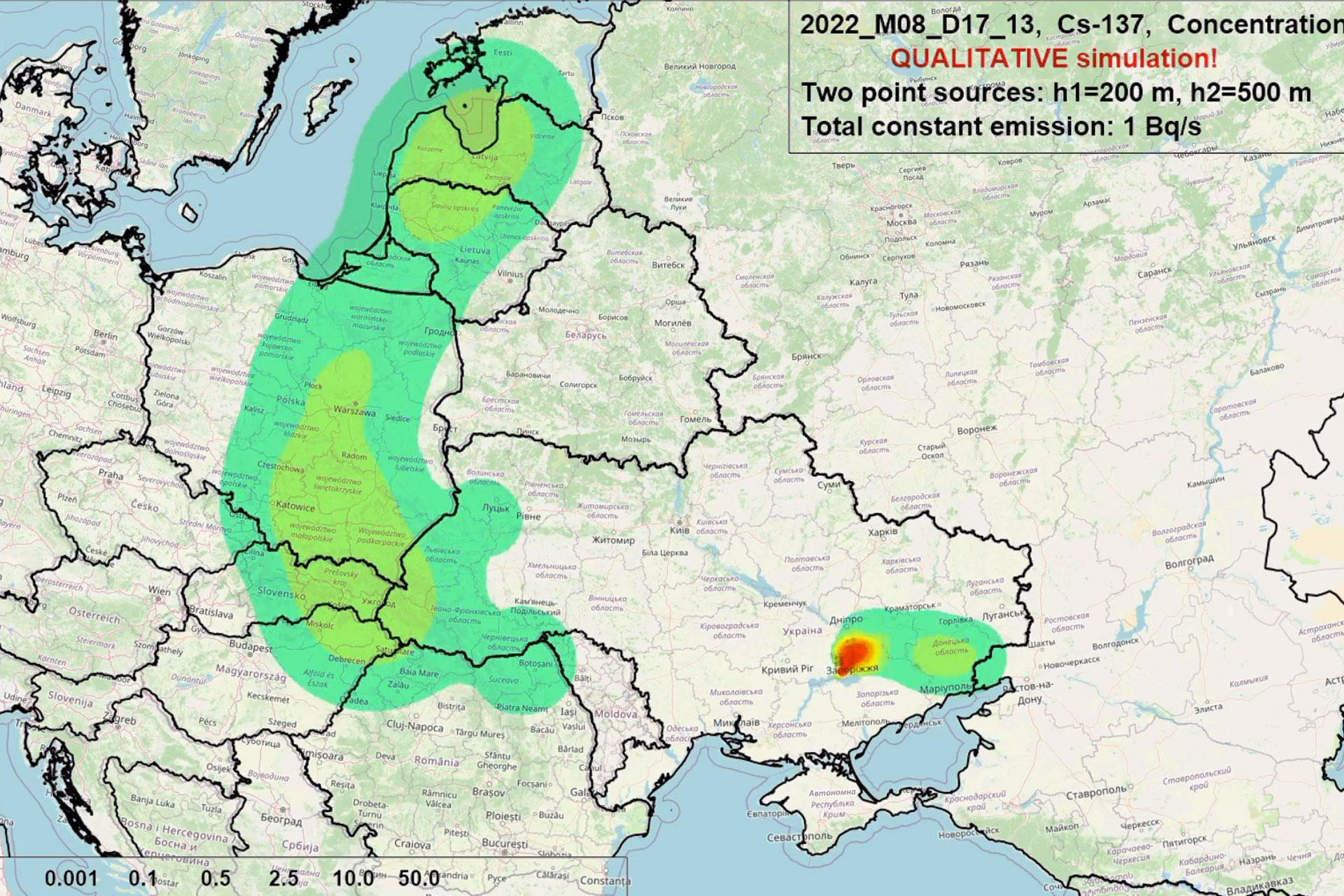

By way of example, Ukrainian intelligence claimed in late June 2023, that Russian leadership may even instigate a nuclear incident around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Were that to happen, how the West would respond is uncomfortably uncertain, for damage or destruction of the power plant could result in radiological contamination across a wide European geographical landscape.

