Following the announcement on 19 January 2024 that the UK’s DragonFire laser-directed energy weapon (LDEW) technology demonstrator had successfully conducted firing trials against aerial targets at a range in the Hebrides, the team behind DragonFire is now ready to develop it into one or more deployable weapon systems.

Senior officials from the DragonFire team, which brings together the UK Ministry of Defence’s (MoD’s) Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) with industry partners MBDA, Leonardo and QinetiQ, conducted a press briefing at Dstl’s Porton Down facility on 5 March to give an update on their progress and outline the path ahead.

Peter Cooper, Dstl’s principal LDEW advisor, told gathered journalists on 5 March that DragonFire represents a “step change in UK high-energy laser systems” and that the team was “now at the stage of understanding the art of the possible” regarding the system.

Richard Wray, MBDA UK’s director of engineering, conceded that, while some of the team’s presentation might look like science fiction, “it’s real now; the investment in technology in the programme that we have collectively been able to deliver has now given us that ability to offer this capability through to use”.

DragonFire uses a 50 kW-class laser to deliver its effect, but its required performance is said by the development team to be ‘equivalent to hitting a £1 coin from kilometres away’, all while the target is moving at speed –with the platform possibly also moving – and while delivering enough dwell time on the targeted point to deliver an effect.

Kenny McCormick, head of capability for advanced targeting at Leonardo UK, which is responsible for DragonFire’s beam director, noted that the pointing and tracking required is 10 times better than the pointing and tracking of a conventional weapon system, requiring techniques such as the development of a system that uses fast-moving mirrors to keep the beam on target.

McCormick also noted that Leonardo had had to develop an optical chain that would allow the beam director to cope with the high-energy laser beam that’s passed through it.

Mike Sewart, chief technology and operations officer for Qinetiq, additionally described some of the particular technologies unique to DragonFire. Firstly, he noted that the system uses a methodology of coherent combination, as opposed to the spectral combination technique typically used by other countries experimenting with laser weapons. With this technique the Dragonfire takes the power from its fibre amplifiers and splits it into coherent combinations, taking the power into an array of multiple beams and then coherently fusing those beams together to concentrate the power onto the target.

Secondly, Sewart outlined the DragonFire system’s beam-sharpening technology. This uses complex algorithms to address the atmospheric variations through which the beam passes, correcting it to ensure maximum effect on the target.

Further to its work on these novel technologies, Sewart said Qinetiq had also made extensive efforts to ensure the system architecture of the DragonFire demonstrator can be scaled – both up and down – according to what would be required in a deployable weapon system.

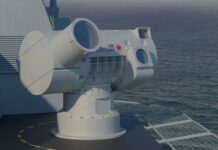

Asked by ESD what military application could potentially be first for a real-world system developed from the DragonFire demonstrator, Cooper replied, “Laser DEW has many applications and we are exploring all of them at present; we’re keeping it very open. But there are clearly some early winners. Air defence is well suited to the characteristics of the laser, [most obviously] maritime because it’s a big platform, but we’re also looking at the land domain, and there are various configurations, both mobile and static.” He explained that the latter had the advantage of being able to be bigger and, as a consequence, higher in power output.

“As for what comes first,” said Cooper, “it depends on where the MoD in London decides its priorities lie.”

“From a systems perspective,” added Wray, “we can see a route to that miniaturisation, or the scaling of [DragonFire’s capabilities] and therefore you can see steps down that path that could be very relevant to different platforms and that staged approach, where a larger platform could be first. And we understand what those steps are, to be able to take from the system that we’ve demonstrated now through to something that will be applicable for early platform activity.”

Wray confirmed that, in terms of interest from the MoD, the areas of focus are predominantly maritime but also land applications. He confirmed that the Royal Navy’s Type 45 destroyer was on a ‘target list’ of applications that the DragonFire team has been asked to consider.

In terms of developing an actual deployable weapon system from the DragonFire demonstrator, the officials noted that, while the DragonFire is effectively a UK-sovereign capability, some components, such as the fibre amplifiers, had been sourced from outside the UK simply because it was cheaper or more expedient to do so. They maintained, however, that they could ‘see a path’ to bringing to production of those components onshore.

The officials also noted that additional work would need to be done to ensure the robustness and reliability required of a deployable military system.

A key advantage of LDEW systems is that they effectively have a ‘bottomless magazine’; as long as they have the required power input, they will never run out of ammunition. They can also be directed to give specific effects, for example by destroying a hostile aircraft’s sensor, without necessarily destroying the whole aircraft itself.

However, the need for LDEW systems to have a certain dwell time to address each individual target might mean than for certain applications – such as swarming attacks by loitering munitions – other technologies might be more effective, such as high-power microwave weapons that can effectively attack a whole sector of airspace at a time.

The UK MoD and armed forces will therefore need to think very carefully about where the most fruitful applications for DragonFire’s capabilities might lie before embarking on developing an actual weapon system.