While industry forecasts for shipbuilding, and the defence industry more generally, are predicting significant expansion over the next decade, differences of opinion remain on the strategies for achieving such growth and the factors that will influence them.

At the Euronaval 2024 defence exhibition McKinsey & Company launched its industry report titled ‘McKinsey on the Maritime Industry: new perspectives on strategy, operations, and the workforce of the future’, in which the company outlined industry forecasts along with various strategies aimed at optimising and accelerating shipbuilding.

A growing market

The markets forecast segment of McKinsey’s report predicted that naval shipbuilding is due to expand quite significantly in the next nine years, with overall market volume by revenue forecast to increase by around 28% between 2024 and 2033. In terms of growth by region, North America is forecast to retain the largest share of global market volume, albeit with a lower rate of growth than other regions, with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.2%. By contrast, the Asia-Pacific region is forecast to see the greatest growth, with a CAGR of 4%, while Europe comes second with a CAGR of 3.1%. However, it should be noted that McKinsey’s forecast excluded China, Cuba, Iran, Libya, North Korea, and Russia from its dataset, so both global growth and regional disparities are likely to in fact be greater when factoring in the procurement efforts of two of the five largest navies (China and Russia).

The report noted that the largest sub-segment within the surface combatant market was the frigate and corvette segment, and looks set to remain so, forecast to grow by 27% in McKinsey’s report, from EUR 25 billion to EUR 32 billion. Alongside frigates and corvettes, the report noted a high degree of growth in the conventional (non-nuclear) submarine market, forecast to increase by 37% out to 2033, from EUR 7.5 billion to EUR 10.3 billion.

During Euronaval, ESD got the chance to interview Benjamin Plum, Associate Partner at McKinsey and contributor to its maritime industry report. Beyond the aforementioned growth trends, Plum pointed to the nuclear submarine segment as another where production is set to increase: “I would anticipate that nuclear submarine production will increase as well…the US Navy has stated that they want a ‘two plus one’ construction cadence, (two Virginia-class submarines plus one Columbia class). That represents a significant increase over current production rates [as] the United States is currently producing about one Virginia class per year. Additionally, given the scale of the Columbia programme, that alone is also a significant increase.”

Credit: Crown Copyright 2023

Plum pointed to the trilateral AUKUS agreement between Australia, the UK, and the US as being a key driver of growth in the nuclear submarine segment. Under current plans, Australia plans to acquire three Virginia-class submarines with the option for a further two, as an intermediate capability, entering service in the early 2030s. This is due to be followed by Australia and the UK jointly producing a future submarine design dubbed ‘SSN-AUKUS’, based on a modified version of the design envisioned for the UK’s SSN(R) programme. Deliveries are expected to begin taking place in the late 2030s for the UK, and early 2040s for Australia.

Accelerating production

McKinsey’s report argued that meeting the forecast demand increase “presents global military shipbuilders with an opportunity to seek ways to efficiently and effectively meet customer demand”. At the state and procurement strategy level, McKinsey advocated joint procurement as a means of leveraging economies of scale to lower unit costs. At the industrial level the report called for an expansion of modern best practice methods to decrease costs and improve efficiency, including modular construction techniques, vertical integration, employing a digital operating model to manage shipbuilding processes, use of digital twins for design and upgrades, along with greater automation.

Aside from these, one of the more notable operational changes for shipbuilders advocated by McKinsey’s report was for manufacturers to move from process-focused operations to product-focused operations. As the report explains, process-focused operations are the more traditional model, in which “people, equipment, and other assets are consolidated based on the tasks that they perform”. An example of this would be a welding team, who might be assigned to work on hulls, control surfaces, internal structures, or various other components.

By contrast, “In product-focused operations, overall end-product throughput is prioritised over traditional functional area performance metrics. Employees are assigned to a dedicated product or product group, working as a single, multi-disciplinary team. Physical assets are similarly allocated, ensuring that work in process (WIP) does not queue while waiting for shared equipment.”

Regarding the benefits of the product-focused model, Plum elaborated: “What our research suggests … is historically shipbuilders have focused on the process and bringing together a centre of excellence around machining, where the elements would flow through that process-organised manufacturing centre. What we’re saying instead is to look these elements as the product, build your manufacturing operation around that, even if … it requires doubling up on types of equipment and having that equipment be in different locations, whereas historically, we’ve thought about centralising common types of equipment, because you get efficiencies in maintenance and efficiencies in manning.”