Would such an act warrant a NATO response of any kind, since Alliance nations would certainly be affected by the fallout? In 2022, the Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Institute simulated what a disaster at Zaporizhzhia might look like, with a radioactive cloud modelled to disperse over 13 countries, including the three Baltic States, Belarus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Russia and, of course, Ukraine. Considering contamination after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster was carried as far as Norway, Sweden and north Wales, this list may be conservative.

Russia’s nuclear options also include tactical nuclear weapons stationed on Belarusian soil, which was begun in May 2023 and by mid-June Putin announced the first batch had been moved. President Lukashenko used language suggesting a willingness to use them, when he compared them to the weaponry supplied to Ukraine by NATO nations, stating: “they’re all just weapons”. While the US has been critical of the nuclear deployment, it has stated no intention of altering its own posture on strategic nuclear weapons, nor has it seen any signs that Russia might be preparing to use a nuclear weapon.

That said, the Russians have not revealed which tactical nuclear warheads have been deployed, although Lukashenko has said they are three times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in August 1945. Putting that in perspective, the enriched uranium-235 ‘Little Boy’ dropped on Hiroshima was about 15 kilotons, equivalent to 13,600 tonnes (15,000 US tons) of TNT, while the plutonium-239-based ‘Fat Man’ bomb dropped on Nagasaki was about 21 kilotons. Sobering, considering Lukashenko cautioned in the same breath that any aggression against Belarus would result in an instant response, with targets already defined.

That the same forces who blew up the Kakhovka Dam possess tactical nuclear weapons, and are currently in a defensive posture, combined with the fact that the US has upped the weapon-supply ante with deliveries of cluster munitions to Ukraine, has caused concern that tactical nuclear weapons will be used if the counteroffensive looks like succeeding.

The likelihood that they will be used is thought to be even greater should Russian forces look like they are being routed, and especially, if Crimea, including the naval base in Sevastopol, comes under serious threat. Basically, if Russia looks like losing, Putin, may simply give the order to use tactical nuclear weapons – either from Russian or Belarusian territory, to force Ukraine into submission. One last, desperate attempt to take control and save himself while possibly obliterating major cities and civil infrastructure.

Threats from Elsewhere

Beyond the immediacy of the nuclear threat from Russia in Ukraine, as already mentioned, North Korea keeps nuclear tensions high on the Korean Peninsula and beyond with its repeated test launches of ballistic missiles into the East Sea, also known as the Sea of Japan, and nuclear developments showcased for all the world to see. What option does the West have in this regard? Diplomacy to try and get the regime to end its nuclear programme has failed miserably.

Indeed, in 2018, Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, said that North Korea was the greatest threat to global peace at that time and that, “the essence of the matter: North Korea acquired nuclear weapons to assure its regime’s survival; in its view, to give them up would be tantamount to suicide.” Chillingly, around the same time, he also posited that the world was almost at the point, or may soon reach it, when taking the option of a pre-emptive strike was the only remaining way to deal with North Korea, since diplomacy, Chinese co-operation and all other means had failed – although no administration members have ever suggested anything similar. Certainly, this geopolitical cauldron cannot be ignored.

Then there’s Iran, not yet a nuclear power, but allegedly heading in that direction. In early June 2023, the country’s Islamic Republic News Agency reported the unveiling of a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) named Fattah. Interestingly, the missile appeared to use a manoeuvrable re-entry vehicle (MaRV) design, featuring a manoeuvring second stage with aerodynamic control surfaces, and appearing to be paired with a rocket motor with a thrust vector control (TVC) capability. These features would respectively allow it to manoeuvre in both endo-atmospheric and exo-atmospheric conditions, significantly complicating the task of intercepting it.

In terms of official statements regarding its capabilities, Revolutionary Guards Corps head, Amirali Hajizadeh, was quoted by Iranian state media as saying that, “The precision-guided Fattah hypersonic missile has a range of 1,400 km and it is capable of penetrating all defence shields.” State television said the missile the missile’s top speed could reach Mach 14 (15,000 km/h), which is not particularly surprising for a ballistic missile.

While Iran has consistently denied any ambition to obtain a nuclear bomb, its resumption of nuclear-oriented activities since 2018, after the US withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal between six leading nations has reignited fears that producing a nuclear bomb remains its ambition. Whether Israel would stand by and watch that happen is unlikely.

