While the Middle East and Africa are no strangers to the use of drones in warfare, increasingly, many of the technological developments, trends, and tactics in unmanned vehicle employment observed in Ukraine appear to be proliferating.

It was around December 2023 when the first evidence began to appear on social media – a grainy video feed with two propellers just visible at either edge of the screen, with various warnings flashing in white between them. Only this time, the drones providing this video were flying over wide green fields with banks of orange soil and hunting down cars in impoverished towns.[1] First-person view drones (FPV) had made their way to Syria. With the help of Russian advisors, the Syrian regime was striking at opposition forces and their civilian supporters using the same types of small drones that had been prominent in Ukraine for over a year. To some, this might herald the beginning of drone warfare in the Middle East, but the region is no stranger to munitions commercial drones.

ISIS used drones extensively in the battle for Mosul, flying over 300 missions, leading General Raymond Thomas, Head of the US Special Operations Command at the time, to state that ISIS enjoyed tactical superiority in the air over Mosul. At one point in 2016, ISIS deployed over 70 drones in a 24 hour period in Mosul, many of them armed, which almost brought the Iraqi offensive to retake the city to a halt. Maj Gen Roger Noble of the Australian Army was the deputy commanding general of the Combined Joint Forces Land Component Command – Operation Inherent Resolve during 2016; he recounted one company-level attack conducted by ISIS that involved armoured vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs), indirect fire from mortars, bridging equipment, infantry, as well as drones for reconnaissance and command and control, indicating the level of complexity that non-state actors have used drones for.[5]

Then, in January 2018, a wave of drones built from plywood and plastic bags began to emerge in Syria, shortly before a large attack on Russia’s Khmeimim airbase, which the Russians claim to have foiled.[6]

The drones used in these attacks varied in quality and capability, but their use over a decade of warfare indicates that they are here to stay. And now, sub-peer actors throughout the Middle East and Africa have access to them, adding to their ability to fight and counter the traditionally superior firepower of state forces.

Syria

FPV drones were first used in Syria in December 2023, or at least that’s when the first public evidence that they were being used by Assad’s forces became available.[9] By the time their use had made it into major news outlets in February 2024, they had already been used in 13 attacks, often against individuals, civilians and agricultural areas, according to Munir Mustafa, deputy director of the civil emergency group, the White Helmets.[10] The FPVs were manufactured in a lab south of Hama with guidance from Russian and Iranian instructors, as reported to Al Jazeera by Abu Amin who monitors the Syrian and Russian military. At first, it seemed that Assad’s Syrian Arab Army (SAA) were the primary users, but by the end of December 2024, they were also being used by the Syrian Defence Forces (SDF), backed by the US, and the Syrian National Army (SNA), backed by Türkiye. Most notably, perhaps, the Ukrainians also supplied 150 FPV drones and 20 instructors or operators, to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) that were used in its offensive that was ultimately successful in deposing Assad’s regime.[11]

- The tactics and results of FPV drone use are not surprising. There are already videos showing the drones being used against the vulnerable rear turret armour on a T-55.[13] A T-55 turret is made of cast steel with thicknesses between 48 mm and 200 mm; approaching it from the rear with a PG-7 type warhead ensures a very high chance of penetration and behind-armour effects, assuming that the fuzing method used in the FPV drone design works successfully.[14] In other examples, the SDF claims to have conducted a number of strikes against Syrian National Army armoured vehicles, including what appears to be a Cobra II 4×4 armoured vehicle fitted with the Aselsan SERHAT II mortar detection radar. In others, the FPVs are flown into buildings after a reconnaissance drone observes personnel entering the facility. Many SDF videos show the operator emerging from a camouflaged and concrete-reinforced bunker to conduct the mission before returning to cover.

For the SDF and HTS, it seems as though FPV drones provided them with a vital form of precision targeting to counter the traditional firepower of their adversaries, or at least exploited the apparent inability of the Russian and Syrian air forces to interdict HTS’s movements. This has allowed them to pick apart armoured forces of the regime and Turkish-backed groups, which would otherwise pose a real challenge to light infantry forces. FPV drones can also be used against defensive positions to quickly facilitate advances. With the Syrian regime forces defeated and much of the country’s aircraft destroyed on the ground by Israel, it is likely that FPVs will be the only form of precision strike available to HTS’s forces as they work to consolidate their control over the fractured country.

Ansar Allah

Ansar Allah (also commonly referred to as the Houthis) have arguably achieved the greatest success of any non-state actor through using drones, albeit as part of a wider and much more capable arsenal of weapons including anti-ship ballistic missiles. The Houthis differ from other groups covered here in that their drones tend to be used as long-range strike systems rather than tactical assets. Arguably, the uncrewed surface drones used against shipping in the Red Sea are a tactical system, but they are still employed over long distances, making the Houthi inventory more akin to an arsenal of missiles than drones.