Credit: US Navy/Branden J. Bourque

While there appear to be production speed improvements to be gained from adopting this approach, in production as in life, major changes seldom come without trade-offs. In this vein, ESD enquired whether or not the more siloed product-focused approach might stymie the proliferation of skills within a particular skills group. To use an example, if a shipyard’s welders were split among various multi-disciplinary product teams, as they would be in Plum’s example of a team dedicated to producing submarine control surfaces, then those welders may lose out on gaining experience with various welding techniques, or experience with welding materials other than those within their specific product group. This in turn could potentially leave said companies more exposed to skills atrophy or loss of specific skills over time due to employee turnover.

Here, Plum answered that “there is a increased amount of cross-training that occurs when you are multi-disciplinary, than when you are specialised. There are ways to ameliorate that effect, and what our research shows, actually, is that by centring on the product, you wind up cross-populating skills in a different way, which is to say, because the teams that are assembling those products are now a little bit tighter-knit, your welders are interacting more, in this example, with your assembly team, because they’re now co-located, learnings are passed, not necessarily just within the trades, but between the trades, we’re actually tracking a number of instances where, when we have people from different disciplines that don’t usually interact start to interact, we can create moments for continuous improvement, or even product or process change that enables one trade to do its job more effectively because of its close contact with the other. Whereas, if the machine shop is physically distinct and in many ways culturally distinct from, let’s say, the assembly area, and the two don’t really intermingle, knowledge between the two is not shared as effectively.”

The wider market – disruptors and prospects for collaboration

Looking beyond production and toward the wider market, ESD asked Plum about his thoughts on the direction of the naval market given the current trend toward ‘collaborative’ uncrewed vehicles, and their attractiveness to navies given the kinds of tactical possibilities they could open up, such as the use of active sonar without the risk of friendly manned vessels being detected in the process. Plum responded, “I’ll agree with you that ‘collaborative’ is the buzzword of the year, at least this year. When you look at the some of the capabilities of unmanned vehicles, both surface and subsurface, and the projected cost to produce those vehicles, it’s pretty exciting. A lot of questions on stable manufacturing have yet to be answered, but they may become cheap enough that, technologies which we might not want to use on manned vehicles – like active sonar – could be effectively deployed to the benefit of crewed vessels”

Credit: US Navy/Electronics Technician 2nd Class Vincent Polito

Going further, ESD asked how this would impact the naval shipbuilding sector, and whether or not it would see newcomers begin to challenge the power of established companies, particularly given the lower barriers to entry in the uncrewed sector, as seen elsewhere in the defence sector with newcomers typically opting to produce either small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or artificial intelligence (AI), or both. Plum responded, “Will the balance of power shift a little bit? Possibly. I think it’s early days for that market, and there’s tremendous incumbent advantage as well, not least of which are capital, connection with the Navy, and deep knowledge of defence tech So there’s massive advantage for incumbents. Disruptors also have significant advantages, – agility being a key, and so I think you’ll see some of the disruptors mature into full-fledged primes themselves. I think you’ll also see some of the disruptors be acquired by heritage primes.”

On the topic of acquisitions, ESD asked whether or not acquisitions of disruptors by ‘primes’ would be likely to be allowed to proceed, given that the US DoD currently appears to be attempting to encourage the formation of new ‘primes’ within the US defence ecosystem, and consequently challenging the present position of the ‘big five’ primes (Lockheed Martin, RTX, Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, and Boeing). Plum responded, “I think that there is certainly an interest in in a broader and more robust set of primes. But that doesn’t preclude existing primes from acquiring startups; I think there’s more than enough opportunity for them to do that, and I don’t expect that they’ll be prohibited from doing so.”

In terms of further potential impacts on the shipbuilding and indeed the wider defence market, there appears to be growing pressure at the European level to change defence spending patterns among member states toward spending on European products. Notably, in the recent European Commission report ‘The future of European competitiveness’, Mario Draghi, serving as the EU rapporteur for competitiveness, noted: “We also do not favour competitive European defence companies. Between mid-2022 and mid-2023, 78% of total procurement spending went to non-EU suppliers, out of which 63% went to the US.”