No analysis on the threat to world peace from nuclear weapons would be complete without mention of China. Its ’Belt and Road’ initiative since 2013 has given Beijing a footprint, a foothold even, the world over, through a global infrastructure development strategy to invest in more than 150 countries and international organisations. Yet, its militarisation of the South China Sea and bellicose statements in the direction of Taiwan have been a cause for significant concern in the West.

Kissinger said recently that he believed US-China tensions are imitating those of the Cold War era. This time, however, with the possibility for destruction having increased drastically, including the likelihood that the US and its allies will be at war with China by 2030. If that is so, the potential for nuclear exchange, both at tactical and strategic levels, is significant.

However, rather than continuing along such alarming lines the article will continue with a look at US and NATO ally fundamentals of nuclear deterrence, along with other reassuring developments.

The Option of Deterrence – a Political Choice

In its 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), the US Department of Defense (DoD) outlined the ‘Declaratory Policy’ of the US: ‘As long as nuclear weapons exist, the fundamental role of US nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners. The US would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States, or its allies and partners.’

That said, the US has reduced the size of its land-based nuclear weapons stockpile by over 90% since the height of the Cold War, including the number of nuclear weapons stationed in Europe, which nonetheless remain a fundamental part of NATO’s nuclear calculations. Indeed, for NATO, US nuclear weapons are the mainstay of the Alliance’s nuclear arsenal. They are also a core component of its overall capability for deterrence and defence, alongside conventional and missile defence forces. As long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO makes clear that it will remain a nuclear alliance with a deterrent policy and a non-offensive nuclear capability intended to preserve peace, prevent coercion, and deter aggression.

Two documents set out NATO’s current nuclear policy which have been agreed by all Alliance members; one is ‘The 2022 Strategic Concept’, and the other ‘The 2012 Deterrence and Defence Posture Review (DDPR)’. In the concept document agreed at the 2022 Madrid Summit, deterrence and defence are stipulated as core tasks and principles of the Alliance based on an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities, complemented by space and cyber capabilities, with Article 30 of the Strategic Concept stressing that, “NATO will take all necessary steps to ensure the credibility, effectiveness, safety and security of the nuclear deterrent mission.

The Alliance is committed to ensuring greater integration and coherence of capabilities and activities across all domains and the spectrum of conflict, while reaffirming the unique and distinct role of nuclear deterrence. NATO will continue to maintain credible deterrence, strengthen its strategic communications, enhance the effectiveness of its exercises and reduce strategic risks.”

That said, for such deterrence to be effective, NATO makes clear that Alliance unity and resolve in such deterrence must be underpinned through the broadest possible participation by those allies concerned with agreed, nuclear burden-sharing arrangements. To this end, it was the 2012 DDPR that, while noting the fundamental purpose of Alliance nuclear forces is that of deterrence, also impressed that any decision to take a nuclear option is, essentially and definitively, a political one.

So, despite Alliance forces maintaining and being the custodians of its effective deterrence, nuclear weapons are under political control in all circumstances, with nuclear planning, consultation and actions within the Alliance conducted purely in accordance with strict political guidance.

To that end, the key principles of NATO’s nuclear policy are established by all NATO heads of state and government, with the development and implementation of Alliance nuclear policy the responsibility of its Nuclear Planning Group (NPG), which provides the forum for consultation on all issues that relate to NATO’s option of nuclear deterrence. With the exception of France, all members of the Alliance are in the NPG.

NATO’s Nuclear Options and Capabilities

While the circumstances under which NATO might have to use nuclear weapons are remote, their use by a belligerent against an Alliance member would fundamentally alter the nature of any conflict. In such a scenario, NATO states that it has the ‘option, capabilities and resolve to impose costs’ on an adversary that would be unacceptable and far outweigh the benefits that any such enemy force could hope to achieve by using nuclear weapons.

Indeed, NATO’s strategic forces, particularly those of the US, are the greatest guarantee of Alliance security, along with the independent strategic nuclear forces of the UK and France, which have deterrent roles in their own right, with separate decision-making centres.

France, the UK, and the US contribute to deterrence by also complicating the defensive/offensive calculations potential adversaries must make. Not only must they contend with NATO’s overall decision-making, but also the independent decision-making from political leaders in the US, the UK and France, should the adversary choose to attack an Alliance member and use nuclear weapons.