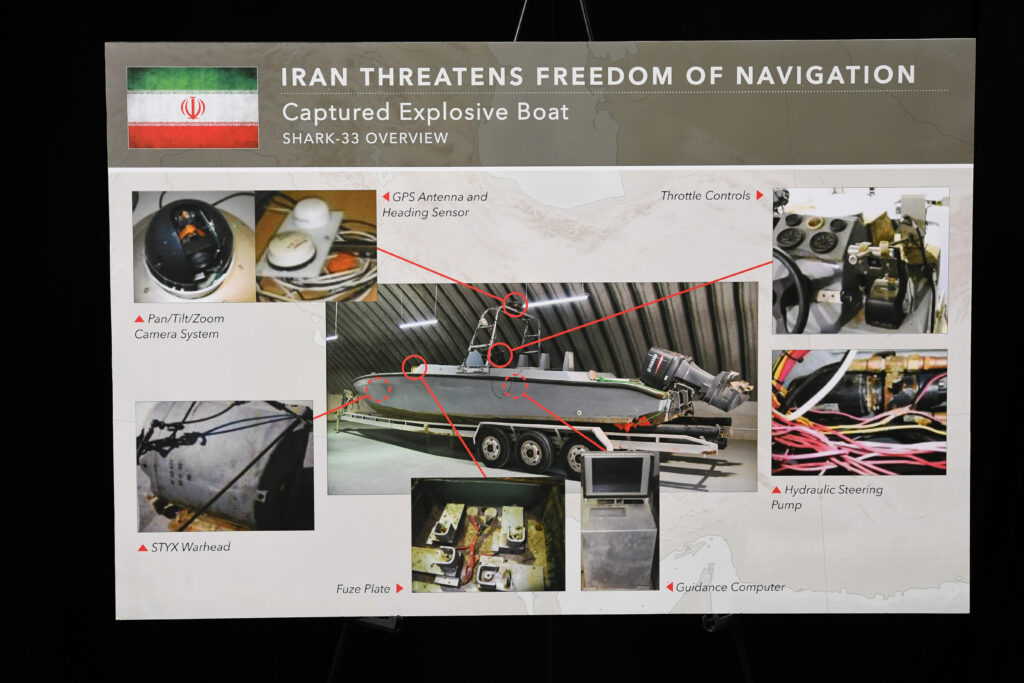

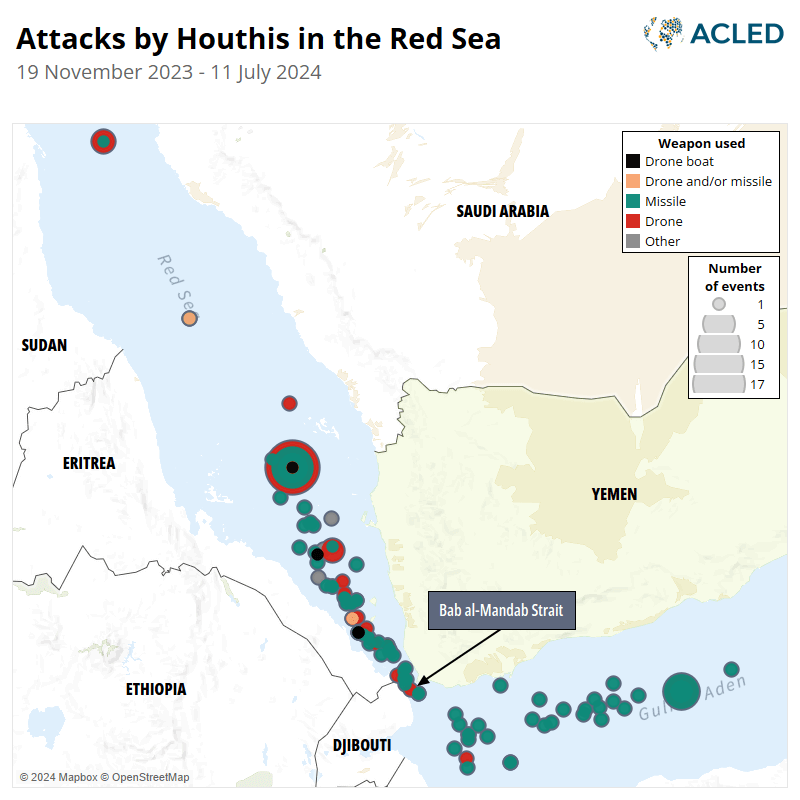

In 2017, the Al–Madinah, a Saudi Navy frigate was reportedly struck by three USVs carrying explosives as it patrolled the Red Sea, leading to the deaths of two crew and injuring three others. At the time, Vice Admiral Kevin Donegan, commander of the US Fifth Fleet and head of US Naval Forces Central Command ominously remarked that he was concerned this new Houthi technology would extend into commercial interdiction and create huge challenges for shipping in the Red Sea and Bab-el-Mandeb straits. Their use of sea drones has expanded significantly, with 25 attempted attacks between July and August 2024, four of them successfully hitting their targets. The Houthi surface drones are believed to be the product of Iranian kits used to convert fishing vessels or fast boats into uncrewed systems carrying an explosive payload weighing up to 500 kg. ACLED data indicates that surface drones are mainly used in the southern Red Sea, which is likely driven by the reduced distances and port infrastructure there.