Credit: USAF/Tech Sgt Nathan Lipscomb

The overall trans-Atlantic defence-industrial relationship is somewhat more complex than Draghi’s report may lead one to assume. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in its November 2024 report ‘Building Defence Capacity in Europe: An Assessment’, directly disputed Draghi’s figures, noting that “[IISS] data indicates that platform procurement contracts signed by European NATO members from February 2022 to September 2024 for selected equipment types amounts to over USD180bn. Of this total, the IISS estimates that at least USD94bn, or 52%, was spent on European systems and USD61bn (or 34%) on US systems, with USD25bn (or 14%) on systems from Brazil, Israel and South Korea… As such, total sales after the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine] in February 2022 are directed more to European manufacturers, with the total going outside Europe amounting to at least USD86bn, or 48%”.

The IISS report also noted that multiple European companies have firmly established themselves within multiple key US programmes, either providing the design basis for key platforms, or supplying key components, adding “The range of European components in US-manufactured defence equipment is increasing, and European-origin firms are growing their physical footprint in the US defence (as well as civil) sector.” As such, Europe’s defence procurement dependence on the US seems somewhat less extensive than characterised in Draghi’s report. Yet this does not necessarily mean that a desire to promote ‘buying European’ is lacking, with Draghi’s report noting “Some EU products and technologies are superior or at least equivalent in quality to those produced by the US, such as main battle tanks, conventional submarines, naval shipyard technology and transport aircraft.”

Against this background, ESD asked Plum about his thoughts on the prospects for future collaboration between the US and European defence sectors. Plum responded, “I think a lot of the challenges facing certainly the maritime industry in both Western Europe and the United States are quite similar. Both face the challenge of the ‘greying workforce, the challenge of attracting new talent, not just to replace that workforce, but actually to enable the manufacturing of future maritime products. We’ll need different talent. Similarly, automation in shipbuilding or the maritime industry is incredibly complicated because of the low volumes and because of the specific, first of/one of class problems that both US and Western European Shipbuilders face. Many of the challenges on both sides of the Atlantic are nearly the same, and I think, therefore, that collaboration would be advantageous.”

Collaboration may indeed be the most beneficial solution to the common problems Plum indicated, but can also be difficult to balance with competing industrial, economic, and political objectives. Draghi’s report should perhaps best be interpreted as signalling high-level interest in a European defence-industrial strategy that would favour increased collaborative procurement, industrial structural consolidation, along with greater spending on European technologies and products. Such a stance seems politically timely, particularly given that across the Atlantic, President-elect Donald Trump has floated the possibility of imposing tariffs on all US imports – a move that would be expected to have significant repercussions for European manufacturers, and may make future trans-Atlantic industrial co-operation more difficult.