As stated above, NATO’s nuclear deterrence posture relies on forward-deployed US nuclear weapons in Europe, in addition to infrastructure provided by allies concerned, together with their own nuclear-relevant capabilities. Several NATO member countries contribute a dual-capable aircraft (DCA) capability to the Alliance, which are available for nuclear roles at various levels of readiness central to NATO’s nuclear-deterrence option, and for which they are equipped to carry nuclear bombs in a conflict. Such nuclear sharing plays a vital role in the cohesiveness of the Alliance and the indivisibility of security of the whole Euro-Atlantic area. That said, while the Allies provide military support for the DCA mission with conventional forces and capabilities, the US maintains absolute control and custody of its forward-deployed nuclear weapons.

America’s Approach and Nuclear Triad

On land, at sea and in the air, a compilation of platforms and weapons, the three legs of the US nuclear triad, serve as the backbone of America’s national security, as well as offering wider security to its allies and NATO member countries. This triad, along with assigned forces, provides 24/7 deterrence and stands ready to deliver a decisive response, anywhere, anytime. Indeed, the aforementioned 2022 NPR states that the US must be able to deter both large-scale and limited nuclear attacks from a range of adversaries. It also states that the capability to deter limited nuclear attacks is critical, given that some adversaries, “have developed strategies for warfare that may rely on the threat or actual employment of nuclear weapons in order to terminate a conflict on advantageous terms”.

The NPR adds: “given the US global alliance network is a military centre of gravity, the US will continue to field flexible nuclear capabilities and maintain country-specific approaches that reflect our best understanding of adversary decision making and perceptions”.

The US’ domestic nuclear forces include more than 10,000 people, who provide up to 400 on-alert, combat-ready LGM-30G Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), in hardened silos across five states and make up the most responsive leg of the nuclear triad. These strategic weapons are dispersed to protect against attack and connected to an underground launch control centre through a system of hardened cables.

This ICBM force has remained on continuous, round-the-clock alert since 1959, though is soon to be replaced by the USAF LGM-35A Sentinel weapon system, (formerly the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent programme), which will begin the replacement of Minuteman III and modernisation of the 450 ICBM launch facilities in 2029. The Sentinel is scheduled to attain an initial operational capability (IOC) in 2029, and full operational capability in the mid-2030s.

Following detailed environmental analysis, clearance to begin the construction phase of Sentinel was given in May 2023. The effort to modernise the land-based leg of the US nuclear triad affects multiple states, covers thousands of miles, and impacts communities in Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah and Wyoming.

While up for replacement, Minuteman III remains at total readiness. Indeed, in April 2023, a joint team of USAF Global Strike Command and USN personnel aboard the Airborne Launch Control System launched an unarmed Minuteman III ICBM equipped with one test re-entry vehicle from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. This was part of routine, periodic activities, with such tests having occurred over 300 times before. the US emphasised at the time that this recent test was not the result of current world events. A previous test launch had taken place in February.

The ICBM test launch programme demonstrates the operational capability of Minuteman III and ensures the US ability to maintain a strong, credible nuclear deterrent. Data collected from test launches is used for continuing force development evaluation. As for USAF Global Strike Command, this is a major command with headquarters at Barksdale AFB, Louisiana, which oversees the nation’s three intercontinental ballistic missile wings, the USAF’s entire bomber force, including: B-52, B-1 and B-2 wings, the Long-Range Strike Bomber programme, Air Force Nuclear Command, Control and Communications systems, and operational and maintenance support to organisations within the nuclear enterprise.

Approximately 33,700 personnel are assigned to two numbered air forces, with nine wings, two geographically separated squadrons, and one detachment, based in the continental US and deployed around the globe.

Sobering Thoughts

Back to Ukraine. Certainly, NATO, and the West in general, will have their respective nuclear doctrines, plans, options set out, but if the unfolding scenario between Russia and Ukraine does not go Putin’s way, this may lead us into the most dangerous period of the war so far. Having a response ready, were that to happen, is essential. We’ve already been tested: a critical infrastructure event causing mass destruction. A nuclear detonation could become the next big test.

Tim Guest