In the long-range sphere, the Houthis have had the greatest success, including applying strategic effects leading the Saudis and the UAE to seek a compromise and ceasefire in 2022. This has involved the use of Qasef one-way attack drones and Sammad long-range drones for reconnaissance and strikes against critical national infrastructure. The Houthis often combine drones and missiles in a single coordinated strike when they are focused on strategic effect; the 2019 strikes on the Aramco processing facilities which led to a huge but temporary loss of oil output is one such example.

The finite magazine depth of those ships also means that they can quickly be forced back to a friendly base to reload, further exacerbating the costs imposed on a defender.[16] When combined with missiles, drones increase the risk to a defender by complicating the air defence picture; if successful in making it to a target, they can cause significant damage.

Boko Haram/ISWAP

Boko Haram and the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP) operate in the northeastern regions of Nigeria, as well as in Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Mali, and have been known to employ drones in attacks on security forces in the region. The South African Institute for Security Studies (ISS) reports that messaging platforms associated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State are used to share knowledge on the use of drones with partner organisations in Africa.[17] It is also likely that the groups are using their own connections to source and buy the drones that they have used. One ISWAP attack in late December 2024 appeared to employ a DJI Mavic type drone; an 82 mm mortar round was also shown alongside the drone.[18] It is worth noting that an 82 mm mortar bomb weighs around 3.1 kg, which is well in excess of the maximum take-off weight of a DJI Mavic, so it is not clear whether or not the bomb was actually deployed by the drone.[19] The group may have used drones since 2022 for reconnaissance and mortar fire correction, with the adaptation of drones to carry munitions being a natural evolution from that point.

The Mavic is a popular choice for drone operations and is seen more often than the more bulky DJI Phantoms. The Mavic (depending on variant) can fly for up to 43 minutes and transmit 1080p/60 fps HD video footage at ranges up to 15 km, with a maximum flight range of 28 km. Put simply, this means that the video relayed by the drone would be sharp and detailed. The Mavic can also fly at altitudes of 6,000 m, at which height the whine of its four motors would be barely audible. Like many drones operating in this space, it includes automated flight controls that reduce the training burden on the operator and interchangeable batteries, which is another key area for the use of drones in combat. They may be used to fly almost continuous missions, providing no time for recharging batteries. So, swappable battery packs allow operators to keep drones in the air for multiple successive missions. The drone weighs around 900 g, and payload release kits are commercially available for Mavics and other drones, with some users indicating that they can carry their payloads corresponding to their own weight.[20] This payload limitation is what drives the use of the VOG-17/VOG-30 families of 30 mm grenades as drone-dropped munitions. These munitions are designed to be fired from the AGS-17 automatic grenade launcher, and are relatively light, with a VOG-17 weighing around 350 g, which provides enough payload headroom to add an improvised stabilising fin at the rear of the munition.[21]

Mali

In Mali, there is some evidence of Tuareg rebels employing small drones in strikes against the Malian armed forces (FAMa) and Wagner positions in October 2024. Ukraine’s military intelligence appeared to claim some credit for teaching the rebels to operate the drones, especially in the wake of the July attack on a Wagner column that left 84 Wagner and Malian soldiers dead.[24] However, this was later walked back by the country’s foreign ministry after Mali and Niger severed diplomatic ties with Kyiv, citing its decision to arm rebels and terrorists as the reason.[25] The truth of the matter is unclear, however Ukraine is understood to have also coordinated drone attacks on Wagner-backed forces in Sudan, according to a September 2023 CNN report.[26] So, it is reasonable to presume that Ukraine may have provided some support to the Tuareg rebels, but its importance should not be overstated.

Moreover, the Tuareg drones are somewhat outgunned by Mali’s own Bayraktar TB2s, as is also the case for Boko Haram against Nigeria. Mali’s TB2s have been used in frequent strikes against the Tuareg and other groups in the country. Mali is thought to deploy at least 17 TB2s, based on the tail numbers that have been seen in FAMa press releases, however the UCAVs are often delivered in batches of six, which may mean that the true number is 18. The TB2 is obviously a completely different type of strike system to the small hobby drones used by the Tuareg rebels, but Mali’s use of the type and extensive reliance upon them shows how unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in general are spreading and proving their utility, especially in airspace where the threat from ground-based air defence and air-to-air engagements is limited.