Credit: Mark Cazalet

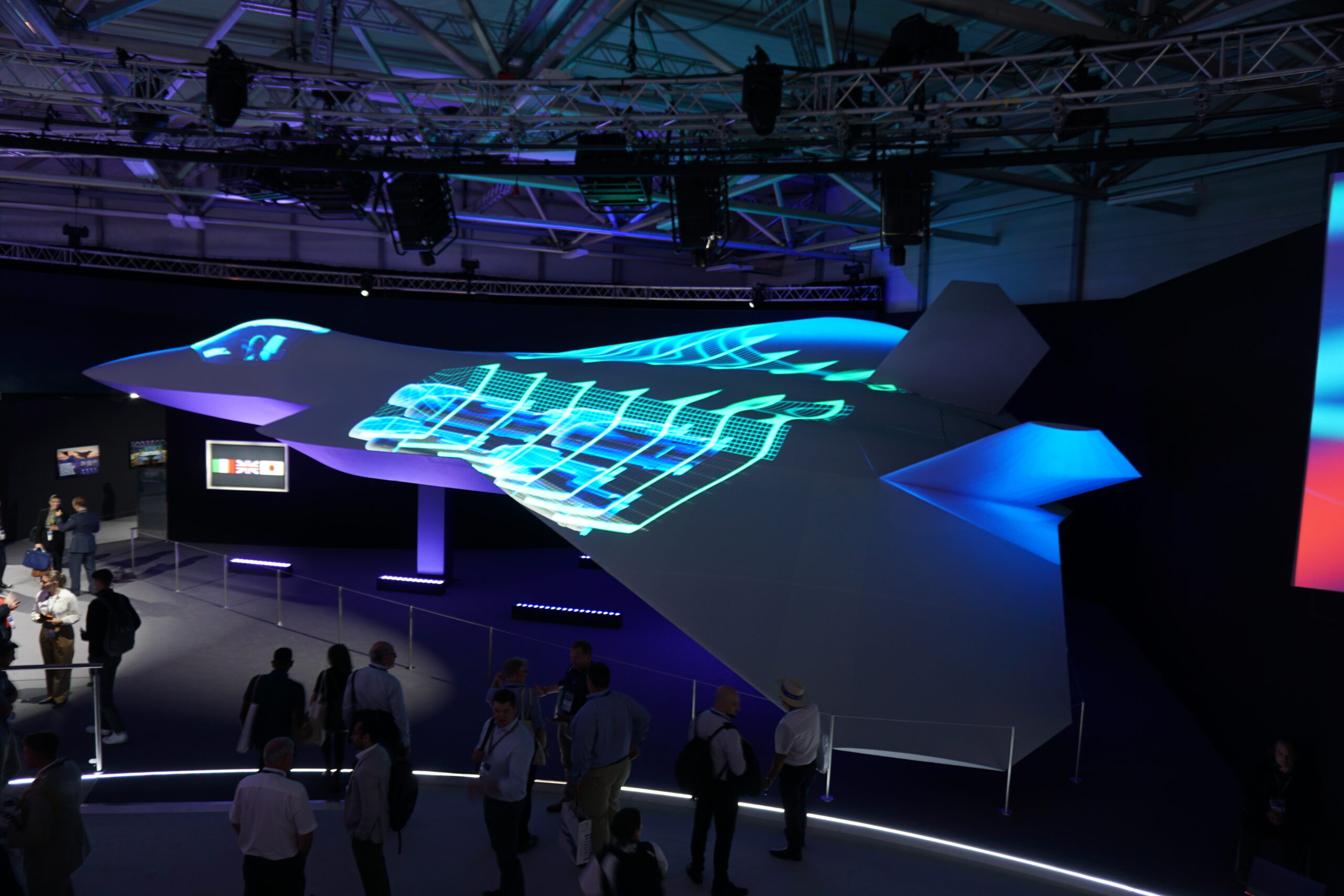

Indeed, if the aerospace sector is to be read as a bellwether, greater trans-Atlantic co-operation may not be where things are headed. In the case of Europe’s two sixth-generation fighter programmes, GCAP (UK, Italy, Japan) and SCAF (France, Germany, Spain), it is noteworthy that neither has sought partnership with US companies. Furthermore, while partnerships between US and European defence manufacturers are not uncommon, they have tended to be unequal, as noted in the IISS report: “full system-level co-operation at peer level among [US and European] prime contractors remains rare. The picture is particularly bleak when it comes to next-generation combat aircraft, where, given the high cost and likely restrictions on technology sharing that would be applied to the export of any US platform, European countries and their defence firms feel a greater imperative to collaborate within Europe. Also, it would be unlikely that they would be able to sell into Washington.”

Many such incentives for intra-European collaboration are unlikely to disappear, and may be supplemented with additional political pressure as European countries navigate relations with a Trump-led US. In many ways, it feels like Europe has been down this road before. French President Emmanuel Macron has long advocated for European ‘strategic autonomy’ to reduce the continent’s reliance on its trans-Atlantic partners. While this message gained some level of traction during the first Trump administration, it largely fell out of vogue since 2021 for two primary reasons. The first was that the election of US President Joe Biden, a trans-Atlanticist, served to soothe fears of an imminent rift between the US and its European allies. The second was that, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, it quickly became apparent that Europe was incapable of adequately responding to Ukraine’s support needs without US leadership in both the political and industrial spheres.

However, much has changed since 2021. The re-election of Donald Trump, coupled with European defence-industrial capacity reforms beginning to bear fruit after nearly three years of war in Ukraine, has meant that European allies may be more receptive to the message of European strategic autonomy this time around. As we’ve seen before, a lot can change in four years.

Mark Cazalet