Looking ahead

The Middle Eastern and African groups covered here are relatively advanced in their adoption of drones for tactical purposes. The scale of FPV drone use in Syria appears significant from the available evidence on social media, and the tactics and technology used are also similar to that being deployed in Ukraine. They offer a meaningful and available route to cause attrition on armoured forces that are often stationary or exposed by a lack of air cover and electronic warfare (EW). The Houthis have proven themselves to be the most successful in the use of long-range drones for strikes against critical infrastructure and other targets, but this mostly relies upon their ability to combine different weapon types into a single strike and do so at some scale. The capacity to replicate this across other groups is limited and reliant upon assistance.

Regardless of location, counter-drone capabilities will continue to grow in importance for armed forces over the next decade. The response must be layered in many ways; the typical air defence paradigm holds that weapons should be matched to targets and layered according to range. So, ballistic missiles will be targeted by one interceptor and cruise missiles another, with some short-range defences providing a very last line of defence. For drones, however, EW may be one of the most suitable options for its ability to provide wide area coverage – assuming that friendly forces don’t need those frequencies. Yet it is not a robust solution, as regular updates to software in Ukraine have ensured that both sides are able to keep their drones flying and adapt to changes in EW. At the same time, fibre-optic drones that are immune to jamming are beginning to proliferate, and it can be assumed that this technology will spread to other theatres.[29] This means that soft-kill solutions have to be layered with kinetic solutions able to reliably shoot drones down, as well as reverse targeting of the drone operators, and a last line of defence for soldiers on the ground, such as a shotgun with special ammunition designed to defeat FPV drones.[30]

In many ways, this describes a typical approach to air defence with layers and redundancy, and effects matched to threats. However, the drone defence network would, in many cases, have to sit alongside and within the conventional air defence network since so few of its systems are relevant to conventional air threats. This requires specialisation, both in terms of skills and equipment. ISIS, Ansar Allah, and Hamas have all shown what can be achieved with drones against a well-armed conventional force. They have disrupted attacking forces, destroyed defences, and led complex attacks with them. Even factoring in the cost asymmetries of dealing with small drones, the price of not adopting a comprehensive layered approach will arguably be far higher than adopting it.

Sam Cranny-Evans

[1] The Syrian regime is stepping up its use of suicide drones | Syria’s War News | Al Jazeera

[2] Off the Shelf: The Violent Nonstate Actor Drone Threat

[3] Libyan Rebels Reportedly Used Tiny Canadian Drone – The New York Times

[4] Off the Shelf: The Violent Nonstate Actor Drone Threat

[5] Urban Warfare Project; Fighting ISIS in the City

[6] The Poor Man’s Air Force? Rebel Drones Attack Russia’s Airbase in Syria – bellingcat

[7] Mercer Street: Tanker blast evidence points to Iran, says US

[8] Surviving Crewmembers of Bulker Tutor Recount Ordeal of Houthi Attack

[9] https://x.com/RadarFennec/status/1740512496937824379

[10] The Syrian regime is stepping up its use of suicide drones | Syria’s War News | Al Jazeera

[11] Ukrainian operatives aided Syrian rebels with drones, Washington Post reports | Reuters

[12] Kintex : Round PG-7VT with Hollow Charge Tandem Grenade PG-7Т

[13] https://x.com/QalaatAlMudiq/status/1863627793822617910

[15] Six Houthi drone warfare strategies: How innovation is shifting the regional balance of power

[16] Securing the Red Sea: How Can Houthi Maritime Strikes be Countered? | Royal United Services Institute

[17] Drones as weapons: Africa needs better data to anticipate risk

[18] https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1872330365639234034

[19] https://kintex.bg/product-4-15; https://dji-retail.co.uk/products/dji-mavic-3-pro-dji-rc

[20] https://dji-retail.co.uk/products/dji-mavic-3-pro-dji-rc; DJI Mavic 3 Payload Release – Anyone Can Do Drone Delivery!

[21] 30x29mm VOG-17M HE-SD /High-Explosive/ Grenade – Arcus JSC.

[22] EXCLUSIVE: Boko Haram Terrorists Bomb Nigerian Army Base With Drones In Borno On Christmas Eve, Injure Many Soldiers | Sahara Reporters

[23] Army Acquires 43 Drones, Wings 46 Turkey-Trained Personnel

[24] Ukrainian drones provide support for northern Mali’s rebels

[25] Kyiv denies media reports about supplying drones to Mali rebels

[26] Exclusive: Ukraine’s special services ‘likely’ behind strikes on Wagner-backed forces in Sudan, a Ukrainian military source says | CNN

[27] https://x.com/MonkeyCeeMeDo/status/1842702617178243352

[28] The Islamic State and Drones: Supply, Scale, and Future Threats